Making Good Jewish Trouble

A review of Sandi DuBowski’s documentary "Sabbath Queen"

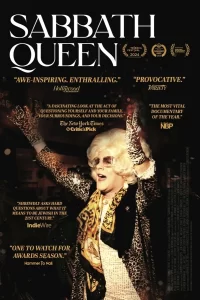

(Image: Rabbi Amichai Lau Lavie. Source: Rialto Cinemas)

Director Sandi DuBowski makes movies into social movements. His 2001 documentary Trembling Before G-d illuminates the struggles and courage of queer Orthodox Jews. When DuBowski took Trembling on the exhibition road, he was determined to have the film be a catalyst for religious activism. Rabbis whose intolerance had harmed people featured in the film appeared on stage to apologize for their spiritually-inspired cruelty and to invite Jewish queer folk to share a Shabbat table with them. The film became a touchstone for queer Jews who took to calling themselves “tremblers.” It helped catapult the Conservative movement, which had been wrestling mightily with queer issues, to a position of greater tolerance, including the ordination of queer rabbis. And it inspired other faith communities to do their own repentance for religious homophobia. A screening in Salt Lake City literally brought Mormons out of the closet to express their pain and their queer persistence to their co-religionists.

DuBowski is back to making cinematic good trouble with his 2024 documentary Sabbath Queen. This sprawling film follows Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie, the spiritual co-leader of New York’s God-optional Lab/Shul and his Hasidic drag queen persona, Rebbitzin Hadassah Gross. Lau-Lavie grew up in Israel, the heir apparent of 29 generations of Orthodox rabbis. Involuntarily outed by a journalist when he was in his 20s, Lau-Lavie has spent his spiritual life wrestling with his Orthodox patriarchal legacy while striving to bring Judaism into the 21st Century. As he puts it, “Not everything we’ve inherited is worthy of being passed on.” But determined to separate the wheat from the chaff and to honor the Jewish queer, the feminine principle, and interfaith love, Lau-Lavie makes his lifework an amalgam of spiritual work and play. Director Sandi DuBowski chronicles Amichai’s spiritual journey onscreen. And as Sabbath Queen makes its way across the world at film festivals and in theaters, DuBowski and Lau-Lavie often accompany it and turn screenings into temples full of soulful energy.

The origin story of this documentary hearkens back to Trembling Before G-d. DuBowski originally wanted to include Lau-Lavie’s queer Orthodox journey in Trembling; Lau-Lavie refused, but they became friends. The making of Trembling caused DuBowski to take an Orthodox turn in his own Jewish orientation. However, after completing that film, he found himself becoming religiously restive with Orthodoxy and attracted to the less traditional Jewish journey that Amichai was on. Given that Amichai “opened [him] up to explore Judaism in a different way,” he committed himself to let Amichai’s “life unfold before the camera.”

With 1,800 hours of footage of that life as well as 1,100 hours of archival footage, the film took over 21 years to make, with six of them devoted to editing. The working title of the film was “Rabbi,” and one could well imagine the tagline “this is what a 21st-century rabbi looks like” accompanying the promotional picture of Lau-Lavie in a tight black tank top with tefillin (phylacteries) wrapped around his muscular arm. However, the title Sabbath Queen more aptly conveys the mixture of the sacred and the campy that defines Amichai’s Judaism.

Amichai’s spiritual awakening and desire to challenge his patriarchal legacy began in earnest in his teens when he was part of a mixed-gender group that went to the Kotel (also known as the Western Wall) in Jerusalem. Both the police and Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) men encircled the group and forcibly removed them. Girls “screaming and crying” as they were dragged away from this holy site haunted him, and he couldn’t wrap his mind around such violence directed at “Jews who want to pray.”

Given his early championing of gender equality as foundational to Judaism, it seems no coincidence that Amichai found his own voice as a queer Jew—and a spiritual leader—in drag as Rebbetzin Hadassah Gross. Living in New York in the late 1990s, he found a fusion of the queer and the spiritual in the Radical Faeries, a group that was, for him, full of “worship and laughter.” Serving as the Master of Ceremony at a Radical Faeries event and admittedly under the influence of “one vodka too many,” the idea for a widowed Hungarian Rebbetzin who spoke with a strong accent and was the mother of six sprung from his head “like Athena.” She embodied his conviction that “redemption will only come through transgression.” Rather than being a voice of antagonism, she was in favor of everything, was a star of Purim (a carnivalesque Jewish holiday), and preached that the “biggest commandment is to live happily.” Representing the divine feminine as well as the disruption of the masculine/feminine binary, the Rebbetzin allowed him to give voice to the “profound mystical teaching” that was within him and of which he was previously unaware. He ultimately came to understand her as “the mask” he wore to discover himself.

Given his early championing of gender equality as foundational to Judaism, it seems no coincidence that Amichai found his own voice as a queer Jew—and a spiritual leader—in drag as Rebbetzin Hadassah Gross. Living in New York in the late 1990s, he found a fusion of the queer and the spiritual in the Radical Faeries, a group that was, for him, full of “worship and laughter.” Serving as the Master of Ceremony at a Radical Faeries event and admittedly under the influence of “one vodka too many,” the idea for a widowed Hungarian Rebbetzin who spoke with a strong accent and was the mother of six sprung from his head “like Athena.” She embodied his conviction that “redemption will only come through transgression.” Rather than being a voice of antagonism, she was in favor of everything, was a star of Purim (a carnivalesque Jewish holiday), and preached that the “biggest commandment is to live happily.” Representing the divine feminine as well as the disruption of the masculine/feminine binary, the Rebbetzin allowed him to give voice to the “profound mystical teaching” that was within him and of which he was previously unaware. He ultimately came to understand her as “the mask” he wore to discover himself.

Once Amichai allowed himself to explore his spiritual options directly and unmasked, he retired the Rebbetzin Hadassah as his queer spiritual alter ego. However, worshiping the feminine aspect of the divine became central to the Lab/Shul experience in the form of welcoming the Sabbath Queen into that spiritual space every week (this ritual follows the kabbalistic tradition of imagining the Sabbath as a bride or a Queen). For Shira Kline, the co-founder of Lab/Shul and the queer daughter of a rabbi, bringing the Sabbath Queen into the Lab/Shul house served as an antidote to the Judaism of her youth. In that tradition, men read and led, and women watched. Rather than worshipping God as a masculine judge and king, Lab/Shul and the Sabbath Queen ritual connect her with “spirit and mystery, the feminine voice.”

DuBowski includes several takes of the raucous, joyous ritual in the film that bears its name. And screenings of the film often include a Sabbath Queen service so that audiences are not simply watching Amichai and his Jewish co-conspirators at spiritual work, but embodying and performing that work themselves. In this way, DuBowski hopes that Sabbath Queen, like Trembling Before G-d, might be a film that becomes a catalyst for change, a movie that turns into a movement for a more joyful and inclusive Judaism.

To further emphasize and represent the centrality and necessity of feminine spiritual energy, DuBowski crosscuts the Sabbath Queen ritual at Lab/Shul with an animated version of Rebbetzin Hadassah walking into the Dead Sea to release the Shekhinah (the feminine aspect of God in the Jewish tradition) from her burial ground. Brilliantly, this onscreen anti-realist spiritual work is given the imprimatur of noted Israeli professor and feminist activist Alice Shalvi, who died in 2023. Shalvi says in the film that, historically, the Shekhinah was perceived as a threat to patriarchy and thus had to be sidelined. By incorporating an animated form of Rebbetzin Hadassah into the film, DuBowski conveys the playfulness that attends Amichai’s and Lab/Shul’s serious commitments to a queer and feminist Judaism.

Amichai was well into his work as the co-leader of Lab/Shul when he decided to pursue a rabbinical degree at the Conservative Movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS). DuBowski conveys the irony of this new direction by twice including footage of Napthali Lau-Lavie, Amichai’s father, saying that he couldn’t imagine his son ever becoming a rabbi. While his father couldn’t see his wayward son taking his place in the family business, Amichai’s Lab/ Shul congregants were also flummoxed by his desire to formally become part of the rabbinate. He undertook this path because he believed that to “make real change,” you have to “get inside the system.” Unable to situate himself within Orthodoxy, he also couldn’t pursue a more liberal rabbinical route since he felt that “would shut the doors of dialogue with more right-wing religious Jews,” including members of his own family. His time at JTS was exhausting; while the institution was committed to normative Jewish practice, Lau-Lavie was committed to transgressive Judaism. Footage of Rabbi Daniel Nevins, then dean of JTS, learning that Lau-Lavie leads a God-optional congregation underscores that JTS and Amichai continually tested and challenged one another. Despite those challenges, Amichai completed his degree and was ordained as a Conservative rabbi.

But intermarriage caused Amichai and Conservative Judaism to part ways. The Conservative movement does not allow its rabbis to officiate at interfaith weddings. Amichai knew this when he enrolled at JTS, and the scene when he explains this to his perplexed and disappointed Lab/Shul congregation is poignant. However, after being ordained, he felt the need to serve a queer couple who wanted a Jewish-Buddhist marriage ceremony. Footage from this event opens the film; later, we return to it, with a fuller understanding of this pivotal moment in the life of this couple, in the Lab/Shul community, and in Lau-Lavie’s rabbinical career. Having broken Jewish law, he resigns from the Rabbinical Assembly of the Conservative Movement, though he retains the title of rabbi. DuBowski cleverly cross-cuts the rabbinical backlash to this event and the first dance of these newly married “Joys,” those who understand themselves as both Jew and Goy.

The perspective of Rabbi Benny Lau, Amichai’s brother and a popular and prominent Israeli rabbi, is threaded throughout the film. Unsurprisingly, he is a cautionary voice about Amichai’s spiritual ways and waywardness. For Benny, “playing a game with Judaism,” is full of danger and creates a crisis of boundaries, whereas for Amichai, the transgression of boundaries is a spiritual opportunity and even a necessity. At one point, Benny urges care because “people learn from you.” Yet, despite his commitments to Orthodox traditions that Amichai upends, he becomes Amichai’s student. He celebrates Amichai’s ordination as a rabbi in the Conservative movement, recognizes that “the closet is death,” and ends up doing his own feminist work by bringing a woman as a spiritual leader into his own traditional community. Such incremental but nonetheless transformational changes to Benny’s own spiritual orientation confirm Amichai’s role as a cross-denominational changemaker. But Benny’s shifts simultaneously point to the power and the possibility of religious wrestling matches that regularly happen in even the most staunchly tradition-bound communities. Like Trembling Before G-d, Sabbath Queen explores fault lines across Jewish worlds and the pain visited on those who are Jewishly othered. Yet, both films demonstrate that throwing out the baby with the bathwater is as untenable and counterproductive as settling for the status quo.

Amichai’s spiritual orientation is one that resists the binary of observant and secular Jew, that transgresses the boundary between masculinity and femininity, that challenges those who would legislate love and separate Jew from Gentile in intimate relationships. Given this penchant for binary busting, Amichai unsurprisingly refuses to accept the opposition between Palestinian and Israeli. During the 2014 Gaza war, he attended a pro-Israel event sporting a sign that read “Stand with Israel, Mourn with Gaza, Cease the Fire, Seize Our Peace.” When he is aggressively told that he is in the wrong place and that he is a mamzer (illegitimate), he refuses such a summary dismissal, telling his verbal attacker that his father was a Holocaust survivor, that he served in the IDF, and that he is a Hebrew speaker.

His response to October 7 closes the film. After Hamas’s contemporary pogrom, he went to Jerusalem, “hold[ing] the pain of my Israeli family” while not justifying the destruction of Palestinian life in Gaza. Insisting on a “bilateral ceasefire, a hostage deal, and a path toward permanent peace,” he insists that the need to “reimagine our sacred traditions to achieve peace” is the “challenge of our lifetime.”

While Amichai is full of spiritual chutzpah, he is simultaneously spiritually humble. Admitting to doubts about the path he is on, he says “I think I’m doing the right thing, sometimes I’m not sure, only time will tell.” Recognizing that his choices might foster continuity or “disrupt [it] too radically,” he refuses dogmatism as he continues to serve his congregation. Amichai does what Jews perhaps do best: he wrestles.

Helene Meyers is Professor Emerita of English at Southwestern University. Her most recent book is Movie-Made Jews: An American Tradition.