Postapocalyptic Communities: Tribal and Religious Organizations Respond to COVID-19

How have groups that survived near-genocide reacted to the pandemic and what can they teach us about how to get through this crisis?

Photograph from Sogorea Te’ Land Trust. (Main article illustration on homepage by Inés Ixierda.)

As frightening as it has been to live through the COVID-19 outbreak, some communities have already experienced the end of their world and survived. Indigenous journalist Julian Brave NoiseCat (Secwepemc/St’at’imc) uses the term “postapocalyptic Indigenous people” to describe Indigenous peoples as survivors of genocide. We can extend this framework to survivors of other catastrophes, like the transatlantic slave trade and the Holocaust, making Black and Jewish peoples postapocalyptic, too. NoiseCat suggests “that those who know what it means to lose our world and live might have something to lend to a broader humanity that now faces its own existential crises in the form of disease and climate change.”

As a scholar of religion, I am not surprised that many people have drawn on religion to navigate this challenging time, just as others did in earlier crises. Queer Afro-Caribbean feminist M. Jacqui Alexander argues that religious practices were essential for Africans to survive the horrors of the Middle Passage. When enslaved Africans arrived in new lands, their religions allowed them to make sense of their worlds. This radical transformation also generated new religious forms like Lucumí (Santería) in Cuba and Candomblé in Brazil. Embedded in these practices were traditional teachings and veneration of ancestral spirits, which have remained important for many in the African diaspora.

Today, COVID-19 has radically transformed cultural and religious practices. Some religious groups have opposed coronavirus restrictions. Others have found new ways to engage the community, including streaming Durga Puja, cyber Neo-Pagan Solstice rituals, and social distance powwows. New religious forms have also emerged as the virus disproportionally impacts Native American, Black, and Latinx communities.

I noticed many of these patterns as part of a research team for the COVID-19 Relief and Restoration Work sponsored by the Center for the Study of Religion and the City at Morgan State University with support from the Henry Luce Foundation’s COVID-19 emergency grants. In addition to distributing funds to community organizations, we interviewed community leaders to understand how the coronavirus impacts their communities. I was particularly struck by the central role traditional teachings played in responses to the pandemic by some “postapocalyptic” communities. As survivors of previous crises, they offer all of us important models on how to navigate this challenging time.

Humunya Tribal Foundation of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band

The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band is a tribal government comprised of Indigenous peoples whose ancestors were taken to Mission San Juan Bautista and Mission Santa Cruz in California. They are part of a larger group of tribes often called Ohlone whose homelands are near the San Francisco and Monterey Bays. The approximately 800 tribal members are survivors of three waves of apocalypse, including Spanish Catholic missions, Mexican settlement, and American colonization of their territory. The tribe does not have federal recognition, which means it is ineligible for tribal relief funds from the U.S. government.

Despite not having federal status, the tribe has engaged in various forms of cultural and political revitalization. “We’ve done everything from our language restoration, to bringing back our dance, our songs. All of that takes a tremendous amount of work, a lot, a lot of hours,” said a representative from the Humunya Tribal Foundation. Surviving colonialism has taught the Amah Mutsun the importance maintaining cultural traditions for their tribe to survive into the future. As an outreach organization for the tribe, the Humunya Tribal Foundation has organized educational workshops, tribal wellness meetings, ceremonies, and social gatherings for Amah Mutsun members.

Despite not having federal status, the tribe has engaged in various forms of cultural and political revitalization. “We’ve done everything from our language restoration, to bringing back our dance, our songs. All of that takes a tremendous amount of work, a lot, a lot of hours,” said a representative from the Humunya Tribal Foundation. Surviving colonialism has taught the Amah Mutsun the importance maintaining cultural traditions for their tribe to survive into the future. As an outreach organization for the tribe, the Humunya Tribal Foundation has organized educational workshops, tribal wellness meetings, ceremonies, and social gatherings for Amah Mutsun members.

COVID-19 changed much of this. As the organization’s representative put it, “When COVID hit, we knew that this was going to be really detrimental to our people, and we knew that with unemployment and that, we were going to have to do something . . . We’ve been in charge of the committee and it’s been very eye-opening, just how great our need is.” The organization set up a GoFundMe page for tribal members to help with the cost of food, rent assistance, medical care, and other needs in the wake of the pandemic. Funds have been distributed on a rolling basis, though some members have been granted emergency funds when households have become infected. The organization has also made use of Instacart for contactless groceries, set up a Facebook group with social services resources, and worked with members directly to apply for unemployment.

Because the tribe does not have federal recognition, all relief efforts are grassroots. They report on their GoFundMe page: “Because we are not a federally recognized tribe, we receive no medical, educational, social services or elder care assistance from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Many of our approximately 800 tribal members live paycheck to paycheck and do not have health insurance.” The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, a neighboring tribe, has also set up a GoFundMe page for their own tribal members.

Photo by Protect Juristac of Amah Mutsun Youth Walk for Juristac.

Amah Mutsun has relied on Zoom to stay connected for their tribal council and monthly wellness meetings. Ceremonies have been a different situation. “That’s really tough because so much a part of ceremony is dance, and the fire, and music through our instruments. I mean, there’s no way to hold a roundhouse Zoom, or anything like that,” said a Humunya Tribal Foundation representative. Other Native communities have decided to halt religious gatherings, aware of the ways that earlier pandemics have devastated Native peoples. But the tribe is still finding ways to care for their traditional lands, a value they share with other Indigenous peoples. This includes socially distant forms of land management through the Amah Mutsun Land Trust, an organization that helps tribal members relearn Indigenous ecological knowledge. Amah Mutsun also organized a socially-distant youth walk to Juristac, a sacred site for the tribe. This walk was part of a larger effort by tribal members to halt a mining project on the site. Through these efforts, the tribe has been able to maintain cultural values, even during this moment of crisis.

Sogorea Te’ Land Trust

Named after the 2011 spiritual occupation of the Sogorea Te’ burial ground, the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is an urban Indigenous woman-led organization committed to land restoration. Their website explains that the work of Sogorea Te’, “calls on native and non-native peoples to heal and transform the legacies of colonization, genocide, and patriarchy and to do the work our ancestors and future generations are calling us to do.” Co-founded by Corrina Gould (Lisjan Ohlone) and Johnella LaRose (Shoshone Bannock/Carrizo) in 2015, the San Francisco Bay Area organization is an important cultural hub for the local urban Indian community. It is the site for various forms of Indigenous cultural revitalization and Ohlone and intertribal gatherings. Sogorea Te’ also oversees the formal reclamation of ancestral Ohlone lands. Cultural and land reclamation, what the organization refers to as “rematriation,” is funded through a voluntary land tax called “Shuumi,” a Chochenyo Ohlone word for “gift.”

Photo for Sogorea Te’ Land Trust by “@creative_mudafukah”

According to a recent Instagram post, “Since the first shelter in place order, we shifted into gear to make sure our urban Indigenous community would have safe access to nutritional food.” This new initiative is called Horše ‘Amham, “good food” in Chochenyo Ohlone. Through partnerships with local organizations, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is providing fresh food to Native, Black, and Brown low-income families. Staff are also learning how to make medicines, including herbal tinctures and fire cider, a popular apple cider vinegar tonic. The organization hopes to sell these products and gift some to elders. Like Amah Mutsun, members of Sogorea Te’ Land Trust are learning as they go about how to navigate the growing needs of their communities.

Social distancing provides other changes. Sogorea Te’ Land Team Member Nazshonnii Brown said, “We definitely feel limited in being able to do our ceremonies and gatherings. We’re used to inviting people out and working, bringing on volunteers and working with them at all the different sites. A big challenge is not being able to do those same in-person things that allow us to feel more connected to our community.” Two outdoor, socially distant ceremonial fires were lit for community members who have passed. Ceremony has been a central practice connecting Indigenous peoples to one another, the land, and sacred forces—especially during moments of crisis. As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, however, the majority of social connections for Sogorea Te’ have been virtual and dependent on an active social media presence.

Zoom has served as an important tool to maintain connections. This includes a series of virtual panels featuring Indigenous leaders discussing topics related to wellness and protecting Indigenous sacred sites. Their “Women Warriors: Indigenous Women Protecting the Sacred” panel featured Indigenous women activists from California and Hawai’i. During their discussion, they described movements to protect religious sites and how allies can provide support. Among these places is the West Berkeley Shellmound, an ancient burial site threatened by urban development. Even in the wake of COVID-19, Indigenous leaders have continued the work of ensuring the survival of cultural practices and the protection of sacred places. They recognize that accessing sacred lands are essential for Indigenous cultures to continue into the future.

While COVID-19 created new challenges, many issues remain the same for urban Indian communities. As Brown put it, “A lot of these needs are the same before COVID, and I’d say the big ones are having educational tools, like access to tutoring, or homework help, and applications for college. That need has been in the community, and access to fresh and affordable food.” While they await the return of in-person gatherings, Brown anticipates that new initiatives, like food distribution and Zoom programing, will continue even after shelter-in-place requirements are lifted. By disturbing resources and providing digital content, Sogorea Te’ is ensuring that local Indigenous and Black communities will outlive the current catastrophe.

Black Church Food Security Network

On the other side of the country, the Black Church Food Security Network (BCFSN) in Baltimore is addressing food inequities during the pandemic. “The mission of the Black Church Food Security Network is to create community-based food systems anchored by Black churches and in partnership with Black farmers. We aim to create community-based food systems that are led by those who are directly impacted and affected by food inequity,” explained Sha’Von Terrell, Deputy Director of the organization. BCFSN was founded in 2015 after the death of Freddie Grey while in police custody and the Baltimore Uprising that led to the closure of restaurants and retail food outlets. This left Black communities without access to food. Rather than rely on outside aid, BCFSN works within their networks to support Black communities.

BCFSN’s work is inspired by Black religious and Civil Rights leaders. As Terrell described, “We stand on the shoulders of Albert Cleage. We stand on the shoulders of Mother and Father Divine. We stand on the shoulders of Vernon Johns, Fannie Lou Hamer.” They look to leaders who have helped Black people survive earlier crises for insights to survive current struggles. One of BCFSN’s programs, called the Soil to Sanctuary Market, transforms multi-use church spaces into farmer’s markets where Black farmers can sell their produce. This program draws on the model of Vernon Johns, Martin Luther King’s predecessor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, who farmed, preached, and sold produce to the congregation. However, because of the large volume of high-risk community members and the frequency of COVID-19 outbreaks, BCFSN halted in-person farmer’s markets.

Instead, BCFSN launched a new program, “Black Church Supported Agriculture.” The program works like a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). In this case, BCFSN works with Black farmers in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina to secure produce. The produce is then sold to churches that distribute it to their congregations. “In the spirit of equity and agency and sovereignty, we want to make sure that Black farmers have a market where we are continuing the cycle of self-sufficiency with securing and distributing our food to black communities,” Terrel noted. This model supports Black farmers and Black communities during the pandemic.

Photo by Black Church Food Security Network

New forms of food distribution have coincided with an increased use of digital technology for BCFSN. This includes a series of videos uploaded to their YouTube channel covering canning, pickling, gardening, and seed saving. Other events have streamed live on their Instagram and Facebook pages. BCFSN also launched their Faith, Food, & Freedom Campaign, which aimed to inspire Black churches to patronize Black farmers, create gardens, and engage in emergency food storage during this pandemic. This campaign included a special series of live-streamed conversations with scholars, activists, and community leaders.

At the end of the Faith, Food, & Freedom campaign, BCFSN streamed a virtual Harvest Party to celebrate the work of farmers who sacrificed tirelessly for the community to survive in these uncertain times. Terrell said the aim was, “to create a safe space for people and to acknowledge all of the pain and the loss in the moment, and to also embrace the fact that we are in community with each other. We are not alone at all in this experience.” As communities that have survived the horrors of enslavement, land dispossession, and other crises, BCFSN responds to the pandemic by drawing on cultural teachings to ensure that Black people also survive this apocalypse.

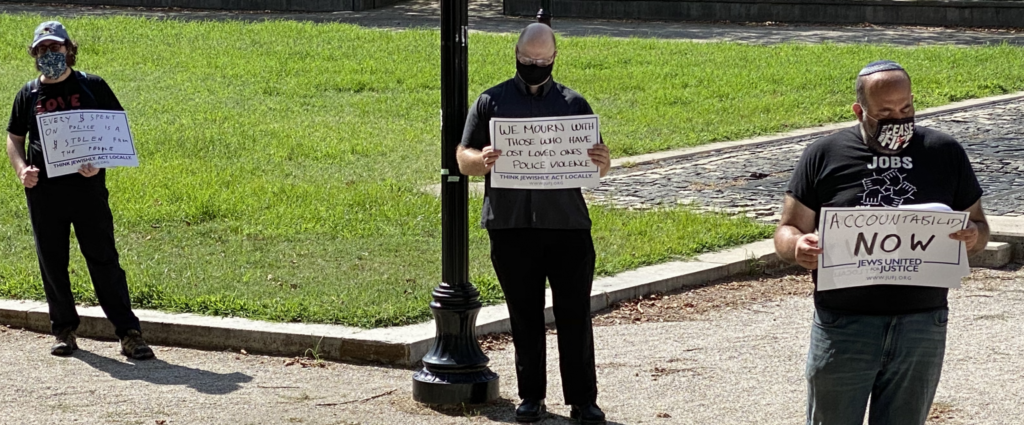

Jews United for Justice

Jews United for Justice (JUFJ), another Baltimore-based organization, has continued its social justice work during the pandemic. “Jews United for Justice advances economic, racial, and social justice in the Baltimore-Washington region by educating and mobilizing our local Jewish communities to action,” according to the organization’s website. Founded in 1998, JUFJ engages in “issue-based campaigns that make real, immediate, and concrete improvements in people’s lives and build the power of working-class and poor communities of color.” Inspired by the work of socially engaged leaders like Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Jewish values like tikkun olam (“the repair of the world”), JUFJ collaborates with organizations to address police reform, renter’s rights, and racial justice.

Some of JUFJ’s political actions fall on Jewish holidays. In 2019, the organization engaged in a protest at the Howard County Detention Center on Tisha B’av, a Jewish day of mourning that traditionally recounts the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. For members of JUFJ, this holiday is also about mourning modern catastrophes. As a group that includes survivors of the Holocaust, JUFJ members ally themselves with others experiencing disaster. The event included readings from the Book of Lamentations, a Tisha B’av service, and acts of civil disobedience. JUFJ’s 2020 Tisha B’av looked different as a result of the pandemic. Several prayer groups were organized in Baltimore around issues of police violence, police accountability, and family separation at immigrant detention centers. For JUFJ organizer Rianna Lloyd, during Tisha B’av “you’re supposed to be kind of like not interacting with people, and so in some ways it actually embodied…the spirit of the holiday even more.”

In other ways, the work of JUFJ has not changed much since the start of the pandemic. Organizers collaborated with coalition partners across the state through virtual mediums even before the COVID-19 outbreak. But the urgency of the issues has changed. One recent campaign was about “freeing people who were in jails, especially those who were at the end of their sentences, who are high-risk, who were there for low offenses, things like that, because we knew that COVID was spreading rapidly and especially in jails,” said Lloyd.

Photo by Jews United for Justice

During the pandemic, JUFJ has also focused on other issues, like housing and water access. JUFJ joined organizations in the Renter’s United Coalition to expand the Baltimore eviction moratorium. Housing is an especially important issue for JUFJ, given the complicated relationship Jews have had with housing, which includes a history of American Jews being denied housing because of antisemitism. As Lloyd put it, “We also couldn’t buy houses. But then we moved, and then we told people of color they couldn’t live there.” This complicated legacy inspires much of the JUFJ’s racial justice initiatives, including their continued work with the Baltimore Right to Water Coalition, which makes water more affordable for Baltimore residents. This is especially important given the urgency of hand washing during the COVID-19 outbreak. These forms of political organizing suggest a continuation of socially engaged Jewish values as active in JUFJ’s response to the pandemic.

Preparing for the Future

Taken together, these stories describe how religion has remained active within “postapocalyptic” community responses to COVID-19. They are also a call to prepare for what may emerge in the future. Sha’Von Terrell put it like this, “I always say that there will be another crisis, because climate change disproportionately affects low-income and Black communities. When there is another crisis, another flood, another tornado, then how can we be prepared to address those needs as they come because other crises will emerge and other crises will happen?” As survivors of genocide, enslavement, and colonialism, these communities draw on traditional teachings to survive yet another time of uncertainty. Following their example may show us how we, too, can survive this moment.

Abel R. Gomez is a Ph.D. candidate in the Religion Department at Syracuse University. His research focuses on sacred sites, ceremony, and decolonization in the context of contemporary Indigenous religions.