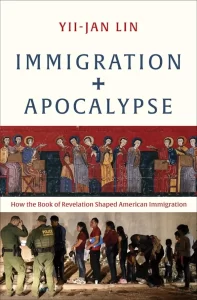

Nothing Unclean Will Enter America, the New Jerusalem

A review of the book, “Immigration and Apocalypse”

(Image source: Current)

Preaching to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1709, the Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather enjoined those gathered before him to transform New England into the righteous city of God, a place blessed by virtue and prosperity. The establishment of such a community in America was, for Mather, God’s will. “Our Glorious lord will have an holy city in america,” he announced, “a City, the Street whereof will be Pure gold.” Drawing on imagery from the book of Revelation, Mather presented a vision of American society that was to become a founding myth of the United States: the myth of America the New Jerusalem, the radiant celestial city in which a God-favored community imbued with exceptional righteousness and wealth would live—but also one that keeps at bay those who do not meet its criteria for inclusion.

Such mythic conceptualizations of American identity are historically commonplace, and they have at times been used to promote inclusivity, as with the image of the United States as a “land of immigrants” where anyone with the will and capacity may achieve prosperity. Yet these myths have often been the basis of exclusion and exploitation. Whether Manifest Destiny—the nineteenth-century belief that the country was destined to expand westward—or the building of largely symbolic walls along the U.S. border, the American myth of exceptionalism has frequently defined belonging in terms of race, and it has demonized outsiders, especially migrants, as less than human.

Yii-Jan Lin, a professor of the New Testament at Yale University, has in her new book Immigration and Apocalypse attempted to trace the outlines of the myth employed by Mather—that of America the New Jerusalem—and how it has shaped conceptions of immigration throughout American history. By examining religious treaties, literature, newspapers, and public discourse from the colonial era to Trump, Lin aims to show that “from the beginning, America has been conceptualized as a prophetic destination and as God’s shining city, the New Jerusalem.”

As a New Testament scholar, Lin is in a unique position to trace the influence of biblical texts on American culture, and how that influence has spilled over into discourse and policy on immigration. Her book can largely be categorized as “interpretation history,” that is, how certain communities have read a given text over time. As she makes clear, however, her goal is hybrid, and she uses Revelation as a lens by which to understand dynamics in U.S. immigration history. In so doing, Lin reveals what may be one of the most pervasive and pernicious themes of American self-understanding: a story we have told about ourselves from the colonies to the present day, a story that all too frequently generated discourse in which people view immigrants as subhuman, disease ridden, and incompatible with American society.

As a New Testament scholar, Lin is in a unique position to trace the influence of biblical texts on American culture, and how that influence has spilled over into discourse and policy on immigration. Her book can largely be categorized as “interpretation history,” that is, how certain communities have read a given text over time. As she makes clear, however, her goal is hybrid, and she uses Revelation as a lens by which to understand dynamics in U.S. immigration history. In so doing, Lin reveals what may be one of the most pervasive and pernicious themes of American self-understanding: a story we have told about ourselves from the colonies to the present day, a story that all too frequently generated discourse in which people view immigrants as subhuman, disease ridden, and incompatible with American society.

The book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse of John, is the last book in the Christian biblical canon. The work belongs to the ancient genre of Jewish apocalyptic literature, which is characterized by a seer imparting visions of the future or of other worlds, frequently accompanied by unusual symbolism. While a great deal of apocalyptic imagery has entered contemporary Western (and especially American) consciousness through Revelation—such as the whore of Babylon and superstitions about the number 666—Lin focuses on the symbol of the New Jerusalem as eminently relevant to American discourse around immigration. She examines other images from the text in relation to this primary symbol, especially the “book of life” and “book of deeds” as determining who does and does not gain admittance to the New Jerusalem.

John’s Apocalypse is full of strange, sometimes grotesque imagery, most of which is allegorical and difficult to interpret. The narrator describes the New Jerusalem only after detailing a spiritual war between the forces of good and evil, the latter portrayed as a series of beasts and a dragon in alliance with “the whore of Babylon.” Plagues, war, and universal destruction culminate in the defeat of the devil and those who serve him. Satan is cast into the lake of fire. God sits upon a throne and opens the “book of deeds” with which to judge the dead according to their actions, and the wicked are likewise thrown into the flames. When God’s victory is complete, the narrator sees a new heaven and a new Earth, and an angel takes him in hand and shows him “the bride, the wife of the Lamb,” which is the “holy city Jerusalem” descending from heaven. It is described as radiant and made of jewels, “clear as crystal,” and filled with the wealth of all nations (21:9–26 NABRE). It is impossibly large, with high walls and twelve gates, and there is no night there, for God’s glory is an ever-present light. The gates are always open, and yet only those written in the “book of life” may gain admittance, and “nothing unclean will enter it, nor anyone who does abominable things or tells lies” (21:27).

The American myth that Lin outlines is structured in accordance with the New Jerusalem as described in Revelation: it is a place for the chosen few, with immense prosperity, and walls and gates protecting its borders. As Lin shows, such apocalyptic conceptualizations of the Americas go back to their discovery by Europeans. For Columbus, the New World was explicitly conceptualized as the new heavens and new Earth, an Edenic land filled with riches that could be used to reconquer Jerusalem. This task, he believed, must be completed before the Second Coming, along with the preaching of the gospel to all the world (which he humbly considered himself to have made possible).

Columbus was not unique among the early arrivals to America. Puritan leaders, such as Cotton Mather and John Davenport, explicitly understood their new communities, and even New England as a whole, as embodying the New Jerusalem. Lin argues that from these colonial beginnings, the myth expanded to encapsulate the entire country, taking root and growing throughout the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, western expansion, and so on, becoming a founding myth of the United States.

To flesh out the way the symbol of the New Jerusalem has operated in the American psyche, ultimately influencing policy, Lin proceeds thematically. She argues that from the colonial period on, the country’s thinking has tended to associate non-white populations with disease and plague (echoing the “uncleanness” of those condemned in Revelation). She then shows how the U.S. government has tended toward the production of vast bureaucracies, creating contradictory and inhumane entry requirements, and violent agencies to systematically manage who can and cannot belong in the United States, all tendencies reflecting Revelation’s process of judgment and admittance to the New Jerusalem.

In the colonies, settlers viewed the Indigenous population’s death by disease as God assisting them to build the New Jerusalem in the New World, while later generations blamed and demonized immigrants for bringing contagion. Religious and governmental leaders, along with many newspapers, especially blamed non-white and non-Protestant migrants for bringing disease. Lin gives examples of discourse and policy that parallel or actively employ rhetoric from John’s Apocalypse, such as an 1883 cartoon depicting a personified cholera in Turkish dress, border agents disinfecting Mexican migrants with Zyklon B, and a newspaper warning against the “uncleanliness” of Filipinos.

It should be no surprise that America as the New Jerusalem is a myth intimately connected with race and power, and Lin argues that from the earliest years of the Republic, white elites wielded immigration laws to maintain racial hierarchies and enforce notions of whiteness as essential to American identity. While the New England colonies largely restricted naturalization to Protestants, in 1790 the U.S. government issued the Naturalization Act, which granted citizenship only to “free white persons” dwelling in the country for two or more years. Yet it was not until the nineteenth century that we find the first general immigration laws, which were concerned especially with Chinese immigrants, on whom Lin spends a considerable time.

Those migrating from China were increasingly singled out as incompatible with “Christian civilization” (as one senator put it). Lin cites congressional speeches, newspaper articles, and political cartoons that imaged such migrants, explicitly and implicitly, as belonging to those excluded from the New Jerusalem, with all the attending sexual corruption, disease, and vice. The Page Act of 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 were implemented to prevent the “hordes” of such semi-human migrants from entering the “Golden Gate” of the New Jerusalem. These acts established the earliest U.S. immigration bureaucracies, with Chinese migrants being held in inhumane locales, such as Angel’s Island in the San Francisco Bay, for weeks or months on end to undergo grueling physical examinations, interrogations, and disinfection. Alongside such laws and bureaucracies arose the idea that certain human beings can be “illegal,” and the history of U.S. immigration since has followed similar lines of racial and ethnic exclusion.

In later chapters, Lin uses Revelation, especially its “book of deeds” and “book of life,” as a lens to understand the increasingly complex network of immigration bureaucracies. Lin argues that historically those placed in the book of life have been primarily white men, while the book of deeds has been used as a means to exclude and exploit those with other identities as convenient for American power structures. Thus, the government placed few restrictions on white, Protestant immigration, while non-whites (frequently including Catholics, such as Italians) had to prove by “deeds” that they belonged. Mexicans or Native Americans, for instance, have been forced to navigate complex systems of bureaucracy and documentation, only to be granted citizenship on the basis of whether the American status quo stood to benefit by it, for instance in the acquisition of land or cheap labor. When the needs of the American elite shift, moreover, the book of deeds can be altered so as to expel or exclude populations that are no longer useful.

Finally, Lin draws numerous parallels between the U.S. border wall and the walls described as surrounding the New Jerusalem. The wall has become symbolic, with politicians such as Steve King and Kiyan Michael comparing U.S. walls and borders to those of “heaven,” clearly referencing Revelation’s celestial city. Much of Trump’s rhetoric of a “big, beautiful wall” further echoes the hyperbole employed in Revelation to describe the city’s walls. Such language, combined with reports, news, and photographs of immigrants at the border, creates a narrative of crisis about the state of immigration. The crisis narrative is used to justify waiving legal safeguards (such as the necessity of search warrants) for those dealing with the “criminals” at the border, or as an excuse for the infliction of violence on immigrants, as with Trump’s family separation policies. The narrative of criminality and fear spirals, frequently creating atmospheres of violence within America, and Lin links immigration discourse to recent rises in white supremacist ideologies and gun ownership among multiple demographics.

(Image source: Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The arguments and historical information Lin presents in Immigration and Apocalypse are compelling and undoubtedly important. Nevertheless, it is fair to question the extent to which one can establish that Revelation is a causal factor in America’s understanding of immigration and its subsequent policies. One could argue, for instance, that Revelation is only one piece of a larger sociocultural heritage, a piece just as much influenced by the prevailing ideas and images of that heritage as causing them. The readings of Revelation employed by the figures Lin examines, moreover, are by no means obvious or necessary, but are themselves shaped by a particular culture, and so the American psyche must have played a role in how Revelation has been read and vice versa.

The book can also feel somewhat unfocused. In the latter chapters especially, Lin concerns herself with drawing parallels between Revelation and U.S. immigration in order to better understand the dynamics of immigration history (as with the application of Revelation’s books to bureaucracies). Lin thus at times abandons the goal of showing how Revelation has shaped immigration discourse and rather uses the biblical text as a lens to understand history. She is honest and explicit when she does this, and both of these tasks are valuable, but they feel like different projects. This, combined with a tendency to jump around between time periods, is at times disorienting, especially given that the text is under two hundred pages.

And yet the work is ultimately coherent. What connects these threads and justifies the project is that Lin succeeds in revealing a prevalent mode of American self-understanding. Immigration and Apocalypse argues convincingly that many Americans, especially those of white, Protestant lineage, have and do conceptualize the United States as an exceptional community, blessed by God with unique virtue and wealth and in need of protection from those who would violate that exceptionalism. In such a view, immigrants are seen as particularly threatening and are frequently dehumanized and abused as a result. The book of Revelation has undoubtedly contributed to this. More importantly, perhaps, Revelation parallels such attitudes, thereby showing them for what they are: basically mythical, unquestioned assumptions. Having shown us the myth of America the New Jerusalem, Yii-Jan Lin has done much to sensitize us to those aspects of immigration discourse and policy that are not based in reason or fact, but in inherited, frequently unconscious patterns of imagination. This is more important now than ever as we grind forward into Trump’s second term, especially given that, as Lin herself has recently argued, Trump employs a great deal of apocalyptic rhetoric.

It must therefore be asked if anything can be done to undermine the myth of America the New Jerusalem and all its attendant cruelties. For her part, Lin believes that “the appropriation of Revelation in immigration discourse must end. . . . The country must forget Revelation, erase it from its national imagination and discourse. What we must do instead is remember history.” While such erasure might be ideal, it is hardly likely, and we would perhaps do better to instead reread both Revelation and America’s place within its symbolism.

Lin’s book is largely about the mainstream discourse of this myth, but she provides examples of other perspectives. Many immigrants have seen America as a golden city of opportunity and inclusivity where all who need help are welcome, and though many were brutally disappointed, their voices can provide a better ideal. Lin herself offers a rereading of the United States, for she points out that while the country devotes resources to military expansion and immigration control, it continues to be a leading contributor to climate change, the disasters of which are poised to be a major cause of migration in coming years, and that “if nothing changes the investment priorities of U.S. political power and money, America will eventually find itself in the lake of fire rather than the New Jerusalem.” If we cannot forget Revelation, we can at least recognize that our walls, bureaucracy, and violence towards migrants do not belong to the order of a “new heavens and Earth,” but to those forces that lead only to suffering and death.

Whether we forget Revelation or simply reread it, it is essential that we refuse the assumption that our current system is somehow inevitable or divinely ordained. By revealing the underpinnings of such assumptions, by tracing the paths, so often contingent and prejudiced, of American mythology, Immigration and Apocalypse teaches us critical discernment to see that “every category, boundary, and law can be questioned.”

Ben Woollard is a writer and editor from Southern Oregon. His work has appeared in Literary Hub, JSTOR Daily, Comment, and elsewhere, and he writes regularly at https://asilkentent.substack.com/.