Not Like Other People: How the Talmud Helps Us Think About People Who Believe They're Above the Law

What does it mean when the rules don’t apply to you?

It was the night after his wife died, and the leader of the Sanhedrin—the rabbinic court— took a bath.

It was the night after his wife died, and the leader of the Sanhedrin—the rabbinic court— took a bath.

His students were puzzled. “Our rabbi,” they asked him, “didn’t you teach us that this is not done? Isn’t a mourner forbidden to bathe?”

The leader of the Sanhedrin told his puzzled students that the rule he had taught them did not apply to him, the Nasi, Rabban Gamaliel.

“I am not like other people,” he said. “I am delicate.”

***

What does it mean when the rules don’t apply to you?

What does it mean to have the power to set the rules? What are the ethical obligations we incur when we have such power? What should we consider when we make exceptions? And how might our ways of engaging the rules thwart—or enable—abusive structures and patterns of behavior?

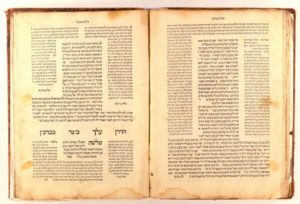

To answer these questions, I am turning to ancient Jewish texts. While the classical rabbis whose voices populate the Talmud were, famously, a self-perpetuating boys’ club with gender politics that leave much to be desired, rabbinic texts can help us think about the dynamics of sexual abuse and assault. How these texts describe power, often in ways that leave feminist readers uneasy, may help elucidate some of our current dynamics behind sexual abuse.

My primary question for now is this: How should we respond when people who create or teach the rules assert that those rules do not apply to them?

***

When Rabban Gamaliel pronounced his uniqueness, his students held their peace—or, so the reader may assume, as that is where the text ends.

His wife, too, held her peace, as she had (again, so the reader may assume) when, years earlier, Rabban Gamaliel had, against his own teaching, taken time out of their wedding night to recite the Shema—the prayer recited every morning and evening, except for extraordinary circumstances, such as a wedding night— and, when his students learned of this, boasted to them of his piety. What say did she have in the rules her husband laid out in the beit midrash—the house of study—which was closed off to her anyway on account of her sex? She might serve to help her husband demonstrate his mastery of the tradition to his students, but neither he nor they would preserve her thoughts, her questions, her experiences. She was, after all, his wife—her name is lost to us—and now she was dead and would hold her peace forevermore.

***

When the rules don’t apply to the one who teaches the rules, who must hold their peace?

It is a core tenet of most feminist analyses of sexual assault that sexual abuse is fundamentally about power, and only secondarily—or, perhaps more precisely, only instrumentally—about sex. To commit sexual assault is to use sex as a weapon through which to exercise power over someone. And it is therefore apt that much recent discourse about sexual abuse has crystalized around the entirely predictable revelation that yet another set of powerful and famous men are, in fact, sexual predators, and that they used sex to control and manipulate people over whom they held professional, social, and economic power.

I am an ethicist who studies Judaism, classical Jewish texts, and sexuality. I’m also a queer, neuroatypical Jewish woman. Power, sexuality, and the ways we communicate and interpret rules are always present in my work. And, as it happens, this core principle about sexual assault as a violent demonstration of power is congruent with what has come to be, for me, a core interpretive tenet: the best texts for thinking about contemporary sexual ethics aren’t necessarily those texts whose subject matter is explicitly sexual. For this reason, I’m drawn to Mishnah Berakhot 2:5-7, a passage from the Talmud that has much to do with power and little to do with sex. In this story, Rabban Gamaliel II—a second-generation nasi, or leader of the Sanhedrin— exempts himself from a series of rules he himself has taught. These stories reveal some of the ways one man relates to his power, and how that affects those over whom he has power.

I am an ethicist who studies Judaism, classical Jewish texts, and sexuality. I’m also a queer, neuroatypical Jewish woman. Power, sexuality, and the ways we communicate and interpret rules are always present in my work. And, as it happens, this core principle about sexual assault as a violent demonstration of power is congruent with what has come to be, for me, a core interpretive tenet: the best texts for thinking about contemporary sexual ethics aren’t necessarily those texts whose subject matter is explicitly sexual. For this reason, I’m drawn to Mishnah Berakhot 2:5-7, a passage from the Talmud that has much to do with power and little to do with sex. In this story, Rabban Gamaliel II—a second-generation nasi, or leader of the Sanhedrin— exempts himself from a series of rules he himself has taught. These stories reveal some of the ways one man relates to his power, and how that affects those over whom he has power.

Rabbinic texts often teach through stories of sages behaving in laudable ways. Sometimes, intentionally or not, they also teach through sages’ bad examples. Now, while the Talmud offers myriad cases of rabbis behaving badly, I don’t think this particular passage means to teach through the sage’s poor example. Indeed, it’s likely that the text approves of Rabban Gamaliel’s behavior. But that doesn’t mean that we, reading now, can’t come at it from a different angle and learn something by evaluating Rabban Gamaliel’s actions with a more skeptical eye.

***

His students were puzzled. “Our rabbi,” they asked him, “didn’t you teach us that this is not done? One does not receive condolences on behalf of slaves.”

The leader of the Sanhedrin told his puzzled students that the rule he had taught them did not apply to him, the Nasi, or to Tavi, his slave.

“Tavi was not like other slaves,” he said. “He was worthy.” (Or perhaps he said, “He was fit,” since the word he actually said, kasher, might be correctly translated as either).

The students held their peace.

Tavi, too, held his peace, as perhaps he had when, years earlier, he had passed by the Nasi’s bedchamber on his wedding night and heard the sound of the Nasi reciting the Shema. And perhaps he saw or heard the Nasi’s wife waiting for her bridegroom.

Was his wife confused? Was she hurt, or frightened? Did she wonder why he did not come to her, that he thought her so insignificant? Was she grateful that she could wait just a little longer before her body became his, or did the wait excite her and make her want him all the more? Was she proud that her husband was so pious? Did she join him in reciting, since if he took on a commandment from which he was exempt, why shouldn’t she as well? And if she did so, how did he respond?

We will never know, since the text doesn’t seem to think her response matters for how the rules are made, and who may break them. It therefore doesn’t tell us what she thought or did. And, thus, neither does the text reveal Tavi’s thoughts or actions. He was, after all, a slave—a worthy slave, but a slave nevertheless—and now he too was dead, and the two—wife and slave–would hold their shared peace forevermore.

***

The passage in question (which I retell in my own words throughout) is a sequence of ma’asot—happenings, or occurrences—in the life of Rabban Gamaliel that appear in the Talmud. In each case, he disregards a rule he has taught his students. Each time, the students ask why. And every time, he responds with a terse and deeply particular explanation.

Here is how the passage reads in direct translation:

A bridegroom is exempt from reciting the Shema on the first night, until the end of Shabbat, if he has not done the deed.

It happened that Rabban Gamaliel recited on the first night he was married. His students said to him: Our Rabbi, didn’t you teach us that a bridegroom is exempt from reciting the Shema on the first night? He said to them: I will not listen to you to remove from myself the kingdom of heaven for even one hour.

He washed on the first night after his wife died. His students said to him: Our Rabbi, didn’t you teach us that a mourner is forbidden to wash? He said to them: I am not like other people; I am delicate.

And when his slave Tavi died, he received condolences for him. His students said to him: Our Rabbi, didn’t you teach us that one does not receive condolences for slaves? He said to them: My slave Tavi was not like other slaves; he was worthy.

None of the specific exemptions Rabban Gamaliel takes are, in themselves, wrong. (I, incidentally, bathed on the first night after each of my parents died). Nor has he technically overstepped his authority to take them. It is, rather, the way the exemptions are made that I find troubling and worthy of exploration.

The key phrase in this sequence is “aini kha’asher kol adam—I am not like other people.” It’s also possible to translate this as “I am not like any other person.”

This second translation is strong and perhaps somewhat forced. But it gets at something important, because it brings into sharp relief the sense that Rabban Gamaliel is exempting himself on the grounds of his particular difference and then leaving it at that. His uniqueness does not, it seems, cause him to wonder about whether there might be other unique persons whose experiences might somehow change how we read or implement the rules. It’s a singular exemption, and one that he’s able to carry out because of his position of power.

This second translation is strong and perhaps somewhat forced. But it gets at something important, because it brings into sharp relief the sense that Rabban Gamaliel is exempting himself on the grounds of his particular difference and then leaving it at that. His uniqueness does not, it seems, cause him to wonder about whether there might be other unique persons whose experiences might somehow change how we read or implement the rules. It’s a singular exemption, and one that he’s able to carry out because of his position of power.

When Rabban Gamaliel uses a variation on the same phrase to explain why his slave, Tavi, merited formal condolences, we see a similar pattern. Tavi was not like other slaves. He was kasher— worthy, or fit. Indeed, other sources report that Tavi was unusually pious. Rabban Gamaliel, therefore, accepted public condolences for him, that his death might be ritually marked. But this doesn’t seem to lead him to conclude that other slaves might also be worthy in important ways. He instead carves out one distinction, because he can, because his slave is not like others.

Even Rabban Gamaliel’s recitation of the Shema when he was exempt from doing so, read back in this fashion, is more complicated. At first glance it seems unlike the other cases: here, rather than taking a leniency for himself, he’s taking an unnecessary stringency upon himself and justifying it on the grounds of his great piety. But it also singles him out as different and less bound to the rules. By beginning with an act of greater stringency, the sequence also functions to indemnify him against later leniencies. (It’s also why I started my own retelling with the second occurrence, which immediately alerts the reader that something is off). Rabban Gamaliel is closer to God, after all, and won’t hear the questions of mere students about it.

***

And as the students of the leader of the Sanhedrin offered him their unusual condolences for Tavi, the worthy, fit, silent slave, perhaps some of them remembered a day several years earlier in the beit midrash—that is, the house of study— when they learned that the Nasi had recited the Shema on his wedding night.

As would come to be something of a habit, when they learned of the Nasi’s deed, they were puzzled. For the tradition, taught to them by none other than the Nasi himself, was that a new bridegroom was exempt from reciting the Shema on his wedding night, until—as the tradition put it, in a way that was at once blunt and euphemistic—“the deed was done.” Deflower first, pray after.

So his puzzled students asked him: “Our rabbi, didn’t you teach us that this needn’t be done? Isn’t a bridegroom exempt?”

He responded with indignant pride, “I will not listen to you, lest I remove myself from the kingdom of heaven for even one hour!”

And the students saw that whatever the reason, it was not up for discussion. Rabban Gamaliel held himself apart from his peers, on account—at least, for this time—of his superior piety. He would always find reasons to justify those ways he diverged from the disciplines he taught others that applied only to him, for he was always cleaving to the kingdom of heaven.

And what of his nameless wife? She—as is the text’s habit where she is concerned—held her peace. Whatever she might have preferred to be done with the story of her wedding night, however she felt, whatever she did, it was no longer hers. She was alive, but she might as well hold her peace now, and the next day, and the next. Her story, as with Tavi’s, as with the stories of so many women like her and slaves like and unlike him, was now her husband’s.

He was, after all, the leader of the Sanhedrin, and he was not like other people.

***

What does this passage teach us about the power dynamics that enable abuse? One mechanism by which power structures can facilitate abuse is when the people in charge of making and enforcing rules make arbitrary judgments about who must comply and who can be exempt—especially if they’re the ones being excused.

We needn’t look too hard to see this dynamic play out in our own context. How do we understand what has happened whenever a prominent male feminist—think Louis CK, for example— turns out to be an abuser? When Eric Schneiderman, the New York State attorney general who built a reputation as a women’s advocate and who filed a lawsuit against Harvey Weinstein, resigned in the face of sexual abuse allegations? When Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, who made unprecedented space for women’s ritual participation, turned out to have been a sexual predator? In all of these cases, I wonder whether the perpetrators decided that they were not, in some crucial way, “like any other person.”

I don’t think this text gives us a clear answer for how to diagnose or proceed. But, if we are to take any lesson from this text, perhaps it is this: when you see a figure who makes rules and exempts themselves from those rules, be suspicious. Maybe it’s benign, maybe it’s idiosyncratic. Maybe they do have particular needs they don’t feel like sharing. But their position of power opens them up to greater suspicion—and, in any case, their lack of transparency has broader implications in and of itself because it builds a climate in which it’s that much more possible for a powerful figure to cloak abuses in the claim that they “aren’t like others.”

And if this is the case with those who claim the feminist mantle, how much more so with someone who does not? This is not hypothetical. When President Trump—a man whom 24 women and counting have accused of sexual assault—was tried in the U.S Senate for obstruction of justice and abuse of power, his defense attorney Alan Dershowitz (who has also been accused of sexual assault) argued that if the President considers his own reelection to be in the national interest, nothing he does to that end is an abuse of his power. In the last gasp of official accountability for a man who, in addition to the actions for which he was impeached, has bragged about sexual assault, shepherded another man accused of multiple sexual assaults to the Supreme Court, and stacked the federal judiciary with people hostile to the self-determination of pregnant and potentially pregnant people, Dershowitz argued that now, at long last, he could not be held accountable. The rules no longer applied to the man whose job it was to carry them out.

He is, after all, the President. And he is not like other people.

Rebecca J. Epstein-Levi is the Mellon Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies at Vanderbilt University. She is an expert on Jewish sexual ethics, and is working on a book on sex, risk, and rabbinic texts. In her copious free time, she enjoys cooking unnecessarily complicated meals and sharpening her overly large collection of kitchen knives.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.