Hope & Despair: Philosophical considerations for uncertain times

Maybe the only way things will turn out okay is if we accept that they might not.

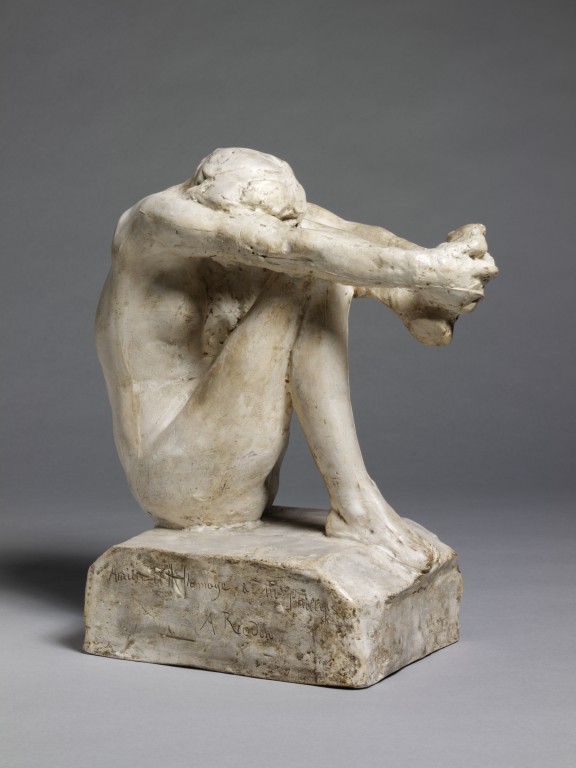

Section of August Rodin’s “Gates of Hell.” Rodin thought particularly of Dante’s warning over the entrance of the Inferno, “Abandon every hope, ye who enter here.”

What prompts me to write is a certain mood I have been in, and which I believe many others have been sharing. The word I would offer to describe this mood would be: foreboding. A certain apprehensiveness, unease, disquiet, dread. A feeling that something is about to go really wrong, wrong in a way it hasn’t before for most of us, or in a way we thought no longer possible. Or worse: that it has already happened; that the thunder was subdued if ominous, but the next lightning strike will not be, that it will disrupt everything about our way of life and about the possibilities for the future. I’m not going to bother now to try to give the reasons, or the facts of recent history, why I or we might think it is legitimate to feel this way. It’s the mood I want to reflect on, and to reflect on it in the way I’ve been educated to, that is, “philosophically.”

I don’t think there is a philosophy of foreboding exactly, but in pursuit of the foundations for one, I’d like, instead, to offer a few remarks about two other moods—which have more bona fide philosophical credentials—namely hope and despair. Philosophy hasn’t usually treated hope and despair as moods exactly. Philosophers usually don’t feel very comfortable talking about things that can be seen as largely subjective and potentially idiosyncratic like that. Philosophy has for the most part treated them more like quasi-“objective states”, by which I mean something like cognitive attitudes which have a kind of normative status. They are treated like states you ought to be in, attitudes you ought to have, or not. States or attitudes you can present arguments in favor of or in opposition to. These arguments and debates then result in the formation of two great opposing positions—meta-worldviews, as it were—Optimism and Pessimism.

The sense of foreboding I mention presents itself to me as a kind of waiting room. It’s a state of suspension open to overtures or assurances from either camp. It can either “fall” into pessimism or “steel itself up” and insist on optimism in spite of itself. Either side can take the high ground, insist that it is the “courageous” or “sober” or warranted response. Most public officials and figures have opted lately, at least publicly, for the magnanimous cloak of optimism. Every day, you hear people publicly pronounce that they are optimistic in spite of it all, even sometimes adding “now more than ever!” Our former president is a prime instance of this, and in the final words of his final press conference, he tried to assure us by saying, “In my core, I think we’re going to be okay.”

In reflecting on this, I thought of one of my favorite quotes from a philosopher. It captures the sentiment of suspension remarkably well and precisely. It was spoken by the Frankfurt School critical theorist Max Horkheimer at the annual meeting of the American Philosophical Association in 1946. The title of the lecture was “Reason against itself: Some Remarks on Enlightenment.” It ends with the following words: “The hope of reason lies in the emancipation from our own fear of despair.”

The thought here is presented as a beautiful Chinese box. What frames the outermost layer is the Marxist desire for and insistence on the need for emancipation. What becomes available through emancipation, however, is not exactly true human flourishing or a return to our un-alienated “species-being,”[1] but rather hope. A certain stance or attitude becomes warranted, justified, or legitimate. Hope of a particular kind…“hope of reason.” The phrase may strike us as odd, unfamiliar, ambiguous: is it “reason” doing the hoping; “reason” that is shackled, in need of liberation so that it may come to hope when before it was unable [“hope of reason” as “reason’s ability to hope”]? Or is it rather us, not wholly rational creatures after all, who are shackled precisely because we find ourselves unable to place our trust in reason anymore, unable to hope for reason as a vehicle of emancipation. Perhaps it doesn’t matter, or amounts to the same thing.

What is most striking about the quoted sentiment to me is its identification of what is doing the shackling. It is not despair that is the agent of imprisonment, not despair that keeps us, (or reason), in a state of unfreedom in need of emancipation; but rather fear. The problem is not despair, but our being afraid to feel despair. In other words, it is not pessimism that is a challenge to the liberating effects of rational hope, but our fearful dismissal of it. It is optimism itself that keeps us from achieving what optimism hopes for. Optimism is its own worst enemy; it is self-destructive. This is a breathtaking and bewildering sentiment: what enables hope, uniquely, is acknowledging the possibility that despair is actually the proper response, the proper attitude. This may seem hopelessly paradoxical; maybe it is simply incoherent, or rhetorically seductive non-sense, but I cannot shake the intimation that maybe it is also correct.

To begin to try to erode the sense of straightforward contradiction here, note precisely what is being asserted. It is not exactly that the way to be optimistic is to be pessimistic. It is that the only thing that could properly validate optimism [that is, make it a reasonable position to hold] is actively and consciously working on breaking down any psychological barriers we may have put in the way of becoming pessimistic. This is more coherent: what prevents our optimism from being warranted is our overeager adoption of it. The idea here is that there is a component to our unfreedom that is psychological, a kind of paralyzing phobia: fear of despair. This phobia creates a compulsive response—in Horkheimer’s words: a “self-imposed obligation to arrive at a cheerful conclusion.” Horkheimer’s suggestion: “To free Reason from the fear of being called nihilistic might be one of the steps in its recovery.” What we are going after, the state that might just prove to be emancipatory or liberating, is a suspended, liminal state—a state that is not yet optimism or pessimism, but which is primed for the latter as possibly the only way to validate or earn us the right to the former.

Let me take a step back. Horkheimer’s idea is that optimism can be self-stultifying. But why optimism to begin with? Where does it come from, this self-imposed obligation, this “compulsive effort to arrive at the cheerful conclusion”: this assuredness “in our cores” that “we’re going to be okay”?

Optimism was the characteristic mood of the European Enlightenment. Before the Enlightenment, Europeans tended to understand human beings fundamentally as “creatures of God” and human history as unfolding according to the Creator’s wise and providential plan. Such an omnipotent and benevolent Creator would guarantee that, at least for the “deserving”, everything would indeed be okay in the end. For the Enlightenment thinkers, it was humanity that was in charge of its own identity and destiny. Human beings controlled their own reality, and Reason was the instrument of control. This means: the power of Reason itself validated optimism, and made hope that the future will be better than the past the reasonable position to take. It legitimated the idea that human history itself was inevitably and ineluctably progressive. That human beings, through exercising their rational capacities for both moral and technological ends, were creating increasingly ordered, just, and peaceful societies where all human needs would be met and humans could be happy and flourish. The famous quote from Martin Luther King Jr. about the arc of the moral universe being long, but bending toward justice expresses this enlightenment confidence nicely.

So Enlightenment thought did not abandon or subvert the idea of Providence, so much as it rebuilt it on a different foundation. Providence at its core is the idea that everything happens for a reason, and moreover, that it happens for good reasons. There is a standpoint or perspective, indeed the most reasonable and clear-sighted and truthful standpoint or perspective, in which it makes very good sense for everything to happen just as it does, that it is for the best that it so happen. That it all must happen as it does precisely in order for everything to end up in the best possible way, or for all to be okay or right in the end. In other words, everything ought to happen just in the way it does. And Enlightenment does not give up on this, but rather doubles down on it.

In fact, one could argue that religion, or Christianity at least, got the idea from philosophy rather than the other way around. It’s really Plato’s idea. Many are familiar with Plato’s idea of Forms. Remember, though, that there is one Form that is “superior in rank and power” than the other Forms, indeed one Form on which all the other Forms depend for their very existence. Plato called this the Form of the Good, or Goodness itself, and grasping that was the true goal of philosophy.

If you remember the allegory of the cave in the Republic, the Form of the Good is represented by the sun outside the cave: the last and most difficult thing to be “seen” or grasped through reason. If the Forms represent the true nature of reality, the Form of Goodness is both the cause of and the way to grasp the true nature of reality. It provides the illumination that allows the other Forms to be seen or understood. So, beyond merely understanding the Forms of things, there is a final more complete understanding of them precisely in terms of their relation to the Good. In other words, complete understanding means understanding why things are the way they are, which means understanding why it is good that things are just that way and not otherwise. St. Augustine acknowledges Christianity’s debt to Platonism in a backhand way in the City of God. For Augustine, Plato’s Form of the Good essentially is the Christian God distorted through the lens of an incorrect theology. The shared idea is that the most rational, ultimate perspective on the world reveals precisely that the world is fundamentally good. Everything happens for very good reasons, so in the end, it’ll all be okay. Hope for the future is a very reasonable thing.

This is a core idea for one of the Enlightenment’s most prominent advocates and spokesmen, Immanuel Kant. He had very famously written that philosophy’s purpose was to answer three questions: What can I know? What should I do? and What may I hope for? Surprisingly, the question of the legitimacy of hope was right up there, as important, perhaps more important, to philosophy as the question of the legitimacy of our scientific and moral endeavors. Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason, as Plato had done before in the Republic, considers the question in terms of justice. Justice is something that Reason demands or requires. When Kant talks about “reason”, he means—quite justifiably I think—not just our ability to calculate and deduce, but also the capacity to try to make sense of the whole or the totality of things and events. Reason, he says, is only satisfied with “completeness.” When we try to grasp the world rationally, what we are trying to do is make sense of it all, as a whole, trying to understand how it all hangs together and presents a significant and meaningful totality. And as with Plato, things make rational sense when we can come to be able to see them as good. Things make sense to us when we understand that they have to be that way because it is good that they are that way.

For Kant, what reason expects and requires more than anything else is for the world to live up to a certain standard of justice. The most rational order is a just order, where justice is understood in terms of desert, that is, as everyone getting what they deserve. What reason then considers the “highest good,” the absolute best state of affairs, is the perfect correspondence between happiness and “worthiness of being happy,” or in other words, virtue. Justice means that good and moral people are rewarded with happy and full lives, and immoral and vicious people end up miserable.

This is of course palpably not how things seem to go here in the empirical world. In fact, it’s easy to get the sense that there is just no justice of this kind forthcoming; that it is quite alien to the natural order of things. If so, this would mean that the world-order—and subsequently, world history—ultimately just doesn’t make any sense. And Kant allows this as a possibility. For him, the only thing that could assure us that the highest good—the harmonic system of happiness and virtue—is even possible, especially given its absence in actual experience, is a “higher reason.” This higher reason is, again, God understood as the moral author of the empirical world. But once we have properly subjected human reason to critique, and located its proper limits, we realize that human reason alone cannot assure us of this. Human Reason cannot prove that such a God exists, or that each of us has an immortal soul that lives on after our bodies die away and thus can survive to experience the final and complete justice of the last judgment. But, crucially, because such justice is what reason requires in order to fulfill its essential vocation of making the world make sense as a whole, to give up on the idea of justice is to give up on reason. And to give up on reason is to give up on ourselves. We may not be able to know that there is a God who will ultimately make everything right, but we must nevertheless have faith that there is. And, astoundingly—and this is really where Kant’s originality and ingenuity lie—such faith is precisely then rational; Kant speaks here of rational faith and rational hope, and in some sense the point of his philosophy is to dispel the illusion that such terms are oxymoronic.

“Despair” by Auguste Rodin, 1890

Let me consider one last example. Kierkegaard’s guiding thought is a version of Kant’s: the impossibility of hope without God. For Kierkegaard, the source of all despair is the failure, or worse, refusal, to positively acknowledge “the actual power that has established the self.” This is God. But there are many stages along life’s way, and true faith—complete and total submission to God and his will—is necessarily the last and the hardest. The goal is to eradicate despair through the hope only faith can bring, but in order to achieve it, Kierkegaard suggests not that we reason ourselves into a relation with God, or the idea of God—as Kant had done—but rather that we first simply give in to despair. “Despair!” is the advice Judge Vilhelm gives the unnamed aesthete in Either/Or. Any life that isn’t fundamentally lived in submission to God is a life lived in despair anyway, whether it is lived in pursuit of aesthetic enjoyment, or in pursuit of fundamental ethical commitments. The problem is that both sorts of life unavoidably must involve various kinds of mechanisms for covering over despair, of distracting us from it. But such mechanisms cannot succeed forever, and in fact the mechanisms usually only serve to make things worse. So the advice is just to cut to the chase, to choose hopelessness. Despair is the necessary step to God, so being openly in despair is better than trying to fool yourself that you’re actually not; and in this sense despair takes you closer to God and to genuine hope.

I end with this example because it bears a striking similarity with Horkheimer’s apparently paradoxical advice: one must first countenance despair in order to earn the right to hope. Legitimate optimism can only emerge, if at all, from despair, that is, a loss of hope. But for Kierkegaard, the move from despair to faithful hope requires ceasing to rely on reason at all. His assumption of faith, as opposed to Kant’s, is precisely no longer rational or rationally justifiable. Hope is only ultimately secured by abandoning reason altogether.

So where are we left? Speaking for myself, and I assume for many others, the route to faith, and thus hope—of either the Platonic-Christian, Kantian or Kierkegaardian kind—seems closed off. Or at least none of them proves enough to fend off the current sense of foreboding. But I think the impulse and compulsion to hope is real as well. There really does seem to be a kind of reflex to try to convince yourself that everything will be okay in the end; I find it in myself too. And if what I’ve suggested is true, philosophy can offer some insight into why that is, where it comes from. To reiterate: The source of the psychological aversion to and fear of despair which threatens the legitimacy of Reason’s hope lies in the nature of reason itself. But this just seems to leave us, to borrow American philosopher John McDowell’s turn of phrase, only with “an exculpation where we wanted a justification.” Reason can’t help itself, perhaps, but that doesn’t make it right.

We are, I think, then still left with Horkheimer’s paradox. So let me, out of desperation perhaps, try to loosen and untangle the entire Gordian knot by pulling the knot more tightly. If reason is turned against itself—its optimism sabotaging its own progress—then perhaps the only way to save reason—the only way ultimately to be on reason’s side—is to try to subvert reason in this very particular way, namely by refusing its basic impulse toward optimism. Maybe the only possible way for things to turn out okay is if we accept that they very well simply might not, and so our only hope is to give up on the hope that they will.

***

Michael Stevenson is an historian of philosophy specializing in the German philosophical tradition from Kant to Heidegger, and is now a Core Faculty member at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. Educated at the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University, and Columbia University, he has previously taught at Barnard College and Hunter College, City University of New York.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.