Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid

An excerpt from Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid with an introduction by the author

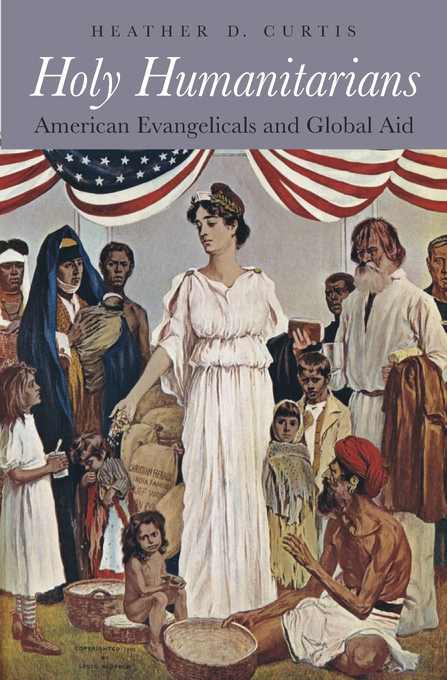

Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid (Harvard University Press, 2018)  explores how popular evangelical publications shaped American efforts to alleviate affliction at home and abroad at a time when the United States was extending its global reach through missionary outreach, economic expansion, and military imperialism. Focusing on the history of the Christian Herald – the most influential religious newspaper in the world at the turn of the twentieth century – Holy Humanitarians argues that evangelical journalism transformed American responses to domestic crises and foreign disasters during this pivotal period. By combining graphic accounts and gruesome images of suffering with biblical injunctions about almsgiving and long-standing narratives of American exceptionalism, the Christian Herald persuaded readers to see themselves, and their nation, as divinely-ordained and uniquely-qualified to save the world’s destitute, oppressed, and afflicted people.

explores how popular evangelical publications shaped American efforts to alleviate affliction at home and abroad at a time when the United States was extending its global reach through missionary outreach, economic expansion, and military imperialism. Focusing on the history of the Christian Herald – the most influential religious newspaper in the world at the turn of the twentieth century – Holy Humanitarians argues that evangelical journalism transformed American responses to domestic crises and foreign disasters during this pivotal period. By combining graphic accounts and gruesome images of suffering with biblical injunctions about almsgiving and long-standing narratives of American exceptionalism, the Christian Herald persuaded readers to see themselves, and their nation, as divinely-ordained and uniquely-qualified to save the world’s destitute, oppressed, and afflicted people.

During its heyday from the 1890-1910, the newspaper engaged ordinary American Protestants from across the United States in philanthropic efforts to assuage all kinds of affliction: from hunger and homelessness among New York City’s unemployed, or poverty and lack of opportunity among formerly enslaved communities in the American South, to disease and destitution among survivors of massacres in Armenia, warfare in Cuba, and famine, flood, or earthquake in India, China, Scandinavia, Macedonia, Japan, Italy, and Mexico. No other aid agency in this period – not even the American Red Cross – came close to matching the Christian Herald’s fund-raising record or ability to arouse popular concern for suffering within the United States and around the globe.

By analyzing the strategies the publication employed to inspire sympathy, collect money, and provide relief for victims of political violence, economic crisis, and natural disaster, Holy Humanitarians offers an account of how evangelical media and its consumers contributed to the development of American philanthropy from the late nineteenth century to the present. Excerpted below are several pages from the book’s introduction.

***

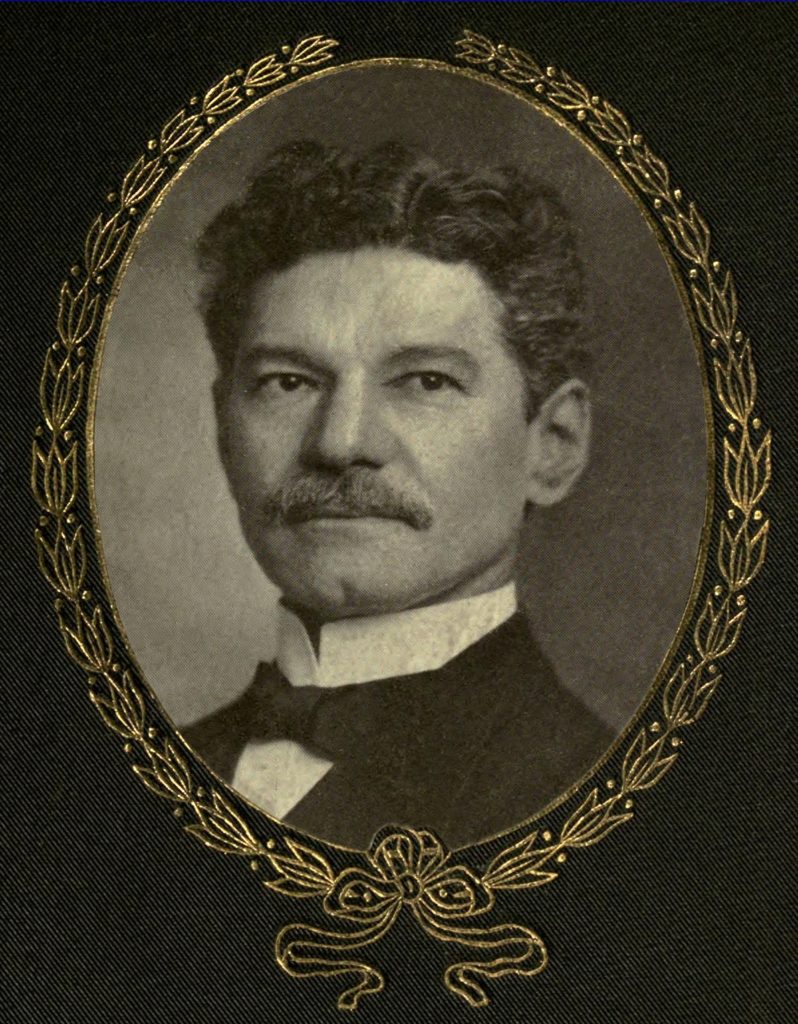

On a steamy summer day in July 1866, fourteen-year-old Louis Klopsch stood in the middle of the Beaver Street cigar shop in lower Manhattan, his body covered with blood and drenched in sweat. Just after he had opened the store for business, an excited Klopsch told his employer, four men had tried to steal a large quantity of cigars. Not “the kind of chap to let such a proceeding go on without a protest,” the boy attacked the would-be robbers with a piece of broken glass and a desperate fight ensued. Eventually, he succeeded in driving the thieves out. Although the store was a mess, Klopsch was unharmed; and his grateful employer offered him a “handsome sum” of twenty-five dollars as a reward for his heroism.[1]

Several days later, the burglars were back – this time in greater force. Undaunted, the courageous Klopsch grabbed a crowbar and beat the six intruders until he had “broken the skulls” of two men and chased them all off. Now, the shopkeeper became alarmed – perhaps these criminals intended personal violence against him. He called the police. When the investigators searched the premises, they discovered a suspicious sac that contained traces of blood hidden in the water closet. Putting this piece of evidence together with their doubts about Klopsch’s story, the police questioned the boy again. Realizing that he had been caught, the young man confessed to having “gone to a butcher’s shop, filled a bladder with blood, and, returning to the store, scattered it about the floor and walls.”[2]

The tales of the attempted robberies were entirely false. Klopsch was arrested on a charge of malicious mischief and after a brief incarceration released into the care of his physician father, who blamed his son’s exploits on drinking too much strong coffee and reading newspapers that filled his mind with imaginings. He “thinks to be something large,” the elder Klopsch lamented – like the characters he encountered in the “liar books” that an irresponsible aunt gave him to read.[3]

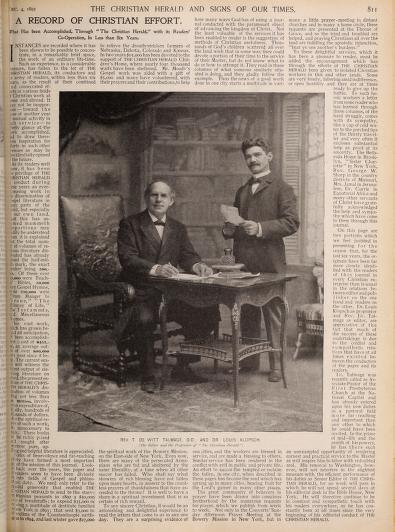

Despite his prodigal adolescence, which included several more run-ins with the law culminating in a two-year term in Sing Sing State Prison for forgery and insurance fraud, Louis Klopsch did become something large.[4] By the time of his death in 1910, Klopsch was hailed as “one of the historic figures in the annals of civilization” – a “friend of all humanity” whose “genius in the organization of benevolences” made him “the greatest inspirational force in the Christian homes of America” and “a blessing to mankind.” As a pioneer in pictorial journalism and proprietor of the New York-based weekly newspaper the Christian Herald from 1890 onward, Klopsch took advantage of new printing and photographic technologies to publicize humanitarian crises at home and abroad. By deftly coupling vivid images and graphic narratives of suffering near and far with appeals to biblical injunctions about almsgiving and deep-seated millennial expectations about the United States’ role as a redeemer nation, Klopsch induced readers to open their “hearts . . . hands . . . purses . . . and granaries” to “feed the hungry, to send or carry aid to the sick, and to spread the Gospel message everywhere.”[5]

With Klopsch at the helm, the Christian Herald became the most widely read religious newspaper in the world and “a chosen channel of individual and collective benevolence for the Lord’s people of all denominations,” raising millions of dollars for the suffering and needy of every land through a relentless succession of relief campaigns. For his work as “an almoner of nations in distress,” Klopsch was awarded the Kaiser I-Hind medal of the first class by King Edward of England in 1904 and decorated in 1907 by Emperor Meiji of Japan with the Order of the Rising Sun. His biographer described Klopsch’s life story as a “Romance of a Modern Knight of Mercy” that would inspire future generations of good Samaritans: “The voice that is silent yet speaks as with a thousand tongues through the good works that go on.”

***

Despite his extraordinary contributions to the fields of domestic charity and foreign aid, Louis Klopsch has been mostly overlooked by subsequent generations of philanthropists and scholars. Several studies do mention the Christian Herald’s involvement in international disaster assistance campaigns at the turn of the twentieth century, but few historians have recognized the newspaper as a major force in shaping the humanitarian sentiments and habits of the American public during this period of increasing globalization and United States expansionism.[6]

This omission results in part from the fact that the relief and development work of rival aid agencies such as the American Red Cross (ARC) and large philanthropic institutions like the Rockefeller Foundation eventually overshadowed the Christian Herald’s endeavors to assuage affliction. The copious archives of these competing organizations and their leading lights – celebrated figures such as Clara Barton, Frederick Taylor Gates, and John D. Rockefeller – have provided scholars with abundant materials for charting their participation in the development of American humanitarianism. Other than copies of the newspaper itself, several laudatory biographies of Klopsch and his associates, and a few accounts scattered in government documents or other periodicals, records of the Christian Herald’s remarkably effective efforts to engage American Protestants in massive international relief campaigns and a wide array of domestic charities have not survived.[7]

Louis Klopsch

Although this paucity of sources makes chronicling the Christian Herald’s seminal role in the expansion of American benevolence challenging, recovering this history provides a corrective to scholarly narratives that stress the increasing secularization of philanthropy during the Progressive Era. According to many studies, the rising influence of scientific authority and emphasis on professional expertise resulted in the decline of traditional modes of religious charity around the turn of the twentieth century. Some historians have argued that with the establishment of corporate foundations, the growth of the welfare state, and the development of the humanitarian aid industry in subsequent decades, alleviating suffering became the province of wealthy donors, government officials, and trained social workers rather than the responsibility of local congregations, benevolent organizations, or Christian missionaries. Furthermore, as the United States became more religiously heterogeneous, secular relief and development agencies gained an advantage over sectarian charities and eventually came to dominate the fields of domestic philanthropy and foreign aid.[8]

By telling the forgotten story of the Bowery Mission’s benefactor and his efforts to assuage affliction both at home and abroad, this book offers an alternative account of American humanitarianism. Examining the benevolent enterprises of Louis Klopsch and his colleagues illumines the fascinating but unfamiliar figures who fostered a tremendously popular faith-based movement with an enduring influence on the practice of philanthropy. Although the Christian Herald’s relief campaigns may have been eclipsed by massive charitable foundations, professionalized social work, and state-sponsored aid programs, the newspaper’s grassroots, volunteer, and unapologetically evangelical approach to relieving suffering has remained compelling among a considerable portion of the American population to the present day.

Shedding light on the role of religious media in shaping the development of humanitarianism thus elucidates how and why ordinary people have engaged in efforts to aid the afflicted. Because so many scholars have focused on the work of corporate charities or government agencies in providing assistance for those in need, histories of American philanthropy have typically emphasized the contributions of business tycoons, social elites, and political leaders in founding prominent institutions: Andrew Carnegie and his various foundations for the advancement of education; Jane Addams and her settlement work at Hull House; or Herbert Hoover’s missions to aid starving Europeans after WWI through the American Relief Administration. Some accounts have analyzed the intellectual influences of social gospel theorists such as Walter Rauschenbusch or economic philosophers like Richard Ely. This study brings into view a different cast of characters. Tracing Louis Klopsch’s transformation from duplicitous convict to “captain of philanthropy” and proprietor of the world’s premier religious newspaper shows how an entrepreneurial publisher, his enterprising partners, and a diverse community of readers from all across the United States and every walk of life participated in the making of popular humanitarianism during a transitional period in American history.[9]

As the account of Klopsch’s youthful escapades suggests, his spectacular success in arousing sympathy for the poor, the downtrodden, and the distressed is anything but a straightforward saga of heroic self-sacrifice for the sake of suffering others. Like many tales of benevolent campaigns on behalf of “those less fortunate,” this history exposes how instances of exceptional generosity have been bound up with personal self-interest and broader political agendas; how charitable engagement has been shaped by a mix of sincere religious convictions, shrewd business calculations, and complex cultural presumptions; how even the best intentions often produce tragic outcomes; and how the practice of philanthropy has always involved the exercise of prejudice, privilege, and power.

***

[1] “Police Intelligence,” NYH, 12 August 1866: 5; and “Alleged Embezzlement and Forgery by a Boy,” NYH, 21 January 1867: 7.

[2] “Police Intelligence,” 5; and “Alleged Embezzlement,” 7.

[3] “Police Intelligence,” 5; and “Alleged Embezzlement,” 7.

[4] On Klopsch’s criminal record, see “Essex Market Police Court: A Life Insurance Swindle,” New York Herald, 6 January 1875: 11; “A Swindling Insurance Agent,” NYT, 7 January 1875: 10; “Louis Klopsch,” Inmate Admission Registers, 1865-1971, vol. 12 (January 1875) 120, Sing Sing Correctional Facility Institutional Records, NYSA; and Registers of Commitments to Prisons, 1842-1808, vol. 6 (January 1875), Records of the Governor’s Office, NYSA.

[5] “Dr. Klopsch Laid at Rest,” CH, March 23, 1910, p. 275-277 and 299-300; “Our Departed Chief,” CH, March 16, 1910, p. 256; “The Whole World Loved Him,” CH, March 30, 1910, p. 321 and 328, “Starving India’s Pitiful Cry for Bread,” CH, April 4, 1900, p. 286; “Louis Klopsch, Almoner,” Outlook, March 19, 1910, p. 94; “Dr. Klopsch Laid at Rest,” NYT, March 10, 1910, p. 9; and Charles M. Pepper, Life-work of Louis Klopsch: Romance of a Modern Knight of Mercy (New York: Christian Herald Association, 1910), 327.

[6] The most thorough discussion of the Christian Herald’s humanitarian work may be found in Merle Curti’s American Philanthropy Abroad: A History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1963). Other studies that mention Klopsch and his associates include Julia Irwin, Making the World Safe: the American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013); Marian Moser Jones, The American Red Cross from Clara Barton to the New Deal (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013); Norris Magnuson, Salvation in the Slums: Evangelical Social Work, 1865-1920 (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1977); George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth Century-Evangelicalism, 1870-1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980); Keith Pomakoy, Helping Humanity: American Policy and Genocide Rescue (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011); Roger G. Robins, A.J. Tomlinson: Plainfolk Modernist (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Ian Tyrrell, Reforming the World: the Creation of America’s Moral Empire (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010); and Ann Marie Wilson, “Taking Liberties Abroad: Americans and International Humanitarian Advocacy, 1821-1914” (PhD diss., Harvard, 2010).

[7] Important works in this vein include Foster Rhea Dulles, The American Red Cross: A History (New York: Harper, 1950); Irwin, Making the World Safe; Jones, American Red Cross; and Inderjeet Parmar, Foundations of the American Century: the Ford, Carnegie, and Rockefeller Foundations in the rise of American Power (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

[8] Literature on the histories of philanthropy, evangelical charity, and humanitarianism in the United States is well-developed and too extensive to cite comprehensively. While some scholars have differentiated among these terms, especially as their meanings changed over time, Klopsch and his associates used them interchangeably. Works that chart a shift from religious charity to scientific philanthropy, professional social work, and/or secular humanitarianism include Elizabeth N. Agnew, From Charity to Social Work: Mary E. Richmond and the Creation of an American Profession (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004); Michael Barnett, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011); Jeremy Beer, The Philanthropic Revolution: An Alternative History of American Charity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); Robert Bremner, American Philanthropy, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); Peter Dobkin Hall, Inventing the Nonprofit Sector and Other Essays on Philanthropy, Voluntarism, and Nonprofit Organizations (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); Lawrence J. Friedman and Mark McGarvie, eds., Charity, Philanthropy and Civility in American History (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003); and Brent Ruswick, Almost Worthy: the Poor, Paupers, and the Science of Charity in America, 1877-1917 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

[9] Studies that focus primarily on elites include Bremner, American Philanthropy; James Kloppenberg, Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870-1920 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); and many others. Curti’s American Philanthropy Abroad and Tyrrell’s Reforming the World are exceptions to this trend.

***

Heather D. Curtis is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religion at Tufts University, where she also holds adjunct appointments in History, American Studies, and the Tisch College of Civic Life. Curtis received her doctorate in the History of Christianity and American Religion from Harvard University. She is the author of Faith in the Great Physician: Suffering and Divine Healing in American Culture, 1860-1900 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007) which was awarded the Frank S. and Elizabeth D. Brewer prize from the American Society of Church History for the best first book in the History of Christianity. Her recent book, Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid (Harvard University Press, 2018) examines the crucial role popular religious media played in the extension of US aid at home and abroad from the late-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. She is currently at work on a religious biography of Ida B. Wells. See heatherdcurtis.com for more details about her scholarship.

***

Excerpt adapted from Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid by Heather D. Curtis, published by Harvard University Press, Copyright ©2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.