How They Met Their Mother

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the divine figure of Heavenly Mother is shrouded in secrecy. Some Mormons are trying to bring Her out into the light.

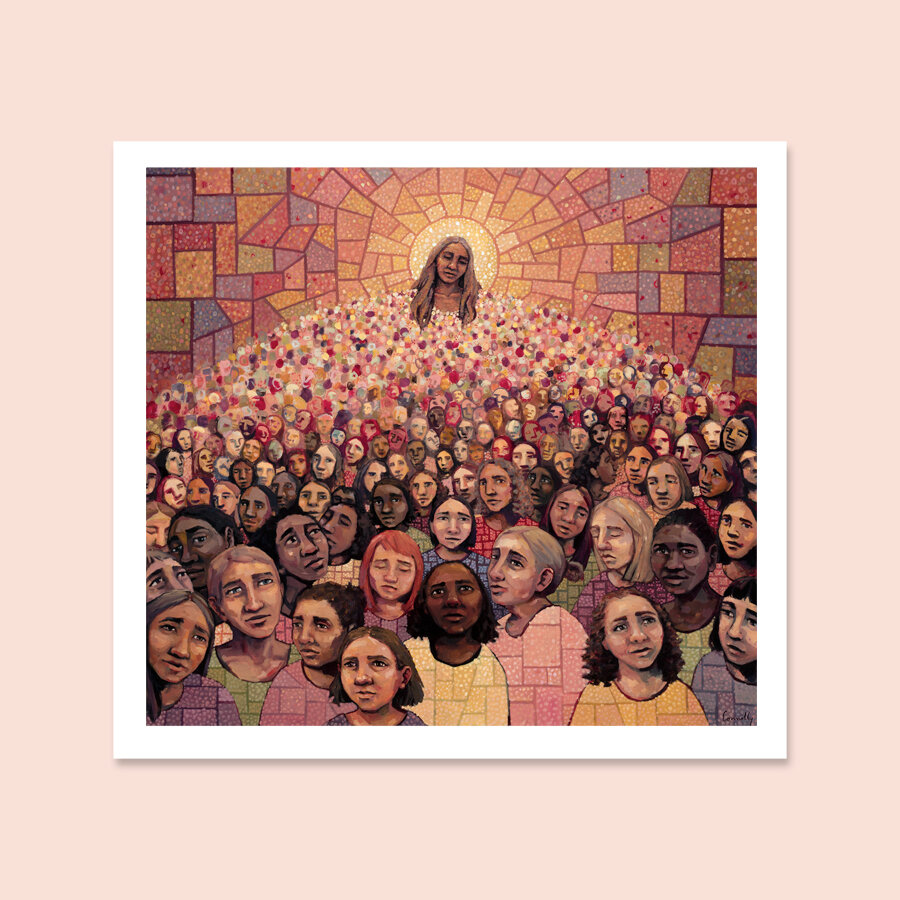

(Image by Catilin Connolly. Visit caitlinconnolly.com.)

On artist Brittany Nguyen’s Etsy site, there is a beautiful painting rich in blues and golds with a scene familiar to many viewers: a kneeling woman with a veil draped over her head holding a beatific baby Jesus sleeping in her lap. But in the top corner of the rendering, a haloed individual floats, reaching out a hand towards the infant. The mysterious God-like being is a representation of Heavenly Mother, an obscure figure in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She’s recognized by Latter-day Saints (LDS) as a partner to the Heavenly Father, a spiritual mother to all, and a special role model for women. She is called Mother God, God their Eternal Mother, and Eternal Mother. Most often, though, She is Heavenly Mother, who some say is so precious and fragile, She must be kept hidden for Her own sake.

But some Mormon feminists, scholars, artists, and poets view this directive as unfounded, even patronizing, and advocate for a greater awareness of Her. They produce podcasts about Her, pen poetry collections dedicated to Her, and craft Instagram platforms around Her. Emboldened by the democratizing force of social media, they dare speak Her name, to the occasional consternation of Church authorities.

LDS theology teaches that the godly and earthly realms mirror one another. In the divine realm, Heavenly Father, as Mormons typically refer to God, has a physical body––although unlike humans’, it is a flawless, immortal one––and is a literal patriarch to humanity and to Jesus, as well as the divine spouse of Heavenly Mother. He rules over His divine family unit in the way that a human man does his earthly family. For Latter-day Saints, earthly existence is a kind of rehearsal for the afterlife, during which they will be reunited with their families, provided they were “sealed” together in a Temple-based ritual during their lives (this is typically a marriage, but children can also be sealed to their parents if they were adopted or born before their parents were sealed). Latter-day Saints also maintain that humans can become God-like by emulating divine values here on earth, or they can more literally become a god in the afterlife. What all this amounts to is that in contemplating Heavenly Father, Latter-day Saint men are envisioning a very real role model for them, an opportunity some Latter-day Saint women crave and feel is unavailable.

Though there are no records of founding prophet Joseph Smith expounding on Heavenly Mother, there is anecdotal evidence that he confirmed Her existence privately. In one of the earliest and best known mentions, the Mormon poet Eliza R. Snow, who was married to Smith until his death in 1844, references Heavenly Mother in her 1845 verse “My Father in Heaven,” which became a popular hymn. “In the heav’ns are parents single?/No, the thought makes reason stare,” Snow wrote. “Truth is reason––truth eternal/Tells me I’ve a mother there.”

Latter-day Saint leaders openly acknowledge that Heavenly Mother exists: the single essay about Her on the Church’s website calls her “a cherished and distinctive belief.” But Church authorities have long dissuaded people from praying to Her or even speaking about Her. In a 1991 speech at General Conference, the biannual event when the highest echelons of the Church address the laity, then-First Counselor Gordon B. Hinckley declared that praying to Heavenly Mother was “inappropriate” and “misguided,” but added that this dictum “in no way belittles or denigrates her.” The idea that Heavenly Mother had to be sheltered for Her own sake had circulated for decades throughout the LDS world, though few people knew where this idea came from. These two things had a chilling effect: many Mormons who came of age around or before that time say they don’t remember any discussions of Heavenly Mother as young people. “The term ‘sacred silence’ is typically used, but I like calling it the unholy freeze,” the writer and Mormon scholar Katie Ludlow Rich said.

The idea that Heavenly Mother needs to be protected with silence is not based in Latter-day Saint scripture. Instead, its most likely origin is a Sunday school teacher named Melvin R. Brooks, who suggested in a mid-20th century LDS reference book that Mormons so infrequently mention Heavenly Mother because She should be protected from having Her name profaned the way God and Jesus’s were so often. It’s unclear why Brooks thought this, or how his conjecture managed to spread so widely, but there are theories as to why it might have been appealing to the Church. Some feminists think that by endorsing a theological version of legal coverture, in which a wife’s legal identity is subsumed by her husband’s, the religion’s patriarchy was able to encourage its female members to remain quiet and docile; others theorized that merely acknowledging Heavenly Mother would make the faith look polytheistic and too distanced from mainstream Christianity. Defenders of Brooks’s sentiment argued that because Heavenly Mother isn’t mentioned at all in scripture, making Her a bigger part of religious worship would be tantamount to inventing new doctrine; they also echoed Hinckley in saying that because scripture explicitly dictates praying to Heavenly Father, one should never deviate from that.

(Image source: Francisco Kjolseth for The Salt Lake Tribune of the Painting “Crafting the Universe” by Lisa Aerin Collett.)

Those who defied the Church’s ruling after Hinckley’s speech faced harsh consequences. In 1995, Gail Turley Houston, an assistant professor of English at Brigham Young University, the Utah-based university closely affiliated with the Church, was fired because she had allegedly promoted praying to both Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother, which the university said “publicly contradict[ed] fundamental Church doctrine and deliberately attack[ed] the Church.” At least three women have been severely reprimanded by or excommunicated from the Church over the course of its history for speaking out on the topic of Heavenly Mother. A number of women recounted to me that they feared being reproached for testifying about Heavenly Mother during services, or that they actually had been.

Even during the last decades’ “sacred silence,” though, people have discovered Her. Rich told me she found herself crying out to Heavenly Mother in the shower after the birth of her second child. She sensed something respond: “Who do you think can stop you from talking to me?” Jessica Smith, a young mother who frequently posts content about Heavenly Mother on social media, first encountered Her while on her mission in Poland. She’d just found out her mother had cancer, and though she wasn’t praying directly to Heavenly Mother, she felt an “undeniable feminine presence” with her. “It was a woman’s voice in my mind, giving me counsel, giving me foresight of my own identity as a woman.” A few years after being thrown out of her house as a teenager by a mother who suffers from a delusional disorder, author Rachel Rueckert read Terry Tempest Williams’s book Refuge, in which Williams writes about connecting with Heavenly Mother after her own mother’s death. “For the first time ever, I uttered this prayer to a mother God,” Rueckert recalled. “To be able to imagine something different and someone who could love me and be so fierce and powerful in that way, it was really transformative to me.”

Over the last decade, there has been a greater acknowledgment of Heavenly Mother within LDS circles. The shift began around 2011, when BYU Studies, a well-regarded academic journal affiliated with the university, published an essay on Heavenly Mother. In it, authors David L. Paulsen and Martin Pulido argued that contrary to popular conception, early Mormon dialogue around Heavenly Mother was quite fluid and generous. The essay opened up the topic for many members of the laity. In the past few years, as Covid kept worshippers away from their traditional places of worship, Heavenly Mother has become something of a cottage industry, with an explosion of books, artwork, and digital content––even downloadable coloring pages––about Her.

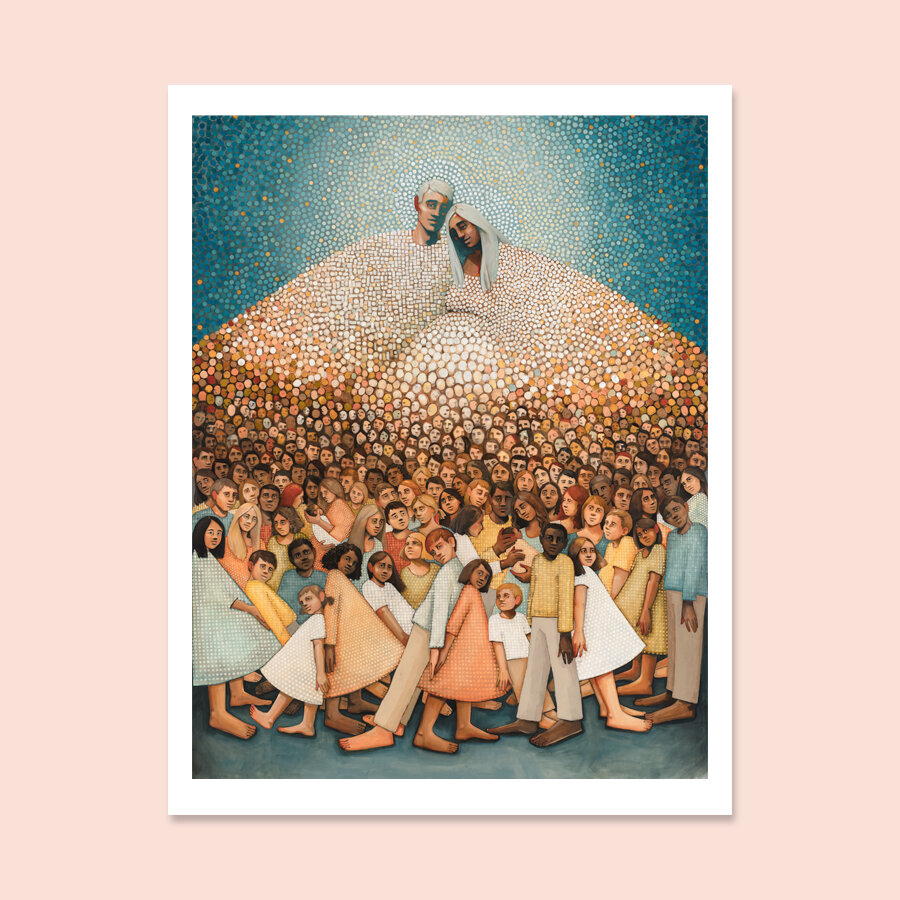

Perhaps as a reaction, the Church proper soon began to incorporate Heavenly Mother more into its environs and conversations. A painting by the well-known Mormon artist Caitlin Connolly depicting a male and a female figure atop a cascade of people, entitled “In Their Image,” has hung in the Church Historical Museum in Salt Lake City since 2019. That same year, the Young Women Theme––a short invocation said by preteen and teenaged girls at Sunday services—was changed by Church officials to include a reference to “Heavenly Parents” instead of Heavenly Father.

(“In Their Image” painting by Caitlin Connolly)

“Young Mormon children, they’re not having the experience me and my peers had,” Rachel Hunt Steenblik, who contributed research to the BYU Studies essay and has written two poetry books about Heavenly Mother, told me. “They’re learning it’s a normal part.”

But many feel the freeze hasn’t thawed yet; though it’s possible to talk about Heavenly Mother on Instagram, it’s less acceptable in official church settings. “You’ll rarely hear someone say ‘our heavenly parents’ plan for us’” at services, Jessica Smith says. “And it makes a difference for women. It makes a difference in how we view a divine being as wise, autonomous, creative, loving, involved.”

When Bethany Brady Spalding and McArthur Krishna began collaborating on books for young adults about Heavenly Mother, they were inspired to do so because they wanted their daughters (they have six between them) to be able to imagine themselves as divine. “If I’m going to raise girls in this faith, they will need and require and demand more,” Spalding told me. “I think our girls are growing in a world where they are limitless… they’re limitless in what they can be and become and see themselves as. And I feel like church is the one place where that is different and it doesn’t have to be.”

Heavenly Mother advocates––who are mostly, but not entirely, women––invoke Mormonism’s own theology as the strongest case for needing a Heavenly Mother: if Mormons are anticipating their afterlives here on earth within the confines of their church and in their families, then women deserve to envision what awaits them. The historical idea of Heavenly Mother gives women little to go on, but what it does give them––a figure so fragile, she’s in need of male protection––is unappealing to many. “This is the only thing we kind of know: she’s silent, she’s quiet. She can’t have a relationship with her children. Like, why would we want this? There’s nothing appealing about this for us,” Hunt Steenblik says. “It’s a matter of identity. What is our place? What will it be for us? Is it something we actually want? Because right now it looks like something we don’t want.”

The stereotype within the LDS world is that women who feel strongly about Heavenly Mother are radical feminists, to be viewed with suspicion. And some people who feel strongly about Heavenly Mother do hold progressive views about how the Church should adapt in a changing world. “I do want women to get the priesthood, partly because I think there’s not a way in the LDS Church currently for their voices to matter as much without it,” Hunt Steenblik said, referring to the rite given to males beginning around age 12, which accords them certain privileges and ritual duties. In research for her 2019 book The Next Mormons, Jana Riess, a senior correspondent for Religion News Service and a Latter-day Saint herself, found that the limited roles for women were among the top ten reasons millennials leave the Church, a marked contrast from boomers, for whom gender parity didn’t rank among the top ten. (Riess isn’t sure changes on this front are imminent: “Our prophet is 98 years old and he grew up in a very different America,” she said, referring to the current head of the Church, Russell M. Nelson. “I don’t think that change is going to come until the leaders who are growing up in this America are leaders.”)

Some also see in Heavenly Mother an opportunity to offer more diverse depictions of godly figures generally. When Krishna and Brady Spalding were commissioning art for their books, they used images that deviated from the “European Jesus” model, a helpful corrective considering the Church’s problematic history with Black members. Krishna’s daughters are biracial, and she wanted to be sure that when they picked up her books, “they could see Heavenly Mother in their own image.”

But for others, the journey to Heavenly mother is not one where institutional change is a priority. The artist Natalie Cosby, who co-hosts a podcast and organizes events on Heavenly Mother, prefers to encourage people to develop their own personal relationships to Heavenly Mother, through prayer or whatever means people find fruitful. “I think that at some point our personal spiritual authority and connection with the Divine has to transcend the institution of the Church,” Cosby wrote in an email. “I don’t believe that the institution of the Church or its leadership can provide all of the answers and nourishment each member needs… and I don’t think its members should depend on it to do so.”

In the spring of 2022, rumors began circulating on social media that one of the speakers at April’s General Conference was going to address the topic of Heavenly Mother. These turned out to be correct: in a speech at the women’s session of General Conference entitled “Your Divine Nature and Eternal Destiny,” Dale G. Renlund, one of the quorum of twelve apostles, who are the Church’s top authority figures, encouraged listeners to see themselves as the daughters of Heavenly Parents, but said all that was known of the matriarch could be found in the church’s essay on the topic, and that people shouldn’t hypothesize beyond that. “Seeking greater understanding is an important part of our spiritual development, but please be cautious,” he said. “Speculation will not lead to greater spiritual knowledge, but it can lead us to deception or divert our focus from what has been revealed.” He repeated the prohibition on praying directly to Her.

“I’ve basically been sad since that talk,” Hunt Steenblik said. “It didn’t give any room for women who want to know more. They didn’t say, okay, you can’t pray to her, but you can … pray to know more about Her.” She said she worried that it is replaying a similar pattern from the nineties, in which rising fear of doctrinal drift was followed by a censorious public statement and then, years later, by a wave of excommunications. Rueckert felt that Renlund’s sentiment was “in tension with Mormonism itself, which was just founded so much on radical questions and radical imagination.” Renlund’s directive revealed one of the deepest tensions within Latter-day Saint theology: the belief in continuing revelation, available to all the faithful, and a rigid hierarchical structure in which the leadership sets guidelines for the entire group. Rich, who wrote a gently critical essay in response for a Mormon feminist blog, contended that the talk tried to have it two ways by affirming Heavenly Mother’s reality and simultaneously enabling leaders to “police women’s thought and talk.”

Others, however, were buoyed by the speech. “I think Elder Renlund’s talk was fabulous,” Krishna said. To her, it provided valuable publicity for the Church’s official essay on Heavenly Mother, which many members around the globe had likely never encountered. Brady Spalding agreed: “I had lots of people come and speak to me afterwards and say, ‘Wow, it was powerful to hear an apostle talk about Heavenly Mother. It was beautiful to hear her name mentioned at General Conference, and it directed me to study her more.’”

Krishna and Spalding even wrote an op-ed for the Salt Lake Tribune to counteract the “doom and gloom,” as Krishna put it, that had dominated the online reaction to Renlund’s speech, and produced a video in which a diverse group of Mormons––young and old, Black and white, men and women––talk about what make Heavenly Mother important to them. “To hear Her mentioned openly in General Conference, it mattered to me,” one participant said.

Some people may imagine a surging grassroots movement around Heavenly Mother would cause a major shift in Church policy, like officially sanctioning praying to Her. But change within the Church doesn’t always come as a result of public pressure or societal trends. One possibility that Jana Riess sees, however, is that the Church might offer incremental changes, like it has done by allowing the children of LGBTQ couples to be baptized, for instance, but stopping short of performing weddings for gay couples. “One thing that I think is a possibility is that the Church might, in a limited fashion, give women some priesthood,” Riess said, particularly if swathes of people leave because of its treatment of Heavenly Mother and other gender-related concerns.

Whatever path the Church decides to take, it’s clear to many that Heavenly Mother can never go back to being solely the purview of fringe feminists anymore. “Technology has changed,” the Mormon scholar, Katie Ludlow Rich, said. “There’s Instagram, there’s Twitter. And people can have this ability to use their voice in a way that can’t be controlled. It can’t be correlated through priesthood.”

Even if there are greater opportunities for the Church to recognize Her, though, it isn’t clear that everyone I spoke to would feel unconflicted about that. Some seemed to worry that if the Church folded Her more into recognized doctrine, She might become limited to what they wanted Her to be. Maybe She’d start to look like the idealized Latter-day Saint woman so familiar from Mormon mom blogs: white, blond, ensconced in her home, surrounded by her many offspring, a supporting character, rather than the heroine. Some were blunt about the fact that relinquishing Her to a cadre of men would be tantamount to a loss. “I don’t want any more of my life regulated by the patriarchy,” Rueckert told me. Outside of institutional control, She could continue to be expansive, creative, open to interpretation. She could be whatever they wanted Her to be.

Kelsey Osgood is a writer based in the Bronx, whose first book, How to Disappear Completely: On Modern Anorexia, was selected for the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Program. Her writing has appeared online and/or in print in The Atlantic, The New York Times, and Wired, among other outlets, and she’s currently at work on a book about religious conversion.