Malcolm X: Why El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Matters

What Malcolm X's teachings during the last months of his life, after he converted to Sunni Islam, can teach us about racial justice today

(Malcolm X in Mecca, 1964)

From April 13th to May 13th this year, able-bodied Muslims around the world will abstain from food, drink, and sex, as well as baser instincts like anger, from sunrise to sunset for Ramadan, an annual religious obligation named for the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar. April 13th also marks fifty-seven years since Malcolm X traveled to Saudi Arabia to take part in the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca and sacred duty Muslims must carry out at least once in a lifetime if they have the means. The concurrence of these events offers an opportunity to re-examine Malcolm X’s words and work, which resonate now more than ever. The last ten months of his life, from April 1964 to February 1965, deserve particular attention. It was during this time that Malcolm X became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

The parallels between 1960s and 2020s America are depressingly inescapable. Communities of color, including Asian, Black, Indigenous, and Latino Americans, continue to be disproportionately targeted by police brutality, health inequities, education disparities, housing discrimination and redlining, environmental injustice, and voter suppression. Moreover, the United States continues to be threatened by white nationalist terrorism, which relies on rhetoric of victimhood and hate to justify violence. No longer in the guise of white hoods and the KKK, this violence is now expressed by a complex constellation of groups and organizations targeting Asian, Pacific Islander, Black, Indigenous, and Latino Americans as well as Jews, Muslims, and queer people, all of whom are deemed sub-human and outside the spectrum of what it means to be American.

Dehumanization has long been part of the American story affecting historically marginalized people since the nation’s founding. Throughout his life, Malcolm X illuminated the disparities between these different Americas. As Malcolm X, he sought to center the stories of Black Americans and Black people around the world. As El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, he demanded recognition of the God-given dignity of all human beings. While El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz’s assassination at the age of 39 often overshadows the substance of his life, his religiously informed political agenda was based in the assumption that it is only when people respect each other’s humanity, only when people fulfill each other’s mutual rights, and only when people carry out equitable responsibilities toward each other, that “a society in which people can live like human beings on the basis of equality,” will be a reality. What Malik El-Shabazz sincerely wanted and worked tirelessly for was “nothing but freedom, justice, and equality, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all people.” His exhortation for connection with all people is in stark contrast to the brash advocacy for violence, particularly against white people, that is a common – and erroneous – depiction of his life and legacy.

Misunderstanding Malcolm X

The mischaracterization of Malik El-Shabazz as a provocateur of “hate to meet hate” and as someone who called for indiscriminate acts of aggression acts against white people is the outcome of several factors, and not simply because he was killed before he could realize the aims of his work. Too often, he has been dismissed by being placed in convenient juxtaposition to his contemporary, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., rather than regarded singularly and in his full complexity. Moreover, while some of the milestones of his life are well-known, including the six-and-a-half years he spent in prison for robbery, what is less examined is the influence of his parents on his mission to link the civil rights of Black Americans to the human rights of Black people around the world. Both his mother and father were supporters of Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican activist who advocated for pan-Africanism, which is the unification of people on the African continent with the African Diaspora. Moreover, scant context has been provided for his religious beliefs that undergirded his work, including the establishment of Black-centered institutions and what he called “the hypocrisy of democracy,” based on how Black people have been treated in America.

As with much of the public’s misunderstandings about Garvey, far too many people have a skewed vision of Malcolm X as an inciter of violence. His ideas have commonly been reduced to sound bites. When asked in January 1965 on The Pierre Berton Show whether he condones violence, he was clear that he did not. However, he did say that “the Black man in the United States and any human being anywhere is well within his right to do whatever is necessary by any means necessary to protect his life and property especially in a country where the federal government itself has proven that it is unwilling or unable to protect the lives and property of those beings.” Here, he was calling attention to the double standard that white people could defend themselves, while Black Americans could not without fear of appearing irrationally angry and inherently violent.

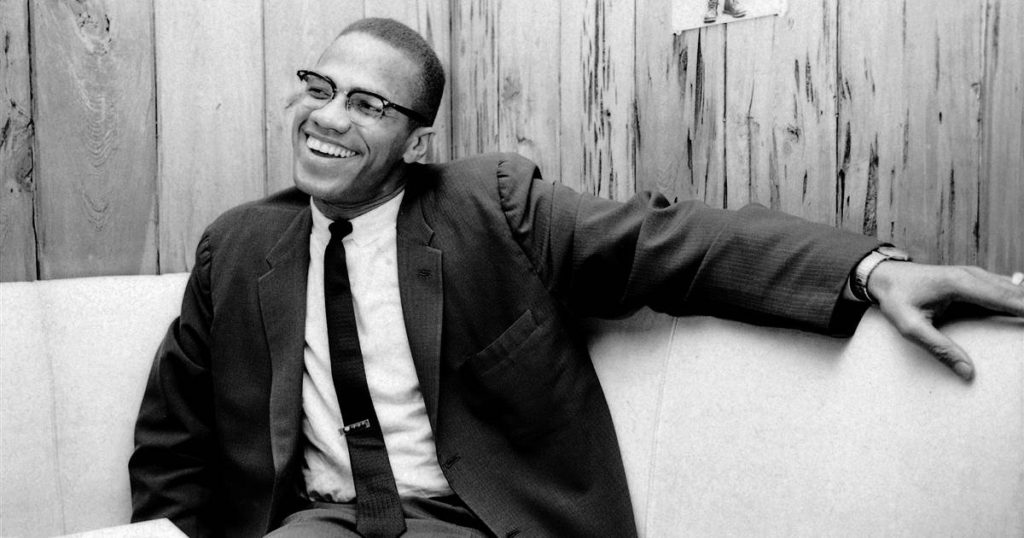

Malcolm X in 1964 (Photo: Truman Moore for Getty Images)

Similar misinterpretations existed during his lifetime. Astutely aware of the conflicting interpretations people had of him, he once commented, “For the Muslims, I’m too worldly. For other groups, I’m too religious. For militants, I’m too moderate. For moderates, I’m too militant. I feel like I’m on a tightrope.” In life and in death, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz has been considered a Black revolutionary. A human rights vanguard. An iconoclast. A political dissident. A statesman. A Sunni Muslim. A husband. A father. A brother. A human being. His self-described search for truth led him through several transformations, often marked by changes in his name. He went from Malcolm Little to his adopted nickname Detroit Red to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. “El-Hajj” is the honorific bestowed upon people who complete the Islamic pilgrimage. “Malik El-Shabazz” signaled both his embrace of Sunni Islam and his break with the Nation of Islam, an organization to which he had dedicated twelve years of his life. It is in this last iteration, as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, where we can best understand Malcolm X. His ideas and activism during this period reflect his identities as a Sunni Muslim and as a Black man and as a human rights activist and as a statesman and as a husband, father, brother, and son.

The Hajj and the Human Family

On April 20, 1964, during the five-day Hajj, Malcolm X wrote a letter to a friend from Saudi Arabia describing his new worldview. For perhaps the first time in his life, soon-to-be-El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz regarded “every human being as a human being – neither white, black, brown, or red” as part of the “Human Family.” Sunni Islam did not share what he described as the Nation of Islam’s “strait-jacketed world” of white people as devils, but “already molded people of all colors into one vast family.” Witnessing the confluence of Muslims around the world during the Hajj, he began to internalize the Islamic concept of umma, or a singular community of believers, originating from the Arabic root for “mother.” As he and Alex Haley wrote in his autobiography, “Everything about the pilgrimage accented the Oneness of Man under God.” From this perspective, because God is One, so, too, is humanity one entity. After the Hajj, he felt that skin color was no longer a valid lens by which to judge people. Rather, a person should be judged by deeds and conscious behavior, and ultimately it is one’s intentions that God will judge.

One month after the Hajj, he wrote in a letter that Islam compels one “to take a stand on the side of those whose human rights are being violated, no matter what the religious persuasion of the victims is. Islam is a religion which concerns itself with the human rights of all mankind, despite race, color, or creed. It recognizes all (everyone) as part of one human family.” He wrote that letter in Nigeria as he traveled the African continent to meet with political leaders. As he wrote from Ghana during the same tour, his desire for the political, cultural, and economic harmony “between the Africans of the West and the Africans of the fatherland” of all religions was not antithetical to his practice of Islam, but because of it. The interlocking inequities of Black people, Muslims and non-Muslims, were religious obligations to address.

The OAAU and the Human Problem

In order to extricate Black people from the oppressive power dynamics of white institutions, Malik El-Shabazz established the secular Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) a few months after the Hajj in 1964. He founded the organization to address Black unemployment, unlivable housing conditions, voter suppression, and to “decolonize” education curricula and the media. The OAAU was patterned in “letter and spirit” after the Organization of African Unity (OAU), an organization established in 1963 to eradicate colonialism and create political and economic ties across the African continent.

Malik El-Shabazz’s newfound belief in Sunni Islam compelled him to encourage other Black people, of all religious backgrounds, to stand up not only for their civil rights, but to join together in demanding their human rights. Domestically, the mission of the OAAU was to reconnect Black Americans with their African heritage, establish economic independence, and promote Black self-determination in order for Black people to have the access, benefits, and opportunities like their white counterparts. The OAAU worked for Black self-empowerment, self-defence, as well as political engagement – particularly voter registration and education. The OAAU also sought to bring charges against the U.S. government before the United Nations in violation of the human rights of the 22 million Black Americans.

Malik El-Shabazz’s experiences with Sunni Islam also changed his views on women’s role in organizational leadership. After the Hajj, he insisted that women were integral to the enlightenment and progression of any nation. The centrality of women in leadership positions within the OAAU was thus purposeful and included his wife Betty, his sister Ella Collins, acting chair Lynne Shifflett, Sara Mitchell, and Gloria Richardson. Indeed, these women ensured the OAAU continued after his death.

The ethos and scope of the OAAU reflected El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz’s post-Hajj shift from civil rights to human rights, from a singular focus on anti-Black racism to solidarity with every person who is targeted because of their skin color and physical appearance. This is evidenced by the links he forged with leaders of non-Black marginalized communities including Asians and Asian Americans, such as Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American civil rights activist who befriended Malik El-Shabazz’s in 1963 and who was present at the Audubon Ballroom when he was murdered.

During his final public talk, three days before his death on February 18, 1965 at Barnard College in New York City, Malik El-Shabazz articulated his global vision of solidarity: “It is incorrect to classify the revolt of the Negro as simply a racial conflict of black against white or as a purely American problem. Rather, we are today seeing global rebellion of the oppression against the oppressor, the exploited against the exploiter. We are interested in practicing brotherhood with anyone really interested in living according to it.”

For Malik El-Shabazz, everyone is connected through what he called the “Human Family” and is therefore is obligated to correct the “Human Problem” of racism. The sole formula to address the oppression faced by various constituencies of the Human Family consists of “real meaningful actions, sincerely motivated by a deep sense of humanism and moral responsibility.” Malik El-Shabazz believed white people must exercise their privilege as allies by becoming “less vocal and more active against racism of their fellow whites.” Simultaneously, leaders within communities of color “must make their own people see that with equal rights also go equal responsibilities.” He also presciently called out what would be the riots in Black-majority cities across the 1960s that led to the 1968 Kerner Commission, protested the Vietnam War, and sought ties with the Reverend Dr. Marti Luther King, Jr. especially to promote voting rights.

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz’s Message for Today

Malik El-Shabazz’s message remains controversial because it calls for a revolution where skin color equity and justice will exist. As he wrote for the Egyptian Gazette in August 1964, “Once we have more knowledge (light) about each other we will stop condemning each other and a united front will be brought about … We need more light about each other. Light creates understanding, understanding creates love, love creates patience, and patience creates unity.”

Sadly, today, almost six decades after his death, the right for people of color to exist equally and equitably with white people is still not recognized. The quest of the man who became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, and indeed the moral quest of each of us, is to respect and uplift, rather than dismiss and deny, each other’s humanness. Though there are differences in how to achieve this aim, Malcolm X as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz illuminated the path on which we must forge ahead as one human family if we are to change what he called “this miserable condition that exists on this earth.”

Dr. Sara Kamali is the author of Homegrown Hate: Why White Nationalists and Militant Islamists Are Waging War against the United States (University of California Press, 2021) and a Sacred Writes/Revealer Writing Fellow. You can subscribe to her newsletter through her website to receive updates and other writings every month, and follow her on Twitter @sarakamali.

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.