India Cracks Down on Hindu-Muslim Couples Under “Love Jihad” Laws

A conspiracy theory sweeping India that is leading to the persecution of interfaith couples

(Image source: Article 14)

They had known each other for nearly a decade, living in the same neighborhood on the outskirts of Delhi. Akbar Khan, a Muslim man who ran a small public service center, and Sonika Chauhan, a Hindu woman who worked at a nearby beauty parlor, fell in love and quietly married in August 2022, without telling their families.

For almost two years, little changed. Chauhan continued to live with her parents, who opposed the relationship, while Khan stayed in a nearby apartment. The two did not move in together, hoping Chauhan’s family would eventually accept their marriage. But on May 24 this year, after her father allegedly beat her and forced her to sign divorce papers, the couple fled so they could live together as a married couple away from their families. A day later, police arrested Khan after Chauhan’s father filed a complaint accusing him of kidnapping and forcing her into marriage.

Before his arrest, Chauhan had recorded a video from a moving car, sitting beside Khan, saying she had married him of her own will. “He is my husband,” she said. “We have been together for nine years. No one has forced me.” Despite her statement, police charged Khan with abduction and wrongful confinement.

It was only later that reports revealed how local leaders of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and affiliated Hindu groups had intervened, helping Chauhan’s family to track the couple and urging the police to act. BJP leader Meena Bhandari said, “I do accept that I came forward to help the Chauhan family in this case. I will keep doing whatever I can to have miscreants like him [Khan] punished.”

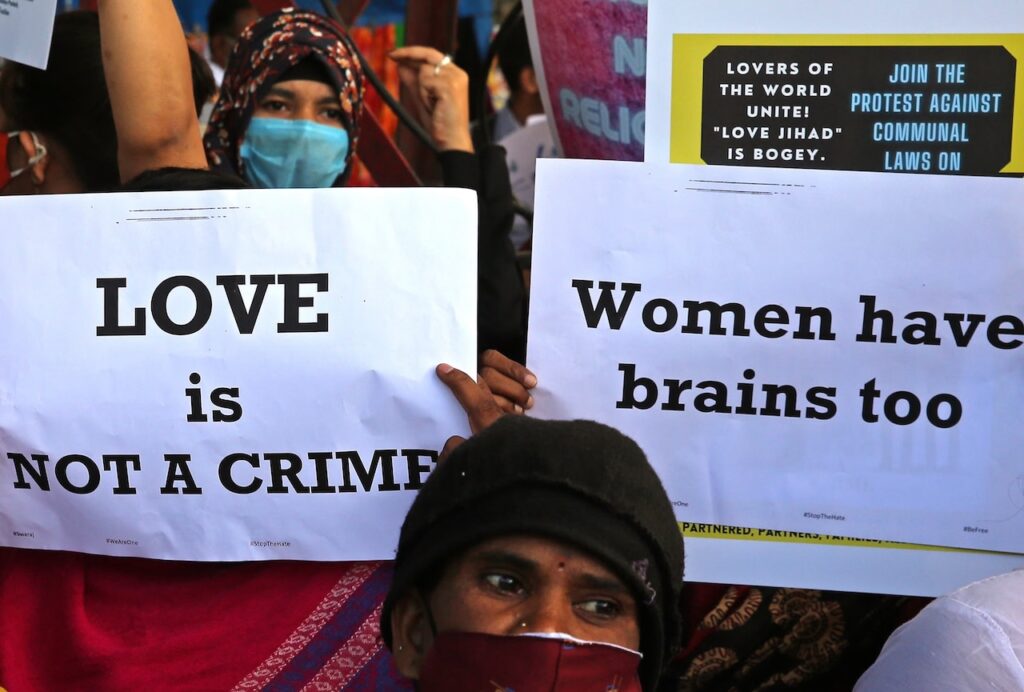

In India, such interventions by Hindu nationalist groups have become increasingly common, with relationships between Hindu women and Muslim men often framed as cases of deceit or coercion: what Hindu nationalists call “love jihad,” a conspiracy theory claiming that Muslim men lure Hindu women into marriage to convert them into Islam.

The narrative draws on long-standing fears about Hindu women’s vulnerability and Muslim men’s supposed hypersexuality and cunning. Right-wing Hindu leaders, including Uttar Pradesh’s hardline Hindu monk and chief minister Yogi Adityanath, have repeatedly claimed that Muslim men are deliberately seducing Hindu women to convert them and “alter India’s demography.” Similar rhetoric has been echoed by members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) the BJP’s ideological fountainhead, who describe it as a “population jihad” — a strategy to outnumber Hindus by marrying and impregnating Hindu women.

(Image source: The Independent)

India’s 2011 Census, however, shows Hindus comprise around 79.8% of the population, while Muslims make up 14.2%. Between 2001 and 2011, the Muslim population grew by 24.6%, compared with 16.8% among Hindus. Yet fertility rates for both communities have sharply declined over time. The latest National Family Health Survey shows Muslim women have an average of 2.6 children, compared with 2.1 for Hindus—a gap that has steadily narrowed. Despite the lack of evidence for any organized campaign or demographic threat, politicians and Hindu nationalist groups continue to frame interfaith relationships as a conspiracy to “trap naïve Hindu girls” and “turn them into child-bearing machines.” Data from the Centre for the Study of Organized Hate shows that nearly half of all hate speeches in 2024—581 instances, or 49.9%—referenced conspiracy theories. “Love jihad” remained the most persistent of these narratives.

Vigilante Hindu nationalist outfits have exploited the “love jihad” conspiracy theory and have harassed, assaulted, and in some cases killed Muslim men in relationships with Hindu women. Couples have been dragged to police stations, forced apart by families, or paraded before right-wing media as examples of “rescuing” Hindu women. Several cases have ended in mob violence, often justified as acts of “protection” of Hindu women’s honor.

Rights groups say such attacks are part of a broader climate of impunity—in which religious nationalism is used to justify the policing of intimacy between consenting adults—and political mobilization against minority communities.

Activists also say such attacks are part of a broader plan to consolidate India as a Hindu-majoritarian state—one where Muslims are barely tolerated. This agenda manifests in laws that criminalize interfaith marriages and conversions, and campaigns that portray Muslims as demographic or cultural threats.

In this atmosphere, love in India has been sharply polarized by Hindutva—the majoritarian ideology that seeks to define the nation in explicitly Hindu terms. The private act of spousal or partner choice has been turned into a public test of loyalty, where a Hindu woman’s relationship with a Muslim man is no longer seen as personal, but as a measure of her fidelity to her religion and her nation.

When Families, Laws, and Mobs Unite to Police Love

In India, marriage remains a deeply conservative institution, still governed by markers of caste, class, religion, and kinship that dictate who can marry whom. Nearly 90% of all marriages are arranged by families, while only around 2% are interfaith. “People prefer their children to marry within their own religion and caste. Among these, one of the biggest taboos is a union between a Hindu and a Muslim—it’s seen as scandalous, especially if the man is Muslim,” says Asif Iqbal, founder of Dhanak, a Delhi-based support group that assists interfaith couples.

Yet, across villages and small towns, young people are increasingly defying these boundaries. With the spread of mobile phones, cheap data, and social media, they are meeting beyond traditional social groups and falling in love in growing numbers. But the backlash is often swift and brutal. In many places, families and vigilante groups have united to prevent such relationships from existing. “They will stoop to any level to stop them—parents even tarnish their daughters’ reputations to deter her lover’s family. The so-called ‘love jihad’ narrative has become yet another weapon to discourage such unions,” Iqbal adds.

India’s own legal framework also makes such marriages difficult: interfaith couples must marry under the Special Marriage Act, which requires a public notice period, often exposing them to social backlash and threats before the wedding can even take place.

Historically, marriage in India was governed by personal laws tied to religion—meaning interfaith couples could not marry unless one converted. In 1872, the British introduced India’s first interfaith marriage law, but it required both partners to renounce their religion altogether. This was replaced in 1954 by the Special Marriage Act, allowing people of any faith to marry without conversion.

However, there was a catch. The Special Marriage Act mandates a 30-day public notice period before the marriage, during which time the couple’s personal details—names, addresses, ages, occupations, and photographs—are displayed in the registrar’s office for public scrutiny. The clause, as parliamentary debates from the time reveal, was designed to prevent “runaway couples” from marrying without the knowledge or approval of their families. In effect, it ensured that elopement remained difficult.

Legal experts have long criticized this provision for violating the couple’s fundamental right to privacy. According to Asif, the Act’s procedures make the process needlessly cumbersome, exposing couples to delays and public scrutiny.

“As part of the process, couples have to appear in court twice—first to give notice and again after 30 days for the marriage to be solemnized,” says Asif. “In that time, their details—names, addresses, photographs—are made public either through clerks, lawyers, or government websites. That’s when local groups start tracking them.”

He explains that organizations such as the Bajrang Dal, RSS, and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), among other Hindu nationalists, closely monitor these notices. “They often reach out to the girl’s family first, informing them that their daughter is planning to marry outside her religion,” Asif says. “If the family doesn’t act, these groups themselves step in—sometimes even going with them to the police station to file a complaint against the man.”

Reports suggest that these organizations have established systematic networks to track and disrupt interfaith marriages. In Bhopal, such groups tracked down an interfaith couple after their marriage notice was flagged, with right-wing lawyers and activists alleging “love jihad.” Similarly, in Kerala, notices of interfaith couples were leaked on social media, exposing them to harassment and threats. In Uttarakhand, a couple’s details went viral after being uploaded to a government portal, forcing them into hiding.

To circumvent the bureaucratic hurdles of the Special Marriage Act, some interfaith couples choose to elope, with one partner converting to the other’s religion. However, in nine BJP-ruled states, recently enacted anti-conversion laws treat such marriages as potentially criminal. These laws, popularly referred to as “love jihad laws,” broadly declare marriages invalid if one spouse is deemed to have converted under coercion, allurement, undue influence, or fraudulent means—terms that are often vaguely defined.

Under these laws, the burden of proof falls on the accused, effectively assuming that any marriage involving conversion is non-consensual unless proven otherwise. Any family member of the “alleged victim” can register a complaint, which can quickly lead to the arrest of the spouse, usually the husband. Across India, parents commonly weaponize the law—filing kidnapping or rape charges—when a daughter elopes or marries against their wishes, stripping her of legal protections and personal freedoms while criminalizing her fully lawful decision to live with a partner and exercise her right to choose whom to marry.

This pattern is evident in Uttar Pradesh, where the state’s “love jihad” law, implemented in March 2021, quickly led to a surge in cases. In just the first month of the law’s implementation, authorities filed 16 cases targeting 86 individuals, 79 of them Muslims. By November, the crackdown had intensified, with 108 cases naming 257 people, encompassing not only the men involved in interfaith relationships but also their relatives and acquaintances.

“In most cases under this anti-conversion law, the complaints come from family members, not the women allegedly affected. Despite repeated requests, the state has disclosed very little data,” said Akram Akhtar Choudhary, human rights lawyer and co-founder of Archive Against Humanity, to Al Jazeera.

These provisions, critics argue, create vast opportunities for abuse: authorities or vigilante groups can target and harass minority communities and interfaith couples, often using family objections as justification. The result is a legal and social environment in which personal choice in marriage is criminalized, and interfaith couples are routinely exposed to intimidation and punitive action.

The Homecoming

Shirish Solanki, a Hindu man from Vadodara in Gujarat, had been in love with Anisha, a Muslim woman, since he first saw her in their first year of college in 2009. Over time, their friendship deepened, and they eventually began dating. When they decided to get married, both approached their families for consent—but faced strong opposition from both sides. Shirish was even pressured to get engaged to someone else. “At that point, I went into a depression,” he recalls. “I decided that if we wanted to be together, we had no choice but to elope.”

Initially, they considered registering their marriage under the Special Marriage Act in Vadodara. But the proximity to their families and the likelihood of their plans being discovered made this impossible. Under mounting pressure and seeing no other way forward, the couple sought help from Iqbal’s organization for interfaith couples, Dhanak, and eloped to the capital.

“When we first came to Delhi to register our marriage, we expected interference, but what we encountered was unexpected,” Shirish says. “During the notice period, we received calls almost every other day—not threats, but offers of assistance from the RSS [the parent organization of the BJP] and other Hindu leaders. They promised to arrange the wedding, provide protection from Anisha’s family, help convince our parents, and even offered financial support—sometimes offering as much as one to two lakh rupees—to facilitate the marriage.”

Unlike marriages between Muslim men and Hindu women, which Hindu nationalists typically frame as coercive, Hindu organizations tend to portray unions between Hindu men and Muslim women as instances of romance and love. “This aligns with the broader Hindutva narrative,” says Asif.

The Hindu Mahasabha, a right-wing Hindu nationalist group, exemplifies this dual strategy. In 2015, rather than their usual protesting of Valentine’s Day, it marked it by organizing interfaith weddings. While these unions were celebrated as love, the non-Hindu partner had to convert to Hinduism beforehand, reinforcing the notion that such marriages are acceptable only if they uphold Hindu religious and social hierarchies.

Shirish, however, chose to avoid such support. Two months after arriving in Delhi, he and Anisha were married. Bureaucratically, their process was smoother than that of other interfaith couples they knew—particularly those in which the groom was Muslim. After their marriage, the couple sought protection from the courts, which was granted when they returned to Vadodara. “For the first year, we were provided a house by the court and assigned four police personnel for protection—two stayed with my wife at home, and two accompanied me at the university where I work,” Shirish recalled.

Such protection proved essential, as young people in India who make personal choices in defiance of community norms sometimes face fatal violence, including attacks by their own families. Interfaith couples who marry after conversion in states with anti-conversion laws face additional hurdles. Many find it extremely difficult to meet the onerous legal requirements imposed by these laws, often leaving them vulnerable to harassment or violence from family members, with little recourse to protection.

“These couples also require proper rehabilitation and support,” said Asif Iqbal. “They often experience physical and mental trauma, separation anxiety, and guilt. To address this, the Supreme Court’s directive to establish safe houses and special cells for couples in each district should be fully implemented.” He emphasized that such measures are crucial not only to safeguard couples’ lives but also to protect their constitutionally guaranteed rights to personal choice and autonomy.

At present, only two states in India have operational safe houses for interfaith couples, leaving many without formal protection.

Meanwhile, campaigns, organized rallies, and even mainstream media—including films in Bollywood—have contributed to the propagation of the “love jihad” narrative, repeatedly framing interfaith relationships as a threat. These efforts perpetuate the idea that adults, particularly women, are incapable of making informed choices about their own lives and relationships, and that they can be manipulated or seduced by men from minority communities.

In doing so, the narrative not only casts a shadow over interfaith love but also sanctifies intrusion into private lives, turning the most intimate human bond—love itself—into a battleground of politics and ideology. Each year, new conspiracies are coined to sustain this paranoia: population jihad, land jihad, beauty parlor jihad—the list grows almost daily, blurring the line between the absurd and the dangerous. Together, they mark a deeper unease with the very presence of Muslims and Muslim culture in India, recasting ordinary expressions of life, work, and affection as threats to a Hindu nation in the making.

Anuj Behal is an independent journalist and urban researcher based in India. His work explores the intersections of religion, injustice, diaspora migration, and climate change. His bylines include The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Nikkei Asia, Thomson Reuters, and more.