I Want to Be Haunted by the Ghost

An obituary for Sinéad O’Connor

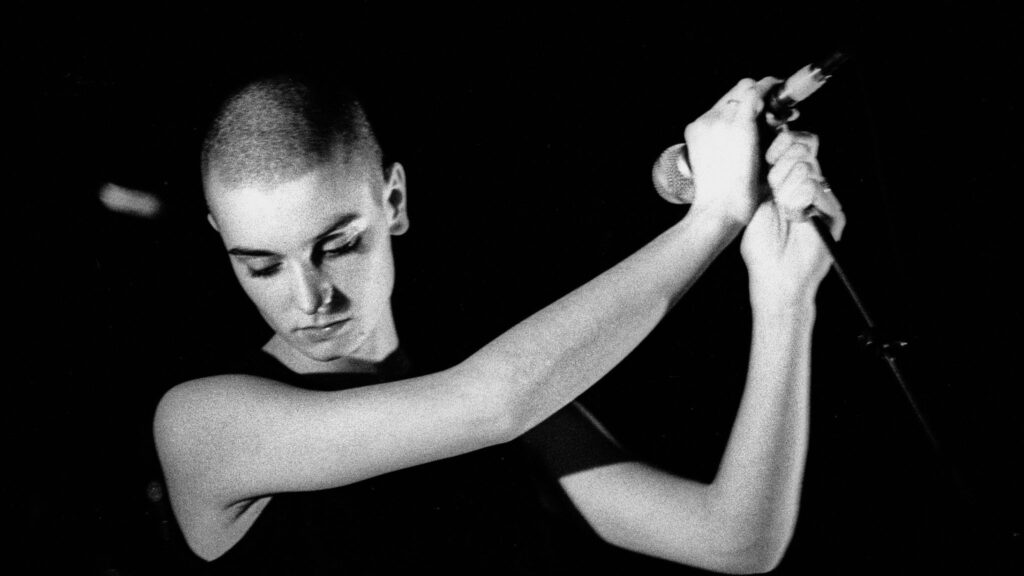

(Image source: Paul Bergen for Getty Images)

“I had the incredible honour of sharing the stage and studio with the head chief many times, and she brought me on tour where I sat at her feet every night and watched in awe as she waked the dead and soared like an eagle, singing our ancestors alive, and fighting the eternal fight of good against evil. … She had the soul of a punk, fearless in what she believed in, and wielded her art like a sword to cut at the psychopaths of the earth…”

—Damien Dempsey

***

In 1990, the fabled music journalist Legs McNeil profiled Shuhada’ Sadaqat—then known as Sinéad O’Connor—for SPIN magazine, just weeks after her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, catapulted her to A-list celebrity status for her rendition of Prince’s ballad “Nothing Compares 2 U.” This was two years before O’Connor’s fame would evolve into infamy after she tore up her abusive mother’s photograph of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live as she sang a rendition of Bob Marley’s “War.” McNeil’s essay was essentially a confession of love that feels slightly embarrassing to read: “Dazzling and captivating eyes, the most beautiful Irish brogue and skin that looked like it would melt butter. I wanted to stare at her but I was trying to be cool, you know, just catching glimpses of her when she wasn’t looking my way.” Long before we had the language of “parasocial relationships” with famous people, McNeil, like almost everyone I knew, was in love with Sinéad O’Connor. Legs McNeil might have been self-confident enough to say the quiet part out loud, but Sinéad O’Connor had the rare quality of making you want to cry, dance, and scream—all simultaneously and in equal measure.

McNeil interviewed O’Connor on the day she learned “Nothing Compares 2 U” had hit #1 on the U.S. singles chart. She was immediately reticent about the dangers of that level of celebrity: “I don’t want to be a rock star, I don’t want to be treated like one, and I don’t want any of the associations that go with it. I just want to be treated like an ordinary person, and I want people to remember that the most important things in my life are not making records and going around the world on tour. The most important thing is my family, and my spiritual beliefs. If I didn’t have those things, I wouldn’t be inspired to do anything.”

Nobody becomes that famous entirely by accident, or without wanting it at some level—you don’t just slip, trip, and inadvertently record a heartbreaking cover of a Prince song. But maybe akin to the 16th century mystic Juan de la Cruz, who coined the term “dark night of the soul,” O’Connor was suspicious of the hazards of celebrity for one’s spiritual integrity—whether that celebrity was earned through MTV or renown as a contemplative monk.

Legs McNeil described Sinéad O’Connor as a kind of Joan of Arc figure, because she was, in his words, “a study in contradiction”—delicate yet feral. It was a comparison that would be made repeatedly over the years, partially due to the aesthetic similarities between the “Nothing Compares 2 U” music video and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). In her memoir, Rememberings, O’Connor claimed to have shaved her head to undermine the sexualization of her appearance by record label suits—which had the unintended effect of turning her exposed cranium into an icon of iconoclasm—the soon-to-be “avatar of a million dreamy rebellions.” It was also more complicated than that, tied to experiences of trauma, and joy, and freedom: later in life, O’Connor would elaborate on additional reasons for the cut, including painful reminders of her abusive mother and as a self-defense mechanism against the unwanted advances of industry creeps.

She violated every rule in the pop playbook: in addition to going bald and tearing up a picture of the pope on live television, she skipped the Grammy Awards in 1991 when she was a nominee, decrying the music industry as ethically perverted, corrupting what she saw as the artist’s vocation as spiritual healer. And that was two years after she’d performed at the Grammys with a temporary tattoo of Public Enemy’s crosshairs logo on her head to protest the racist exclusion of hip-hop from the ceremony—while also wearing her son Jake’s onesie from her belt loops to flip off record executives who’d told her motherhood would derail her career. She refused to let a stadium in New Jersey play the U.S. national anthem—or anyone’s national anthem—as the intro to her concert, which led an acrid Frank Sinatra to suggest she be deported.

Sinéad O’Connor was a genius at “show, don’t tell” tactics for her activism. An icon of the Gen X plain-text statement t-shirt—two of her greatest hits were poignant yet laconic: a black-text-on-white “RECOVERING CATHOLIC” slouchy and a “WEAR A CONDOM” crop top showing her exposed pregnant belly, barely years after Ireland had legalized contraception in 1980. And she had a compulsion towards picking fights with bullies—whether it be politicians, clerics, or other artists.

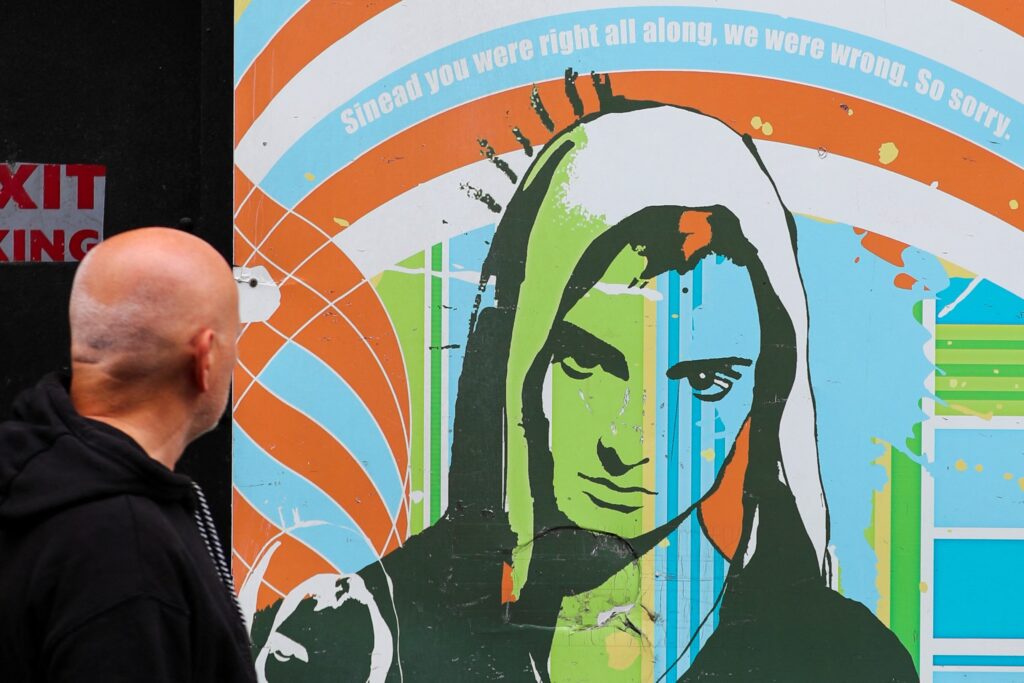

(Image source: Damien Storan for Reuters)

But O’Connor wasn’t impervious to the ire she drew for standing up against injustice—all you have to do is watch the video of her getting booed off stage during Bob Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden two weeks after the SNL incident. Drowning out the boos with her own righteous indignation, she stands so tall with her jaw clenched, rips out her earpiece, and absolutely wails a piercing cut from Marley’s “War”—a callback to the SNL performance. But she crumples and starts convulsing as she leaves the stage, famously into the arms of Kris Kristofferson. In Rememberings, O’Connor recalls the event in explicitly theological terms:

Now I’m asking God what I should do. I keep pacing, which becomes uncomfortable for everyone backstage because the show’s got to go on as planned, so someone dispatches Kris Kristofferson (this he tells me later) to “get her off the stage.” As he’s making his way there, I get my answer from God: I’m going to do what Jesus would do. So I literally scream the biggest rage I can muster, the Bob Marley song “War” to which I tore up the pope’s picture. And then I almost get sick.

I see Kristofferson walking up to me. I’m thinking, I don’t need a man to rescue me, thanks. It’s so embarrassing. “Don’t let the bastards get you down,” he says into my mike [sic]. And we go offstage and I almost barf on him as he gives me a hug.

Afterward, I feel like Bob Dylan is the one who should have come out and told his audience to let me sing. And I’m pissed that he didn’t. So I glare at him in the wings as if he’s my big brother who’s just told my parents I skipped school. He stares back at me, baffled. He’s looking all handsome in his white shirt and pants. It’s the weirdest thirty seconds of my life.

My father, who was in the audience that night, advises me afterward that it might be time for me to reconsider college, because I just destroyed my career. He’s right. But I don’t care. Some things are worth losing your career for. And I don’t want a pop-star career anymore anyway because nobody knows me and I’m so lonely.

The scene is an excruciating video to watch—it feels like we’re audience to public spectacle violence, a crucifixion. But in retrospect, this assault and the longer-term fallout highlighted the contradiction between O’Connor’s values and the ways of the world: she would come to describe it as a redemptive moment; that the apparent obliteration of her career was actually what saved her spirit. It also didn’t shut her up: she continued to speak publicly about injustice, particularly on sexual and gender liberation, as well as the Catholic Church’s years of abuse—and increasingly opened up about her own experiences as a victim of the “Magdalene Laundries,” asylums where tens of thousands of “fallen women,” orphans, and “at-risk” girls were confined, abused, and conscripted into manual labor until 1996.

But perhaps this is why her death was mourned so publicly by Gen X and elder millennial social justice activists in the U.S.: they certainly remember her technical skill—that phenomenal, ethereal voice—in their bones. And they also remember watching her be pilloried on national television for her righteous outrage at racism and child abuse. LJ Amsterdam, an activist scholar and direct-action coordinator, captured the essence of this feeling in a pithy retrospective, following news of O’Connor’s death on July 26: “I remember seeing her on MTV when I was a kid. Her voice. Her vulnerability. Her menace.” adrienne maree brown, author of Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, composed this epitaph, which begins:

what comes first

the madness of seeing thru

to the truth of an institution, a time

or the bravery to point

to show everyone what you see

i suspect it’s the survival

of a brutal childhood

& being told to recover

& being told you are resilient

& being told you are beautiful

when you already know the cost

of looking thru sweet fairy eyes

upon corruption

Sinéad O’Connor was someone we were all scared of, and scared for. She was also someone we wanted. In Kathryn Lofton’s book on Oprah and celebrity as a fundamentally religious phenomenon, she talks about how celebrity renders humans into commodities: we want to consume them—not just what they produce, but their actual being. We could write volumes chronicling the distinctions between Sinéad O’Connor and Oprah Winfrey, but one of the most fundamental elements to O’Connor’s attractiveness was the feeling that she really, authentically, felt uncomfortable with fame at her core, even if she found it sometimes-seductive. Unlike Oprah, or to stick with another one-named planetary celebrity from the great nation of Ireland, Bono—who seem so willing and easeful in their celebrity—we were always told that Sinéad didn’t want it, but did want to use her microphone with integrity.

Many of O’Connor’s obituaries have described her as prophetic about clerical child abuse within Catholicism—but that’s not entirely true. It has become normalized to date The Boston Globe’s 2002 “Spotlight” revelations as the watershed moment in public consciousness about the church’s history of sexual abuse, which is kind of true. However, there had been major news reporting about serial abuse and cover-ups for almost two decades by that point—Gilbert Gauthe in Louisiana being one of the prominent “early” clerical abusers, who was convicted in 1984 for abusing over thirty children. By 1990, just months after Legs McNeil wrote his SPIN profile, HBO premiered a documentary specifically about Gauthe. So it is fundamentally not true that the public didn’t know what was going on when Sinéad O’Connor took action. But that didn’t prevent Madonna and Joe Pesci from mocking and publicly joking about assaulting O’Connor without repercussion.

O’Connor ultimately found a safe haven in Islam. Her mentor, Shaykh Umar Al-Qadri, recalled her as “a wonderful person with a blessed soul,” who found a measure of peace in her new spiritual home. In her own words, she described her 2018 conversion as a “reversion”—because, as a lifelong theologian, “Islam feels like home.”

(Image source: Gus Stewart for Redferns)

Back in the 90s, countless headlines speculated about whether O’Connor was “crazy.” In 2020, Liza Lentini wrote retrospectively about “Saint Sinead” for SPIN and said that she was like “a lamb to the slaughter”—which of course in Christian-speak is a euphemism for calling her messianic. Lentini also compared her to Joan of Arc.

As with the saints, it’s enticing to sanitize her life and talk about how talented and brave she was without also remembering how scary she could be—her “menace,” as Amsterdam put it. Joan of Arc, a warrior who had visions and claimed to have been chosen by God, must also have been terrifying at times. In most iconography, she is cast in stone as dignified and stoic—but she was so much more than that. So as tempting as it is to canonize Sinéad O’Connor in death, and domesticate her memory, she deserves so much more than being retrospectively transfigured into a Francis of Assisi birdbath. Her dangerous memory needs to be protected, because so much of what made her prophetic was bound up in how badly the world treated her in life—and that should continue to implicate us, even as we grieve her departure.

Jack Lee Downey is John Henry Newman in Roman Catholic Studies at the University of Rochester. He is co-creator of Desolate Country, an experimental digital mapping project that tracks the history of clerical abuse in the United States.