My Father’s Hardest Fight: Assisted Suicide and Hinduism

As one man hopes for physician-assisted death, his family learns about Hindu teachings on suicide

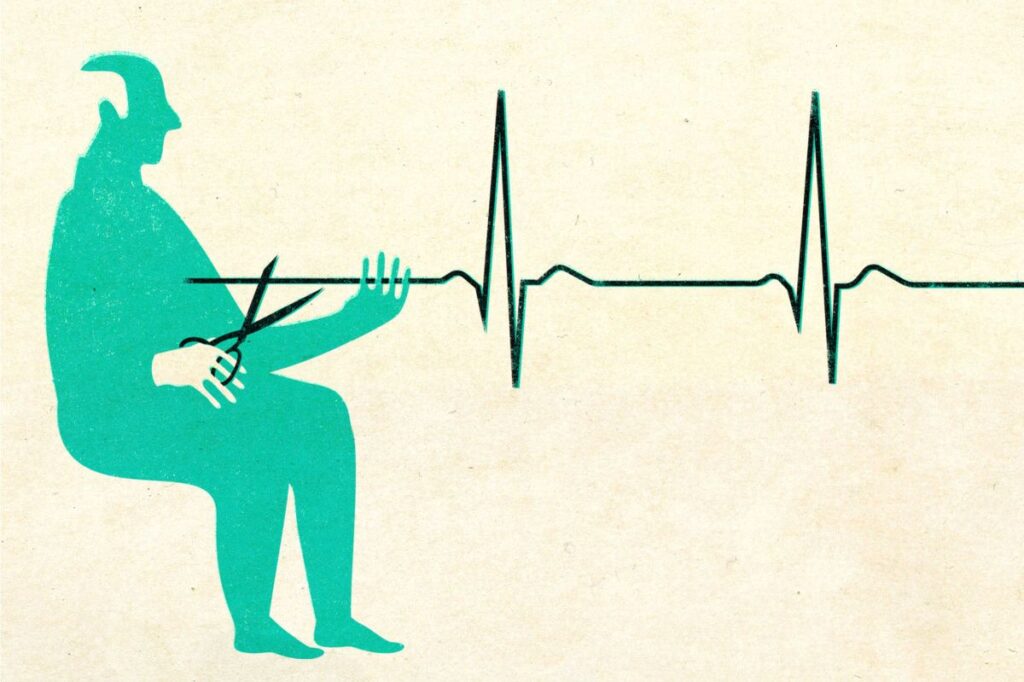

(Image source: André de Loba for UCLA’s Hammer Forum)

“Don’t tell your mother,” my father warned.

“Dad, how can she not know?” I whispered back, a knot of grief forming in my throat.

Both Hindu Brahmins, my parents had an arranged marriage. My mother wore her wedding vermillion on her forehead with pride. She prayed three times a day and could recite the Bhagavad Gita verbatim. She would never approve of what Dad wanted to do.

In April 2022, my 75-year-old dad complained that his right leg was “a bit weak.” A week after Father’s Day in June, it was immobile. On my parents’ wedding anniversary in August, my mother, brother, and I learned that my dad had been diagnosed with Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a terminal neurological disorder that progressively blocks all voluntary muscle movement. The debilitating ailment is commonly associated with scientist Stephen Hawking who lived with it for half a century, though the average prognosis is 3 to 5 years.

The diagnosis was dire enough, but my father’s proposal to deal (or not deal) with it crushed me. He wasn’t interested in a long goodbye. In Canada, where my parents had lived since 2002, “medical assistance in dying” (or “MAID”) is legal. Just a handful of states in the U.S. allow it, but only if death is imminent in six months, as Amy Bloom highlights in her beautiful memoir In Love. She recounts taking her husband, an Alzheimer’s patient, to Switzerland so he could die with dignity.

Dad wanted my help with the paperwork to end his life, without breathing a word to my mother. It wasn’t just because he was worried about her heart breaking. He also knew that she would consider assisted suicide against the Hindu principles of ahimsa or non-violence, and an offense to her religious convictions. My father saw himself as a man of science who wouldn’t be swayed by religious considerations in the face of this inescapable affliction. I was stuck between two stubborn people with very strong opinions.

I’d never paid much mind to my mother’s religious observance. Hindus do not have as many categories for the less-observant among us. While there have been reform movements within Hinduism, there isn’t a Hindu equivalent of Reform Judaism, for example. Like countless others, I was spiritual, not religious, relenting to elaborate rituals in front of shrines only when repeatedly coaxed. I’d participate in festivities and accompany my mother to the temple only if she threatened to get upset. So, it wasn’t religion that made me want to change my dad’s mind. I just wanted him to live for as long as possible.

(Lighting candles for the Hindu festival of Diwali)

On a video call from my apartment in New York, I demonstrated a motorized wheelchair for Dad so that he’d feel like he could be independently mobile.

“I say I should also try bungee jumping!” he glowered as he dragged his walker, flailing till Mom caught him. “Don’t you see? This only gets worse.”

As news of Dad’s condition reached our close-knit Indian community in Toronto, the doom-swirl of horrific patient stories engulfed us: Someone’s aunt couldn’t blink towards the end. Another’s father was bedridden for seven years before his lungs finally collapsed.

Terrified, I called my younger brother, PJ.

“Don’t you at least want to know what living with assisted devices might be like?” PJ asked. “Nowadays there is state-of-the-art everything – wheelchairs, speech aids – you name it. I will find it for you,” my tech geek brother pleaded.

“Can you bring my legs back?” Dad asked, irritated by our insistence.

Dad’s dogged determination formed early in life. Growing up poor in a village in western India, the youngest of seven children, he walked sixteen miles for school in the harsh Indian sun every day. Even with modest means, his mother performed a daily prayer ceremony for her shelves full of gods, convinced that her devotion ensured a better future for her children.

“As a child all I wanted was to have food and shelter for myself and my family,” Dad told us every time we gathered around the dinner table, grateful for what he’d accomplished. He earned an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering and rose through the ranks at a power generation company.

When I came to New York at 20 for graduate school, my parents wanted to be closer to me. They moved from India to suburban Ontario where it was easier to emigrate.

Despite a long, bureaucratic process to get my father’s credentials recognized in North America, he achieved his humble childhood dream for financial security, twice – once in India and again in his new adopted country at age 55. A workaholic, Dad retired from his job with the Canadian government at seventy-four, way past the typical retirement age.

Religious rituals showed up in my life for all the important occasions, even though I rarely lit the customary incense at our home shrine. My husband and I were wedded in a three-hour long ceremony with traditions that came from the Rigveda, an ancient collection of Hindu texts. We separated in 2017 after a ten-year marriage with far less fanfare. I visited my parents often and they helped care for my three-year-old son, Ollie. Dad made Ollie cheese omelets every morning, took him to the park, and jumped into the swimming pool on summer weekends. He dressed in a medieval General’s clothes and held a regal plastic sword guarding Ollie-the-King’s room from “grown-ups.”

My brother and I rushed to our parents’ home in their leafy suburb to care for my dad. We resolved to convince him to live by showering him with care and technological assistance. My Dad had never asked us for help. Leaning too much on even those closest to him was against his values. Now he couldn’t go to the bathroom and wash up without assistance.

As soon as my mother stepped away for errands, Dad pushed me to connect him with a doctor who would assess his eligibility for medically-assisted death. I seethed like an irate teenager, but took some solace that the “Dying with Dignity” website mentioned a wait period of at least ninety days in case the patient had a change of heart. Surely once medical experts learned that it had only been a month since my dad’s diagnosis, they’d advise him to wait before pulling the lethal trigger on his own life.

“Mr. Mukherjee, have you looked into palliative care?” asked the handsome death doctor.

“I don’t want to,” Dad said, angry that this was taking a direction he hadn’t requested.

“I need to know you’ve received all the care you can possibly get before I approve you for the procedure,” the doctor said.

“I can’t go on. Please help me end my agony,” my stoic father begged – not for his life, but for his death.

A date was set for a week later.

“Don’t you recommend that he at least try to live with it?” I nearly shrieked. I didn’t see the point of staying calm anymore.

“He is lucid and very clear about what he wants,” the doctor, who did not appear to be on my side, said calmly.

My father was impatient. “Do you have an earlier date?” My eyes went blurry. Dad had always cared deeply about what the rest of us wanted. Why was he so focused on himself now? Why wouldn’t he give us a chance? He still hadn’t told my mother.

“If Mom finds out I helped you with this, she will never speak to me again,” I said, annoyed that I had to worry about this secret on top of the pain of losing Dad.

The following afternoon, after Mom fed Dad his favorite lunch of eggplant, fish curry, and rice, her cries pierced the walls of our house. “I will not let you go. You have a few more years,” she insisted, regaining her stubborn composure.

“Do you know how hard it is to care for a terminally ill patient? Your health isn’t good either,” my pragmatist father implored.

“I need to speak with Maharaj. He won’t allow it,” she said, her voice shaky, referring to the high priest and her guru at the Vedanta Society of Toronto. Dad struggled to rise from his chair, failed and sat back down. “We’ll fix this,” she said as she rushed to him and sat by his legs on the floor. He raised his weak hand to her head to comfort her.

Determined that a meeting with her guru would change everything, my mother arranged for a visit the very next day. Swami Kripamayananda arrived clad in his saffron robes. He sat opposite my father who was propped up on a living room chair with ample cushions.

“How will your family live without you? You are everything for them,” the Swami said, his face calm, his voice soothing.

“Everyone loses their parents, or partner. It will be hard for them no matter when I die,” my father said, looking Swamiji in the eye. “I will always be there for them,” he continued, turning his face to me.

The Swami was quiet for a moment.

“You sound like ancient Indian monks. They renounced their bodies when it was time to do so without letting worldly attachment get in the way,” the Swami said, filled with awe.

I knew my mother was destroyed inside, but the Swami’s endorsement of Dad’s decision was God’s will for her. I held her hand as she stayed silent, trying to accept her new reality.

My mother was among the Hindu majority in believing that suicide is atma-hatya, or soul murder, and unacceptable. However, as Deepak Sarma, Professor of Indian Religions at Case Western Reserve University notes, Hinduism offers a more nuanced examination of the topic. When one has fulfilled dharma, or their duties on earth, and suffers from an incurable disease at an advanced age, hastening death by giving up eating and drinking, or voluntary euthanasia is permissible. However, committing suicide out of heightened passion, despair, or anger is forbidden. Dad hadn’t factored religion into his chosen path out of this world. And it wasn’t the first thing to cross my mind either. But I welcomed the unexpected comfort that ancient Hindu texts offered.

Two days before his final one with us, a tense and morose silence descended on our home, the kind Dad knew how to break. As the three of us shuffled around him he said, “Hey, do you remember how Puloma played hide-and-seek as a five-year-old? She’d fit into a little corner of the house and say, ‘Dad, I am going to be hiding right here. I want you to look for me all over the house!’” Then he laughed at the memory he’d recounted thousands of times. We did, too.

“Remember that great New Yorker cartoon?”

“Which one, Dad?” I knew which one.

“A guy walks up to a man selling fish on a deserted island where there is literally nothing else and asks – are these fish local?” Dad chuckled loudly. I did too.

“I won’t succumb to this disability. I am lucky,” Dad consoled me on the last evening we spent together. “Remember me as a warrior, who left on his own terms.”

A burnt-orange sunset gleamed through the windows on Dad’s final car ride with my brother and me to the “MAID House,” from where he’d never return. Mom couldn’t bear to come. We helped him on to a chocolate brown reclining chair in a dark room. I held a blessed sunflower to his forehead and chanted “Hare Krishna-Hare Rama,” praying for his soul to go to heaven, as the doctor administered the injection into his arm. Dad’s eyes were closed, head bowed as if in prayer. He looked peaceful.

Five minutes in, somewhere mid-hymn, we heard the doctor say, “I am sorry. He’s gone.”

My brother and I held each other close, like little children. I only endured Dad’s final moments knowing it was how he’d wanted to go.

I began to see the virtue in Dad’s decision. He placed the family’s well-being over his own, as always. Scriptures and judgements aside, leaving behind all that he’d built and everyone he loved was an extraordinary final act of courage and selfless love, values he lived and died by.

Puloma Mukherjee is an immigrant writer and mother based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, Poets & Writers, and in an anthology of short stories. She is currently working on her first novel.