Mucho Mucho Amor, Mucho Mucho Religion

A review of Netflix's documentary about Walter Mercado, an eccentric Puerto Rican celebrity astrologer

If I had been able to read the stars last January, I would have planned a different 2020. Heck, if I could read them now, I would tell you what I’ll be doing next month. Instead, like everyone else, I’ve spent this year stuck in a perpetual present, a sort of pandemic purgatory or (for the lucky) bourgeois bardo that seems to consist mostly of a couch and a Netflix subscription. Low culture, high culture—who cares, so long as it gets you through quarantine.

If I had been able to read the stars last January, I would have planned a different 2020. Heck, if I could read them now, I would tell you what I’ll be doing next month. Instead, like everyone else, I’ve spent this year stuck in a perpetual present, a sort of pandemic purgatory or (for the lucky) bourgeois bardo that seems to consist mostly of a couch and a Netflix subscription. Low culture, high culture—who cares, so long as it gets you through quarantine.

With “comfort culture” extra à la mode in 2020, Much Mucho Amor (dir. Cristina Costantini and Kareem Tabsch) could not have come at a better time. The comforts served up by this feature-length documentary film about astrologer Walter Mercado are manifold: gushing grannies, lavish costumes, and solid-if-sentimental life advice, never mind ambition, betrayal, a witch, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and a Conchita-Wurst drag queen in a rockabilly dress with the Virgin of Guadalupe on the chest. Netflix has a knack for compulsive comforts.

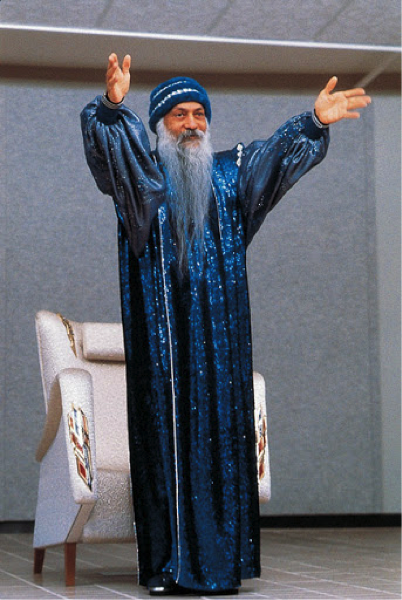

Much Mucho Amor joins a crop of pop-docs (2018’s Wild, Wild Country, 2020’s Tiger King) that repackage a sexually dubious eccentric as soothingly predictable home entertainment. This is an aesthetic achievement of sorts: we thrill to the danger of an Osho or a Joe Exotic, even while sinking into the couch, somehow reassured by his presence. Walter Mercado is an oddity of a different sort. Although he did, as it happens, know Osho (a.k.a. Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh, the Indian “sex guru” whose Oregon commune was investigated by the FBI) he couldn’t be less threatening. Well before Netflix got ahold of him, he’d spent decades spinning his eccentricity into a comforting TV persona—making him the ideal patron saint for our annus horribilis.

And I do mean “saint.” Mercado, who died in 2019, was a religious figure, as comes through clearly in Mucho Mucho Amor. It’s not just that he “almost became like a religion” (as one acquaintance observes) or that “people started wanting to touch him as though he was holier than the Pope” (as another says). That much would be true of any celebrity. It’s that he talked about his astrology in explicitly religious terms. “Why do you mix so many religions?” asks one talk show host in an archival clip, listing off Santeria, Christianity, and “primitive religions” as among those absorbed by his astrology. “Nobody has a monopoly on God,” Mercado replies. He practices an “interfaith religion” that (in this interview at least) seems to consist mostly of the golden rule and the power of positive thinking. This might be New Age pabulum, but it is pure Mercado, parcel of his pleasing persona and key to his comforts. Who wouldn’t want to watch Walter intone his way through the Zodiac, waiting for him to forecast your future and infuse it with his reassuring authority.

And I do mean “saint.” Mercado, who died in 2019, was a religious figure, as comes through clearly in Mucho Mucho Amor. It’s not just that he “almost became like a religion” (as one acquaintance observes) or that “people started wanting to touch him as though he was holier than the Pope” (as another says). That much would be true of any celebrity. It’s that he talked about his astrology in explicitly religious terms. “Why do you mix so many religions?” asks one talk show host in an archival clip, listing off Santeria, Christianity, and “primitive religions” as among those absorbed by his astrology. “Nobody has a monopoly on God,” Mercado replies. He practices an “interfaith religion” that (in this interview at least) seems to consist mostly of the golden rule and the power of positive thinking. This might be New Age pabulum, but it is pure Mercado, parcel of his pleasing persona and key to his comforts. Who wouldn’t want to watch Walter intone his way through the Zodiac, waiting for him to forecast your future and infuse it with his reassuring authority.

Born and raised in rural Puerto Rico, Mercado was always different, a sensitive boy. After he brought a dead bird back to life through prayer, he became known as “Walter of the Miracles.” “This boy has grace of God to heal people,” remarked a neighbor. This otherworldly touch stayed with Walter through a youthful career in stage and film, ultimately landing him the role of a lifetime.

Mercado rose to fame in the 1970s and 80s. He started by giving short astrology reports on the local news—a sort of psychic meteorologist. Soon he had his own show, “Walter, the Stars, and You.” Then that show exploded. He was on Spanish-language TVs throughout the Americas. He developed a following in Brazil and Italy. By the early 1990s, he was becoming a crossover celebrity in the Anglo-U.S., where he was one of the founders of the Psychic Friends Network 1-900 number. Sally Jesse Rafael interviewed him (his perm could eat hers). Howard Stern pronounced him “bigger than Jesus.” He met Glenn Close. And Bill Clinton. He was, in other words, one of the brightest stars in the sky.

Then there was a fall (I’ll avoid spoilers), followed by a redemption. Now Mercado is a millennial darling, the face that launched a thousand memes of the “You know your mom is getting older when she gets a Walter Mercado haircut” variety. You can get Walter Mercado t-shirts and votive candles, and even order a Mercado-themed cocktail with a Tarot card attached.

I regret to say that I had not encountered Mercado prior to Mucho Mucho Amor. In this, I’m probably on par for my demographic: queer white Anglos just a hair older than the meme-hungry millennials. I am thus grateful to this documentary for all kinds of reasons, not least the pleasure of watching it dance with Mercado around the question of his sexuality. Throughout his career, Mercado went out of his way to avoid being labeled as gay. By prancing nimbly around that label—sort of out, sort of not— he somehow managed to become a beloved figure within what the documentary describes as a homophobic Latinx culture. (Without denying the cultural specificity of Puerto Rican homophobia, it bears noting that Anglo-U.S. homophobia was just as capable of constructing a both-out-and-in middlebrow celebrity: cue Liberace’s piano). “Growing up as a gay boy and watching Walter Mercado gave me hope,” explains LGBTQ activist Karlo Karlo. The documentary shares in this gratitude; it is a love letter to Walter, a confession of mucho mucho amor.

I regret to say that I had not encountered Mercado prior to Mucho Mucho Amor. In this, I’m probably on par for my demographic: queer white Anglos just a hair older than the meme-hungry millennials. I am thus grateful to this documentary for all kinds of reasons, not least the pleasure of watching it dance with Mercado around the question of his sexuality. Throughout his career, Mercado went out of his way to avoid being labeled as gay. By prancing nimbly around that label—sort of out, sort of not— he somehow managed to become a beloved figure within what the documentary describes as a homophobic Latinx culture. (Without denying the cultural specificity of Puerto Rican homophobia, it bears noting that Anglo-U.S. homophobia was just as capable of constructing a both-out-and-in middlebrow celebrity: cue Liberace’s piano). “Growing up as a gay boy and watching Walter Mercado gave me hope,” explains LGBTQ activist Karlo Karlo. The documentary shares in this gratitude; it is a love letter to Walter, a confession of mucho mucho amor.

Sexual ambiguity of this sort can feel like a relic of a lost era. To describe Mercado as “gender non-conforming,” as a Miami museum does, is correct of course, as far as it goes. But it’s also to translate his late-20th century sexuality into the terms of the 21st. The same goes for “asexual,” a label placed on him at one point in the film. Our documentarians, Costantini and Tabsch, clearly want to respect Mercado’s right to set the terms of his own sexual identity. And yet their camera can’t resist the voyeuristic impulse to peer around his house, hunting for sexual clues—playing a visual game in which Mercado is a lively, if silent, participant. Clues abound: a Gay Planet DVD, a framed portrait of Oscar Wilde wittily flanking Walter’s own.

No voyeuristic revelation can begin to compete, however, with the audacious weirdness of what Mercado was already doing on TV. At one point, a talk show host asks him if he is a heterosexual. He replies (perhaps winkingly?) that sex for him is “sacred” and “spiritual.” “I have sex with life, I have sex with everything, with clothes, with beauty . . . I’m married to my public, to my people.” Did Mercado die a virgin? Who cares. The “sex” he’s having on screen is way more interesting.

It is impossible to approach this on-screen presence without coming up against the capes. They are central to Mercado’s charms. It would be worth inventing a time machine just to be able to witness in person the gleefully faux-serious catwalk of professional models who flitted across the galleries of the History-Miami Museum at the gala opening of its Mercado retrospective. “Things Just Got Weird,” wrote one attendee on Instagram. Yes, please.

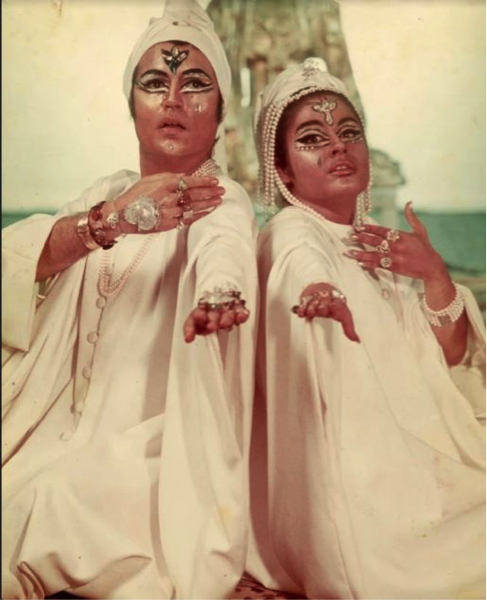

The capes were also central to Mercado’s religious aura. A Miami Herald article that flashes onscreen in the documentary describes Mercado as “swami-like.” True enough. He apparently first sported a cape in the late 1960s, while playing “a Hindu prince” in a low-budget film. He kept up the look when he got his first gig as an astrologer in 1969.

The capes were also central to Mercado’s religious aura. A Miami Herald article that flashes onscreen in the documentary describes Mercado as “swami-like.” True enough. He apparently first sported a cape in the late 1960s, while playing “a Hindu prince” in a low-budget film. He kept up the look when he got his first gig as an astrologer in 1969.

Mercado (left) playing a Hindu prince

Later in life, in the midst of a legal battle over the commercial rights to his brand, Mercado officially changed his name to Shanti Ananda. He got the new moniker from none other than Osho—i.e., Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh, back in his Poona period. Mercado’s wry take on Osho (and on the inimitable, if terrifying, Ma Anand Sheela) did not make the final cut of this documentary. But we do catch a glimpse of an Osho VHS tape in Walter’s living room. More to the point, at least a few of Mercado’s sparkly robes look like they could have been lifted from Osho’s closet.

Osho (a.k.a. Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh) sporting a cape

Clothing matters, the scholars tell us. It has certainly been central to how Hinduism entered global-popular culture, from Swami Vivekananda to Pierre Bernard (“the Omnipotent Oom”) and onto the red-clad Rajneeshis. Mercado, one could say, draws out the implicit camp of these earlier sartorial experiments.

And that’s not the half of it. Here’s Walter in his living room, a faded star ready for his last big interview:

On Walter’s right sit Ganesh and Hanuman; on his left, a jade Buddha and a Tibetan-style bronze of what may be Avalokiteshvara.[1] Behind him are paintings of a resplendent Virgin Mary and a trembling St. Sebastian (that perennial gay icon). Mercado’s sober and restrained taste is evident throughout, whether in the marble-inlay side tables (probably Indian imports) or the jauntily placed crown.

On Walter’s right sit Ganesh and Hanuman; on his left, a jade Buddha and a Tibetan-style bronze of what may be Avalokiteshvara.[1] Behind him are paintings of a resplendent Virgin Mary and a trembling St. Sebastian (that perennial gay icon). Mercado’s sober and restrained taste is evident throughout, whether in the marble-inlay side tables (probably Indian imports) or the jauntily placed crown.

We already know about “guru English.” Here, we have a guru Spanish—or, better yet, a guru Spanglish, shaped profoundly by the cultural-linguistic politics of the Americas, even as it poaches on the postcolonial South Asian English of Osho and others. Mercado’s meteoric rise to fame rode the galactic currents of several empires, most notably that of the U.S., both in its first major phase of overseas expansion (claiming key island territories, like Puerto Rico, away from the Spanish Empire in 1898) and its second—when, after 1947, with the old European empires crumbling, it pivoted to a new model of empire that was primarily non-territorial and predicated on the global power of financial and media institutions (as well as the CIA). This imperially inflected late-modern mediascape structured much of Mercado’s career. He clearly wanted the prestige (and the money) that the status of an American “crossover” star could confer.

This documentary takes these accreted histories and bends them in the direction of Netflix—which is to say, in the general direction of San Jose, CA. The global media behemoth now produces content across a range of languages, including German (Dark), Brazilian Portuguese (3%), and Hindi (Sacred Games). That all three of these shows have either English or numeric titles indicates the extent to which English continues to assert its hegemonic status as “world language” with the backing of California capital. Spanish’s relationship to Silicon Valley English is both part of this general story and also more intimately particular—part of a local history of territorial annexation and settler colonialism. Mucho Mucho feels equally at home in both languages, with interviewees (including Mercado) opting for English regularly throughout. The film thus feels directed simultaneously at two audiences: Latinx viewers who already know and love Mercado, and Anglo viewers poised to fall for him for the first time.

The aesthetes will have gripes, of course. Like everything on Netflix, Mucho Mucho Amor is too long. It exists to eat time, and even at 96 minutes feels padded. Its Tarot-card themed chapter headings can be rather on-the-nose (e.g. “The Hermit”). Its narrative arc can get murky, especially in the second half, and its narrative beats can feel stale. The film opens by declaring a search for a reclusive kitsch celebrity (an arguable echo of the controversial 2017 podcast “Missing Richard Simmons”) before shifting to the familiar rise-and-fall rhythms of VH1’s “Behind the Music” and countless Hollywood biopics. (Like Bohemian Rhapsody’s Freddie Mercury, Mercado is brought down by a handsome-but-nefarious business manager). This version of that tale ends with redemptive angels, the most gloriously seraphic of which is Lin-Manuel Miranda, the superstar Hamilton creator. Miranda’s slightly maudlin gloss on Walter’s wonderful weirdness indicates a larger difficulty. Thanks to Mercado, he gushes, “we have greater acceptance for people around us.” Fair enough. But the kindergarten-comfort of this multiculturalist maxim arguably flattens the specificity that made Mercado a compelling figure in the first place.

Gripes aside, I think anyone interested in modern religion should see this film. I, at least, want Walter to be my spirit guide to the wide, weird world of late-modern religion. Astrology has made a major comeback in recent years among millennials keen for portents of an uncertain future. Now more than ever, we should be reading the history of religion via astrological enthusiasts from Nostradamus to Nancy Reagan. Nor is that all. So many questions echo over this film: What is the relationship between kitsch and camp? How do new media reshape old messages? Will the pandemic accelerate the collapse of everything into the digital?

In forecasting that future, dear reader, I commend you to Walter Mercado. May his stars shine a path through the darkness of our plague year.

J. Barton Scott is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto and the author of Spiritual Despots: Modern Hinduism and the Genealogies of Self-Rule (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

***

[1] The author thanks Dr. Sarah Richardson for help with an iconographic emergency; any errors in identification should be blamed on Mercado’s mood lighting.