Introducing the Quran to Europeans: The Orientalism of Translation

The complicated history of Christians translating the Quran into European languages.

For a long time, I’d arrive early at the independent school where I taught humanities between stints in graduate school. If the roads threading the salt marshes of Massachusetts weren’t congested, I’d be the first to see the fluorescent lights of the faculty lounge flicker on, tentatively at first, illuminating a familiar landscape of tables, chairs, and bookcases. This congregating place provided a quiet oasis before the morning bell punctuated a crescendo of pacing students, clanging lockers, and flurried conversation.

The faculty lounge served as a depot for gifted supplies as well as a work space. As if by magic, shifting columns of National Geographics, or maps sallow with age might materialize. A discerning eye might salvage new classroom supplies from the neglected remnants of attics and basements.

One autumn morning, I found a pile of boxes neatly stacked on the shopworn table in the corner of the teacher’s lounge. Scrawled in a fading marker along the top was a label indicating the contents: “Books – Please Take!” Near the bottom of the first container, I excavated a handsome English-language Quran, its mustard folio lined with a filigree of sienna and turquoise. Knowing I’d be lecturing on Islam later that semester, I took it back to my classroom.

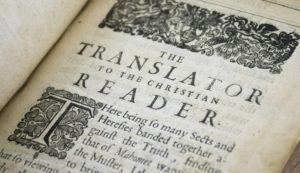

Paging through the volume, I encountered a publishing history alongside the usual introductory material. Intrigued, I read on. I soon discovered the first English-language translation of the Quran in the United States originated from a press within walking distance from my school. But what riveted my attention was the vitriolic preface from this American Quran, a reprint of the Alexander Ross’s 1649 translation from a French version:

“Good Reader, the Great Arabian Imposter now at last after a thousand years is by way of France arrived in England, and his Alcoran or Gallimaufry of Errors (a brat as deformed as the parent, and as full of heresies as his scald head was full of scurffe [sic]) hath learned to speak English. I suppose this piece is exposed by the Translator to the publicke view no otherwise than some monster brought out of Africa, for people to gaze, not to dote upon; and as the sight of a monster, or misshapen creature, should induce the beholder to praise God, Who hath not made him such; so should reading of this Alcoran excite in us both to bless God’s goodness toward us in this land, who injoy the glorious light of the Gospell, and behold the truth in the beauty of his Holinesse, who suffers so many Countreys to be blinded and inslaved with the misshapen issue of Mohamets braine…”

“Good Reader, the Great Arabian Imposter now at last after a thousand years is by way of France arrived in England, and his Alcoran or Gallimaufry of Errors (a brat as deformed as the parent, and as full of heresies as his scald head was full of scurffe [sic]) hath learned to speak English. I suppose this piece is exposed by the Translator to the publicke view no otherwise than some monster brought out of Africa, for people to gaze, not to dote upon; and as the sight of a monster, or misshapen creature, should induce the beholder to praise God, Who hath not made him such; so should reading of this Alcoran excite in us both to bless God’s goodness toward us in this land, who injoy the glorious light of the Gospell, and behold the truth in the beauty of his Holinesse, who suffers so many Countreys to be blinded and inslaved with the misshapen issue of Mohamets braine…”

Filled with slander, the preface conjured the ramblings of an Internet troll rather than the scholarly introductions one reads today. Ross’s “Needful Caveat” presents Islam as deviant and pernicious. Seemingly thinking that his translation would pose some danger to non-Muslim English readers, Ross suggests the value of this monstrosity lies in the contrasts it illuminates. “The glorious light of the Gospell” shines brighter against the darkness of Islam. The translator therefore summons his audience to “praise” and “bless” God for this token of the “obscurity and bondage” from which they have been liberated.

This translator’s preface to the Quran represents a single specimen of a genre that flourished for centuries. For a Quran to appear in Europe and North America without an admonition on the dangers of misuse was long unthinkable. Such introductions to printed translations veer between fascination and hostility toward their subject, but invariably end by disparaging it. At the same time, the dissemination of the Quran in Europe tracks the evolution of a self-conscious modernity. Renaissance philology, Reformation polemic, and the development of new media all influenced how Europeans received the holy book of Islam in the West. Tracing the story of its publication from the beginning helps to explain the acrimony of these introductions. In the process, it reveals how social conflicts enveloping Europe shaped perceptions of an exotic, heretical Other in the colonial mind. This early history formed an important trajectory for contemporary understandings of Islam in Europe and North America.

Translating the Untranslatable

For theological reasons, rendering the Quran from Arabic into other tongues originated in Christianity rather than Islam. Because the Quran reproduces Allah’s word in Arabic, for Muslims, translation necessarily entails diminution. Neither literal nor liberal rendering in the vernacular can approximate the splendor of Allah’s very words. Amid Babel’s confusion, the Arabic Quran alone commands authority. Privileging the language of revelation guarantees nothing is lost in translation. This commitment ensures the fundamental consistency and orality of the Quran. Like the Latin mass, Arabic resounds from the muezzin around the world, irrespective of the vagaries of local dialect and literacy rates. This linguistic tradition also restricts authoritative exegesis to an educated elite who have mastered Arabic. Only those who can make sense of the text can reach binding verdicts on its interpretation and proper application.

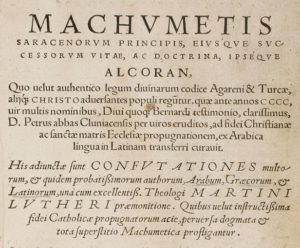

Unbothered by these important restrictions, the Christians who took up the project of translating the Quran faced formidable challenges. It was only with the institutional resources of the monastic center of Cluny that the first translation of the Islamic holy book was completed.

The origins of this undertaking lay in the reconquista and in the missionary initiatives of the monastic reformer Peter the Venerable. Late in the 11th century, an alliance of French and Spanish forces expelled Muslim garrisons from Toledo. The city, home to many Jews, Muslims, and Christians, thus beckoned Peter, now Abbot of Cluny, who saw opportunities for learning and proselytizing. He sojourned for a lengthy sabbatical there. Peter readily discerned that converting Muslims would require familiarity with the Quran. Fired by evangelical zeal, he commissioned a native Arabic speaker and an Englishman, Robert of Ketton, to render the Arabic text into Latin.

Apologetic concerns animated this first translation of the Quran. Its Latin title, Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete (“The Law of the False Prophet Muhammad”), reveals its dim view of the Prophet and his message. Writing to his longtime correspondent (and sometime “frenemy”) Bernard of Clairvaux, Peter described his purpose in similar fashion: “[I’m doing this] to follow the Fathers’ custom of never passing over any heresy in silence, even the most inconsequential (so to speak), but rather resisting heresy with all their faith’s might, and exposing it as abominable and damnable in their writings and arguments.” Peter put the Latin Quran to use in this enterprise, citing from it extensively in his polemics against Islam.

Apologetic concerns animated this first translation of the Quran. Its Latin title, Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete (“The Law of the False Prophet Muhammad”), reveals its dim view of the Prophet and his message. Writing to his longtime correspondent (and sometime “frenemy”) Bernard of Clairvaux, Peter described his purpose in similar fashion: “[I’m doing this] to follow the Fathers’ custom of never passing over any heresy in silence, even the most inconsequential (so to speak), but rather resisting heresy with all their faith’s might, and exposing it as abominable and damnable in their writings and arguments.” Peter put the Latin Quran to use in this enterprise, citing from it extensively in his polemics against Islam.

His efforts cemented an enduring legacy for Christian perceptions of Islam. Negatively, the depiction of Muhammad as a false prophet now became a stock representation. Peter classified Islam as a heresy rather than a distinct religion; the Quran and its disciples as deviants to be corrected rather than outsiders to be enlightened. Still, his apologetic undertaking allowed curious non-Muslim Europeans to explore the Quran for themselves for the first time. This return to the sources, framed by the contest of orthodoxy and heresy, later instigated debates over printing the Quran.

Printing the Unprintable

The Latin Quran Peter commissioned circulated in numerous manuscripts and proliferated across centers of learning throughout Europe. Yet officials erected a cordon sanitaire around the translated Quran, lest it “contaminate” uncritical readers with its heresy. In 1309, Pope Clemens VI outlawed the Quran. No manuscript could appear without an official imprimatur and warning to the reader inventorying its errors. More often than not, the sole purpose of reproducing the Islamic holy book was to denounce it. By controlling access to the forbidden scripture church officials could regulate this “dangerous” volume.

This curation of information ended with rising literacy and a social media revolution. The movable-type printing press became a vector for transmitting radical new ideas in ways officials found impossible to regulate. Printing enabled mass distribution, and appealed directly to the literate public. It undermined traditional authority, unleashing all the liberation and corrosion associated with the advent of modernity. Nowhere was this more evident than in the burgeoning of the Protestant Reformation, which galvanized conflict over the correct interpretation of Christianity across Europe, fragmenting Christendom.

The Reformation challenged Catholic dogma by returning to the sources, capitalizing on advances pioneered by Renaissance philologists to reinterpret them, and using printing technology to amplify their voices. The success of this endeavor prompted questions about what other subjects, formerly closed to enquiry, the reading public might examine anew. With the Ottomans at the gates of Vienna by 1529, the question of printing the Quran arose, even as violence among Christians engulfed Europe.

Publishing the Islamic holy book in this sectarian environment posed serious risks. When Basel publisher Johannes Oporinus attempted to print a new version of Robert of Ketton’s Latin Quran edited by Theodor Bibliander, town councilors suspended his printing license and imprisoned him. The presses stopped. Authorities confiscated copies of the rogue publication.

Efforts to censor the Basel Quran might have met with success had report of its suppression not reached the most influential theologian of the age: Martin Luther. Although Luther shared many of the prejudices of his time, he recognized the need to improve understanding of Islam and its revelation. Perhaps, too, he discerned in the struggle to publish the Quran a parallel to his own mission to make the Bible available to the reading public. In any case, the reformer marshaled his considerable authority to lift the ban on Bibliander’s Quran, assailing Basel with strongly-worded petitions for toleration. His lobbying produced results. By the end of the year, Oporinus was released, and the new Quran appeared with prefaces by Luther and his associate, Philip Melanchthon.

Luther’s writings on Islam, including his preface to the Quran, reveal surprising nuance alongside traditional chauvinism.

To be sure, Luther regarded Ottoman encroachments as a threat to the spiritual, temporal, and domestic order. The “Mohammedan” could only be “a destroyer, an enemy, and blasphemer of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The Turk, he complained in 1529, “ruins all temporal government, and home life or marriage, and his warfare, which is nothing but murder and bloodshed, is a tool of the Devil himself.” Ecumenism was in short supply in the apocalyptic landscape of Luther’s Europe, but his hostility toward the Ottomans and their religion was unmistakable.

Yet, in Luther’s imagination, God could exploit even “the Devil’s tool” to serve his purposes. In a 1541 tract, Appeal for Prayer against the Turk, he identified the Ottoman “scourge” as a “schoolmaster” to a Christian Europe in need of humbling. The discerning reader can’t miss the allusion to Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, where the apostle characterizes Mosaic Law as a “schoolmaster” to train a sinful humanity for Christ’s righteousness. In his famous Galatians commentary, Luther likewise describes the Law as a “schoolmaster”: stern in administering a flogging, yes, but “indispensable” to salvation. Turkish incursions, properly understood, become a call to repentance.

Luther interpreted everything through the dialectic of Law and Grace, so his location of Islam and the Quran on these coordinates makes intuitive sense. He categorized Muslims as partisans of Law along with Jews and Papists (the wrong side of justification, for those keeping score). The Quran resembles papal decretals in form and substance. Just as the “folly and madness” of the Jews was best countered by open debate, so also with Muhammad’s prophecy. Neither Luther’s vituperative commentary on Rome or the Jews should earn admiration today. But in other respects, this Protestant stalwart displayed far more generosity than his contemporaries, considering the Turks morally superior to the Papists. He maintained Rome’s attempt to restrict circulation of the Quran stemmed from fear of disclosing its own brand of moral rigorism. For Luther, Catholic enmity with Islam represents a species of what Freud would later term “the narcissism of small differences.”

This invective betrays the affinities Luther shared with his Catholic opponents. In a sense, Luther’s approach reflected that of Peter the Venerable: the Quran deserves study if only to refute heresy with the truth. “In this age of ours, how many varied enemies have we already seen?” Luther mused in his preface to the Quran. “Let us now prepare ourselves for Muhammed. But what can we say about matters outside our knowledge?” Struck by this realization, he eschewed stereotypes in favor of making real sources available to a wider reading public. Yet it would be a mistake to see this posture as democratizing knowledge of Islam. If Luther put his imprimatur on the Bibliander Quran, he was endorsing a Latin version to an audience educated enough to read it. He wasn’t countenancing vernacular translation, as he had with the Bible — German readers had enough legalism and heresy to occupy them without being tempted by Islam.

For their part, Catholics continued to suppress publication of the Quran and to curtail its reading. Bibliander’s print version of the Latin appeared in the 1559 Index of Prohibited Books, and in regional lists of censored publications. However, Catholic apologists weren’t above exploiting Islam for controversial ends. Counter-Reformation polemicists characterized Calvinists as venerating Scripture and the inscrutable, omnipotent divinity they encountered in its pages as “little better than Mohammedanism.” Heresy made for good terms of abuse.

A Tale of Two Qurans

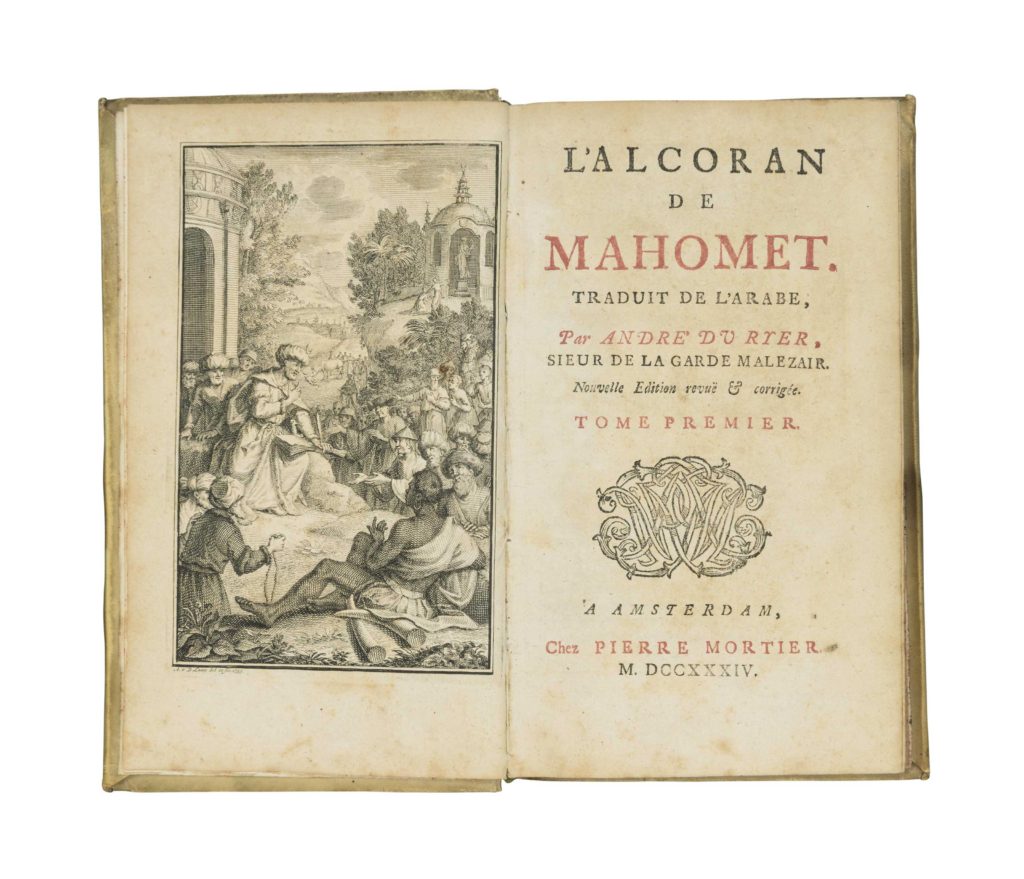

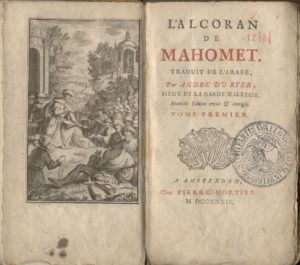

It’s an irony of history, then, that a Catholic Frenchman produced the first vernacular translation of the Quran from the Arabic. Born to a petit noble family in Burgundy, André Du Ryer became interested in Islam not as a theologian, but as a diplomat. An influential patron from a neighboring district, François Savary de Brèves, recognized Du Ryer’s promise early in life and took him on as a client. Brèves himself had served Henri IV as an ambassador to Istanbul and later Rome, and groomed Du Ryer for a career in foreign service. As part of this training, Brèves dispatched his young charge to Egypt to learn Turkish, Arabic, and Persian.

Du Ryer graduated from this apprenticeship to serve out a checkered career in foreign service in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire before retiring to his family’s estate in Marcigny as a man of letters.

What Du Ryer brought back to France was linguistic fluency in Arabic and Turkish, a trove of rare manuscripts (including some prominent tafsīr, or commentaries on the Quran), and an enduring fascination with “the Orient.” More than earlier translators, he cultivated a keen appreciation for Arabic poetics, a sensibility he was to parlay into a best-selling rendering of the Islamic holy book.

The success of Du Ryer’s venture turned on crafting a lively rendering to capture the popular imagination, but also on navigating publishing restrictions of his day. His familiarity with conversational idiom as well as courtly prose imbued his translation with unusual range. Readers found his Quran compulsively readable. Even his detractors conceded this much: he wrote with verve. With some satisfaction, then, Du Ryer could claim, “I’ve made Muhammad speak good French” (j’ay fait parler Mahomet en François).

Convincing skeptical censors of his pious intentions was another matter. Even those who admired his patron, Brèves, harbored suspicions about the elder statesman’s religious sympathies. His protégé would invite the same scrutiny. To allay criticism, Du Ryer dutifully included a preface professing aversion to Islam and an enduring commitment to Roman Catholicism. In his “Address to the Reader,” he designates the Quran “a crude invention of a false prophet” (que ce faux Prophete à inventée assez grossierement). The spread of this infection throughout the world despite facial absurdities should “astonish” (estonné) its audience, he claims, and expose its law as “contemptible” (mesprisable). Far from propagating “the heresy of Muhammad,” Du Ryer claims, his undertaking would bring its self-evident deficiencies to light — a service to the legions of Catholic missionaries abroad in the Islamicate world.

It was a calculated pitch in an era of burgeoning French colonialism. The translation passed muster among both censors and readers. Interestingly, the most prominent missionary of the time, Vincent de Paul, mounted strenuous opposition to Du Ryer’s Quran, but was finally overruled. Curiosity about Islam created pent-up demand, and the retired diplomat’s political connections ensured the publication of his manuscript in 1647 over the objections of the dévots. It became a runaway hit, superseded in French only by Savary’s version in 1783. Imagine a translation of the Tao Te Ching or the Bhagavad Gita reigning atop the New York Times bestseller list, then continuing without a serious rival for almost a century and a half, and you’ll have some appreciation for Du Ryer’s success.

This feat did not pass unnoticed. Only two years after the French Quran came off the presses, it appeared in English translation. This was the edition of Alexander Ross, with the incendiary “Needful Caveat” we encountered earlier.

The translator was a reactionary of the finest vintage. A devoted Episcopalian, Ross had attracted the patronage of Bishop William Laud while serving as a schoolmaster in Southampton. King Charles I would later consecrate Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury, making Ross a client of the most powerful ecclesiastic in England. He became a royal chaplain in 1622, and used this position to establish himself as an arch-conservative polemicist. Ross produced a flurry of tracts denouncing Cartesian rationalism and Spinozism. He was a denier of heliocentric theory. He defended Aristotle against the novelties of Hobbes and Harvey in the realms of politics and physiology.

His fortunes had risen with Laud’s ascent, but when the monarch and his archbishop instigated conflict with parliamentarians and Puritans, Ross’s position as a royal cleric became imperiled. Adversaries had him evicted from his residence at the Isle of Wight. The beneficiary of Laudian patronage was now looking for work.

Ross turned his attention to a preoccupation of his erstwhile patron: religions generally, and Islam in particular. If his later publications are any indication, his distaste for the rise of freethinking may have inspired his interest in world religions. In 1653, he disgorged Pansebeia, Or, View of All Religions in the World, a survey of global religions intended to demonstrate the universality of religious experience and the consequential unnaturalness of atheism. Islam illustrates this claim nicely. “See how vigilant, devout, zealous, even to superstition they are,” lamented Ross, “whereas on the contrary we are very cold, careless, remisse, supine, and luke-warme in the things that so neere concerne our eternall happinesse.” The popularity of Du Ryer’s French Quran may have offered him both the intellectual ammunition and financial incentives he needed to make a name for himself in his changed circumstances.

As in France and Switzerland a century earlier, publishing a translation of the Qur’an proved contentious. Soon after printing commenced, authorities seized copies of the new publication and summoned the publisher and author to court. Although Ross received a favorable ruling, critics soon attacked his enterprise in print. An anonymous controversialist, sometimes identified as the royalist minister Richard Holdsworth, savaged the English Quran and the policy of toleration that licensed its printing. An Answer without a Question, Or, The Late Schismatical Petition for a Diabolicall Toleration of Severall Religions Expounded traffics in a paranoia conservatives stoked throughout the English Civil War. Fears that loosening restrictions on publishing would dissolve Britain in anarchy found receptive audiences. Even Ross’s dependence on a French exemplar aroused suspicion. The pamphlet alleged,

As in France and Switzerland a century earlier, publishing a translation of the Qur’an proved contentious. Soon after printing commenced, authorities seized copies of the new publication and summoned the publisher and author to court. Although Ross received a favorable ruling, critics soon attacked his enterprise in print. An anonymous controversialist, sometimes identified as the royalist minister Richard Holdsworth, savaged the English Quran and the policy of toleration that licensed its printing. An Answer without a Question, Or, The Late Schismatical Petition for a Diabolicall Toleration of Severall Religions Expounded traffics in a paranoia conservatives stoked throughout the English Civil War. Fears that loosening restrictions on publishing would dissolve Britain in anarchy found receptive audiences. Even Ross’s dependence on a French exemplar aroused suspicion. The pamphlet alleged,

“… all the absurd, wicked Blasphemies, and impossible Fictions which were wont to make that wicked volumn justly odious to the world, are left out in the English translation; for my part, I know not how to Construe it, but as done in too much favour to the Maumetan mis-religion; the pretence of the Error must be this, The English Translation follows the version of a Frenchman, too much it seemed Interested in the Turkish Court, for being employed from the French King as his Agent at Constantinople, was likewise re-employed by the Turk into France, and taking upon him to Translate this Worthy Work as he calls it out of the Arabick, thought (for what ends he knew best) to take the best and leave the worst.”

In the opinion of this pseudonymous pamphleteer, Ross had not been too intolerant, but too lenient toward Islam. The Englishman was now fleecing his countrymen with a meretricious Quran purged of its more objectionable content. Ross’s dependence on Du Ryer (whom the author of the broadside assumes had been conscripted into service by the Ottoman court) meant he was infecting unsuspecting Britons with heresy. Ross’s claim about the self-evident absurdity of the Quran was a dangerous myth. Only the censors could resolve this crisis by cutting off its circulation. With opposition this conspiratorial, the hyperbole of Ross’s “Needful Caveat” makes more sense. Fear and fascination make good marketing tools, and it’s no surprise Ross’s Quran was a success in England — and in North America.

***

Translating and disseminating the Quran in Europe were enterprises fraught with peril. Censors suppressed publication. Authorities made arrests and suspended printing licenses. Critics poured scorn on translations, disparaging their scholarship and protesting them as channels of heresy. Even the close associations with predominately Muslim countries necessary to arrive at reliable translation aroused suspicions of a kind of religious Stockholm Syndrome. For all these reasons, translators included apologias at the beginning of their volumes.

These Quranic prefaces expose the tensions that helped to form the modern world. Sectarian divisions ran deep in early modern Europe, and attitudes toward the Quran became an important proxy for fighting these battles. Interestingly, all parties regarded Islam not as a distinctive religion, but as a self-evident heresy. This taxonomy made it a useful instrument for polemical exchanges. Protestants like Luther charged that Islam was like popery, and favored printing. (Even George Sale’s widely-respected translation of 1784 claims, “The Protestants alone are able to attack the Koran with success.”) Catholics restricted distribution of the Quran, and hurled “Islam” as an epithet to attack Protestants.

While it’s tempting to interpret the appearance of vernacular translations from the Arabic as a triumph of Enlightenment, the prefaces furnish evidence that the myth of progress rests on a foundation of oversimplifications (to say the least). Du Ryer’s translation represents a considerable philological and stylistic achievement, yet marshals familiar tropes in its address to its readers. Ross assailed Islam and freethinking while also laying the foundations for a study of comparative religion, projecting an exotic Other to throw the contours of “true doctrine” into stark relief. In a real sense, the “Modern West” used Islam to develop the boundaries of its own identity. Attitudes toward translating and printing the Quran helped shape the world we live in now, where nearly two of three Americans view this tradition negatively.

Today, printing restrictions have largely vanished; anyone can choose from a variety of Quran translations at their local bookstore or public library. Yet prejudices anchored in history tend to persist. As the genealogy of these lurid introductions indicates, the rise of a self-conscious modernity in early modern Europe arose at the same time as Islamophobia. This twinned development is no coincidence. Modern discourses about “the West and the Rest” contrast a “civilized” Occident with an “exotic Orient.” As Tomoko Masuzawa has shown, so does the comparative study of world religions. Neither tradition tends to acknowledge how this invention of the Other was crucial to its own self-fashioning. It’s fitting, then, that I discovered the history of Quranic prefaces in a donation bin at school. What gets discarded is often what we most need in order to learn — both about ourselves and others.

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of two scholars of Islam, Jessica Couch and Yunus R. A. Wesley. Their insights, bibliographic suggestions, and encouragement helped make this project possible. In a number of places, they’ll recognize valuable information they supplied. Where I’ve erred, I hope no one will hold them responsible.

Ryan T. Woods earned his doctorate in religion at Emory University in 2013. He teaches at Georgia State University and serves as an Associate Editor for Marginalia Review of Books. His interests range from early Alexandrian Christianity to Cleveland sports.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.