Muppet Religion

On the 30th anniversary of The Muppet Christmas Carol, one writer considers the Muppets’ many spiritual insights

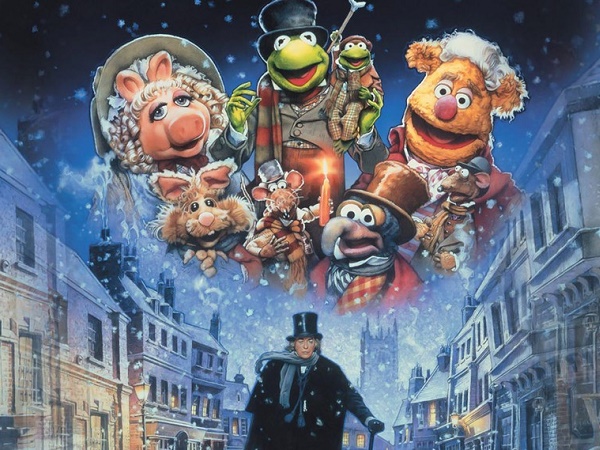

(Image: The Muppet Christmas Carol movie poster)

I am a card-carrying member of the Muppet generation. That is to say: I was reared during the era of Peak Muppet. I was born in 1978. The Muppet Show aired every week during my early childhood, and the Sesame Street Muppets, born in 1969, had truly hit their stride — but had not yet been sullied by The Elmo Takeover.

One of my earliest memories is the CBS “eye” appearing on our living room television just before a drumroll heralded Kermit’s voice declaring, “It’s the Muppet show!” What followed was thirty minutes of the zaniest variety show ever, populated by Muppets and one celebrity human host. The episode where Tony Randall turned Miss Piggy to stone reduced me to night terrors. But the Muppets were also my love language. Ernie and Bert soothed me while my mom applied antiseptic ointment after my first bee sting. Fozzie Bear could always make me laugh. I ate it all up. Creator Jim Henson was just reaching his creative best.

And then abruptly, in my ‘tween years, came the tragedy. On May 16, 1990, Henson died of complications from streptococcal pneumonia. He was only fifty-three years old. I hadn’t fully realized people could just die like that. They broadcast footage from his funeral on the news. I remember seeing bright colors—no darkness for Henson, whose instructions forbade anyone to wear black at his funeral — and delicate butterfly puppets waving among mourners in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. I wept. I was twelve years old.

The Muppets could have ended then.

But they didn’t. Jim Henson’s son, Brian, took on the mantle of continuing his father’s legacy. Two years later, in December 1992, The Muppet Christmas Carol appeared in theaters. Kermit’s voice was different, and it wasn’t a runaway success — but it was enough. It was a Christmas miracle. Three decades later, there have now been more Muppet films without Jim Henson at the helm than with him.

The Muppets, it turned out, were eternal. Whether they are making rainbow connections or excited that there’s only one more sleep ‘till Christmas, Kermit, Miss Piggy, Gonzo and Fozzie Bear all showed us how to believe in our common humanity and the wonder of the everyday. What could be more perfect for we late Gen X-ers — the children of the “spiritual but not religious” Baby Boomers and their marketplace of devotions, desperate for something to counter our cynicism, fearful that we might end up worse off than our parents? The Muppets are our spiritual lingua franca.

***

The most obvious Muppet Religion is in The Muppet Christmas Carol, which turns thirty years old this December. Last fall, I attended a panel to mark this occasion at D23 — the official Disney fan convention — in Anaheim, California. In a packed hall, I watched drag performer, author, and reality-TV-star Nina West (Andrew Levitt, also born in 1978), clad in a stunning Kermit-green dress, sing with several Muppets. Fake snow and greenery decorated the stage.

During the panel that followed, composer Paul Williams (who also worked on music for The Muppet Movie) told us, “I had a spiritual awakening” after giving up drinking — a change that happened just before he wrote for The Muppet Christmas Carol. After telling the story of his sobriety, Williams brought us into his creative process. “I get up in the morning and I say, ‘lead me where you need me.’ And I say, ‘surprise me God,’ because there’s something about surrendering to just the process of living life, and trying to do the right thing, and being of love and service, that just takes all the work out of it,” he explained.

This idea of surrender is a key feature of many religious traditions — particularly Christianity, which is foundational for twelve-step programs. In a Christian context, surrender means giving oneself over to a higher power, to — as Carrie Underwood puts it — let “Jesus take the wheel.” There is surrender, too, in the Muppets — a willingness to abandon the pretense of being “normal,” and instead to give oneself over to irreverence and community, however dysfunctional things might be backstage at The Muppet Show.

For Williams, Scrooge’s story of redemption resonated with his own. “It’s about a man who is addicted to finance… and suddenly has a spiritual awakening,” he continued. “He finds that he is part of the family of man, and he has awakened to a thankful heart. A perfect match of something to write about that I felt I had been gifted with myself.”

The idea that redemption is always available— that hope comes in the morning — is key to the immense popularity of A Christmas Carol. Dickens might have been British, but A Christmas Carol’s message of salvation is also baked into the DNA of U.S. Protestantisms—and into narratives of what America itself means. In The Muppet Christmas Carol, when Scrooge (Michael Caine) faces his own grave, he pleads with the Spirit of Christmas Future: “These events can be changed! A life can be made right!” These are folks who love a comeback story, whether it’s a redeemed politician or a former gang member turned evangelist. There are few more American moves than this promise: Americans long for what might be, for the change on every horizon.

The Muppets are felt-wrapped containers of unfettered possibility. At the close of The Muppet Movie, in a reprise of “The Rainbow Connection,” Kermit turns to the camera — breaking the fourth wall — and sings, “Life’s like a movie, write your own ending, keep believing, keep pretending.” It is a modern affirmation of faith in the regenerative power of creativity — and our control of our own destiny.

(Kermit. Image source: Mike Lawrie/Getty Images)

But this is not just a story of American individualism. Kermit sings on a soundstage where he is surrounded by dozens of other Muppets, in every shape and size. Even more than they are dreamers, the Muppets are a family. They are an emblem for all those who have had to forge their own chosen families — a hallmark of Generation X, which was perhaps the first cohort to celebrate “Friendsgiving,” and also of many LGBTQIA+ people (there are many excellent queer takes on the Muppets). Kermit’s dream lives because he shares it with other people. Catharsis only comes once you have a community.

***

The Muppet Christmas Carol is now a classic, but its spiritual wellspring is different from that of the Henson-era Muppets.

The Muppets’ roots owe much to the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. This was a time of religious experimentation, as Baby Boomers came of age amidst popular interest in Asian religions; as the Jesus movement spread among “hippie Christians” on the West Coast; and as feminism, Civil Rights, and environmentalism all influenced theologies and rituals. Experimentation was a hallmark of American religions in this era. (In The Muppet Movie, there is a running gag where every time any character says they are “lost,” another replies: “Have you tried Hare Krishna?”)

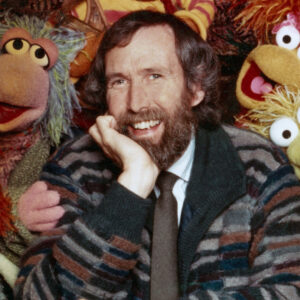

Jim Henson was influenced by that counterculture. Raised in a Christian Scientist family, he eventually left that tradition (Christian Science is one of many late-nineteenth century Christian revivals that could also be called countercultural). As an adult, he was influenced by the beatniks of the 1950s and the peace movements of the sixties and seventies. Many of Jim Henson’s quotes evoke the interconnectedness of all living things. “I believe in taking a positive attitude toward the world,” he said. “I try to tune myself into whatever it is that I’m supposed to be, and I try to think of myself as a part of all of us — all mankind and all life.”

(Jim Henson. Image source: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Attunement, a web of life, unity — this was the romantic hope left over from the 1960s that lingered during my late Cold War childhood (and also inspired Fraggle Rock). This language was passed down to liberal late Gen Xers and millennials through our parents’ nostalgia for the idealism of their youth. We imbibed it through popular culture. And in late capitalism, we are what we consume. To binge The Muppet Show or Fraggle Rock is to binge an entire ethos.

After Henson’s death, he was memorialized as a peaceful harbinger of hope. “I think what Jim really wanted to do was sing songs, and tell stories, teach children, promote peace, celebrate man, praise God, and be silly,” said Muppet writer Jerry Juhl at Henson’s memorial service. “That’s how I’ll remember Jim Henson — as a man who was balanced effortlessly and elegantly between the sacred and the silly.”

Silliness is sacred. Many anthropologists of religion have argued that “play,” or “ludic ritual,” is central to how religious behaviors work. It might seem counterintuitive, but wackiness and holiness often go together: just think of the revelry of St. Patrick’s Day, or the role reversals and crazy costumes on the Jewish holiday of Purim. Literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin made a similar argument about the “carnivalesque.” When things are topsy turvy — when our usual rules are suspended — we can stretch the boundaries of our identities or reverse our social roles. Peasants become queens; pigs become movie stars. It is on the strength of the absurd that we delve into hope and new ways of becoming.

This Hensonian “sacred play” is what made the Muppets so life changing for my generation. “I don’t think we love the Muppets simply because they came from our childhood,” writes Elizabeth Hyde Stevens. “We love the Muppets because they gave us a worldview — a profoundly idealistic, yet profoundly realistic worldview — that many of us carry into our adulthoods.”

***

Why do the Muppets work so well in an adaptation of A Christmas Carol? Victorian literature scholar Joshua Taft writes that Dickens’ A Christmas Carol combines “humanistic Christianity” with “a variety of secular enchantment.” Enchantment — or re-enchantment — is a crucial part of the Muppets’ appeal.

Philosopher Jane Bennett writes that enchantment entails “a surprising encounter, a meeting with something that you did not expect or are not fully prepared to engage.” No one expects to see a frog playing the banjo, or Gonzo cast as Charles Dickens. This interrupts us, introduces “the unheimlich (uncanny),” gives us “a shot in the arm.”

The Muppets re-conjure the world. As puppets, uncanniness is already in their DNA. They are hybrid beings, animated by humans, seemingly independent within the frame of the television screen, but somehow just as believable when we can see the puppeteers beneath them.

Bennett notes the connection between “enchant” and the French word for singing: chanter. “To ‘en-chant’: to surround with song or incantation; hence to cast a spell with sounds, to make fall under the sway of a magical refrain, to carry away on a sonorous stream,” she writes. Fittingly, we find the deepest moments of Muppet enchantment in music.

At the D23 panel, Paul Williams discussed Gonzo’s “soulfulness,” which came out deeply in The Muppet Christmas Carol. But that sense of melancholy wonder was already a part of the character back in the 1970s. As Williams put it, “One of the most amazing experiences of my life was to hear Gonzo sing, ‘This looks familiar…’”

That’s the first line of “I’m Going to Go Back There Someday,” a ballad the blue and purple misfit sings in The Muppet Movie. As the Muppets sit around a campfire, Gonzo marvels at the stars. “I wish I had those balloons again,” he says, remembering a brief sojourn in the clouds. With Rowlf the dog playing a mournful harmonica, the song begins.

In the second verse, Gonzo sings, “Is that a song there, and do I belong there? I’ve never been there, but I know the way. I’m going to go back there someday.” It is a deeply mystical tune, rife with paradoxes. It is also a grounded song. It revels in our vulnerable intersubjectivity with other living beings. “There’s not a word yet for old friends who’ve just met. Part heaven, part space, or have I found my place?” We might long for the sky, but it is the bonds forged below, around the campfire, that matter most.

(Image: Gonzo singing in The Muppet Movie)

Like Henson poised between “the sacred and the silly,” Gonzo is positioned on this same sublime hinge. As Gideon Haberkorn writes in Kermit Culture, “The Great Gonzo provides a situation for negotiating, questioning, and reinterpreting normality as such. His essence is the defiance of norms and boundaries, fervent commitment, and a strong belief in himself.”

Gonzo is the most “soulful” Muppet because he relishes in sacred play. We might dream of being carried away by a giant bouquet of balloons. Gonzo lives this dream.

***

For most of my life, Henson’s untimely demise was the celebrity death that haunted me the most. I’m not sure why. It might have been my age when it happened, on the cusp of being a teenager. The timing of Henson’s death also coincided with a rapid upswing in activism and awareness around the AIDS epidemic (another formative Gen X moment). On the personal front, my paternal grandparents died in the early 1990s. A dear friend lost her sister around the same time.

I had led a relatively sheltered childhood up to that point. In a way, Henson’s loss was the opening salvo in a deluge of deaths.

But perhaps the Muppets had already attuned me to death long ago. Recall Miss Piggy’s mishap with Tony Randall on the Muppet Show? When I first saw her changed to stone, I was certain he had killed her. Or something worse: provoked a kind of living death. She was an immobile statue, but occasionally her voice would shriek out, furious with her situation. It was the very worst kind of uncanny valley — a comingling of absence and presence, on the border between life and death.

Miss Piggy is turned to stone because she stumbles into Randall’s dressing room while he is messing around with a book of spells. He says an incantation out loud before checking to see what it does and — presto, chango! — every molecule of Miss Piggy is transformed. While we might long for enchantment, for Kermit singing about “magic in the air,” there is a danger in re-conjuring the world, too. For it is a fragile one.

The Muppet Christmas Carol acknowledges this fact of the worlds’ fragility and is both a delight and an elegy because of it. After all, Dickens’ original has always hinged on mortality. Scrooge is aghast when he sees the future in which Tiny Tim has died. In the film, he says, “Oh spirit. Must there be a Christmas that brings this awful scene? How can we endure it?” But there is another, more stoic possible take. In character as Bob Cratchit, Kermit tells his wife and children: “Life is made up of meetings and partings and that is the way of it.”

I think of what it must have meant for Jerry Juhl to write that line — which is not in the original —into the script, so soon after Henson’s death, and to give it to the Muppet who was the alter ego of his dear friend.

From “old friends who’ve just met” to “life is made up of meetings and partings.” Is this enchantment? It certainly stops us in our tracks. Lately, I find myself missing Jim Henson more than I ever have before. Henson’s manager and friend, Bernie Brillstein, eulogized him thusly: “In a business where the one who shouts the loudest usually gets the most attention, Jim Henson rarely spoke above a whisper.”

I long for a voice of quiet compassion here in the cruel chaos of a world where the loudest voices are so often vitriolic. Henson’s speaking voice was quiet. Yet the whole world heard him.

Some of us still do. Just ask the hundreds of fans crying buckets as we watched the Muppets in Anaheim last fall.

Jodi Eicher-Levine is the Berman Professor of Jewish Civilization and a professor of religion studies at Lehigh University. She is the author, most recently, of Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis: How Jews Craft Resilience and Create Community, and is writing a book about religion and Disney.