P/partition: Urvashi Butalia's Volume of Essays in Lower Case

Shruti Devgan reviews Partition: The Long Shadow edited by Urvashi Butalia.

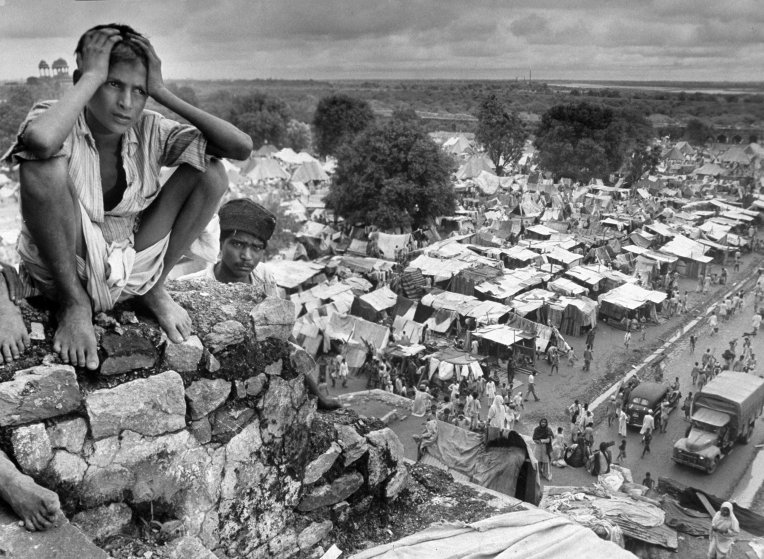

Sikhs migrating to a new homeland after the violent partition of British India in 1947. Credit Margaret Bourke-White/Time Life Pictures, via Getty Images

By Shruti Devgan

Seventy years ago, in 1947, British colonial rule over the Indian subcontinent ended. At the same time, the newly independent subcontinent was suddenly and violently divided by the founding of two new sovereign nation states, one, Hindu-majority India, and the other, Muslim-majority West and East Pakistan (now Pakistan and Bangladesh, respectively). This bloody event is known as the Partition.

The Partition produced one of the largest mass migrations in world history, displacing more than twelve million people and killing at least one million. There were forced conversions, women were abducted, raped, and mutilated; female bodies became sites for the “competitive games of men.” The North West Indian state of Punjab and the East Indian state of Bengal were the most directly affected by the Partition, as their land and populations were arbitrarily and hastily divided and distributed between the new nations. Punjab province was, as historian Yasmin Khan has written, the “most brutally sliced into two parts in 1947…where by far the greatest number of massacres of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims occurred.”

Now, in 2017, the very first physical museum devoted to preserving the Partition’s memories has opened in the Punjabi city of Amritsar. The museum is part of an important moment for reconsidering and reshaping how the Partition is defined and remembered. As the historian Gyanendra Pandey has written, the Partition redefined everyone – Sikh, Muslim, Hindu, and even Christian. Everyone was violently redefined by their religious identity. He writes, “many times since 1947, men, women and children belonging to different castes, classes, occupations, linguistic and cultural backgrounds—have been seen in terms of little but their Sikh-ness, their Muslim-ness or their Hindu-ness.”

Yet, as Pandey explains, nationalist Indian historiography continues to separate “Partition,” a constitutional, agreed-upon division of land and assets from the violence which produced the moment and which was provoked by it. As a result, the violence of the Partition is not often included in its official history. Historians have focused instead on the nationalist, anti-colonial movement that led to independence; when they write about the Partition, they treat it as a culmination of political, economic, and social causes, rather than as an event with ongoing repercussions. Pandey explains, “It is neither the genocidal murder and suffering, nor the issue of consequences for Indian and Pakistani nationalism and nation-building, that provides the charge in this body of writings, but the question of India’s unity.”

Given this record of misrepresentation, the Partition museum signals a shift in the public discourse. It is a way to start making the ghosts of the Partition visible, an important step in facing and memorializing the brutal consequences of the Partition still with us today. The museum is housed in Amritsar’s Town Hall, a building that stood witness to several critical events in the freedom struggle against British colonial rule. Through donations and contributions from public and private sources, the Partition Museum has accumulated a collection of letters, refugees’ belongings, oral histories, photographs, audio-recordings of songs and poems from the pre-Partition era, official documents, maps, and rare newspaper clippings relating to the event. Together the memorabilia reconstruct and preserve stories of the Partition.

Yet, even the use of the term “Partition” remains, itself, fraught. For example, as it was a moment of separation, division, and violence, it was also the moment of Pakistan’s independence, making its meaning both painful and proud for many people.

Furthermore, the singular nature of the term is also problem; the Partition was not the drawing of a single line, it was the drawing of many lines in many places, lines that continue to create and reinforce fractures between and within communities. That is to say, the Partition was not a Partition, it was many partitions.

Indian feminist and publisher Urvashi Butalia’s new edited book, Partition: The Long Shadow , is one of the first works to introduce us to the multiple other, plural, narratives and to explore the durable effects of the Partition. For Butalia, Partition is an umbrella term subsuming many neglected histories within it.

A boy in a Delhi refugee camp; from the new edition of “Train to Pakistan.” Photograph by Margaret Bourke-White / LIFE Picture Collection / Getty

Urvashi Butalia is among the foremost scholars of the Partition. Her book published in 2000, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India, was written with a “deep and abiding feminism” and broke ground in moving from a generalized, sanitized history of events to particular, unheard, and unspoken memories. The newly published Partition: The Long Shadow continues to advance her feminist methodology and study of 1947 by approaching history through personal narrative. Feminist scholars have long rejected the distinction between the political and personal, challenging the impersonal objectivity of interviews, all the while reflecting on the ethical problem of personal narrative. Butalia acknowledges that the essays in her new book are a “small fraction of the many unexplored histories…(only) some aspects of the Indian experience.” Especially because transnational and collaborative research is extremely difficult due to continued hostility and strained relationships between present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Nevertheless, they are an essential new collection of voices and perspectives.

Each of the twelve essays in Butalia’s book has a distinct focus, yet together they tell stories of partitions, plural and in lowercase ‘p.’ The volume includes essays about the impact of the Partition on “peripheral” Indian states such as Ladakh and Assam. The book is also notable for paying attention to differentiation and stratification along caste and class lines within the refugee experience. One of the essays in the book is a poignant account of untouchable and poor refugees’ eviction from Marichjhapi, West Bengal and their mass massacre at the behest of the Left Front government. In keeping with remembering “forgotten history,” the book has an essay about the rise and demise of a pre-insurgency communist militia in Kashmir that fought against princely rule and defended a secular democratic state. The volume also has two essays telling the untold stories of the Sindhi community. Underlying all these essays are broader questions of borders, boundaries, home, belonging, and intergenerational hauntings. The volume’s authors ponder questions of representation and incorporate art and new forms of narrative to tell stories within the story of the Partition.

The best essays in the book contain visual and textual narratives, while others fail to draw a connection with the reader, and remain impersonal and staid chronologies and appraisals of existing representations of the events. The many details specific to each context, and thus each chapter in the book, are a source of rich information but also form labyrinths of people, places, and events that may be hard to navigate for unfamiliar audiences. Yet, this is a much-needed anthology bringing together academics, activists, and artists who often make connections between the personal and political in telling the stories of partitions.

One especially strong essay is by Siddiq Wahid, an academic and political activist, who, in writing about Ladakh, situates the Partition and its effects within the larger phenomenon of modernity. He argues that the Partition forced younger generations of Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians to confront a sudden and rapid change in their established way of life, including a loss of their traditional vocations. Fluid trade routes closed as modern states with strict boundaries, India and Pakistan, emerged, and China took over Tibet, sealing off access to another important trade route. Wahid borrows from sociologist Anthony Giddens to explain the ways in which Ladakhis began experiencing the “discontinuities of modernity” in the early 19th century culminating in the process of decolonization when transition occurred at a speed and suddenness that was “alienating, insidious, imperceptible and traumatic.” Contrary to popular belief that “peripheral” regions such as Ladakh were not affected by the Partition in the same way as “central” states, Wahid argues the “series of partitions—exiles, both physical and mental” are in some ways of greater intensity in the former because they remain obscured.

Similarly, Sanjib Baruah, a professor of political studies, writes in his essay that in Assam, the “meaning of partition has been unfolding slowly over decades through a torturous process.” The citizenship status of cross-border migrants from Bangladesh to Assam is a living issue. Baruah contextualizes this subject and traces its roots to colonial rule. British colonizers encouraged Muslim peasants from East Bengal to migrate to Assam for mostly economic reasons. Resistance to this migration started fomenting in the final years of colonial rule and the Partition exaggerated ambiguities of citizenship and belonging: are the migrants “citizens,” “refugees,” or “foreigners”? In 1947, the Muslim majority district of Sylhet, which was part of Assam, became part of East Pakistan/Bangladesh. The migration of Hindus from Sylhet to parts of the Indian North-East, particularly Assam, is remembered differently than the history of Muslim migration. The continued presence of unauthorized Muslim migrants from what became Bangladesh continues to be a source of tensions. Baruah calls for a partnership with Bangladesh and recommends “instead of trying to harden the border with stricter policing,” the two nations “accept the realities of a soft border.”

The historic 19th-century Town Hall building now home to The Partition Museum in Amritsar.

Photo: Anshika Varma

Kavita Panjabi, a humanities professor, makes the same call for mutual dialogue in a particularly engaging and evocative essay of the book. She reflects on the question of multiple and conflicting identities and belongings through her father’s homeland, Shikarpur in Sindh. In the book’s other essay on the Sindhi community, Rita Kothari, a writer, translator and academic, explains that “unlike Bengal and Punjab, Sindh was not ‘partitioned,’ rather its Hindu minority…fled to India.” Panjabi’s father was one of those who fled from Pakistan to India and settled in Bombay. She writes of his schizophrenic identity, vehemently refusing a Pakistani identity, yet tied to his homeland, Sindh, alongside his passionate political loyalty to the Indian nation. She describes the ways his different identities found a way to coexist: “Within him, his lived realities of Shikarpur and Bombay dovetailed into each other; outside, they were positioned on opposing sides of this geometry of borders.”

Panjabi has written about the loss experienced by the second generation, calling them “postmemories,” or memories of the “generation after” of survivors who experienced trauma (a focus of another essay in the book by Sukeshi Kamra). Even though comparisons between the Partition and the Jewish Holocaust are often made, and to some extent justified, Panjabi draws a distinction between the two. The Partition was not the one-sided genocide of one race by another. It was “an event of reciprocal violence, of a deeply ironic ‘equality’ in which the violated was also the violator, the oppressor also the victim.” Panjabi wonders if the violators and violated nations have the courage and will to mutually acknowledge culpability, mourn together for lost lives, and start looking for mutual forgiveness. She asks if the experience of belonging to homelands can move beyond territorial ownership and if it is possible to claim belonging without possessing?

Partition: The Long Shadow extends Butalia’s project, The Other Side of Silence, which remains pivotal in disrupting official histories of the event. The Long Shadow further complicates these narratives, and reveals fractures within them, by including stories of other communities, caste, class and places and through new forms of visual narratives. The book focuses on many ‘partitions’ in order to dig deep and reach another layer in the multi-layered exploration of memory. As Butalia herself writes:

One cannot begin to open up memory and reach a point where the exercise can be done and laid to rest. Every historical moment that offers us the possibility of looking at it through the prism of memory demonstrates that the more you search, the more there is that opens up.

***

Shruti Devgan is Visiting Assistant Professor of Sociology at Bowdoin College. She received her Ph.D. in Sociology from Rutgers University in 2015, and studies stories of trauma, collective memory, emotions, media and transnational flows with a focus on the Sikh diaspora and India. Her recent scholarship examines diasporic, intergenerational and digitally mediated narratives of state-sponsored anti-Sikh violence of 1984 in India.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.