Just The Right Amount of Sugar

A review of the documentary Making Sweet Tea and its portrayal of Black gay men in the South and their relationship with religion

A scene from the documentary film, Making Sweat Tea

When I first watched Trembling Before God, the powerful 2001 documentary about gay and lesbian Orthodox Jews, I did not understand why people worked so hard to stay in a community that rejected them. In a way, that’s the premise of the film, and the space between the question and the answer is kind of the point. But for me, it left an unresolved ache, a confusion, and, as an observant Jew, a sense of shame: how could I live with this community that was, for so many, unlivable?

Making Sweet Tea, the stunning 2019 documentary about Southern gay Black men directed by University of Pennsylvania’s Dean of the Annenberg School for Communication John L. Jackson, leaves no such lingering doubts or confusion about why some queer people stay in communities that do not embrace them. The simple answer, the reason they stay, is that for the men of Making Sweet Tea who generously invite viewers into their lives, the South is home.

The film draws its inspiration from E. Patrick Johnson’s 2008 book Sweet Tea, which he later turned into a one-man show. Johnson, himself gay and Black, serves as the documentary’s host, interviewer, and as the conduit for the film’s prime subject. While Making Sweet Tea takes an in-depth look at several gay Black men in the South, it is centrally about Johnson’s own journey: telling the stories of others, but being one of the stories as well. It examines what it means to tell those stories, and how telling them not only bears witness but validates: I see you, and you have a right to be. I hear you, and you have a right to tell. It is also the story of Johnson’s mother, the (late) Mama Sarah, whom we visit in Hickory, North Carolina, on the Black (south) side of the tracks in the one-bedroom home he shared with her and six siblings. It is the story of his partner Stephen, who is also an editor on this project. It is the story of E. Patrick’s losses and loves: his friend Reggie who died of AIDS; his pain when his mother would not, at first, acknowledge Stephen as his partner; his own journey from a heteronormative life of Black respectability politics to embracing and celebrating his identity.

The film draws its inspiration from E. Patrick Johnson’s 2008 book Sweet Tea, which he later turned into a one-man show. Johnson, himself gay and Black, serves as the documentary’s host, interviewer, and as the conduit for the film’s prime subject. While Making Sweet Tea takes an in-depth look at several gay Black men in the South, it is centrally about Johnson’s own journey: telling the stories of others, but being one of the stories as well. It examines what it means to tell those stories, and how telling them not only bears witness but validates: I see you, and you have a right to be. I hear you, and you have a right to tell. It is also the story of Johnson’s mother, the (late) Mama Sarah, whom we visit in Hickory, North Carolina, on the Black (south) side of the tracks in the one-bedroom home he shared with her and six siblings. It is the story of his partner Stephen, who is also an editor on this project. It is the story of E. Patrick’s losses and loves: his friend Reggie who died of AIDS; his pain when his mother would not, at first, acknowledge Stephen as his partner; his own journey from a heteronormative life of Black respectability politics to embracing and celebrating his identity.

The documentary follows Johnson in his encounters with many of the subjects from Sweet Tea, using scenes from his stage show as well as interviews to follow up on their stories. But there was one story Johnson hadn’t examined in the book: his own. The film explores Johnson’s recognition that to stand witness to the lives of others, he must stand witness to his own. And to do that, Johnson must go home.

The film opens with a shot of trees. Highway signs. A moving car. Johnson’s hand, with a ring on it (a wedding ring?), on the steering wheel. Johnson is going back to where he came from, to Hickory, North Carolina. (It’s not subtle: strains of “I’m Going Home” provide the background music.) Johnson looks resolute. A little nervous. He’s been telling the stories of gay Black men for years. But now his life, his birth home, and his family are part of the story. We see the house he grew up in. We meet his mother, the magisterial Mama Sarah. They make tea. It’s a whole ritual: the boiling of the water, the selection of the bags, the ice cubes, the sugar, the pitcher, and glasses. Maybe some lemon.

And then, once the tea is made, we will hear the stories. The tea, we learn, is the story. The gossip. The narrative. The tea is shared — or, salaciously, spilled — over tea. It’s an important Southern ritual and one the men featured in the film, who are so often excluded from other rituals of Southern life, embrace and share. Johnson and his mother stand in the family kitchen and carefully make the tea so the audience can share in the experience with them.

But then we don’t. Instead, the film cuts to three of the men who will be key characters in the documentary: Charles, Duncan, and Shean. They explain that the tea is not just a beverage but a narrative, priming us to hear their stories. And then the film cuts to Johnson, walking on the railroad tracks that divide Hickory. He, like other Black residents of the town, comes from the wrong side. But he made good. The first African-American man from Hickory to earn a Ph.D. (and have a day named for him!), Johnson has always been keenly aware of what he means to his community. He also always knew he was gay, but, as he says in the film, that was wrong in the eyes of his community. So he “overcompensated.” He sent money home. He was a model son. He never did drugs. He tried to inspire others so that, when he did come out to his family, he wouldn’t be a disappointment. As he says it, we see Johnson reflecting on the man he once was, deeply engaged in Black respectability politics, and the man he is now, telling the stories of other Black queer men who — like him — are proud of who they have become, and are proud of the histories and places that have brought them here.

Johnson came out many years ago, and his mother walked him down the aisle when he married his partner, as we see in the documentary footage. But, in many ways, this film is his coming out. Because for Johnson coming out is also a way of coming home. This film illuminates how Johnson and the men he interviews found ways to make the South home.

E. Patrick Johnson in his hometown of Hickory, North Carolina

Being Black in the South has its own history of hardness, of danger, of violence, of sadness and loss. As one interviewee, Freddie, puts it, “This is still the South. People don’t like Black people period. But then to be a gay man?” We know how that sentence finishes. But this film is not an 80-minute chronicle of danger, sadness, and loss. All of these are present: it’s a fact of life, of these lives. But this is instead a film about community, and connections, and love. These stories matter because they haven’t been told before Johnson collected them. But they also matter because, as the film demonstrates, storytelling itself is part of Southern culture. These men, in telling their stories to Johnson, and to us, are asserting their identities, insisting on their Southernness, their Blackness, and their gayness. And insisting on the dignity that comes by telling their own stories. While we hear about racism and homophobia, we also bear witness to the lives the men have built. Good lives. Lives like Harold’s, who is celebrating 50 years with his partner. They do the crossword together every morning. They were finally able to wed in 2015, and when I saw their wedding picture, I cried.

This film puts Johnson back in direct conversation with some of his subjects to archive and embody their stories. Director John L. Jackson Jr. is playful with the concept of media itself, using the camera to capture Johnson rehearsing the one-man show. We have the uncanny privilege of seeing Johnson perform his subject Charles in clips of play practice, and then later meeting Charles himself. And we even, in one of the film’s most magical moments, get to witness Charles see himself through Johnson’s eyes as he watches the performance for the first time. Charles is shook. He cries. Because E. Patrick Johnson is good — his cadences, the way he inhabits his body as their bodies, his expressions and gestures. His singing! And Johnson is generous; his interpretations of these men are a way to honor them. It’s a way to appreciate these lives, in their richness and complication and depth.

And to do that, we have to travel. Because we can’t understand who they are without visiting where they are. The South, yes, but also the church, and the high school, and the beauty salon. It’s Charles’ beauty salon, and it is there that Johnson provides one of the most searing interviews of the film. Like his interviewer, Charles is from Hickory. In a twist, however, Charles had been Johnson’s role model. When Johnson first interviewed Charles for the book, Charles was totally out to Hickory; Johnson was not. Johnson, as he shares, was — then — too tied to the church, to notions of respectability, and to avoiding the condemnation that would be directed at him, to come out to the town that raised him. Unlike so many other gay men (including Johnson) who moved away from Hickory, Charles is still there. “I live here in spite of the odds,” he tells us. But Charles is celibate. He has abstained from sex for the past fifteen years in an attempt to make peace with his church, a place with heaven and hell and a God who has made clear that he abhors homosexual acts.

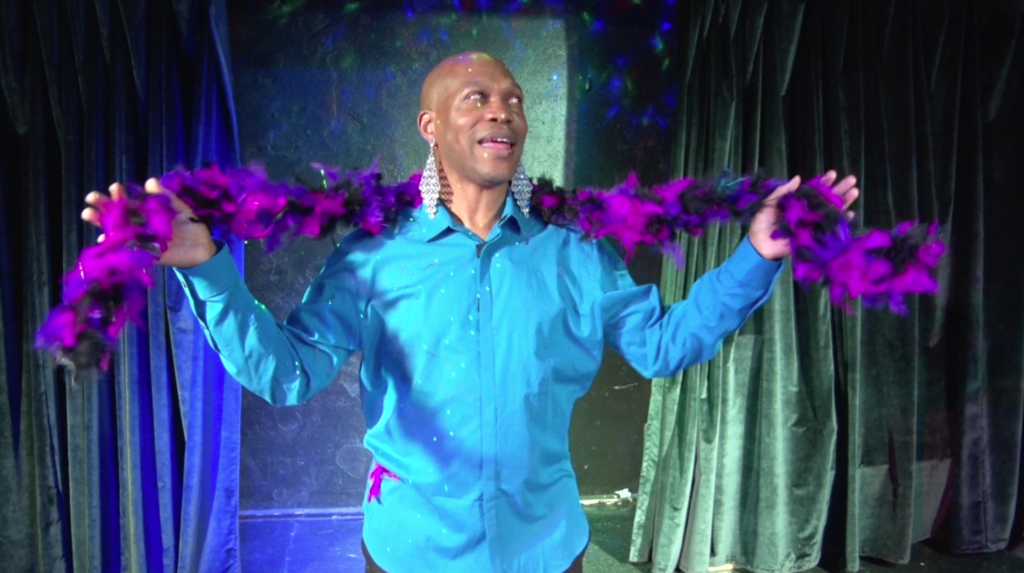

Charles, we learn, once performed as the drag queen Chastity, a part of himself he has left in the past. But Chastity comes back in Johnson’s show, and in the film. And Charles gets to see her one more time. He welcomes her back like an old friend, and we hear Charles insisting, in that moment, that “there is nothing wrong with Charles Kenneth Danner, Jr.” And though he doesn’t say it, it feels like an acknowledgement that there is also nothing wrong with Chastity — as performed by Johnson, and, maybe, as embodied by Charles as well.

Johnson performing as Chastity

Charles lost Chastity, but he kept his church. Johnson, it seems, has not. But we don’t fully know, because Johnson keeps his own relationship with religion obscure even as he explores its importance for others. That’s a clear line for him: he mentions the church as an entity, but then stops at specificity: no denominations are named. The church is such a central and powerful part of Black Southern identity and activism and experience and daily life. It is a central part of the lives of so many of the people we meet. But aside from the scenes with Charles and Duncan, we only view it from a distance and around the corners. We catch glimpses of it in Johnson’s church-trained singing voice, which betrays just a hint of sadness in those precious moments when we get to hear it. The choir, Johnson notes, was the one place he felt safe. But, he says, “the same religion that supports you is the same religion that damns you to hell.” Finding a home in that can be difficult. It can also be a reason to leave. But Johnson came back. To the South, to Hickory, and to the church. We are never told why: perhaps that will be the next film?

Another prominent figure in the film, Duncan, does talk about his religious background. He says, “Church didn’t play in my upbringing, it was my upbringing. When your father is the pastor, and the church is less than 200 people, that’s your extended family.” He found in the church all the love and admiration that was in other spaces denied to young Black men, and he found in the church gay men, the “flaming queens who ran the choir,” and “the bright, articulate young men” who made the institutions within the Black southern church possible. For Duncan, the church was a place where masculine expectations were quietly different, and he could be himself. While he does not say so explicitly, we understand that there were places in the church where Duncan felt comfortable, and people in the church — those queens and bright young men — whose queerness spoke to his own. We don’t know how Duncan’s journey affected his birth family or his church family, but we do know that his faith sustained. He is now an openly gay Unitarian Universalist minister who continues to foster his relationship with God and helps others do the same. It’s not the same church as that of his youth, but it is, for Duncan, the same God.

There’s wistfulness in these reflections, a sense of sadness and loss, and also strength: the church helped make these men, but it does not define them. In that way, perhaps, the church is different than the South, and different than being Black, and different than being gay. And different than telling stories, all of which proudly define the people in the film.

Including Johnson himself. He’s lived with these men and their stories for a long, long time: it took the process of making the film for him to turn his interviewer’s lens on to himself. And, generously, to invite us to listen. It is an act of breathtaking courage, to make oneself vulnerable, to consider one’s own life alongside the lives of those who have entrusted him so powerfully.

The story of gay Black men in the South is rich, and vibrant, and alive, and ongoing, and that’s the point. Johnson bears witness, and so do we, sharing in the Southern ritual of pouring tea and telling stories. But it is just the beginning: there is much left to explore, so many lives still to honor. So many losses to mourn, and so many others — including the church — that may yet be resolved. As Johnson reminds us, it all starts with acknowledging. With being present. In his own words: “People ask me all the time how did you get these men to open up to you, be honest about such personal stories, and I say . . . I asked.”

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Medical Ethics at Drexel University. You can find clips of her freelance writing at www.sharronapearl.com.