How I Met My Mother (and Billy Graham)

Billy Graham's complicated role in Latin American politics and in the author's family

(Photo courtesy of the Billy Graham Center)

You never learn your family’s history all at once. It comes to you piecemeal, out of chronological order. It starts with you asking your dad why he cooks eggs the way he does and by the end you find out that his first job in the United States was at a bowling alley and he fell in love with your mom at first sight and by the way his nickname in high school was “Mafalda.” From there, the stories repeat. You hear the same Mafalda story at birthdays, cookouts, after church services, when you ask to sleep over a friend’s house, and so on.

Other stories are harder to learn and often go intentionally unspoken. My mother told us that she came to the United States to escape the violence of the Salvadoran civil war — as did much of the Salvadoran diaspora — but I never asked about the war itself. As a child, I didn’t know what a civil war was or what it meant for a country to be at war with itself. In recollections, my mother described the mundane details of an event, like the time she broke a heel on a bus that was hijacked by paramilitary groups. As I got older, I wanted to know how she lived through these times when her life was in peril.

Her answer was that she had found Jesus. She found him as a teenager in evangelical Protestant big tent revivals in El Salvador during the early 1980s. She found him in a Bible with red letters she keeps to this day, well-worn and weathered. He was a comforting Jesus, one who gave her strength amid the social and political turmoil of her times. She clung to this version of Jesus, even as it alienated her from her Catholic family at a time when Catholic suspicion of Protestants grew across Latin America. This family rupture continued after she left El Salvador to the United States in 1983.

These tortured aspects of her spiritual and physical migration seep through when she shares stories about herself. But she also displayed those narratives as artifacts and tangible reminders in our home during the 1990s. I was raised among these items, including Bible verse posters and a collection of novels from the apocalyptic Left Behind series; VHS tapes of Psalty, a Christian children’s program; cassettes of Marcos Witt’s Spanish worship music; books by James Dobson, in English and in Spanish translation. We lived in a bilingual cabinet of evangelical curiosities that differed from my extended family’s Catholic and iconography-laden abodes.

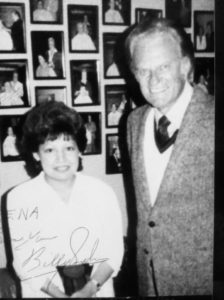

Billy Graham with the author’s mother. (Photo courtesy of the author)

But most prominently among my immediate family’s archive was a framed photograph of my mom with Billy Graham.

This was one of my favorite pictures of my mom: dolled up in full glam with a gravity-defying perm, she appears tiny standing next to “America’s Pastor.” Despite Graham’s celebrity status, here he was, staring into the camera and forever commemorated in our home where he remains for posterity to this day. When I was growing up, I did not think of Graham as someone who was “famous” but as someone who was familiar — his picture in our living room standing next to my mom. Their photo was taken after my mom gave Graham one of several haircuts. Even evangelists need a trim.

My mom was a hairdresser at the Hyatt Regency salon on Capitol Hill in the 1990s. Given the salon’s prominent clientele, hairdressers often made house calls or went to congressional offices for quick appointments. Once my mom rushed to Senator Ted Kennedy’s home in McLean, Virginia for a quick manicure that she conducted as he ate lunch. Her boss noticed her meticulous and caregiving craft and soon recommended her to Billy Graham. Over the years, she would cut his hair when he traveled to D.C. But their professional interactions also had a deeper connection. As an evangelical convert, my mother had a spiritual connection to Graham and, I would later discover, an inadvertently political one as well.

Of course, Billy Graham is a ubiquitous and towering figure of postwar America. He is synonymous with contemporary U.S. Christianity and held a dominant moral presence in political life until his death in 2018. To many, he represents the modern and ecumenical iteration of old-time religion manifested in tent revivals, radio outreach, and direct evangelism. But to millions across the Global South who attended his crusades and supported his association, his impact was a symbol of evangelicalism’s international reach and a disruption to the Catholic majority in Latin America. To my family, he was a symbol of a faith that changed and traveled — from Catholic to evangelical, from El Salvador to the United States. But these global and intimate connections were possible only through American Cold War interventions that were, in large part, the reason for my own mother’s exile from El Salvador.

Reagan, Religion, and Revolution

The late 1970s witnessed unprecedented religious transformations in El Salvador. While Catholic clergy, including notable figures such as Archbishop Oscar Romero, embraced and mobilized the tenets of liberation theology in support of disenfranchised indigenous, poor, and rural communities, an equally powerful charismatic and evangelical Protestant movement spread during this period. As historian David Stoll notes, the rapid expansion of evangelical conversion quadrupled and became one-fifth of El Salvador’s population by 1986. My mother was part of this movement. As she describes it, she came to the Lord first through a family member and then in fellowship with other young evangélicos. This new infrastructure of spiritual and communal belonging was crucial to her navigating tumultuous times in her country.

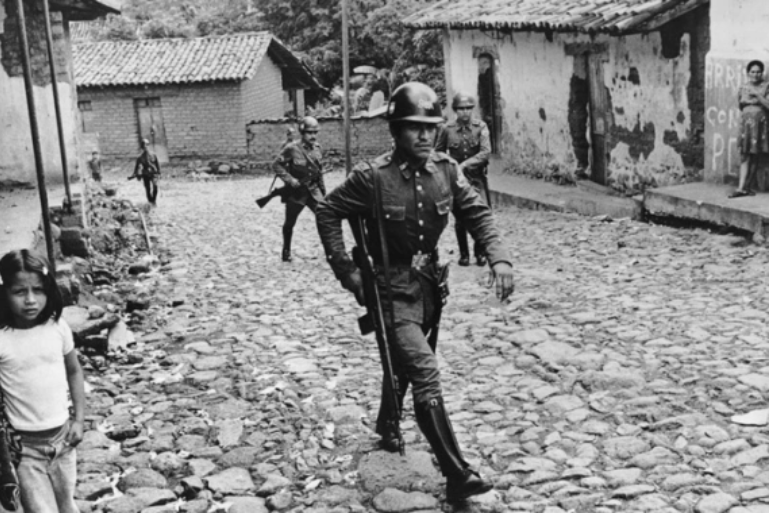

The growth of multifaceted “spirit-filled” forms of evangelical Christianity in El Salvador coincided with the eruption of a brutal civil war that was bolstered by a U.S.-backed right-wing government from 1980 until 1992. Salvadoran leftist guerrilla forces that comprised the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) engaged in armed resistance against the country’s conservative and military oligarchy who indiscriminately used violence against civilians and political challengers. Although the government targeted Catholic clergy for their suspected communist sympathies and their outspoken mobilization against human rights violations, Protestant evangelicals were also subject to violence if they did not express allegiance to the military and state. It was within this context that Graham’s influence, and U.S. evangelical involvement more broadly, thrived in Central America.

Photograph from the El Salvador civil war. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

U.S. intervention in El Salvador had disastrous effects on the region. Under the Reagan administration, the U.S. not only funded, supplied, and trained right-wing rebel groups, known as contras or death squads, the U.S. also diplomatically supported the military and government as it targeted civilians and the leftist FMLN insurgency. Faced with concerns about the rise of communism in the region, Reagan poured billions of dollars to support the Salvadoran state even as the military and its affiliates committed atrocities. Most notably, in 1981 the government’s Atlacatl battalion—trained at Fort Benning, Georgia— murdered over a thousand mostly evangelical and indigenous Pipil peoples in the massacre at El Mozote in Morazán. This massacre remains the largest in modern Latin American history. By the time it ended in 1992, the Salvadoran Civil War claimed over 75,000 lives.

The religious right in the United States, amid their newfound political ascendancy, played an important role in supporting and facilitating a foreign policy that contributed to the violence of the conflict. Moral Majority leaders Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell both advocated for Congress to continue supporting the contras in El Salvador on the basis that the U.S. should cull the spread of communism and advance the cause of religious liberty, by which they meant the spread of Protestantism throughout Latin America. Robertson also donated millions through his ministry to the contras, whom he called ‘God’s Army.” A dual dynamic of increasingly radicalized Catholic clergy — Jesuits in particular — and repression of Protestant converts convinced many American evangelicals that El Salvador was not only a political frontier — it was a religious one.

Billy Graham, and U.S. Power, in El Salvador

But before Robertson and Falwell’s forays into El Salvador, Billy Graham had several decades of experience in Central America. His first time in the isthmus — and indeed all of Latin America —occurred during the Eisenhower administration in the winter of 1958 as part of his Caribbean Tour when he visited Barbados, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Jamaica, México, Panamá, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Although he faced resistance from local governments and the Catholic religious establishment, Graham was welcomed with fanfare at airports, soccer stadiums, homes, missionary outposts, and among small Protestant convert populations. Similar receptions continued for decades.

Known as a proponent of non-partisanship and ecumenical efforts, Graham was often indifferent or at odds with his American counterparts on the religious right. He was outspoken about his purportedly apolitical stances and avoided endorsing policies or electoral candidates in his later years, preferring to lend spiritual support instead to leaders and laity. Indeed, many on the religious right accused Graham of being too ecumenical. Some maintain that this quietist approach guided Graham’s activities in Latin America wherein he avoided becoming politically imbricated in the violent theatre of the Cold War.

But Graham was not as politically uninvolved as he publicly let on. During the 1960s, the Billy Graham Evangelical Association (BGEA) collaborated with the U.S. State Department to share information on the region. Before and after his Andean tour to South America in 1962, he pressured President John F. Kennedy to advocate for Latin American Protestants as a foreign policy priority in the fight against godless communism. His militant anti-communism was not surprising given his religious convictions, but his belief that the expansion of Protestantism was key to winning the Cold War characterized his surreptitious political engagements.

Into the 1970s, socially-conscious Latin American evangelicals challenged the American approach to evangelization — for which Graham was a central figure — for not prioritizing issues around racial differences, social inequalities, and human rights. During the Graham-led global summit of evangelicals at the First International Congress on World Evangelization in 1974, progressive Latin American Protestants focused greater attention on social concerns, informed by liberation theology and the liberal Protestant tradition, by forging a ‘gospel for the poor.’ Progressive evangelicals in the United States supported them and critiqued not only the violent outcomes of U.S. involvement in Latin America — but also the role American evangelicals played in upholding these policies.

This divergence from progressive evangelicals emphasized a key aspect of Graham’s approach to Central America: his conspicuous silence. Despite his early experience in the region and the expansion of evangelicalism, he was not outspoken about the targeting of Catholic clergy in El Salvador or the massacre of evangelicals at El Mozote. He did not advocate for justice over the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was murdered presiding over Mass in San Salvador. This silence becomes all the more glaring as his own son, Franklin Graham, trained chaplains to support the Nicaraguan contras during the same period. For a man known for unequivocal values and outspoken convictions, Billy Graham’s silence over El Salvador is deafening.

President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan with Billy Graham at the National Prayer Breakfast held at the Washington Hilton Hotel in 1981.

Graham’s reach was possible because of his protections as an American citizen and one with powerful friends. Although there were many in the region who referred to him as hermano (brother), his connections, friendships, and movements through Central America were not apolitical. His commitment to U.S. political leaders despite their disastrous policies that contributed to violence in the region and mass exile abroad was not nonpartisan. To claim neutrality as thousands of co-religionists died across the border as a result of U.S. intervention was a position aligned with the political effort to rid Latin America of communism rather than to protect Christians in the region.

The Pain and the Personal of the Archive

These entanglements between Billy Graham, global evangelicalism, the Reagan Administration, U.S. power, and the Cold War — like my own family history — also came to me piecemeal. While I learned about the horrors of the Salvadoran Civil War from my mother as I got older, I didn’t know about the role the U.S. played in fueling the conflict until adulthood. In fact, I first learned about American involvement in the war under seemingly innocuous circumstances and in one of the most ostensibly transparent of U.S. bureaucratic institutions — The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

During the fall of 2011, I decided to write my undergraduate capstone on the post-war settlement in El Salvador. My father and I drove to College Park, Maryland, where I got my picture taken and credentials registered as I headed into the natural light-filled research room on the second floor of our nation’s archive. After passing security checks and procuring approved pencils, I looked into the acid-free archival boxes I requested and reviewed intelligence correspondences, state department reports, and a cocktail of other official papers. Some documents were redacted beyond recognition, while others detailed U.S. interests and priorities in El Salvador during the 1980s. At the end of several days of this sterile and securitized process, I realized that the country to which my family migrated was also the same global power that subsidized the violence that forced them to leave Central America in the first place.

I also recognized that my family’s American evangelical co-religionists were complicit in fueling the wars that raged across Central America. Despite Graham’s reluctance or Falwell’s ignorance, they failed to condemn — or even acknowledge — the human rights violations that took place in Central America. Falwell and Graham never broke a heel on a bus that was hijacked on their way to work, never learned their family was held hostage, nor did they have to leave their country. There was no salvation in Reagan’s interventions and no political allyship among his white evangelical supporters for the more than one million Salvadoran asylees, refugees, and migrants from whom I am descended.

Framed picture of author’s mother with Billy Graham. (Photo courtesy of the author)

I reflect on these entangled pasts when I see the framed photo of Graham and my mother mounted in my family’s living room — an artifact of paper, spirit, and flesh. I imagine the numerous times my mom faithfully manicured his hands, shaved his beard, or cut his hair. I think about the cruelty of historic circumstances that put them in the same room, at the same time, in Washington D.C. A man preaching deliverance, getting a haircut before walking through the halls of U.S. political power and a Salvadoran evangelical hairdresser who fled the violence he was too neutral to condemn.

Today, my mother is the only person who cuts my hair. It is a ritual she performs out of love and care. She repairs the broken ends of my locks and she works through them seamlessly out of familiarity. By removing my dead ends, she initiates a regenerative process in my body and it’s no wonder: she learned how to cut hair in El Salvador around the same time she became an evangelical and before she left her country. These two elements traveled with her from the homeland to diaspora. Maybe a haircut can be more than just grooming. Perhaps it is a healing process, a way to start anew.

Amy Fallas is a writer and historian from Washington D.C. She is the daughter of Central American immigrants and writes about religion.