Mothers in Zion

The longstanding pressures Mormon women face to be mothers

(Mother Pioneer statue in Salt Lake City, Utah. Source: mormonwomenstand.com)

On March 17, 1842, a group of women met in a small room in the Red Brick Store in Nauvoo, Illinois. Joseph Smith, the man who had unearthed golden plates and spoken with God a few years earlier, was also in attendance, along with two male elders from the church. Smith implored the women to be constantly “searching after objects of charity” and “to assist [the elders] by strengthening the virtues of the female community.” The women decided to form a Relief Society devoted to these principles and elected Smith’s wife, Emma, as its first president. An elder stepped forward, calling her a “mother in Israel” and charged her to “look to the wants of the needy” and to “be a pattern of virtue.”

For years, the Latter-day Saints had hoped to create a sacred city where they could build the Kingdom of God. They called this future holy city “Zion” and themselves Saints. But they were frequently victims of violence, which forced them to flee from their homes in New York to Ohio, Missouri, and finally, Illinois. Emma Smith’s anointing represented the Saints’ hope that they would finally be able to build God’s kingdom. The elders’ promised that she would be exalted and could offer guidance to others. But the Mormon community fractured after Joseph Smith’s death in 1844. Various men tried to claim his prophetic mantle, leading large groups of Saints to Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Utah in search of a new Zion. The largest group of Saints settled in the Salt Lake Valley. These Saints distanced themselves from Emma after she sparred with Brigham Young over his legitimacy as church president.

The language the church leaders used to anoint Emma, however, has continued to influence Mormon debates over the role of women, especially within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. When I first encountered Emma Smith’s story as a graduate student studying American religious history, the image of her assuming the leadership of the Relief Society was powerful. As a “Mother in Israel,” Emma cared for impoverished women, blessed the bodies of pregnant women, and anointed the sick. Even within my own religious upbringing as a white Protestant, I rarely encountered examples of female spirituality that included such a robust vision of how God might use women to heal people. As I read further in Mormon history, however, I discovered that the church’s definition of motherhood was not always empowering. Over time, the term “Mother in Israel” was flattened to refer to the idea of motherhood itself. Latter-day Saints imbued this idea of motherhood with political as well as religious meaning. In the nineteenth century, Latter-day Saints defended their practice of polygamy by referencing their language of motherhood, arguing that the willingness of Latter-day Saint women to bear multiple children demonstrated their virtue. Latter-day Saint leaders also decried birth control, even as some Saints continued to use herbal teas, sponges, and other types of contraception to control their fertility.

The church’s decision to publicly end the practice of polygamy in 1890 allowed Latter-day Saints to move closer to the American mainstream. But that did not end their involvement in debates over sexuality and marriage. In the 1970s, for instance, Latter-day Saint leaders saw feminism as a challenge to male priesthood authority. They also feared that increasing the number of working women would lead some to neglect their role as mothers. As a result, Latter-day Saint (LDS) leaders railed against changing understandings of the family and women’s role in the world. Drawing on theology that Latter-day Saints originally developed in the early twentieth century, these leaders argued that women were already equal to men within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as motherhood was the equivalent of male priesthood. The continued repetition that Latter-day Saint leaders placed on this idea meant that many women felt a compulsion to have children. When Latter-day Saint feminists challenged this idea, they often drew on Mormon history – and Emma Smith as the prophet’s wife – to argue for women’s spiritual and political authority, a battle that continues today.

Defending Polygamy

Despite the declarations of today’s Mormon feminists that their claims to spiritual power are rooted in the experiences of early Latter-day Saint women, Mormon history does not offer a precise model of women’s empowerment or disempowerment. Some women embraced the role that early Mormonism offered them, blessing the bodies of pregnant women and claiming access to divine knowledge by speaking in tongues. Polygamy allowed women like Ellis Shipp to attend medical school without worrying about childcare since their sister wives could attend to their children’s needs in their absence. Others, however, found the church and the practice of polygamy stultifying.

In the nineteenth century, many Americans believed polygamy was as horrible as slavery. The 1856 Republican National Convention referred to polygamy and slavery as “twin relics of barbarism” and argued that they needed to wipe out both practices to ensure American liberty continued. But Latter-day Saints defended polygamy by contrasting the moral corruption of the wider world with their own virtuousness. In 1857, for example, a Latter-day Saint apostle named Heber C. Kimball accused Protestant ministers of being “the biggest whoremasters… on the earth.” He did not limit his critique to religious leaders. Instead, he suggested that “the gentlemen of the Legislature” also engaged in frequent sexual liaisons with women who were not their wives. Most men, he suggested, had “two to three, and perhaps half-a-dozen private women.” He insinuated that these individuals used abortion to allow them to “gratify their lust” without consequence.

Kimball contrasted the behavior of the mainstream Christian world and his American Zion. Unlike the United States as a whole, he reassured his audience that the Saints did not practice contraception or abortion. In the nineteenth century, Americans frequently used douching, herbal teas, and condoms to prevent pregnancy. When these methods failed, they could turn to various mechanical or pharmaceutical methods for ending a pregnancy. Kimball admitted that his wife had learned to control her own reproductive capacities as a young woman. Her family and friends encouraged her “to send for a doctor and get rid of the child.” The apostle described the ubiquity of abortion in the early nineteenth century by saying it was “just as common as it [was] for wheat to grow.” By 1857, however, Kimball no longer believed that abortion was an acceptable way to control reproduction. Like many Americans, he saw it as sinful and used its practice to discredit other religious communities.

Other Latter-day Saints used similar language to challenge Protestant morality. In 1885, for example, H.W. Naisbitt asked people to judge the Christian world “by its fruits.” He felt that its embrace of monogamy had resulted in hypocrisy and degradation. “What of the whoredoms, the adultery, the fornication, the prostitution of women in monogamic nations?” he asked. “What of sexual diseases, of blighted lives, of martyred women, of little graves dotting every hillside and the resting places of the dead? What of feticide, infanticide, and abortion?”

Latter-day Saints placed the image of the Mormon mother against these images of female destruction. Brigham Young suggested that it was impossible for Mormon women to be “seduced” into having extramarital sex. Another Mormon leader connected polygamy to the exaltation of women in the Bible. He pointed out that “Rachel, Ruth, Hannah, and others, who [had] honored God’s law” had “[become] the mothers of Prophets, Priests and Kings.” When a Mormon woman died, the church leaders who gave her funeral orations applauded her for the care she had provided her children and lauded her as “a mother of Zion.”

(Source: History.churchofjesuschrist.org)

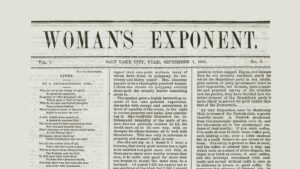

This language did not recognize the pain that polygamy caused many female Saints or the real danger pregnancy posed to women. The Mormon women’s rights advocate Emmeline B. Wells famously defended polygamy in the newspaper editorials she published in the Woman’s Exponent from 1877 to 1914, while privately decrying the loneliness she felt from her husband’s frequent absences. She was not the only wife in a plural marriage whose private experiences became the subject of public debate. English common law made polygamy illegal. In the nineteenth century, the United States federal government used laws against polygamy to place pressure on the LDS church, frequently arresting and imprisoning male leaders. Women were usually exempt from prosecution, but not always. In 1883, Belle Harris was jailed for refusing to answer a Grand Jury’s questions about who had fathered her child. Her refusal to respond appropriately resulted in her imprisonment in the Utah Territorial Penitentiary in Salt Lake City with her infant son. Latter-day Saints women brought her “refreshments” and small gifts. They meant these gifts to be a reminder that her imprisonment was unjust. The penitentiary, on the other hand, refused any suggestion that Harris was different from other female prisoners and temporarily jailed her with a prostitute.

In 1890, the President of the LDS Church suspended the practice of plural marriage. He hoped it would end the federal prosecution of polygamy. The practice’s end was uneven. Some Latter-day Saints quietly refused to abandon polygamy. Plural marriages continued secretly among mainstream Latter-day Saints causing the church to issue a second manifesto in 1904, outlawing the practice. Some women saw the end of polygamy as a loss. The practice allowed them to develop careers outside the home without worrying about childcare. Still, others feared their husbands would abandon them for their sister wives. These women wondered what value the sacrifices they had made for polygamy had now that the practice had ended. Others breathed a sigh of relief. Not all young women had embraced the practice, and many likely hoped to have marriages that more closely mirrored the plots of popular romance novels.

The national debates over polygamy had also placed women’s bodies at the center of disagreements over polygamy. Latter-day Saint leaders had pointed to women’s sexual purity and willingness to have children as evidence of polygamy’s fundamental soundness as a marital system. The end of polygamy meant that Mormon women would no longer be at the center of a debate over managing sexuality. Instead, Latter-day Saints embraced mainstream understandings of how families should be structured. With polygamy no longer possible, Latter-day Saints changed how they defined marriage. In the 1920s and 30s, they accepted monogamy.

In the mid-twentieth century, however, Latter-day Saints would again see their families as under threat. This time, however, the danger came from widespread social change and challenges to how Americans structured their families. Latter-day Saint leaders encouraged their followers to reject feminist claims to empower women. Instead, they encouraged Mormon women to see themselves primarily as mothers. Some Mormon women, however, embraced feminism. For them, Mormon history would provide alternative models of what it meant to be a godly woman or, to use the words that had anointed Emma Smith in the 1840s, a “mother in Israel.”

Defending against Feminism

In the 1970s, a group of Latter-day Saint women living in Boston met to discuss the burgeoning women’s movement and what it might mean for their own lives. They considered the emerging popularity of “Betty Friedan, Kate Millet, [and] Rodney Turner” even as they mused about lessons from their church. The women emphasized that they did not identify as radical feminists. “We spend no time railing at men,” one of the women explained in a manifesto published in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Instead, they fit “the standard model for Mormon womanhood.” They embodied “the supportive wife, the loving mother of many, the excellent cook, the imaginative homemaker and the diligent Church worker.” Although many of the women eventually became more radical, they initially emphasized the balance they had found between expanding women’s power and sustaining male authority.

The women also turned to Mormon history to understand how they might develop a uniquely Mormon understanding of feminism. On the shelves of Harvard’s Widener Library, they found copies of the Woman’s Exponent, a nineteenth-century Mormon women’s newspaper that supported women’s suffrage and polygamy. One woman described the thrill they experienced as they read “bound volumes” of the paper. “I couldn’t stop reading,’ she wrote in an article nearly fifty years later. “The Woman’s Exponent amazed me. These articles were written by articulate, opinionated women about a broad spectrum of women’s issues. These women were feminists!” In response to the excitement of discovering an early Mormon newspaper that supported women’s activism, the Boston women began publishing their own magazine. They called it the Exponent II. The women wrote about various feminist issues, including infertility, working mothers, and their difficulty maintaining an identity apart from motherhood. Reprints of classic articles from the original Exponent ensured that the feminism they developed was thoroughly Mormon.

The church’s leadership found the emergence of Mormon feminism troubling. The social movements of the previous decade challenged the fixity of gender roles. Feminism called for women to shape political and business worlds beyond the home. Latter-day Saint leaders worried that feminism would desex women by masculinizing them and distance them from their god-ordained role. They responded by reasserting the importance of family and calling upon women to reaffirm their position as mothers.

In 1974, an LDS General Authority bemoaned “the confusion” that led women “to go to work.” He advised Latter-day Saints to be wary of the allure of having enough money to buy “luxuries” even if they were “cloaked in the masquerade of necessity.” He felt these things were too often “satanic substitutes for clear thinking.” A decade later, apostle Ezra Taft Benson gave a talk on motherhood. Explicitly invoking the term “Mothers in Zion,” he reminded the Saints that “home and family” were “at the very heart of the gospel.” He urged women to remember that their primary purpose was motherhood. They should not waste their lives on “material possessions, social convenience… [or] professional advantages,” for these things were “nothing compared to a righteous prosperity.” After he finished his speech, the church published it as a pamphlet featuring a mother gazing lovingly at her son on its cover. Benson and other conservative Latter-day Saints believed that men had an equally powerful role in promoting the gospel. In the 1970s, most Latter-day Saints equated priesthood, which the church defines as the “power and authority…to act” in God’s name, with maleness. All white Mormon men had access to the priesthood, which allowed them to receive revelation and even heal the sick. Those abilities formed the source of their authority in the home.

At times, church leadership cautioned women against aiming for too much power. One Latter-day Saint leader warned women against striving for access to the priesthood. “We men,” he wrote, “know the women of God as wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, associates, and friends.” In the following line of his address, he explicitly qualified his statement with the reassurance that “you seem to tame us and to gentle us, and, yes, to teach us and to inspire us.” Later, the Latter-day Saint leader referenced the founding of the Relief Society as evidence that God had provided men and women with different roles. He believed that God had “assigned compassionate service” to women through its founding just as men had been asked to undertake different, “more labored” tasks. Some Latter-day Saint women found his descriptions of motherhood deeply meaningful. They appreciated the importance that he placed on an activity that was often exhausting in its day-to-day details. Some LDS women felt the feminist movement had devalued their role as mothers and that feminists unfairly maligned women who chose to forego a career to care for their children. For these women, the church’s emphasis on motherhood reaffirmed their own reproductive choices.

Other women found inspiration for a different vision of Mormon womanhood rooted in texts from historical archives such as the Church History Library. The women who met in Boston were only one such example. Some Latter-day Saints turned to Emma Smith and the founding of the Relief Society for inspiration. In 1992, the feminist scholar Maxine Hanks argued in Mormon Women and Authority that Emma had “received ‘a portion of the keys of the kingdom’” during the rituals that accompanied her appointment as Relief Society President. She saw this language as invoking the Mormon idea of the restoration, in which God had given Joseph Smith and the men who followed him the “keys” of the priesthood. These keys allowed them to perform important rituals and to receive revelation from God. According to Hanks, early Mormon women also saw themselves as priestesses. “The women’s Relief Society,” she writes, “…was a benevolent society as well as a self-governing ‘kingdom of priests.”

Two decades after the publication of Hanks’s article, a Latter-day Saint feminist drew upon similar language to argue that Joseph Smith had radically reimagined the nature of God to include a female deity. She argued that the “conventional trinity” comprises a “thrice-reiterated maleness.” The woman saw Joseph Smith as providing an alternate view in which God was plural and included a physically embodied Heavenly Mother and Heavenly Father. Together, these two beings produced the souls of all humanity. The scholar argues that Joseph organized the priesthood after the heavenly family, creating “Queens” and “Priestesses of the Most High God,” as well as kings and priests.

These feminist writings have offered Mormon women a way to reimagine their relationship to motherhood. They present a vision of God in which female and male attributes are celebrated. However, a year after Hanks published Women and Authority in 1992, the church excommunicated several scholars in a wave of excommunications that became known as the September Six. The other feminist was not formally expelled from the church, but some Latter-day Saint scholars suggested that the church punished her by sidelining her within the Maxwell Institute, a church-run research center. LDS women who watched the punishment of feminist theologians became less willing to offer their own interpretations of Mormon scriptures.

As part of its thirtieth-anniversary commemorations of the September Six, the editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought asked me to contribute a piece reflecting on how the event changed Mormon history and society. What quickly became apparent was how much Mormon feminists still felt obligated to honor motherhood and male authority.

In the memoirs of Mormon women published since the September Six, women describe how they must fulfill the expectation to marry and have children. The possibility that they would attend graduate school or spend significant time traveling abroad collides with the probability that they will marry young and become mothers.

Even those women who rejected the advice that they prioritize motherhood could not fully escape cultural expectations. One Mormon woman, Julie Hanks, was in high school when she heard apostle Benson admonish women to give up “social convenience” to raise large families. She felt called to be a musician and knew that following her desires would mean turning away from the prophet’s call to motherhood to prioritize her musical career. She felt “shame” and anxiety that her decision would harm her children and marriage. In another instance, an unmarried Latter-day Saint woman felt compelled to control her own burgeoning sexuality. She struggled “to keep from moving [her] hand toward [her] own body—committing the sin of masturbation.” She also knew, however, that none of the people who advised her to maintain her virginity until marriage had been celibate as adults. She longed to tell her mother that “no prophet or apostle [had] lived a celibate life.” Another woman wrote simply, “Pregnancy is not my birthright.” Although she decided to have a child, she could not accept that her status as a mother was her “essence.”

When Mormon elders pronounced Emma Smith a “Mother in Israel,” they did not see the term as limited to childrearing. The same title was given to Eliza R. Snow, an early Mormon poet who remained childless despite being married to Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. In the nineteenth century, the term “Mother in Zion” cast women as godly role models to whom others could look for advice and comfort. But in the twentieth century, Mormon women found little support within their communities for alternative visions of womanhood. Mormon feminists, however, have continued to find inspiration in their faith’s history and theology.

In 2004, Lisa Butterworth founded a blog named Feminist Mormon Housewives. Now defunct, it explored the intersections of Mormon culture and feminism. Like the women who discovered Mormon feminism on the shelves of Harvard’s Widener Library, they often connected their experiences to those of Mormon women in the past, publishing essays on Joseph Smith’s “forgotten wives” and the blessings that LDS women performed during childbirth during the nineteenth century. The community the women created opened new possibilities. The blog called for a reconsideration of the value of motherhood and women’s roles within the church. It also became a space for women to talk about their difficulties during childbirth and pregnancy. The feminist blogger Lindsay Hansen Park began an essay on her ectopic pregnancy with the words, “I had an abortion.” Another woman wrote about having her cervix dilated after a miscarriage to remove any remnants of the pregnancy to prevent the development of a life-threatening infection.

Although Feminist Mormon Housewives published essays on reproductive rights and abortion, it was never as full-throated in its defense of women’s bodily autonomy as other feminist blogs. Like many Mormon feminists, its bloggers often described their feminism as a journey from accepting the importance of traditional family values to realizing that other models of womanhood existed. Many of the bloggers had haltingly moved toward feminism, and their essays reflected their struggle to reconcile their faith with an emerging recognition that the church promoted male over female power.

Over time, many of these essays focused on women’s demands that the church recognize them as priestesses. In Feminist Mormon Housewives, priesthood came to mean more than the ability to perform certain religious rituals. It represented the authority to speak about their experiences and author their own lives. Like earlier Mormon feminists, they used Emma Smith’s calling as President of the Relief Society and the blessings that women gave to each other to frame their own arguments for increased female authority within the LDS Church. They also asked the women who participated in earlier feminist movements to participate in the blog. The Mormon historian Claudia Bushman, who had been involved with the initial movement in Boston, wrote a blog post in 2007. It focused on how history could inform feminism. She recounted the beginnings of the Relief Society in 1842. She did not, however, focus on Emma Smith’s election as President. Instead, she called her readers’ attention to a revelation that Emma received through her husband. According to Bushman, the revelation asked Emma to “expound scriptures and to exhort the church.” Bushman tasks readers to imagine “what the church would look like if Emma had exercised this opportunity.” She argues that this passage suggests that God saw Emma “as a church worker, a leader, an adult and as a wife, not a housekeeper or even a homemaker.” The Emma that Bushman constructs is not inerrant. She sees women’s subordinate status as partially the result of Emma’s inaction. Bushman insists, however, that God saw Emma as more than a mother, and that Mormon women today can aspire beyond the limits of motherhood as well.

Amanda Hendrix-Komoto is an Associate Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy at Montana State University.