Post-Purity Culture: The New Online Frontier of Evangelical Sexual Ethics

Both evangelicals and ex-evangelicals are turning to TikTok and other social media platforms to spread their messages about sex

(Image credit: Michele Constantini/Getty Images)

We passed a plain white sheet of paper around the study hall room. Most of us were fourteen. All of us were girls. The sheet traveled between the hands of my best friend who had two boyfriends at a nearby public school, onto the girl who asked during Bible class if the “M word” (masturbation) was a sin, and then to my own sweaty palms. After a minute or two, we handed it to the guest speaker, a male youth pastor with stiff gel hair and a gummy smile. He lifted his eyes, poised for a heavy message: “This paper represents your purity. Pass it around to any guy who asks for it and this is all you’ll have to offer your husband.” He lifted the now wrinkled sheet above his head like an oracle and crumpled it dramatically. “Nobody wants something dirty,” he finished, shooting the paper wad into the nearest trashcan.

Later that night I described the lesson to my friend in public school, a proud non-virgin. She cringed and said, “It’s creepy the adults care so much.” She was right. The adults at my evangelical school and church cared deeply about our sexuality. They had us write letters to our future husbands. We signed pledges promising our fathers we would stay pure. We wore silver rings to proclaim our virginity. We knew “how far was too far.” We were told our hard work would pay off when we could present our bodies to our husbands, untouched and pure as unused white paper.

Purity Culture Then

“Purity” is a term evangelicals use to describe sexual abstinence until heterosexual marriage. An entire purity culture has developed to instill in adolescents, especially teenage girls, the importance of virginity until marriage. I grew up in that culture: hair curled for Daddy Daughter Dances with a gel pen ready to sign the school-wide abstinence pact. I’ve since outgrown that world, joined the ranks of what’s now known as the ex-evangelical movement, but purity culture rages on—in church basements, in arenas, and most recently, on social media.

Eager to engage in conversations about the implications of purity culture, I watched the 2015 documentary Give Me Sex Jesus. The film opens with a simple prompt: “Talk to me about purity.” Some interviewees laugh. Others blush. One person recalls praying for God to allow him to live long enough to have sex. The film pulls back from personal narratives to explore the origins of evangelical purity culture. Historians, ex-church leaders, and current ministers shed light on how the movement swept the hearts of millions of teenagers at its peak in the 1990s and why it still resonates today.

One particular scholar in the film, Sarah Moslener, captured my attention. She agreed to a phone call the next week. It turned out that Moslener, author of Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence, was just as engaging over the phone. She distilled all of purity culture in one, simple remark: “The whole point of purity culture is patriarchal power.” According to Moslener, regulating evangelicals’ sex lives is about keeping women submissive to their fathers and husbands. She went on saying, “The trick is getting people who don’t benefit from that power [women] to endorse it.” And women, despite it not being to their benefit, have become powerful proponents of purity culture.

The purity movement’s roots stretch back decades. Starting especially in the 1970s, following the rise of feminism and gay rights, white evangelicals became increasingly concerned about adolescents’ sexuality. Moslener says, “You go from the 70s, the whole ‘save the children from the gay people,’ into the pro-life movement, save the babies, so you’re positioning youth and innocence as the thing to be protected.” White evangelical leaders promoted anti-abortion and anti-homosexuality messages not only in their churches, but also publicly and with the help of the politicians they courted. In 1983 Ronald Reagan published his pro-life book Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation. He further demonstrated his support for evangelicals by funding abstinence-only education in public schools. For evangelicals, this relationship with political leaders was crucial because many believed, as Moslener says, “If you’re not protecting those things [like preventing abortion], God will turn his back from the nation.” And by the early 1990s, as the AIDS epidemic ravaged communities across the country, several evangelical leaders believed “sexually pure young people” could transform the nation from one of sin and plague into one of purity and God’s blessings.

In 1993 Richard Ross, a Southern Baptist youth pastor, inspired by “a whisper from God,” founded the True Love Waits Movement with the hope that adolescents could help save the soul of America through their sexual abstinence. Through True Love Waits, teenagers publicly signed pacts at purity rallies and in youth groups. The original pledge read, “Believing that true love waits, I make a commitment to God, myself, my family, those I date, and my future mate to be sexually pure until the day I enter marriage.” The movement inspired young evangelicals, including the Jonas Brothers, Demi Lovato, and Miley Cyrus to sport silver rings as an outward sign of their commitment to sexual abstinence until marriage.

(Image: True Love Waits pledge cards on the National Mall in 1994. Photo courtesy of Baptist Press.)

In 1994 a True Love Waits rally on the National Mall attracted 25,000 evangelical teenagers. They placed 210,000 abstinence pledges that had been signed by teenagers from across the country in the ground in the space between the Capitol Building and the Washington Monument. Purity had become cool. By 2000, thanks to the rise of Christian pop stars, the song “Wait for Me” by Rebecca St. James had become an unofficial purity culture anthem. Almost a decade after Ross’s whisper from God, in 2004, President George W. Bush increased funding for abstinence education that promoted “chastity” and “self-discipline.” In fact, funds attributed to abstinence-only education grew by 465% from the start to the end of his presidency.

Post-Purity Culture

As some of the virginity slogan t-shirt clad teenagers of the late 1990s grew up, the popularity of True Love Waits began to wane. Some of those teens came out as gay and felt isolated from their evangelical communities. Others believed purity culture had corrupted their ability to have healthy understandings of their own sexuality. In the wake of the purity culture movement, a new movement emerged, catalogued with its own hashtag on Twitter for the first time in 2016: ex-evangelicalism.

Ex-evangelicalism is an umbrella term for those who left evangelical churches in favor of other religious communities or who have abandoned religion entirely. After Trump’s election especially, countless people who had been raised in evangelical communities felt a need to proclaim an ex-evangelical identity publicly. Some prominent purity culture proponents like Joshua Harris, author of the canonic purity culture text I Kissed Dating Goodbye, even renounced their Christian faith.

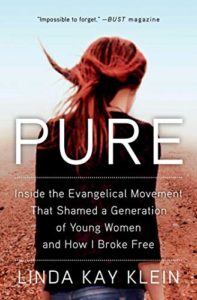

Since the early 2010s, several ex-evangelicals have published personal accounts about the negative impact purity culture has had on their lives. After embracing the label “ex-evangelical,” Brian Chastain started a podcast under the same name, which now receives 13,000 downloads per month. Linda Kay Klein’s memoir Pure, published in 2018, has been the most commercially successful book in the subgenre. In an interview with Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, Klein shared the shame she internalized and explained her own departure from evangelicalism, saying, “When I left, I thought that I was going to be completely free of sexual shame and fear and anxiety. I had so internalized the sexual shaming, that I no longer needed external shamers…I was more than capable of shaming myself.” Her story is similar to ex-evangelicals across the country.

Since the early 2010s, several ex-evangelicals have published personal accounts about the negative impact purity culture has had on their lives. After embracing the label “ex-evangelical,” Brian Chastain started a podcast under the same name, which now receives 13,000 downloads per month. Linda Kay Klein’s memoir Pure, published in 2018, has been the most commercially successful book in the subgenre. In an interview with Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, Klein shared the shame she internalized and explained her own departure from evangelicalism, saying, “When I left, I thought that I was going to be completely free of sexual shame and fear and anxiety. I had so internalized the sexual shaming, that I no longer needed external shamers…I was more than capable of shaming myself.” Her story is similar to ex-evangelicals across the country.

Purity culture’s mass exodus even birthed a school of psychological analysis: deconstruction therapy. In stark contrast to the popularity of “Christian counseling” within evangelical communities, which usually does not draw from peer-reviewed research or require therapists to hold graduate degrees, deconstruction therapy has become a common next step for those who have found themselves with residual trauma from their evangelical upbringing. For some, purity culture left them with feelings of shame and self-hate about their sexual desires. Others report physical manifestations of trauma, including a condition known as vaginismus, a physical tightening of the pelvic floor that can be triggered by a psychological reaction to being taught to withhold sex.

While psychotherapy has been helpful for some ex-evangelicals, others have turned to newer approaches to healing. Allison Tash Montgomery and Hillary McBride have built prominent careers by helping ex-evangelicals overcome feelings of sexual shame. Montgomery is a queer ex-evangelical with a master’s degree in Gender Studies who offers coaching in one-on-one and group settings to help people process their experiences in purity culture and to build healthier sex lives. McBride has a Ph.D. in Psychology and hosts the popular podcast Other People’s Problems to help listeners unpack the sexual teaching they were taught from a young age in evangelical communities and to help them see their sexuality in a positive light.

Podcasts are only one way ex-evangelicals are connecting with one another. There are support groups, new graphic printed t-shirs with the message “Live, Laugh, Lust,” and in person meetups. The hashtag #PurityCulture has nearly 60 million views on TikTok. The hashtag #RecoveringEvangelical has 2.7 million views.

For ex-evangelical Blair Rabun, creator of the TikTok account Talk Purity to Me, the best approach to the trauma of purity culture has been through humor. She films herself candidly responding to media produced by pro-purity culture accounts, fashioning herself as a sort of ex-evangelical critic. Her remarks are snappy, mostly deadpan, and funny. “I think it’s really powerful to be able to laugh at how ridiculous it is,” she said in an interview. And it seems her 20,000 followers would agree.

“I’m more snarky than a lot of people in the community,” Blair went on to explain. Many of her videos are side by side reactions, called duets on TikTok, of conservative Christian videos about purity. Other posts include her own experience, like one where she says, “I had a panic attack the first time I held hands with a guy because I was convinced I had cheated on my future husband. That is a real thing that happened.” At first, Blair’s TikTok account was anonymous, since it’s “kind of a big deal to take on Christianity.” But then she reflected on the impact of personal experience. “At first I was talking about concepts of purity culture, but not about me.” In the future, Blair envisions doing more outreach for Talk Purity to Me by establishing peer support groups and events where people will have space to share their own stories.

Purity Culture Now

Ex-evangelicalism hasn’t eradicated purity culture entirely. Far from it. Purity rings still exist.There are YouTubers intent on sharing the value of waiting for sex, and Instagram-famous couples who broadcast their commitment to virginity until marriage. TikTok has become a mechanism ripe for evangelizing because of its algorithms the facilitate niche communities. And purity culture’s newest defenders have traded handing out Gospel tracts for filming front facing camera confessionals.

There’s Max Milton, a twenty-two year old in Florida with 181,000 TikTok followers. He started creating purity-centric content in 2020 at the beginning of the pandemic. He describes his account as “goofy Christian content” that ranges from a video he plans to show his future wife to mini-sermons on self-worth. “I wanted to show people that pursuing purity was WORTH IT,” he wrote to me. Max runs a Zoom Bible study and calls himself “TikTok’s Big Bro.” In his neon-lit bedroom, promoting purity isn’t a side hustle. It’s his full-time job.

And there’s Emily Elizabeth with 194,000 TikTok followers, whose profile bio reads “Wildly in love with Jesus.” Her content focuses on what she describes as newfound freedom after her earlier life of sexual promiscuity. In TikTok clips, Emily nods as text describing her former life of drinking, taking Plan B, and living with her boyfriend flash across the screen. She looks morose, but confident. She believes redemption is coming. After five years “sex free,” she met an aspiring actor in Los Angeles who shares her sexual values. Her videos look like clips from a romantic comedy and serve as advice for other evangelicals, including why she and her boyfriend avoid napping in the same bed to keep temptation at bay, and how she resists sexual temptation with other people. While the couple waits patiently for marriage, they lip-sync to trending audio in promotion of purity.

Purity culture promoters on TikTok are spreading the same message as those at purity rallies in the 1990s, even as the presentation has evolved. When asked why TikTok over other outreach methods, Milton said, “TikTok isn’t the ideal platform in the sense that this message is the most celebrated, but it is ideal in the sense that is the most NEEDED. Being that TikTok is so fast-paced, it makes sense that it would be especially sexualized. The darker the room, the brighter that your light will shine.” In the dark world of quick sexual encounters, the brighter the purity culture light shines.

***

Purity rings. Pledges. Social media influencers. The virtue of a pure woman. These were the totems of an ideology I witnessed firsthand as a teenager that hinged on my abstaining from sex until marriage. The messages remain the same today for millions of evangelicals who have been told by pastors, parents, and TikTok stars that their self-worth is determined by their sexual choices. But others are coming forward to share their stories, talk about their trauma, and to imagine new sexual ethics. In large numbers, ex-evangelicals are breaking their silence, sharing their pain, and insisting there is a way forward—with each other—online and in-person.

Erika Veurink is a writer living in Brooklyn by way of Iowa. She received her M.F.A. from Bennington College.