Measuring Salvation in Chains and Corpses

An excerpt from “White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization”

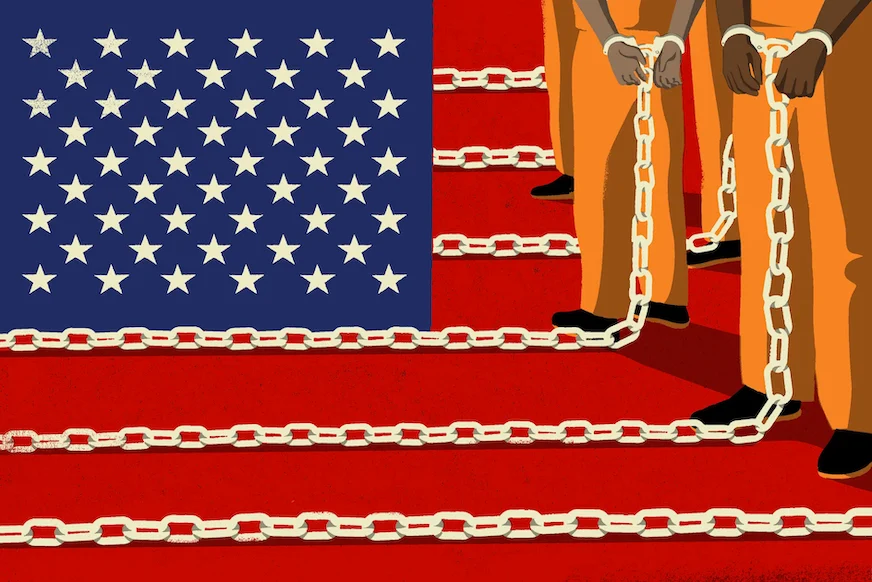

(Image source: Golden Cosmos/The New Yorker)

The following excerpt comes from Andrew Krink’s book White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization (NYU Press, 2024). The book explores the religious and racist functions of America’s policing and prisons.

This excerpt comes from the book’s fifth chapter.

***

In James Baldwin’s November 1970 letter to Angela Davis, he reflected on the meaning of the ongoing reality of “chains on black flesh.” “Dear Sister,” he writes, “One might have hoped that, by this hour, the very sight of chains on black flesh, or the very sight of chains, would be so intolerable a sight for the American people . . . that they would themselves spontaneously rise up and strike off the manacles. But no, they appear to glory in their chains; now, more than ever, they appear to measure their safety in chains and corpses.” Aren’t chains a relic of history? Why do they persist? Three hundred years before Baldwin ever put pen to paper, the European aspiration to a transcendence obtained through chains on Black flesh helped give birth to the whiteness by which some come into what Du Bois called “ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” at the expense of others. For the inherently oppositional force of whiteness to be something like divine—socially and politically omnipotent, infinite, transcendent, invulnerable—Blackness must be damned to chains, rendered powerless, captive, exploitable. This means that the modern history of chains and corpses—from chattel enslavement to carceral confinement and beyond—is not arbitrary, without reason, but purposed, a manifestation of a world-possessing desire at the heart of the eurochristian project. Chains continue to capture Black flesh, Baldwin suggests, because the idolatrous, pseudo-religious aspirations to absolute safety, power, and control inherent to racial capitalism demand it. There can be no safety, no salvation, the mortal gods of eurochristian order tell us, without damnation.

“Safety Instead of Life”

To be human is to be finite, mortal, to live facing the reality of one’s own end—and, increasingly, in our time, the end of the world as we know it. To be alive, in other words, is to be vulnerable. At the most fundamental level, then, the desire for safety is inherent to human existence: the world can be a mortally dangerous place, and we are right to want to survive those dangers, to be safe in the midst of them. And yet, what begins as a natural desire often transforms into an illusory desire for a safety that is absolute, invulnerable, even transcendent—what Baldwin calls “safety instead of life.” The pursuit of absolute safety requires total control of one’s environment, especially of those who are perceived as threats to individual or collective well-being: if I can control the movement and agency of others, the illusion posits, then I can obtain a semblance of control over my own existence, my own destiny. In the end, controlling others necessitates force, coercion, even elimination, which is why, on a mass scale, the pursuit of “safety instead of life” is an inherently “genocidal” pursuit: it requires the destruction of anything that interrupts the mirage of its heavenly destination. Absolute safety requires absolute control, and absolute control requires violence.

The desire to transcend human vulnerability and become like God in relation to the Earth and its peoples is a desire generated by fear of finitude, fear of scarcity, and thus a fear of others. This anxious aspiration to pseudo-divine transcendence and power is the story of patriarchal and possessive whiteness and the mass violence and dispossession it has wrought over the past three to four centuries. For whiteness and property to transcend finite vulnerability—to be like God—others must be posited as inferior to their own sacred power and dehumanized and exploited as such. Indeed, whiteness and property manifest the self-aggrandizing paranoia and fear that are central to the liberal mythology of the origins of the state, a mythology that, in the words of Mark Neocleous, “makes human beings see in others not the realization of their sociality and freedom but rather the barrier to them.” Under such a rationale, “we come to see other members of civil society as a threat or source of harm,” thereby turning “each of us into a source of the other’s insecurity.” Treating the vulnerabilities of finite, creaturely existence as threats to be avoided rather than means of life-giving communion with others or with the divine, the religiosity of patriarchal and possessive whiteness at the heart of US society seeks “refuge” by terminating everything in its way, which eventually includes even itself: “as long as white Americans take refuge in their whiteness—for so long as they are unable to walk out of this most monstrous of traps—they will allow millions to be slaughtered in their name,” Baldwin writes to Angela Davis. “They will perish (as we once put it in our black church) in their sins—that is, in their delusions.” To pursue safety instead of life is to pursue death—death for others and eventually for oneself as well.

The desire to transcend human vulnerability and become like God in relation to the Earth and its peoples is a desire generated by fear of finitude, fear of scarcity, and thus a fear of others. This anxious aspiration to pseudo-divine transcendence and power is the story of patriarchal and possessive whiteness and the mass violence and dispossession it has wrought over the past three to four centuries. For whiteness and property to transcend finite vulnerability—to be like God—others must be posited as inferior to their own sacred power and dehumanized and exploited as such. Indeed, whiteness and property manifest the self-aggrandizing paranoia and fear that are central to the liberal mythology of the origins of the state, a mythology that, in the words of Mark Neocleous, “makes human beings see in others not the realization of their sociality and freedom but rather the barrier to them.” Under such a rationale, “we come to see other members of civil society as a threat or source of harm,” thereby turning “each of us into a source of the other’s insecurity.” Treating the vulnerabilities of finite, creaturely existence as threats to be avoided rather than means of life-giving communion with others or with the divine, the religiosity of patriarchal and possessive whiteness at the heart of US society seeks “refuge” by terminating everything in its way, which eventually includes even itself: “as long as white Americans take refuge in their whiteness—for so long as they are unable to walk out of this most monstrous of traps—they will allow millions to be slaughtered in their name,” Baldwin writes to Angela Davis. “They will perish (as we once put it in our black church) in their sins—that is, in their delusions.” To pursue safety instead of life is to pursue death—death for others and eventually for oneself as well.

What Baldwin calls safety, Neocleous and other scholars of police power call “security,” the illusory aspiration at the heart of racial capitalist order. The mass wealth-generating dispossession on which racial capitalism depends produces populations deprived of the means of subsistence, which in turn threatens the system’s security. Capital, in other words, is inherently insecure and proliferates further insecurity, which in turn gives rise to a politics centered around maintaining the order’s security, no matter the cost. Central to the task of securing order is the power of police. When racial capitalist orders speak of police and prisons as institutions of “public safety” or “security,” then, they are talking primarily about the safety and security of racial capitalist order itself and its managers and beneficiaries, as opposed to all people living under that order. Police power is the power to eliminate threats to sacred social order. And yet, the insecurity that racial capitalist settler colonial order creates through mass dispossession can never be fully eliminated so long as the order keeps on dispossessing and destroying nearly everyone and everything in its path, which it must do in order to survive. At best, the disorderly outcomes of racial capitalist inequality can be managed but never eliminated. Thus, the pursuit of absolute safety and security is ultimately futile, unattainable, an illusion. Nevertheless, the state continues to pursue its own fragile security, at immense human and public financial cost.

In pursuit of its own security, racial capitalist settler colonial order transforms the organic human desire for safety into a weapon with which to force others into either subjection or manufactured consent to its own pseudo-godlike power. At nearly every stage of racial capital- ism and settler colonialism—from the first slave patrols in Barbados to present-day ruling-class rhetoric about the urgent need for more cops and cages to combat “rising crime”—the police and carceral power to control the enemies of God and order have been framed as means of producing a general “safety” for all. The reality is that police and carceral power have, from their beginnings to the present, been concerned above all with pursuing the ultimately unattainable security of hierarchical order and the safety of its white propertied managers and beneficiaries, all at the expense of the many lives cast outside the bounds of racial capitalist belonging.

The Religion of Safety

At the end of the day, the deeply revered idea that cops and cages keep us safe amounts to a kind of religious devotion, what Charles Long calls “orientation in the ultimate sense.” For many people, especially most white people, the idea that cops and cages are natural, that they have always been with us, and that they make us safe is so seemingly self-evident that it rarely warrants any further investigation. Thus, to suggest otherwise registers, for many, as a kind of sacrilege that elicits scorn that is at once religious, racial, and classed in nature. The religiosity of mass consent to state violence is an expression of the structured opposition inherent to phenomena—like whiteness, property, and the racial capitalist state—that need a demonized “criminal” enemy in order to exist at all. To put it another way, the functionally religious quest for transcendent safety is a quest animated by fear—the kind of fear that ultimately devolves into vigilance and then violence against its own shadows that it unwittingly casts on the wall.

In Baldwin’s 1962 essay “Down at the Cross,” he writes of the fear that animated the religiosity he first experienced as a young Black teenager in Harlem. “I became, during my fourteenth year, for the first time in my life, afraid—afraid of the evil within me and afraid of the evil without.” Afraid of himself, the world, others, everything, Baldwin inherited and embraced the idea that “God and safety were synonymous.” Indeed, he writes, “The word ‘safety’ brings us to the real meaning of the word ‘religious’ as we use it.” Demarcating sacred from profane, orderly from disorderly, pure from polluted, religion, broadly construed, provides structures of meaning and orientation that make it possible to live in a world that might otherwise seem chaotic. In many cases, such demarcations draw distinct boundaries between “us” and “them,” which is to say, between the safe and the dangerous. Whatever or whoever disrupts such a deeply revered sense of order destroys the sacred boundary that protects us from danger, thereby jeopardizing not only the sacred but life itself. As such, whatever preserves moral and cosmic order by defending and maintaining the boundaries that protect it fulfills what amounts to an inherently religious function.

In the popular western imaginary, cops and cages not only make us safe but save us. To make safe is to save: the English terms “save” and “salvation” derive from the Latin salvus, meaning “safe,” and the Late Latin salvare, meaning to “make safe, secure.” The original Latin term for “save” later evolved through French and into English to convey acts that “protect,” “redeem,” “rescue,” “preserve,” or “deliver” from danger, death, or eternal damnation. Bearing both general nonreligious and explicitly religious meanings throughout its usage, the multiple dynamics signified by safety and salvation are, both etymologically and conceptually, deeply intertwined, perhaps even inextricable.

Predominant conceptions of sin and salvation in the Christian tradition hold that sin consists in a disorder-generating refusal to be subject to a benevolent and sovereign God, a refusal that establishes a state of condemnation and debt, and that salvation consists in a debt-satisfying sacrifice or punishment that restores cosmic order by restoring humans to proper life-giving subjection to God. From Augustine to Anselm to Calvin and beyond, the sacrifices of debt payment, punishment, and death not only “satisfy” divine justice but save, which is to say, “make safe.” For such theologies, the salvation that sacrificial death generates is the restoration of the necessarily hierarchical divine-human relation, a relation understood to benefit and thus save humanity. Just as the sacrificial punishment and death of the God-Man Jesus restores divine order in the wake of its sinful disruption, so the sacrificial punishment and death of “criminals” restores the sacred social order disrupted by its disorderly desecration, either by restoring dispossessed peoples to their proper subjected place within social hierarchy or by channeling social and racial antagonisms to eliminate “sacrificable” peoples altogether. The eliminatory violence of penal and mortal sacrifice is not merely an act of negation, therefore, but an act of creation and an act of sacralization. The punishment and death of some secures—saves—life for others.

The Violence of Salvation

Police and carceral power, at their root, are manifestations of the godlike, patriarchal power to manage the social household, to keep it in order, by whatever means necessary. From the point of view of the lawmaking managers of order, refusing one’s place in the social household disrespects and damages not only the household but oneself as well. As such, the managers and beneficiaries of order, along with those who consent to their rule, often characterize forced return to subjection as a kind of salvation both for the larger society and for those whom they make subject, in the sense that it habituates disobedient people to the redemptive discipline of obedience in a context of control made necessary by their allegedly corrupted nature. As legal scholar Markus Dubber, writing on the rationale of vagrancy laws, puts it, “Any correction inflicted for such an offense . . . occurs for the benefit of its object as a member of the household, and therefore ultimately for the benefit of both the micro and macro household and its respective heads.” A vagrancy statute passed in Maine in 1821 gave local “Overseers of the Poor” the police power to capture vagrants who failed to productively contribute to the social household and to take them to a workhouse where they would be habituated to their proper place and practices within the social order. An 1834 Maine Supreme Judicial Court decision in the case of a woman taken to a Portland, Maine, workhouse for vagrancy upheld the statute on the basis of the patriarchal idea that subjection under state confinement was a sacred benefit not only to the community, which, through her social elimination, was “preserve[d] . . . from contamination,” but also to the woman herself. As the court wrote, “When enlightened conscience shall do its office, and sober reason has its proper influence, she will regard the imposition as parental; as calculated to save instead of punishing.”

The first European and American prisons were likewise structured around the idea that violent subjection was salvific in that it restored sacred social order by restoring those who disrupt it to life-giving subjection to divine and political authority. In the context of chattel slavery and its police afterlives, the police power to control the movement and activity of enslaved and formerly enslaved Africans was said to be necessary both for African peoples, who, according to white people, were made for subjection, and for the white social order that sought to contain the dangerous threat of disobedience that African peoples posed if left unrestrained. Similarly, in the context of early European-American settler colonialism that claimed the divinely ordained and godlike right to “ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” the violence of police power that made it possible was said to be a means of saving not only a settler society regularly cast as a kind of heaven on Earth but also, perversely, the Native peoples victimized by that violence. As the authors of Red Nation Rising, quoting Sherene Razack, write, “The violence of the settler colonial state against the Native is depicted as a purifying violence, a violence that releases the Native from her subjugation, in which ‘killing becomes saving, and murder brings redemption.’” Present-day police similarly often characterize broken windows policing as a benefit to those whom it targets, including unhoused people who obtain temporary “shelter” and “services” through confinement in jail.

Another example of the racial capitalist patriarchal police logic that holds that criminalization and salvation can take place at the same time is the case of the Hamilton County, Tennessee, sheriff deputy Daniel Wilkey, who, around 10:00 p.m. on February 6, 2019, followed Shandele Marie Riley as she left in her car from a gas station before eventually initiating a traffic stop. During the encounter, Wilkey assaulted Riley by groping her during a body search and ordering her to remove and shake out her bra. After searching her car and allegedly finding a single marijuana roach in a box of cigarettes, Wilkey told Riley that she could avoid being arrested by being baptized, receiving only a citation instead. Riley reports that Wilkey both called her a “piece of shit” and asked if she was “saved,” telling her that he felt God’s spirit while he searched her car. After agreeing, under coercion, to being baptized, Wilkey took Riley to a nearby lake, where Wilkey stripped out of his deputy uniform down to just a T-shirt and underwear and waded with Riley, who refused Wilkey’s request to remove her clothes, into the frigid lake waters, where he assaulted and baptized her while another deputy filmed it all with his phone. While Wilkey’s actions may seem exceptional, the reality is that they simply express in unusually explicit form the mythological synthesis of violence and salvation that lies at the heart of police power more broadly. In other words, calling Riley a “piece of shit” and sexually assaulting her and at the same time “saving” her by baptism are, for the police and carceral imaginary, not mutually exclusive. Like the penitentiary, vagrancy laws, slave patrols, and colonial police power deployed against dispossessed peoples from the early modern period to the present, Wilkey’s actions sought to save the social order precisely by “saving” Riley via violence, returning her to proper subjection to the state and to God, in so doing returning both to the state and to God “the subject [they] had lost.”

Or at least that is what police mythology tells us. Despite the perennial ruling-class claim that police and carceral power benefit both those who are targeted by it and the social order that is rid of their presence, the reality is that, for subjugated peoples, forced subjection feels a lot less like salvation and a lot more like damnation to hell on Earth. Thus, in the end, the forced restoration to proper subjection of people marked as criminal constitutes salvation not primarily for those who are held captive but for the managers and beneficiaries of racial capitalist settler colonial order who are able to enjoy their illusory heaven precisely because others are confined to hell. The functionally sacred order that revolves around patriarchal and possessive whiteness measures its safety—its save-ty, its salvation, and ultimately its godlike power—in chains and corpses.

Andrew Krinks is an independent scholar, educator, and movement builder based in Nashville, Tennessee, where he has taught at Vanderbilt University Divinity School, Lipscomb University, and Tennessee State University. His writing on religion and abolition has appeared in multiple journals and edited volumes.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 57 of the Revealer podcast: “Police, Prisons, and the Religion of Mass Criminalization.”