Parodying and Using Religion to Try to Save the Planet

A conversation about George González’s book, “The Church of Stop Shopping and Religious Activism”

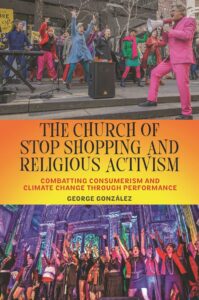

(Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Choir in 2005. Image source: Revbilly.com)

I first encountered Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Church at a protest against the war in Iraq in New York City in early 2003. I had just moved from Vermont to intern at the War Resisters League, a secular pacifist organization. As a newcomer to the city, Reverend Billy, the pompadoured “priest,” and his colorful choir were not much stranger than other things I witnessed on New York City’s streets. But they definitely made an impression. Was he a “real” priest? Was this a “real church”? Who was I to say? My horizons were expanding as fast as George W. Bush was rushing the country into war.

While much time has passed since that first encounter, every few years I have seen Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Church again—at Occupy Wall Street, at Black Lives Matter protests, even once at the opening for an art exhibition—and I have remained curious about them. In the ensuing years, I also got a degree in religious studies and became part of The Revealer, where I got to know George González.

González, an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Baruch College and the CUNY Grad Center, began his field work with the Stop Shopping Church (SSC) in 2016, and spent four years interviewing, observing, and participating in actions with the group. His book, The Church of Stop Shopping and Religious Activism: Combating Consumerism and Climate Change through Performance (NYU Press, 2024), is richly observed, stylish, and incisive. This book and our conversation about it are connected to previous work we have highlighted in The Revealer about the relationship between both scholarship and activism (see my conversations with Laura McTighe and Janet Jakobsen) and religion and capitalism (see my conversations with Rebecca Bartel and Elayne Oliphant). For this conversation, I wanted to chat with González about the Stop Shopping Church’s unique approach to activism and how the group uses religion to broadcast its messages.

Kali Handelman: Let’s start by establishing some background about the Stop Shopping Church (SSC) and how you came to write a book about the group. What first drew you to the SSC, and what questions compelled your research about them?

George González: The Stop Shopping Church (a.k.a. Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping) refer to themselves as a radical performance community of singing activists. They were co-founded by William Talen, an actor and musician who has been performing as Reverend Billy since the 1990s, and Savitri D, a classically trained dancer and choreographer, who directs the group. The two are partners in art, politics, and life and are parents to a young teenage daughter.

In the group’s early days in the early aughts they were known as the Stop Shopping Gospel Choir. Talen’s original vision was to create a parodic Gospel Choir to accompany his anti-consumerist preaching as Reverend Billy. While they gained prominence as a “fake” choir that critiqued consumer capitalism with the flare of religious zeal, over time they developed into something of their own religious community. That is an important thread of the book.

The Stop Shopping Church is based out of New York City although a satellite group formed in the U.K. in 2022. Recruitment generally happens through word of mouth and through the group’s existing activist and artistic networks. At a minimum, active members of the Stop Shopping Choir commit to three Sunday rehearsals a month. Over the years, the group, whose cohort at any given time ranges between twenty-five and thirty active members, has been remarkably multiracial, queer, and multigenerational. They have sung with folks like Joan Baez and have toured with Pussy Riot and Neil Young. They have performed at festivals around the world; been the subject of the nationally released documentary, What Would Jesus Buy; and targeted the corporate practices of Disney, Starbucks, J.P. Morgan, Chase Bank, Walmart, Amazon, and others through street theater, songful protest, and political vaudeville. They have been involved on the ground supporting emerging social movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, as well as the protests in Ferguson and at Standing Rock. While maintaining an anti-consumerism core (one of the first members of the group I met told me she hadn’t used a credit card in ten years), today the community also prioritizes racial justice, queer liberation, justice and sanctuary for immigrants, First Amendment issues, the reclaiming of public space for use as the commons, and, most centrally, climate justice.

The Stop Shopping Church is based out of New York City although a satellite group formed in the U.K. in 2022. Recruitment generally happens through word of mouth and through the group’s existing activist and artistic networks. At a minimum, active members of the Stop Shopping Choir commit to three Sunday rehearsals a month. Over the years, the group, whose cohort at any given time ranges between twenty-five and thirty active members, has been remarkably multiracial, queer, and multigenerational. They have sung with folks like Joan Baez and have toured with Pussy Riot and Neil Young. They have performed at festivals around the world; been the subject of the nationally released documentary, What Would Jesus Buy; and targeted the corporate practices of Disney, Starbucks, J.P. Morgan, Chase Bank, Walmart, Amazon, and others through street theater, songful protest, and political vaudeville. They have been involved on the ground supporting emerging social movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, as well as the protests in Ferguson and at Standing Rock. While maintaining an anti-consumerism core (one of the first members of the group I met told me she hadn’t used a credit card in ten years), today the community also prioritizes racial justice, queer liberation, justice and sanctuary for immigrants, First Amendment issues, the reclaiming of public space for use as the commons, and, most centrally, climate justice.

My interest in the group goes back to the late 1990s, give or take a couple of years. At the time, I was in my mid-20’s and living in NYC. As a young adult, I felt increasing unease about the creep of branding, advertising, and logos into everyday life. I remember having strong feelings that capitalism wanted more from me than I was comfortable giving. For example, in the 1990s, there was a sharp rise in the selling of progressive politics through consumption such as Absolut Vodka’s association with gay causes, a turn that unnerved me as someone who was increasingly interested in and aware of the structural problems and excesses of capitalism. Remember, too, that after 9/11, President Bush and corporate leaders told us that it was our patriotic duty to go shopping. Consumption was explicitly endowed with the obligations of sanctified citizenship. I continued to ponder how capitalism itself functioned as—or at least could be experienced—as religion, whatever that meant to me at the time.

In the book, I argue that, in their own grassroots and performative lingo, the Stop Shoppers have long noted (even before scholars) the co-implications and fusions of religion and economics that ground the cultural logic and authority of neoliberal capitalism. Reverend Billy’s religious drag, one that eventually became second skin, has served as a mirror, reflecting back nominally secular consumer capitalism’s religious appetites and zeal. An early anti-sweatshop action at the dawn of the new millennium had Reverend Billy and members of the Choir process to the flagship Disney Store carrying around large crucified Mickey and Minnie Mouse plush dolls on long sticks to draw attention to Disney’s exploitations.

More generally, though, why dress up as an anti-consumerist preacher, hail fiery sermons of condemnation at the likes of Starbucks and Chase bank, and sing songs about being flooded out of existence? It is to identify capitalism as a religious adversary whose ecological effects are apocalyptic.

I would say that the basic motivations of the book were to investigate why performances of religion became so central to the anti-capitalism of the Church of Stop Shopping to begin with; why religion continued to be the fulcrum that it has been for the group as its work has transformed from its foundational focus on anti-consumerism into a more capacious kind of political ecology; how the group’s relationship with religion has changed over time; and why and how the grassroots activists seem to have beaten most scholars to the punch when it comes to analyzing connections between religion and capitalism.

KH: Why do you think the form and idiom of religion has been so powerful—and challenging—for the Stop Shopping Church?

GG: Understanding the Stop Shopping Church’s powerful but thoroughly anxious attraction to religion is the key to making sense of their diagnoses of both what fundamentally ails society and what might still help turn us away from the abyss. And it is just as central to understanding personal and community tensions that have been there from the start.

It is important to go back to William Talen’s early development of the Reverend Billy character in the 1990s and Savitri D’s fascinating religious biography and childhood growing up in a commune in Taos, New Mexico. To make much longer stories short, Talen speaks openly about how and why he considers the Dutch Calvinist religious world he grew up in traumatic. Originally, the character of Reverend Billy was conceived as a spoof on conservative televangelists like Jimmy Swaggert, the rhetoric of Don Wildmon and the Moral Majority, and celebrity culture—the telegenic performances of Elvis, in particular. The goal was to grind together the two fundamentalisms Talen saw that drove American society: conservative Christian Evangelical Protestantism and celebrified consumerism. I read the parody—its exaggerated delivery, bright white preacher suit with boots for the battle, golden pompadour, fire and brimstone sermons about the evils of Mickey Mouse as the antichrist—as a strategy to bring attention to the religious character and passions of consumer capitalism. At first, Talen was hesitant, in his own words, to “even spoof a Christian” given his background. However, he eventually became so identified with Reverend Billy that even he and Savitri D eventually had to concede that, like it or not, he had in many ways transformed into the persona.

(Rev. Billy in 2011. Image Source: David Shankbone/Wikipedia)

Even though Revered Billy is not an ordained minister, people commonly treat him as such: mothers approach Reverend Billy to bless their children, progressive clergy invite him to join a confab at a rally for immigrant justice, frightened souls look to him for comfort in the immediate aftermath of tragedy.

Savitri D believes religion came upon Reverend Billy following things like 9/11 and the deep pain and suffering of the Great Recession in 2008. Such moments demanded care work that was “sincere” and “direct.” While he first came on the scene as a provocateur who poked fun at the spell capitalism hold over us, today Reverend Billy’s fiery sermons are an expression of the power of the group’s sincere ecological convictions and exhortations to change or be drowned out of existence.

For her part, Savitri D’s parents were Greenwich Village bohemian artists who, she will tell you, were proto-hippies who helped model a countercultural way of life that was later taken up by the Baby Boom generation. In 1967, Savitri D’s father, then known as Stephen Durkee, and her mother, then known as Barbara Durkee, co-founded the Lama Foundation, a New Age spiritual retreat center and intentional community near Taos, New Mexico. But her father eventually switched course, converted to Islam, separated from his wife, and founded a Sufi Islamic community. Savitri D’s mother, who adopted the name Asha Greer, stayed on at the Lama Foundation until she passed away a couple of years ago, and was known for blending hospice work and practices of meditative silence. Among other consequences and effects, Savitri D credits her experiences growing up at her parent’s commune among the Taos Pueblo with teaching her vital lessons about how to care for and sustain the natural world.

Today, Savitri D admits to having an inward-dwelling “spiritual life” but does not often talk about it in public so as not to distract from her activism. Nevertheless, she often grounds the work of the Stop Shopping Church in a respect for “the fabulous Unknown” and “living the question”: that is, the mysteries of life that remain at the limits of human understanding and control.

Life at the Church of Stop Shopping can look a lot like what one sees in a traditionally religious congregation. In addition to meeting for weekly rehearsals of their songs (what they call their “hymnal”), performing at festivals, and engaging in charged moments of political street theater to support their activist causes, the Stop Shoppers take care of one another. In addition to child care, moving assistance, professional networking help, and clothing swaps, I have seen the Choir perform and do service for each other. If a member is in the hospital or laid out low, other members will bring them food and books to read. Savitri D and Reverend Billy have also established a modest emergency fund to assist Choir members with the kinds of dire financial emergencies that can arise so easily living in New York City.

Community life within the Stop Shopping Church presents other messy complications when it comes to religion. Members I interviewed identified themselves as Marxist atheists, “crystal-loving” New Ageists, cultural Jews, recovering Catholics, practicing Episcopalians, and “spiritual but not religious.” Some members want the community to lean further into its religious composition. There are also members who admit to holding personal trauma around their experiences with traditional religion, so much so that the very concept of “religion” can sometimes serve as a “trigger.” During the course of my fieldwork, it became clear to me that there is also always a worry among the group’s leadership that if they come across as too warm on religion, it runs the risk of alienating the old school activists who are the group’s core, most devoted audience.

All that said, the Stop Shoppers are keenly aware of the fact that the catastrophes before us, especially around climate, cannot be resolved by doubling down on scientific reason to the exclusion of art, emotional life, and ritual. The values and commitments that will need to drive the transformations of self and society around climate, the group believes, can only be brought into being ritually, within community, through the cultivation of new habits, and repeated social action in the world. The Stop Shoppers sometimes call themselves a “secular” church in order to signal to audiences who don’t know them yet that they are not a Christian group. If one pays close attention, however, it is clear the Church of Stop Shopping exists between religion and the secular. This is why they sometimes speak of themselves as working toward a “post-religious religious” future wherein a heretofore unknown “Earthy religion” corrects what consumerism has distorted and destroyed.

KH: Can you tell us about what the SSC calls the “Shopacalypse”? What is it, and how does it connect to their stated mission of Earth Justice?

GG: For the group, the Shopocalypse basically refers to the cultural system of consumer capitalism and calls our attention to the intoxicating and ecologically destructive way of life it ritualizes. With the fury of recent hurricanes like Helene and Milton, catastrophic drought in the Sudan, and the forest fires that perpetually threaten the Amazon, the Stop the Shoppers understand that the Shopocalypse is already here. We are living it, and the group is asking us what they take to be the most urgent questions: Do we want to survive it? If so, when will we choose to transform ourselves and our way of life since it is already the case that time has begun to run out? They themselves don’t aspire to enter the halls of institutional power but, rather, see their work as a provocation to reckon, at gut emotional levels, with our entanglements with the natural world. They seek to light the imaginative spark that leads to our personal and then collective transformations.

(What Would Jesus Buy movie poster. Image Source: Warrior Poets, 2007/Wikipedia)

In their estimation, the basic moral move of “Earth Justice,” humanity’s most fundamental liberation project, is to recognize that we are not separate from the natural world and that, as such, saving ourselves and adopting a position of justice for the Earth are actually one and the same thing. The Protestant and Protestant-informed secular assumption that humanity stands apart and above the natural world as its steward (and owner) is a logic that must be overcome. In his sermons, Reverend Billy prophetically hails these truths at his flock of consumers: we are the Category 5 storm threatening our complacent horizons; the ecological effects of our consumption boomerang back at us, bringing together nature, economy, and politics in a dangerous brew.

As a constellation of ideas, the Shopcalypse is also a bridge connecting the group’s early anti-consumerism with their focus today on what they call “Earth Justice and Extinction.” One obvious way this is the case is that they draw the necessary connections between carbon emissions, warming seas, extreme weather, extractive industry and species extinction, consumption, and the plastics that have made a home inside human lungs. Accompanying the transformation of the Choir and of Reverend Billy from their original grounding in parodic performance to today’s eco-sincerity, is a reorganization of categories and separations that we are culturally taught to take for granted: religion, art, politics, economy, and nature. The earlier, more parodic performances (like the ritual crucifixions of the Disney mice) sought to exorcise the demons of consumerism from our bodies. They were designed to make us step away from all the advertising. Today, when the group enters a Chase bank branch with a blue tarp and with it mimes the rhythms of the sea, they are ritually conjuring forth, not away. Their hope is to imaginatively reintroduce an awareness of the natural world back into our bodies and back into the scenes of nominally economic performances that ritualize a disappearance of financial capitalism’s implications with and disastrous effects on ecosystems.

KH: After spending so much time observing and thinking about this group for the past several years, what do you think are some of their most important messages for today?

One very basic take-away is that grassroots activists can be brilliant theorizers, social critics, and organic intellectuals in their own right. The dichotomous idea that academics analyze and activists act is overdrawn from the start.

The almost quarter century legacy of the Church of Stop Shopping offers some important lessons for our moment today. Their primary insistence that consumption is a ritual technology of social control—religion as social control—reminds us that our fun and games are always and already political. The attachments of desire that connect us to Disney, Starbucks, and the cultural narratives of Chase Bank have powerful implications for the fates of global labor, geopolitics, and the environment. The group’s performances have always cut past the smokescreens that divide economics, politics, and entertainment from one another. The cultural form of contemporary neoliberal capitalism is, of course, branding, which represents the economy’s religious subsumption of aesthetics and psychology. The Stop Shoppers have been mapping and outlining the shape of branded “post-secular” capitalism for decades.

Trumpism, for example, represents the branding of the American presidency. While it is important to consider how Christian nationalism and historical and systemic racism and patriarchy have contributed to Trump’s ascendency for a second time to the Presidency, I think the Church of Stop Shopping’s focus on performance is vital to understanding Trump’s iconic power, to allude to religion scholar Kathryn Lofton’s analysis of “consuming religion.” The deep histories of race, gender, and class that we certainly need to analyze and engage are psychically and linguistically refracted through lived experience—which is also how branding works. While political commentary has often focused on “RACE! PATRIARCHY! CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM! CAPITALISM!” in the analysis of Trumpism, the lived meanings of all of these should be analyzed via the well-worn scripts that format our proliferating American cultural industries (for example, the spiritualized mythologies of the heroic, mold-breaking entrepreneur) and our basic human desire to belong, a fundamental need that Reverend Billy sermonizes actually stands behind much of our shopping behavior. We need to avoid too much arch abstraction in our social analysis and, as the Stop Shoppers have always done, engage with power as a sensuous practice—as the religion of everyday life.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor and writing coach based in New York City.

George González is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center and Assistant Professor of Religion and Culture at Baruch College, City University of New York (CUNY). He is the author of Shape-Shifting Capital: Spiritual Management, Critical Theory, and the Ethnographic Project.