Making Marginalized History Mainstream: Collecting and Sharing South Asian Stories

Through social media, podcasts, and websites, South Asian Americans are claiming their place in U.S. history

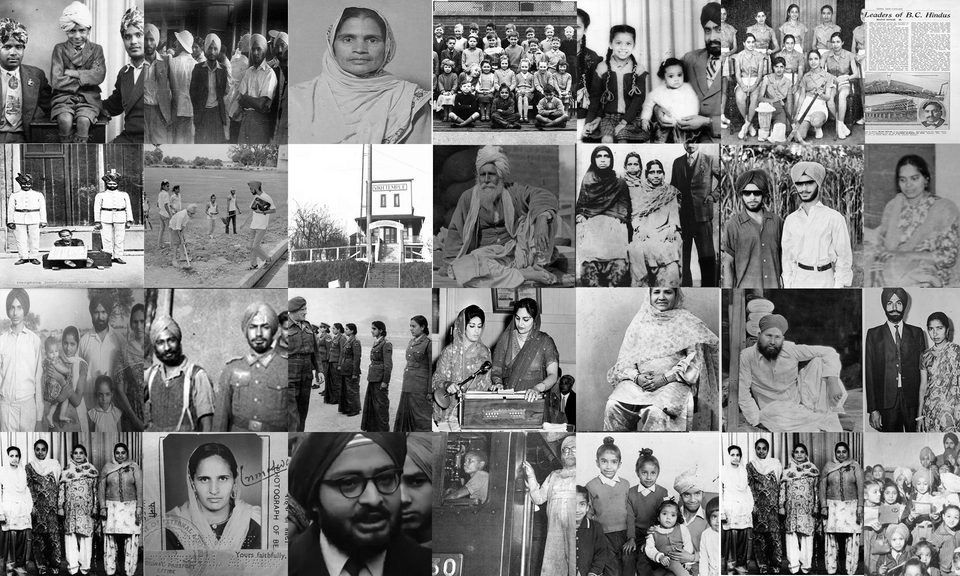

(Image source: Twitter header for @sikharchive)

Dalip Singh Saund migrated from the Indian subcontinent to the United States after completing his undergraduate degree in mathematics. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in the same field from the University of California, Berkeley in 1924. For two years, Saund looked for teaching jobs. Despite his qualifications, Saund’s prospects were grim. He was not a U.S. citizen and could not expect to become one in the near future.

In 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that Indians could not be naturalized as citizens because they were not white. Bhagat Singh Thind, one of the earliest migrants from South Asia, arrived in the United States in 1913. Thind became involved with the Ghadar Party, an organization founded by expatriate Indians to overthrow British rule in the Indian subcontinent, before enlisting in the U.S. Army. After six months of service, he applied for naturalization in Portland, Oregon. Though the examiner questioned his loyalty to the nation, Judge Charles E. Wolverton believed that Thind had demonstrated patriotism and granted him citizenship in 1920. However, the Departments of Labor and Justice advised the U.S. attorney in Portland to file a lawsuit to cancel Thind’s citizenship. The ruling of this now-famous case revoked Thind’s citizenship and led the Justice Department to extend the ruling to all Indians who had been naturalized. Indians remained ineligible for U.S. citizenship until 1946.

With no hope for citizenship, Indians like Dalip Singh Saund faced limited employment opportunities. After failing to secure a teaching position, Saund moved to Southern California in 1926 and began his life as a farmer. He spent his free time nurturing his interest in politics. Shortly after Congress passed the Luce Celler Act of 1946, which allowed Indians to immigrate to the U.S. and become naturalized, Saund became a citizen. He then embarked on his dream to become a politician. He began by serving his county in the office of judge of the justice court, then as county chairman of the Democratic Central Committee, and finally as the Democratic nominee for Congress. In 1956, Saund became the first South Asian American elected to the Congress of the United States.

***

Growing up in New York City in the 1980s and 1990s, I often heard my parents tell stories about how they migrated to the United States. They came here with only eight dollars in their pockets, found employment at fast-food restaurants and as newspaper delivery people, and experienced racism in the workplace for wearing forehead marks, or chandlos. In school, I learned about the early history of the United States, slavery, and the wars the U.S. fought. But I never learned the stories of Thind and Saund in school. In fact, I never learned anything about South Asians. Not much has changed in the decades since I was in grade school.

But recently, organizations and individuals are working to bring South Asian histories to light by documenting stories of South Asians in America through social media accounts, websites, and podcasts. These platforms have become forerunners in documenting the histories of people who trace their origins to Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Their projects demonstrate that South Asian histories are American histories; and consequently, histories of the United States are incomplete without the stories of South Asians and their contributions to the nation.

Our Stories

Efforts to reclaim South Asian histories often begin with individuals who want to learn more about their cultures, traditions, and backgrounds. One such effort is led by Samip Mallick, a second generation South Asian American, who founded the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). The non-profit organization is committed to creating an inclusive society by documenting, preserving, and sharing stories of South Asian Americans. SAADA’s early endeavors like the First Days Project invited people to collect and share photos and memories of their immigrant experiences. In July 2021, SAADA published a collection of those narratives in the book Our Stories: An Introduction to South Asian America.

(Our Stories book. Image source: saada.org)

Our Stories tells the history of the United States through the voices of South Asians. It draws particular attention to people who identify as working class, undocumented, LGBTQ+, Dalit, and Indo-Caribbean to highlight varied South Asian American experiences. Stories of people like “Sherry Singh,” who traveled from Guyana via the “backtrack” to the United States in 1996, present the multi-layered challenges that some face in establishing themselves here. Since childhood, Singh dreamt of becoming a lawyer, a profession not open to her because she did not have a social security number. But with the passing of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2012, “Sherry Singh,” along with 800,000 others, became eligible for a social security number, a driver’s license, and a work permit. Today, “Sherry Singh” works as a public school aide in Queens, New York.

The book also examines the lives of South Asians like Bhagat Singh Thind and Dalip Singh Saund before and after pivotal moments in the country’s history. It discusses the contributions South Asian Americans have made over the last half-century in the arts, religion, and civic engagement. Contributions include literary works by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri and the sacralizing of the American religious landscape through the construction of mosques, temples, and gurdwaras. And the book connects the past to the present by describing how Dalip Singh Saund paved the way for other South Asian Americans, such as Ro Khanna, Pramila Jayapal, Raja Krishnamoorthi, and Ami Bera to hold prominent positions in Congress today.

Stories on Social Media

In the last five years, South Asians outside of formal organizations like SAADA have used social media to collect, preserve, and share our histories. Several popular Instagram and Twitter handles such as @brownhistory, @Sikharchive, and @Hindoohistory make histories of South Asians within and outside the United States publicly available. By featuring stories on social media, these projects meet many second and third-generation South Asians where they are – online. Social media posts, which usually include small images and short captions, provide followers with a starting point for studying important figures and their contributions to history, as well as documenting, preserving, and sharing their own family histories.

Created in 2019 by Ahsun Zafar, an electrical engineer in Canada, @brownhistory is a crowd-sourced digital archive with 1,800 posts and over 500,000 followers. Zafar’s Instagram account emerged from his interest in learning more about his background. Whereas Our Stories discusses the history of South Asians chronologically, @brownhistory adopts a more social strategy by posting excerpts of personal stories and interspersing those with narratives about the history, culture, and practices in South Asia. Posts often include stories of aristocrats, families, interreligious marriages, and the partition of India and Pakistan as retold by the descendants of those who witnessed these events. For example, a post about Princess Catherine Duleep Singh, the second daughter of Maharajah Duleep Singh of Lahore, describes her advocacy for women’s voting rights and her efforts to save the lives of Jewish families in Nazi Germany. Other posts begin with statements like, “…My late Grandfather’s parents…,” “…A sample from Dad’s record collection…,” and “…My father is a Bangladeshi Buddhist…,” and introduce family histories with photographs and personal narratives.

Part of @brownhistory’s mission involves centering the voices of women and illustrating how women-led movements brought attention to pressing social issues. For example, one post describes Asha Puthli, a prominent singer-songwriter and actress, who addressed climate change when she released “Chipko Chipko,” a cover of “Smooth Criminal” inspired by the Chipko Andolan, a tree-protecting movement initiated by rural women in Uttarakhand to prevent deforestation. Other South Asian women profiled on the account include those who protested outside of the United States Embassy in Delhi (1971) to demand the release of civil rights activist Angela Davis, and the women who became known as the “Sari Squad” (1984) for protesting against the deportations of South Asians in the United Kingdom.

(Image: photo of the “Sari Squad.” Photo source unknown)

Throughout @brownhistory, Zafar cites sources such as news media, academic studies, and personal stories in an attempt to equalize history-writing practices. Histories are often written by individuals in power. Zafar aims to rewrite history, labeling his account as “South Asian history retold by the Vanquished.” He reworks Winston Churchill’s famous saying, “History is written by the victors,” to highlight the benefits of writing histories from the bottom-up. He concludes most posts with a familiar request, “DM me your stories!” to add to this growing archive. And while people of lower socio-economic status without internet access are excluded from these conversations, for those who can access social media, @brownhistory raises awareness about South Asians’ historical worldwide contributions.

The desire to recover less commonly known histories underpins the work of @Hindoohistory and @Sikharchive. @Hindoohistory is an Instagram and Twitter handle maintained by attorney Vishal Ganesan that reports on American representations of Hindu traditions in news media. The term “Hindoo” was employed by British colonialists to refer to the people residing in the Indian subcontinent, thereby conflating religion and geography and obfuscating the differences between Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Hindus, and others. In the United States, the term “Hindoo,” often found in eighteenth and nineteenth-century news media, cemented differences between practitioners of Hindu traditions and Christians. The @Hindoohistory accounts appeal to those who want to learn more about how Hindu traditions developed in the United States and how Christian Americans reacted to them. Ganesan tweets stories of news clippings such as “Heathen Invasion,” that warns readers of how women are being spiritually corrupted by their irresistible attraction to “heathen propaganda” and their “embrac[e of] its strange mysteries.” Twentieth-century news media often depicted Hindu traditions as mysterious, exotic, fearsome, and not suitable in the United States. Largely absent from Ganesan’s project are the voices of Hindus themselves like Swami Vivekananda and Paramhansa Yogananada, who wrote or delivered speeches on Hindu traditions throughout the United States, as well as Hindu organizations that published pamphlets, newsletters, and magazines for their followers.

Similar projects to reclaim South Asian ethnic and religious histories, using different mediums, are developing in various parts of the world. Sukhraj Singh, a British Sikh who resides in Denmark, began his podcast @Sikharchive in 2020 with the intent of documenting the rich histories of Sikhs in Copenhagen. Since then, his podcast has evolved to include episodes from a range of experts, historians, and journalists on Sikh and Punjabi history. Like @brownhistory and @Hindoohistory, @Sikharchive shares a commitment to using personal stories and information from academics and news media to raise awareness among South Asians about their histories.

Reclaiming Histories

SAADA, @brownhistory, @Hindoohistory, and @Sikharchive are participating in a wave of grassroots efforts to create self-histories of South Asians within and beyond the United States. Each project emerged, in part, as a personal journey, stemming from a desire to learn more about one’s own history, culture, religious traditions, and background. The founders’ journeys sought to fill gaps in their own knowledge of South Asian history – gaps often created by a lack of representation of South Asians in educational curriculums, incomplete accounts of family histories, and distance from their ancestral homes. The stories they have uncovered and the histories they have constructed are continually made available on public platforms. And since most history textbooks in the United States still do not showcase our rich history, these media platforms signal the urgency of preserving stories of South Asian people, communities, and religious traditions that would otherwise be lost with the passage of time.

Bhakti Mamtora is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at the College of Wooster and a Sacred Writes/Revealer Writing Fellow. Her research examines orality, textuality, and canonization in transnational Hindu traditions.

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.