Hindus Escape Pakistan’s Persecution, Only to Hit India’s Bureaucratic Walls

Although India claims to be a welcoming home for Hindus, Pakistani Hindus face legal and social hurdles when they try to immigrate to India

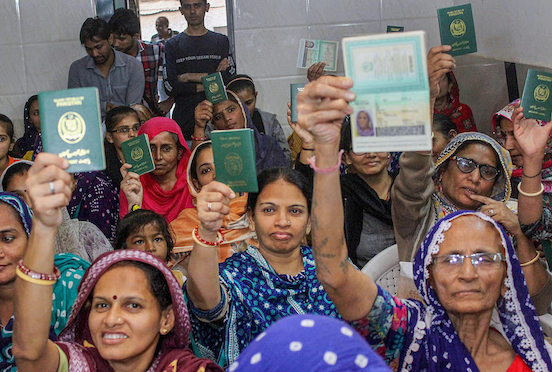

(Hindu refugees from Pakistan display their passports. Image source: The New Indian Express)

The desert city of Jodhpur in Rajasthan, India sits less than 200 kilometers from the Pakistan border, but for Samir Khan Manto* a Hindu who fled Pakistan, the distance is measured in years of fear. He left Pakistan almost fifteen years ago—leaving behind the spice trade his family had run for generations.

“In Pakistan, we earned just enough to eat—bas kamaya aur khaya—but we never moved forward,” he says. “No house of our own, no land, no education for our children. If you started doing well, the extremists would come for you. They would threaten you, extort you, make your life hell. Over there, we were called kaafir—non-believers of Islam.”

When the conversation turns to women, his voice tightens and he shares concerns that human rights groups have similarly expressed. “If you are Hindu there,” he says, “women are never safe. They [right-wing militias] will pick them up from the street—sometimes in daylight—and you cannot do anything. Girls are harassed and abducted going to school, so most families just stop sending them. If someone wants to take them, they will take them. You don’t even go to the police, because they won’t side with you.” He pauses, as if measuring how much to share, then adds quietly, “Many girls… they won’t come back. Sometimes you hear they’ve been married off to a Muslim man, their names changed, converted to Islam—and there is nothing their families can do.”

Rights groups in Pakistan have documented dozens of cases each year of Hindu and Christian girls abducted, forcibly converted to Islam, and married to Muslim men. One such case involved Pooja Kumari, an 18-year-old Hindu woman from Rohri, Sindh, who was shot dead in March 2022 by an extremist from the Lashari tribe after she refused to convert and marry him. Her family said they contacted the local police, but the officers “showed no interest” in intervening against the influential landowning tribe. More recently, in June 2025, in Shahdadpur, three sisters and their 13-year-old brother were reportedly abducted and forced to convert to Islam, a case that drew protests from minority groups but no convictions.

Pakistan is an overwhelmingly Muslim-majority country, with Hindus making up about 2.14 percent of the population, according to its 2017 census—barely over 4.4 million people in a nation of more than 207 million.

That makes the exodus of Pakistani Hindus to India all the more striking. According to Pew Research Center, around 500,000 Pakistani Hindus now reside in India, many fleeing kidnappings, forced conversions, and child marriages—sometimes involving girls as young as 12, activists say.

A 2018 Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) report flagged approximately 1,000 minority girls forcibly converted or married annually. HRCP’s own “Under Siege: Freedom of Religion or Belief in 2023/24 Report” underscores the escalation of kidnappings and forced conversions of Hindu and Christian women and girls, even as courts repeatedly accept dubious claims of voluntary conversion. The report also highlights that by October 2024, over 750 individuals were imprisoned on blasphemy charges. These laws, while ostensibly protecting religious sentiments, have been weaponized to target religious minorities, including Hindus, Christians, and Ahmadis. Accusations often stem from personal vendettas, land disputes, or as a means to suppress dissent. The mere allegation of blasphemy can be deadly: Dr. Shah Nawaz, accused of sharing blasphemous content online, was killed in a police encounter despite evidence of his innocence, while Muhammad Waris was lynched by a mob after being accused of desecrating the Quran.

Inside Pakistan, the state response is often dismissive. In 2020, the foreign office spokesperson, Zahid Hafiz Chaudhri, labeled forced-conversion allegations “fictitious [and] politically motivated,” while a proposed bill to curb forced conversion was blocked in 2021 under the claim it violated constitutional principles.

International pressure has also mounted. The U.S. designated Pakistan a “Country of Particular Concern” on religious freedom in 2021 and again in late 2023, citing United Nations experts “deeply troubled” by the rising horror of underage abductions, marriages, and conversions.

(Protestors march against the forced conversion of Hindu girls in Pakistan. Image source: Fareed Khan/Associated Press/The New York Times)

But while Hindus like Samir Khan Manto have escaped persecution in Pakistan, life in India offers no certainty. Pakistani Hindus in India live in the shadows, their futures shaped by legal ambiguity, bureaucratic delays, and no promise of citizenship. Families are often divided—some members crossing the border while others remain behind—leaving them without recognition, access to government services, or a stable life.

Despite India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, positioning itself as a “savior” of Hindus and promoting India as a refuge for persecuted minorities, there is no clear policy guaranteeing either citizenship or refugee status for those born in Pakistan. For many migrants, India has not been the safe harbor for Hindus that Prime Minister Modi and the BJP have promised.

Indian Citizenship Still Out of Reach

For nearly five years, Dhana Ram* scraped together the means to leave Pakistan. He is almost 30 now, living in India for the past seven years, but his journey began long before he set foot across the border. “Every visa application cost me around 400 to 500 U.S. dollars,” he says—a sum almost unthinkable for someone from his background. Twice, his applications were rejected. On the third attempt, he was approved. The money came from selling his small flock of sheep, and the only patch of land his family owned. That sacrifice brought him, his wife, his mother, and 35 other relatives to India.

Like many Pakistani Hindus, Ram arrived on a one-month tourist visa for pilgrimage—to Haridwar, Mathura, and Dwarka, cities that carry deep religious meaning for Hindus. But when the month was over, he stayed. At the local Foreigners Registration Office, he told officials that returning to Pakistan meant persecution.

Ram’s short-term visa was extended to a year, then to two. Now, like thousands of others, he waits for a Long-Term Visa (LTV)—the crucial step that allows legal work, access to government services, and a path toward citizenship. But the wait can be endless.

According to the Ministry of Home Affairs’ 2023–24 annual report, India issued 1,112 LTVs to Pakistani religious minorities in that financial year. But the numbers barely scratch the surface. Hindu Singh Sodha, president of the Seemant Lok Sangathan—an advocacy group for Pakistani Hindu migrants—says his organization has tracked over 10,000 LTV applications still pending, many for more than two years. “The number of LTVs issued compared to the number of applications is almost negligible,” Sodha says. “People are stuck in limbo.”

The Long-Term Visa is the single most important document for Pakistani Hindu migrants in India—their only durable proof of legal stay, and the key to unlocking a life beyond survival. Under the Ministry of Home Affairs’ rules, it is the prerequisite for obtaining essential identity documents such as the Aadhaar card—proof of both identity and address—and the Permanent Account Number (PAN) card, needed for opening bank accounts, accessing government programs, and securing formal employment.

Without it, daily life grinds against invisible walls. Ram, for instance, has still not been able to get an Aadhaar card. He works in a textile-dyeing factory in Jodhpur, a few minutes from the settlement where he lives—a job secured only through a relative already employed there. “You can’t find jobs easily in the city without Aadhaar,” he says. “They ask, ‘Who will assure that you’re not a spy from Pakistan?’” Word-of-mouth networks are often the only route to work.

The absence of documents traps people in a cycle of precarity: lower pay, no savings accounts, and little bargaining power. It also deepens the discrimination many already face for being Pakistani by birth. Migrants report being turned away from government hospitals without Aadhaar, and landlords in formal housing markets rarely consider them. As a result, many remain in informal settlements on the city’s fringes—the same marginal spaces where their first nights in India began.

The absence of an LTV doesn’t just limit access to jobs, housing, and basic services—it leaves migrants in a constant state of vulnerability, their legal right to remain in India never fully secured. That fragility was laid bare earlier this year.

In April, militants killed 26 people in India-administered Kashmir, in an attack the Indian government blamed on Pakistan. Retaliatory airstrikes followed, and tensions between the two countries spiked. Soon after, the Indian government revoked the visas of Pakistani nationals. Only those holding Long-Term Visas were allowed to remain. For thousands still waiting on pending LTV applications, the order carried the terrifying implication that they could be sent back to Pakistan. The directive was later eased, giving Pakistani nationals until April 27 to apply for LTVs, and clarifying that those with applications already submitted would not be forced to return to Pakistan.

Singh Sodha says the struggle is not only to secure LTVs, but to reach the final goal: Indian citizenship. Under the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019, religious minorities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—including Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians—can apply for citizenship, provided they entered India on or before December 31, 2014.

But this cutoff, Sodha argues, excludes thousands still fleeing persecution. “When minorities are being persecuted in the neighboring countries in almost similar ways, then why is there a cut-off date?” he asks. “If you’ve introduced the CAA in support of these communities, then why not also amend the visa rules for Hindu migrants accordingly?”

For those still waiting, the bureaucratic maze can be as punishing as the persecution they fled. Paperwork consumes years and drains what little money people earn. Jobs for migrants without citizenship are rare, and most survive on daily wages—the equivalent of less than $10 a day. Each visa extension, citizenship application, or change in documentation often requires travel to the capital, Delhi, or to the nearest Foreigners Registration Office. “Every visit costs money,” Ram says. “For printing, for processing, for travel. And on the days you go, you lose your wage.”

In the meantime, Pakistani Hindu migrants without citizenship are neither deported nor formally recognized as refugees. Instead, they live in a legal limbo, dependent on temporary documents, with the hope of permanency always on the horizon but never guaranteed.

Families on Both Sides of the Border

Even for those who have managed to cross the border after the long, expensive, and uncertain visa process, the anxiety does not end. It shifts from the fear of leaving, to the constant worry about those still left behind.

Manto, for instance, arrived in India with his brother, leaving behind three sisters — along with his brother’s wife and their two-year-old child. “We haven’t met them since,” he says. “They keep applying for visas every few months, but they are always rejected.” Once, his sister-in-law did get a visa approved—but by then her passport had expired, and the opportunity was lost. The cost alone makes repeated applications impossible. “It’s so expensive,” Manto explains. “When one person in the family gets through, nobody wants to miss the chance to come. But we can’t keep trying again and again.”

Thakur Sati Makwana’s* story is even more tangled. She came to India in 2018, leaving behind her newborn son in her mother’s care in Pakistan. Four years later, in 2022, she returned on a “No Objection to Return to India” (NORI) visa—a special re-entry permit that allows Long-Term Visa (LTV) holders to briefly visit Pakistan and then return to India. She went with her husband. The trip’s purpose was simple: to see her son. But when she crossed back, it was again without him.

But Parvati’s brief trip became a prolonged separation. Since returning in 2022, she has only seen her child on video calls. “I think I’m going to watch him grow up on my phone,” she says quietly. “I don’t know if we will ever be on the same side of the border again.”

According to Seemant Lok Sangathan (SLS), more than 800 people made the reverse journey back to Pakistan in 2022 (the most recent year of available data)—not because they wanted to, but because the years-long wait for Indian citizenship had ground them down, often leaving loved ones stranded on the other side. Sodha says such departures continue each year. “People wait for 20 years in the hope of settling here,” says Sodha. “By then, another generation is born—and still, they have no homeland.”

In the tense aftermath of the Kashmir attack, even the most basic contact became fraught. Video calls—once a lifeline for families split by the border—grew fewer, and for almost two months, they stopped altogether. “There was an increased scrutiny over all of us,” Sati recalls. “We didn’t want to keep calling our families and risk the Indian authorities or embassy thinking we were passing on information. No one told us to stop—but for our own safety, we decided to.”

As part of the retaliatory measures, both India and Pakistan shut down the Attari–Wagah crossing—the only land route between the two countries. Guarded by armed personnel and open only to those with special permits, the crossing had been more than just a checkpoint: it was a narrow corridor of hope, used by people to attend weddings, mourn at funerals, or simply see loved ones after years apart. Its closure turned that hope into a long, indefinite wait with no clear answer to when, or if, the gates will open again.

Life in India Is Not without Its Own Battles

Now, in Jodhpur, Manto lives in a cluster of tin-roofed shacks at the city’s edge, far from the life he imagined when he crossed the border. In his first months, he and his family slept on the rocky terrain of a shanty under the open sky. Slowly, they built a tiny home of stones and scrap tin sheets, a fragile foothold in a city that was not just unfamiliar but also unwelcoming.

“Even going to the hospital was a struggle,” he says. “If we showed our passport, they would see ‘Pakistan’ and call the police. People would stand ten feet away, refuse to let us come close, and wouldn’t hesitate to call us terrorists.” It was a reaction built on decades of distrust and animosity, rooted in the scars of Partition, repeated communal clashes, and a long history of political rhetoric that painted the “other” as a threat.

Sodha says attitudes in Rajasthan have shifted in recent years, with more people beginning to understand the persecution Pakistani Hindus have fled. But without proper documentation, daily life remains limited. No papers means no formal jobs, no rental agreements, no property ownership, no access to subsidized food, and no government healthcare.

In Jodhpur’s 23 settlements, most homes sit in informal colonies without sewage connections or municipal water lines. “We have a water plant nearby, but no pipelines,” Manto says. “We get piped water through the dying factory where I work—it’s the only way.”

The picture is similar in Delhi’s clusters of Pakistani Hindu migrant homes. Survival often means improvisation, but there are also glimpses of possibility—futures that were unimaginable back in Pakistan. Girls are in school. Young women are pursuing higher education.

Bhavani Singh, 19, is a national-level player of Mallakhamb, a traditional Indian sport involving acrobatics on a vertical rope or pole, and preparing to start a university B.A. program. She arrived with her parents 12 years ago, now lives on an LTV, and waits for citizenship. “I don’t think I would have ever been allowed to step outside the house there,” she says. “Here, our roads are still unpaved, our homes are thatched, but I know it will take me somewhere.” Her dream is to join the Indian Administrative Service, India’s top civil service department that shapes public policies across the country. “Just give me citizenship,” she says, “so I never have to fear being sent back to Pakistan.”

*Names with an asterisk have been altered to ensure anonymity.

Anuj Behal is an independent journalist and urban researcher based in India. His work explores the intersections of urban injustice, diaspora, migration, and climate change. His bylines include The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Nikkei Asia, Thomson Reuters, and more.