In the News: Mourning, Reckoning, and Looking Ahead

A roundup of recent religion writing.

We promise we’ll do our best to end this roundup with some good news, but we’re going to start with one of the most urgently important religion-related stories we read this summer, Kathryn Joyce‘s report on The Threat of International Adoption for Migrant Children Separated from Their Families for The Intercept

“What’s the legal status of the kids down the road?” asked Linh Song. “The longer they stay, will there be foster parents who will contest for custody and adopt? It would be one thing if the kids are going as unaccompanied minors or teens. But if you have an infant with you, I bet there are parents who won’t want to give that child up.” She said, “What’s the likelihood of an indigenous Guatemalan mom fighting a family in western Michigan with access to law firms and large, conservative Christian megachurches? It’s really daunting.”

A young immigrant holds his belongings in a Homeland Security bag while waiting to enter the bus station after being processed and released by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, in McAllen, Texas, on June 22, 2018. Photo: David J. Phillip/AP

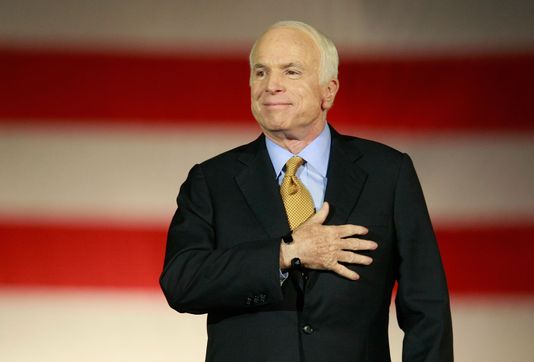

And keeping with the topical and dire, do make sure to read Patrick Blanchfield‘s deep cut on The John McCain Phenomenon by for The Baffler.

This narrative of abandoning self-seeking in favor of something greater taps deep wells, mythic and even theological, while also trading in popular narrative tropes of personal redemption. McCain the young man, conceited but daring and with a roguish charm, is made to suffer, but learns thereby the values of self-sacrifice and leadership. His youthful disrespect for the proper authorities is transmuted into defiance of abuse at the hands of improper authorities, and then into a nobility of proper authority in his own right—while preserving the added frisson of his old independent-minded iconoclasm. The reckless Hotshot becomes the Maverick, who happens to always vote the same way as the Company Man; Han Solo, but for Empire.

And Katrhyn Lofton‘s No God but Country: The Religion of John McCain Has Something Important to Tell Us, for Religion Dispatches, makes a great religion-focused companion piece.

As I proceed here with a study of McCain’s religious words and religious acts, it is worth noting that there is no test, no catechism, and no shibboleth (as much as the voting public may, for whatever reason, desire one) that will prove religious identity or personal commitment to a specific God. People say and do a lot of things they don’t actually mean. Trying to know what people actually do believe, or what they actually do mean, requires psychic skill far beyond the purview of most refereed journals, most tenured academics, and certainly beyond the polygraph limits of the American media. Remember (yes, you, Senator McCain; you, Senator Obama; and you, voting Americans): words of faith are precisely that: words. To know a man’s religion as an observer (a voter, a journalist, a scholar, an outside believer) is to know, only and entirely, his language game. This is John McCain’s.

John McCain (Getty Images)

Lofton also Revisited: Sex abuse and the study of religionfor The Immanent Frame

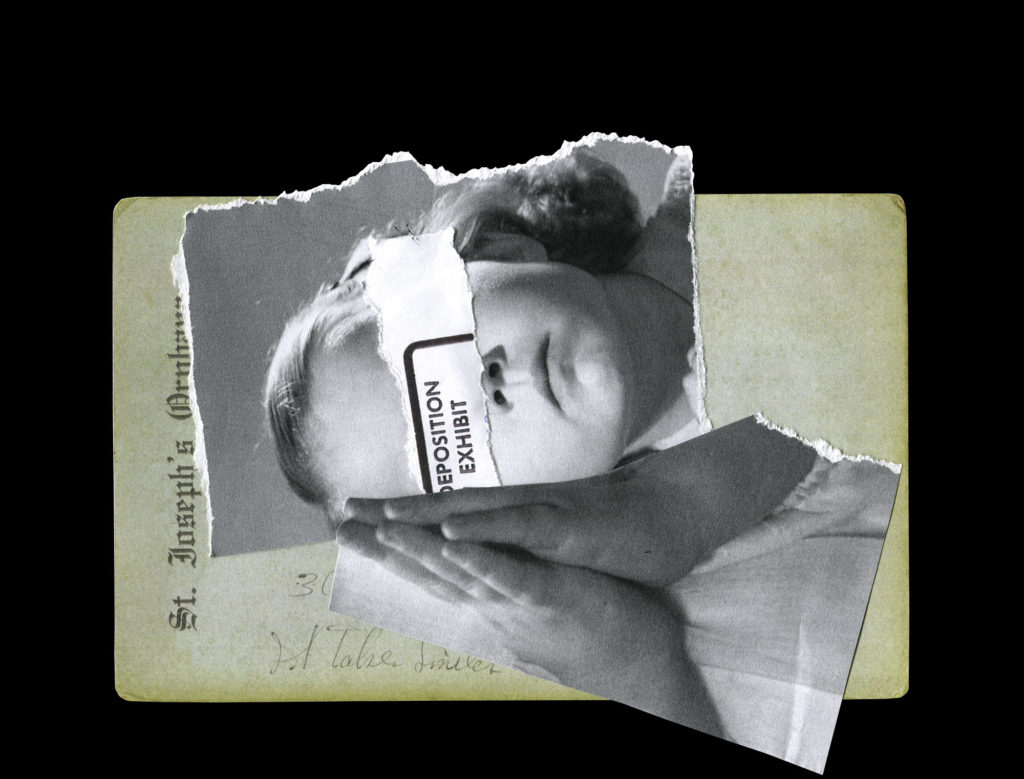

Our goal was to explore the specifically Catholic cultural, theological, moral, even ontological, contexts within which this abuse took place, and then to consider the questions and issues this raises more broadly for the study of religion. To do this, we turned to an online archive developed by BishopAccountability.org, an organization that seeks to gather and preserve the archives emerging as a result of the sex abuse revelations in the Roman Catholic Church.

Which inspired us to revisit this terrific piece by The Revealer‘s publisher, Angela Zito, from 2010, Imagine this! Or Can a Church hierarchy become a Catholic community?

Human beings form communities imaginatively, by being able to make metaphors for action for themselves out of the strangely different, yet seductively engaging life-experiences of beloved Others. Not just any others, but people with whom you live, work and struggle. Up close. Every day. We are always alone together. The Church has no women’s experiences enriching the daily life of administrative work or its workers, no openly gay people to challenge the imagination of its hierarchy. Whether women, gay or straight, get there by ordination, by marrying priests, or by coming out does not matter—I leave that to the theologians.

Which you should definitely read before you take on Christine Kenneally‘s long and painful Buzzfeed.News report, We Saw Nuns Kill Children: The Ghosts of St. Joseph’s Catholic Orphanage .

Outside the United States, the orphanage system and the wreckage it produced has undergone substantial official scrutiny over the last two decades. In Canada, the UK, Germany, Ireland, and Australia, multiple formal government inquiries have subpoenaed records, taken witness testimony, and found, time and again, that children consigned to orphanages — in many cases, Catholic orphanages — were victims of severe abuse. A 1998 UK government inquiry, citing “exceptional depravity” at four homes run by the Christian Brothers order in Australia, heard that a boy was the object of a competition between the brothers to see who could rape him 100 times. The inquiries focused primarily on sexual abuse, not physical abuse or murder, but taken together, the reports showed almost limitless harm that was the result not just of individual cruelty but of systemic abuse.

In the United States, however, no such reckoning has taken place. Even today the stories of the orphanages are rarely told and barely heard, let alone recognized in any formal way by the government, the public, or the courts. The few times that orphanage abuse cases have been litigated in the US, the courts have remained, with a few exceptions, generally indifferent. Private settlements could be as little as a few thousand dollars. Government bodies have rarely pursued the allegations.

So in a journey that lasted four years, I went around the country, and even around the world, in search of the truth about this vast, unnarrated chapter of American experience. Eventually I focused on St. Joseph’s, where the former residents’ lawsuits had briefly forced the dark history into public view.

Then you can read Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez On her Catholic faith and the urgency of a criminal justice reform in America Magazine.

Discussions of reforming our criminal justice system demand us to ask philosophical and moral questions. What should be the ultimate goal of sentencing and incarceration? Is it punishment? Rehabilitation? Forgiveness? For Catholics, these questions tie directly to the heart of our faith.

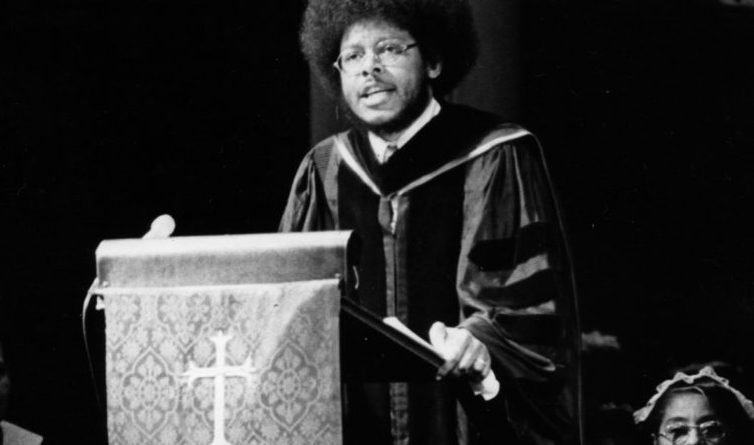

And Anthea Butler writing From the church to the public stage, Aretha Franklin earned her respect for America Magazine.

The pain of women in patriarchal spaces is real. The black church, much like the Catholic Church, was a space in which women filled the pews but men controlled their destinies. Aretha’s gift to us is not only her voice, but her legacy as a proud and successful artist: In the patriarchal spaces of the music world as well as the church world, she demanded respect for her talents and her work. In a time of men, Aretha Franklin stood out as a woman whose voice was a conduit for the Spirit of God and the longing for love that we all seek. Perhaps she was not ethereal, but her earthiness gave us something of the divine in her powerful voice. May she rest well, as a good and faithful servant of God.

Aretha Franklin performing at a benefit for her father, the Rev. C. L. Franklin, in Detroit in 1980. Credit: Leni Sinclair/Getty Images

You know who really loves Gospel? Headline writers. First up, The Gospel According to Kendrick Lamar by Lisa Robinson for Vanity Fair.

Since he says he was confident as a kid, and he’s confident now, why were there all those self-doubts he’s written about that came in between? “I never thought about it like that,” he says. “That’s a question I’m going to ask myself tonight. Maybe it’s that fear . . . a lot of artists have a fear of success, they can’t handle it; some people need drugs to escape. For me, I need the microphone—that’s how I release it. And just figuring out a new life. Maybe thinking that I’m doing something wrong, or that I’m a little bit different or gifted. It’s the same thing as not wanting to accept compliments. Just wanting to work harder.” As for what’s next: “I don’t know,” he says. “And that’s the most fun part, the most beautiful part.” I ask him if, as he sings in “ELEMENT,” he would “die for this shit,” and he says, without a second’s hesitation, “I would.”

Next, Gospels of Giving for the New Gilded Age by Elizabeth Kolbert for The New Yorker (okay, to be fair, the Gospel reference in this one is topical, and not just headline bait.)

We live, it is often said, in a new Gilded Age—an era of extravagant wealth and almost as extravagant displays of generosity. In the past fifteen years, some thirty thousand private foundations have been created, and the number of donor-advised funds has roughly doubled. The Giving Pledge—signed by Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Michael Bloomberg, Larry Ellison, and more than a hundred and seventy other gazillionaires who have promised to dedicate most of their wealth to philanthropy—is the “Gospel [of Wealth]” stripped down and updated.

And last, The Gospel of Elon Musk, According to his Flock by Bijan Stephen for The Verge .

Gomez isn’t alone. She’s one member of a vast, global community of people who revere the 46-year-old entrepreneur with a passion better suited to a megachurch pastor than a tech mogul. With followers like her, Elon Musk — the South African-born multibillionaire known for high-profile, risky investments such as Tesla (electric cars), SpaceX (private space travel), the Boring Company (underground travel), and Neuralink (neurotechnology) — has reaped the benefits of a culture in which fandom dominates nearly everything. While his detractors see him as another out-of-touch, inexpert rich guy who either can’t or won’t acknowledge the damage he and his companies are doing, to his fans, Musk is a visionary out to save humanity from itself. They gravitate toward his charisma and his intoxicating brew of extreme wealth, a grand vision for society — articulated through his companies, which he has an odd habit of launching with tweets — and an internet-friendly playfulness that sets him apart from the stodgier members of his economic class. Among his more than 22 million followers, all of this inspires a level of righteous devotion rarely glimpsed outside of the replies to a Taylor Swift tweet.

Michael Peterniti wrote about a different kind of leader in Jimmy Carter for Higher Office for GQ .

About 40 Sundays a year, Mr. Jimmy materializes from thin air, flickering before us at Maranatha to lead Bible study, to say, No, the world’s not going to end. Not just yet. Though he’s elfin with age, you’d still instantly recognize him as our 39th president: with those same hooded ice-blue eyes, the same rectangular head, the same famous 1,000-watt smile. But when he teaches like this, he transforms from whatever your vision of Jimmy Carter is into someone different, some kind of 93-year-old Yoda-like knower, who in his tenth decade on earth still possesses that rarest of airy commodities: hope.

And Black Perspectives published a forum about the great James Cone which includes terrific work by Judith Weisenfeld, For His People: James H. Cone and Black Theology, and Xavier Pickett, Honoring the Sacred Fire of James Cone (below) among others.

While his rage against injustice emboldened him to speak into the present with an eye toward the past, it also enabled him to create a future where academic Black theology would exist. It is tempting to believe that his rage was incidental to his thinking, but I think rage was integral to his thinking. For Cone, as I understand him, rage is a form of thinking. Cone’s rage forced white theology into the furnace of Blackness, thereby forging a new theology with Black fire. This new theology made of fire became the conduit through which he unleashed the power of his mind.

(Black Perspectives also published Alexis Pauline Gumbs great essay on the problem with the passive past tense which we highly recommend.)

For more from Weisenfeld you can listen to Hillary Kaell interview her about her book, New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration, for the New Books Network.

A wave of religious leaders in black communities in the early twentieth-century insisted that so-called Negroes were, in reality, Ethiopian Hebrews, Asiatic Muslims, or a raceless children of God. In New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration (NYU Press, 2017), historian of religion Judith Weisenfeld argues that the appeal of these groups lay in how they rejected conventional American racial classifications and offered alternative visions of black history, racial identity, and a collective future.

And of course, there are stories about seekers: Amar’e Stoudemire Is on a Religious Quest writes Sam Kestenbaum for The New York Times

Mr. Stoudemire had just announced, only hours earlier, hopes of returningto the N.B.A. after leaving two years ago, but he’d reserved the afternoon for showing his spiritual side.

At 35, he is part sports mogul, part holy man. With some 15 years as a basketball star, Mr. Stoudemire has stepped out as an entrepreneur, dipping into the art and fashion worlds, opening a winery and publishing a series of books. He is also taking what he frequently calls a “spiritual journey” into the Bible, Israel and Judaism. It’s a turn that has fascinated and confounded some observers.

And Rachel Yoder wrote about her own experiences in The Mindfuck: Returning to My Mennonite Homeland at Lit Hub.

I suppose I wanted to find some original Rachel Yoder there in Shipshewana, perhaps the essential Rachel Yoder. I suppose I wanted to see what it felt like to be Rachel Yoder in a place where Rachel Yoder made sense, to wind up on a native expanse of land. I suppose I was trying to be Mennonite, as I once had been, or even Amish, as my father had once been. I suppose I was trying to understand something about the past or, if not understand, come to terms with it. Plus, my uncle ran some sort of museum there and wanted me to visit the place.

If the news lately has you wondering just where the world is headed we recommend reading Amy Brady‘s interview with Roy Scranton in Some New Future Will Emerge for Guernica. (Scranton has written for The Revealer about climate change before in: Climate Change and the Dharma of Failure.)

If the news lately has you wondering just where the world is headed we recommend reading Amy Brady‘s interview with Roy Scranton in Some New Future Will Emerge for Guernica. (Scranton has written for The Revealer about climate change before in: Climate Change and the Dharma of Failure.)

The American understanding of war as trauma came out of an older tradition of understanding war as revelation. That idea emerged in Europe with Romanticism. You can see it in novels like War in Peace and Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, and in poems by [the English poet and soldier] Wilfred Owen. In one of Owen’s poems, the narrator has a traumatic revelation when he sees his friend die in a gas attack. The moment opens his mind to a kind of “truth of existence” that civilians can never understand. Then there are novels like Ernst Junger’s Storm of Steel, which is also about understanding war as this revelation of truth, but for him, war isn’t traumatic. It’s not about death; it’s about the future, and it’s beautiful. But these interpretations are two sides of the same coin. They both draw from this transcendental knowledge that war gives access to revelation.

If all of this leaves you wishing the weekend had been just a bit longer, well, give this a read: Benjamin Y. Fong on the religious origins of Inventing the Weekend for Jacobin

Reid concludes that “the eradication of Saint Monday did real harm to the actual and potential quality of working-class life. Half a day was given in exchange for a whole one; in submitting to the norms of industrial capitalism the notion of a proper balance between work and leisure was lost.” But remembrance of Saint Monday is more than just a lamentation for a bygone form of life, one where work made more sense, where we had more control over its rhythms, and where the “unpurposive passing of time” had not yet been funneled into structured play. It is also a reminder of what is to be gained once again.

And if you want something superb to watch this weekend, watch Hannah Gadsby‘s “Nanette” and then read Briallen Hopper‘s response, Hannah Gadsby Makes it Plain, for Killing the Buddha.

In divinity school they taught us to preach the sermon we needed to hear, because others would need to hear it too. That is what Hannah Gadsby has done.

Finally, well, you already know how we feel about witches; we’re also very into Naomi Fry, who wrote about The Many Faces of Women Who Identify as Witches in The New Yorker

The witch is often understood as a mishmash of sometimes contradictory clichés: sexually forthright but psychologically mysterious; threatening and haggish but irresistibly seductive; a kooky believer in cultish mumbo-jumbo and a canny she-devil; a sophisticated holder of arcane spiritual knowledge and a corporeal being who is no thought and all instinct. Even more recently, the witch has entered the Zeitgeist as a figure akin to the so-called nasty woman, who—in the face of a Presidential Administration that is quick to cast any criticism as a “witch hunt”—has reclaimed the term for the feminist resistance. (This latter-day witchiness has often been corralled to commercial ends: an Urban Outfitters shirt bearing the words “Boss Ass Witch,” say, or the women-only co-working space the Wing referring to itself as a “coven.”) The muddled stereotypes that surround witches nowadays are, in the end, not so very different from those used to define that perennial problem: woman.

“Kir (Brooklyn, NY)” photo by Frances F. Denny

Okay, that’s it for this month, we’ll see you again in October!