In the News: Cruelty, Comedy, and Communists

A roundup of recent religion writing.

Welcome back for another installment of things we have read that we hope you’ll read, too. This month’s selection is by no means comprehensive — there is so much to read and process and respond to — but it is a collection of the pieces we most wanted to share with you.

And if you’re looking for something to listen to, we can’t recommend these two Longform Podcasts with New York Magazine staff writers highly enough. First up, the wise, and irreverently reverent art critic, Jerry Saltz. And second, the indispensably sharp and galvanizing feminist journalist Rebecca Traister. Their conversations aren’t about religion, but they are about how to write, study, think, and we think everyone could use a dose (or two) of that right now.

Alex Prager for The New York Times. Painting by Vanessa Prager

Now, for the reading:

This gorgeous essay, How Maya Rudolphs Became the Master of Impressions , by Catie Weaver for The New York Times Magazine, made an otherwise hellish commute heavenly.

Supposing that God is real and possessed of a human corporeal form — mankind being created in his image (reportedly) — we might reasonably conjecture that God’s anthropoid body integrates the totality of physical traits expressed in Earth’s human population: the skin tones blended to a light tan; the hair dark and thick; the height neither too tall nor too short — about 5-foot-7, say; every shade of human iris (the iridescent blue of a morpho butterfly, the pale green of lichen clinging to a tree, lots of brown) combining to create eyes that are … also brown. Considering his propensity for giving life, God would probably be a mother. Considering his appreciation of beauty (e.g., snowflake geometry) and busy schedule (e.g., Genesis), he would probably clothe himself in breezily tasteful garments made from natural fabrics cut for maneuverability, like a long denim jumper dress worn over a shirt of pure white cotton. God would look, in other words, like Maya Rudolph running errands on a Tuesday.

Measuring 28 feet by 12 feet, the “Queen’s Window” represents a hawthorn, a thorny floral shrub, in bloom.CreditVictoria Jones/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

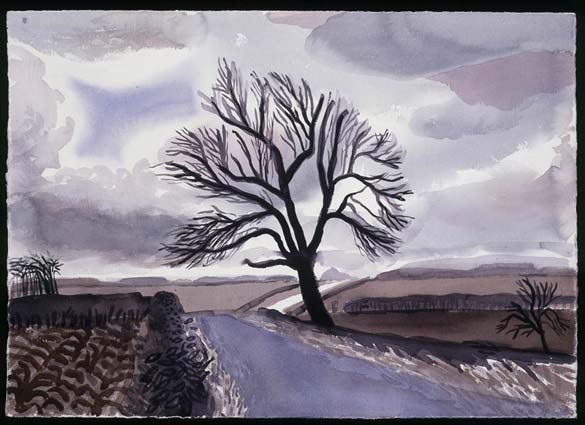

This gem also provided welcome does of charm on an otherwise grim subway. Turns out, David Hockney Wouldn’t Paint the Queen. By Farah Nayeri for The New York Times.

As a church, Westminster Abbey could not be more intimately linked to the monarchy. Thirty-eight sovereigns were crowned there, and 17 are buried on site. Mr. Hockney would not seem an automatic choice for it. The onetime bad boy of British art has spent the better part of the last five decades in Los Angeles, and in 1990, he turned down a knighthood, though he is no adversary of the monarchy, he said. “I was living in California. I didn’t really want to be Sir Somebody,” he explained.

In 2012, Mr. Hockney accepted an invitation from the queen to join the Order of Merit… But when he was later asked to paint her, he turned that down, too. In the interview, he recalled Mr. Freud’s depiction of the monarch. “He got 10 hours from her, which is not very much for him, but a lot for her to sit,” said Mr. Hockney. “I knew the portrait. It was O.K. But I’m not sure how to paint her, you see, because she’s not an ordinary human being.

“She has majesty,” he added. “How do you paint majesty today?”

And we’d miss our stop to keep reading Molly Crabapple‘s piece, My great grandfather the Bundist

When the Bund is acknowledged at all today, it is often characterized as naive idealism whose concept of Hereness lost its argument to the Holocaust. But as I watch footage on social media of Israeli snipers’ bullets killing Palestinian protesters, I think that Bundism, with its Jewishness that was at once compassionate and hard as iron, was the movement that history proved right.

Or maybe we should get out of the city altogether? A Trip to Tolstoy Farm by Jordan Michael Smith for Longreads

But there was another Tolstoy who’s been lost to history. For all his fame as a novelist, in Russia and elsewhere Tolstoy the fiction writer was secondary in fame and impact to Tolstoy the author of political, social and religious non-fiction. “His popular celebrity in 1910 owed more to his political and ethical campaigning and his status as a visionary, reformer, moralist, and philosophical guru than to his talents as a writer of fiction,” the classicist Mary Beard has observed. Though it’s remembered today only by a few literary critics, Tolstoy fashioned an entire coherent way of living centered around his unique understanding of Christianity. Its adherents came to be known as Tolstoyans, much to his annoyance. At one time, there were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of practicing Tolstoyans around the world, from India to Canada. They renounced cities, comforts, laws, pleasure, modernity. Now they’re all gone. Almost all.

But no, we’re staying here in New York, but we’re grateful to California-based Popula for bringing us pieces like,What it is like to Celebrate Mass by Edmund Wadstein, O.Cist.

To try to celebrate Mass with one’s whole heart is also to be filled with a desire to combat corruption in the Church. As a Catholic priest, the abuse scandal in the Church is given an extra edge of horror to me by the fact that the abusers were priests, supposed to have consecrated their lives to the Holy Sacrifice. What they did instead was the exact opposite. Instead of “this is my body offered up for you,” they essentially said, “this is your body, which I am going to take.” That fills me with anger.

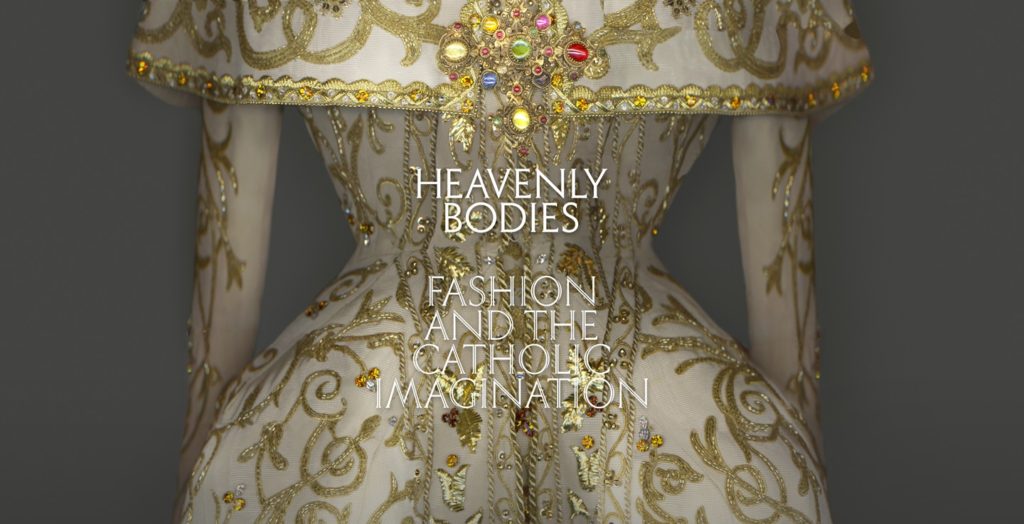

And New York isn’t all bad, at least we get to go see the show everyone is writing about in this new series atThe Immanent Frame: Couture and the death of the real: A response to Heavenly Bodies with contributions by Robert Orsi, Brenna Moore, Emma Anderson, and Stephen Schlosser.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute’s Spring 2018 exhibition, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination, has been described as “a dialogue between fashion and medieval art from The Met collection to examine fashion’s ongoing engagement with the devotional practices and traditions of Catholicism.” Among the artifacts on display are dozens of pieces, including papal robes and jewels, never before seen outside the Sistine Chapel Sacristy. The papal objects are juxtaposed alongside baroque-style dresses from leading fashion houses—among them Dolce and Gabbana, Versace, and Dior—to demonstrate the longstanding influence of liturgical vestments on international designers. While fascination with Catholic dress is not new, the exhibit raises many questions about the Vatican’s involvement in light of histories of American anti-Catholicism and philo-Catholicism. And as this exhibit came in the midst of what Robert Orsi in his introduction to the forum describes as “the worst crisis in the history of modern Catholicism,” issues of sexuality, aesthetics, and power are brought into view.

On another subject entirely, this sounds about right: There are too many gurus in America by Heather Havrilesky for LitHub

The guru is not an expert in happiness or inner peace, although he plays one on the internet. He is not a role model in the realm of fighting injustice or saving the world from disease or throwing his body onto the battlefield. He is a champion of the self. His livelihood relies not only on the defeat of human emotions, but on a denial of the existence of prejudice, of resistance, of the machinery of oppression, of the impenetrable forces that maintain the status quo, of the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, of the disastrously callous habits of the overclass and the bought-out legislators who serve them. The guru will not instruct you on how to navigate a world that distrusts or despises you, nor will he acknowledge that the landscape you inhabit was built to keep you poor, powerless, and suspect.

In other words, the guru is an expert at gaming privilege.

And we definitely cannot not talk about the gutwrenching, infuriating, harrowing, frankly, just totally fucked up, appointment of Justice Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court last week. But, we’re grateful for Talia Lavin‘s advice on How to Fight Back Doom in the Age of Kavanaugh in The Daily Beast

To live in a time such as this—in which children are separated from their parents and incarcerated; in which racism and spite and greed and theocratic zeal seem the only animating forces of our government—it is worth remembering that there have been worse and blacker times, and there were those, even then, who fought on in the bilious dark.

And when there are stories about sex and gender in the news, our list of “must reads” always includes Jia Tolentino (as well as Lili Loofbourow, who is quoted in the next two pieces). Her latest, Brett Kavanaugh, Donald Trump, and the Things Men do for Other Men, is essential:

Part of the reason the Kavanaugh news cycle has been such a flashpoint—part of the reason that so many conservatives have fanatically defended his right to have hypothetically committed the crime he’s been accused of, and that so many women have been spending the last two weeks in a haze of resurfaced trauma—is that it illuminates the centrality of sexual assault in the matrix of male power in America. In high schools, in colleges, at law schools, and in the halls of Washington, men perform for one another and ascend to positions of power. Watching it happen is a deadening reminder, for victims of sexual assault and harassment, that, in many cases, you were about as meaningful as a chess piece, one of a long procession of objects in the lifelong game that men play with other men.

As is Adam Serwer‘s analysis in The Cruelty is the Point, for The Atlantic

Trump’s only true skill is the con; his only fundamental belief is that the United States is the birthright of straight, white, Christian men, and his only real, authentic pleasure is in cruelty. It is that cruelty, and the delight it brings them, that binds his most ardent supporters to him, in shared scorn for those they hate and fear: immigrants, black voters, feminists, and treasonous white men who empathize with any of those who would steal their birthright. The president’s ability to execute that cruelty through word and deed makes them euphoric. It makes them feel good, it makes them feel proud, it makes them feel happy, it makes them feel united. And as long as he makes them feel that way, they will let him get away with anything, no matter what it costs them.

Lastly, these two pieces from The Poetry Foundation, fully and totally blew us away last month, so, we leave you with them.

Dumb Messenger by Anjulia Fatima Raza Kolb

After the Shakuntala, which leaves little space for the reader’s mind, I had no taste for Kalidasa or Sanskrit drama, for God or gods. I didn’t have Sanskrit either, though by this time I had begun the process of learning the grammar of Urdu, a language I understood, I realized, the way you “understand” the shallow tessellation of a chain link fence or a creeping wall of fog before you resolve it in three dimensions. What killed me dead was the Meghdoot, “The Cloud Messenger,” one of the stunning messenger poems in which a concept or creature is conscripted into delivering a message to a distant beloved.

The poem is long. The parts I loved most were the parts with no people and no gods. I thought it was about a lover left at home who seeds a cloud with the message of her longing, and sends it off over the mountains and the rivers, the temples and the forest fires, to find her beloved, to rain down nothing less than the enormity of her missing.

I was so dazzled by the idea of a woman impregnating a cloud, which she calls all kinds of affectionate names—o, elephant; o, fat man; o ponderous lump. I read the poem again and again for the parts where the cloud goes on his own journey, takes every particulate feeling and minced up blood up into the ether, and holds it there in celestial oathspace. Damn!

And It’s Not Like Nikola Tesla Knew All of Those People Were Going to Die by Hanif Abdurraqib

Everyone wants to write about godbut no one wants to imagine their god

as the finger trembling inside a grenadepin’s ring or the red vine of blood coughed into a child’s palm

while they cradle the head of a dying parent.Few things are more dangerous than a man

who is capable of dividing himself into several men,each of them with a unique river of desire

on their tongues. It is also magic to pray for a daughterand find yourself with an endless march of boys

who all have the smile of a motherfucker who wronged youand never apologized. No one wants to imagine their god

as the knuckles cracking on a father watching their sonpicking a good switch from the tree and certainly

no one wants to imagine their god as the tree.Enough with the foolishness of hope and how it bruises

the walls of a home where two people sit, stubbornly in lovewith the idea of staying. If one must pray, I imagine

it is most worthwhile to pray towards endings.The only difference between sunsets and funerals

is whether or not a town mistakes the howlsof a crying woman for madness.

East Yorkshire, watercolor, David Hockney, 2004

***