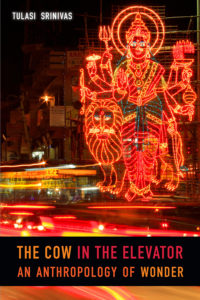

Hindu Ritual in India’s High-Tech City

A Review of Tulasi Srinivas’s The Cow in the Elevator

(Illustration of Bangalore courtesy of Plenty Facts)

Chapter One of The Cow in the Elevator: An Anthropology of Wonder opens with the eponymous scene. Author Tulasi Srinivas, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Emerson College, is cajoling a cow into an elevator. The poor bovine is afraid of the glass-walled enclosure that will transport her to the eighth floor of a brand new luxury apartment complex where she is about to play the starring role in a house-blessing ceremony (grihapravesham) for a million-dollar penthouse. The owners had hired a priest to perform this traditional ritual so the sacred cow’s presence would make their home suitable for habitation and usher prosperity into it. This is a scene played out across hundreds of elevators in hundreds of high-rise apartment complexes that now dominate the skyline of Bangalore—India’s high-tech city. With the help of a few ripe bananas, the cow finally makes it to the penthouse.

Elsewhere in the city, a construction site is undergoing a similar kind of consecration ritual. On the grounds of what will soon be another high-rise apartment complex, a local Hindu priest performs a ground-blessing ceremony (bhoomi puja), creating a small Vedic fire altar and – with prayers to Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth) and Bhoomidevi (the earth who is a goddess) – seeks the removal of bad spirits from the area. A developer commissioned this ritual at the request of construction workers who live in makeshift housing on the building site and work all day climbing bamboo scaffolding without hard hats or shoes. They refuse to work on sites in which the earth has not been ritually placated for fear that scaffolding might collapse or machines might malfunction, causing injury or death. All across Bangalore, amidst the constant throng of bulldozers and cranes making way for new construction, harried priests move from site to site with mobile phones practically attached to their ears as they fulfill overwhelming numbers of requests to consecrate land and buildings with prayers for safety, prosperity, or both.

In her stunning and provocative book, Srinivas draws on twenty years of fieldwork to highlight such stark contrasts of life in twenty-first century Bangalore. Some are astonishing, like cows in elevators, temples on Facebook, gods waiting in traffic, and giant robotic deities. Others are despairing or subversive, like the ritual taming of hazardous construction sites and land-grabbing gods. This rapidly changing urban space is thoroughly animated by rituals that have been transformed by modern materials and infused with the hopes and dreams—along with the anxieties and fears—of life in this unstable and unpredictable world.

In her stunning and provocative book, Srinivas draws on twenty years of fieldwork to highlight such stark contrasts of life in twenty-first century Bangalore. Some are astonishing, like cows in elevators, temples on Facebook, gods waiting in traffic, and giant robotic deities. Others are despairing or subversive, like the ritual taming of hazardous construction sites and land-grabbing gods. This rapidly changing urban space is thoroughly animated by rituals that have been transformed by modern materials and infused with the hopes and dreams—along with the anxieties and fears—of life in this unstable and unpredictable world.

The creative uses of ritual, Srinivas argues, allow priests, ritual specialists, and devotees to co-create moments of wonder that help them address the emotional valences of their lives, conjuring moments of awe in which they may dwell, at least for the time being. Srinivas focuses particularly on how ritual draws on the “techniques, tools, and strategies of capitalism” in order to resist capitalist projects. But as Srivinas observes, in many cases these rituals end up reinvigorating capitalist ideas and practices even as they seeks to resist them.

Srinivas focuses on the chief priests and devotees of two Hindu temples in the neighborhood of Malleshwaram. This was once a neighborhood of small middle-class bungalows interspersed with streams, man-made lakes, and rocky outcrops. Developers bulldozed it in the 1990s in order to make way for sky-scraping complexes and shopping malls that would cater to the new “global software workforce,” or as it is also known, the “boomtown bourgeoisie.” Over the past few decades, Bangalore has become home to Apple, Hewlett-Packard, and IBM, among many other multinational corporations (MNCs) after India relaxed restrictions on foreign direct investments. What was formerly referred to as “the garden city” is now the “high-tech city” or even “India’s Silicon Valley.” Malleshwaram transformed from a neighborhood characterized by nature, leisureliness, and what one former inhabitant characterized as “mood,” to one that is highly securitized, impersonal, and traffic-laden.

(Bangalore at night)

Like urban spaces across the globe, Bangalore is permeated by both heightened hopes and heightened anxieties. The gap between rich and poor is widening. Yet even the upwardly mobile find themselves – as Srinivas puts it – “plagued by guilt, doubt, fear, and greed.” They witness the poor around them getting poorer, even as they aspire for more wealth. And they worry that the wealth they have may be here today but gone tomorrow. MNC jobs pay well, yet they do not promise security of rank, salary, or even permanent employment as family businesses and government work once did. Against this backdrop, Srinivas shows readers that the ritual creation of wonder is not a luxury for her interlocutors, but a means of survival. It is a way to harness radical hope in a very uncertain time.

Each chapter of the book examines a different aspect of city living – new building projects, traffic jams, cash, technological innovations, and experiences of time – to explore how each opens up new possibilities for thinking about, experiencing, and creating rituals that recast modern living in a new light. Let me turn to some further examples to illustrate.

Early in the book, Srinivas discusses the “Dead-Endu” Ganesha shrine that mysteriously appeared on a triangular plot of land owned by the city. Like many other public spaces, that plot had fallen into neglect and was used for both littering and public urination. Now that people worship a divine being at that site, it will be incredibly difficult for developers to build on it. As Srinivas explains, developers routinely hire thugs to bribe city officials and intimidate homeowners in order to buy up city land. But few would ever consider demolishing a place of worship. Any building taking its place would inevitably be tainted by the specter of a displeased deity and accompanying bad sprits. In a city of constant landgrabs, citizens (along with their god) have grabbed land in their own subversive way with Dead-Endu Ganesha, thus exercising some control over the future of their city – or at least one small triangle of it.

(Advertisement for a “vastu” consulting service)

Meanwhile, inhabitants of the city’s new high-rise apartment complexes enlist ritual specialists not only to bless their homes, but to provide vaastu (traditional Indian system of architecture) revisions to existing housing. These rituals correct “bad vibrations” in the construction that have brought misfortune. At the “Golden Orchards,” for example, when the residents living on the West and South sides of the complex began to run into problems with their businesses, they hired a vaastu specialist who informed them that it was the servants’ entrances rather than the main entrances to their homes that were the profitable ones. Residents were pleased with this finding and hired construction workers to switch the entrances. In another example, a routine vaastu checkup revealed that a family’s home was arranged in a way that was bad for their health – the kitchen must be moved from the north to the southwest corner, the master bedroom repositioned, and all of the cupboards and closets shifted in order to allow for optimum energy flow and to produce a “comfortable” life. Among many other ritual options, vaastu assures them happiness and prosperity if their living spaces allow for the harmonious balance of energies.

In another example, Srinivas turns to a Ganesha temple in the same neighborhood in which chief priest Dandu Shastri collects colorful paper currencies from across the globe. He strings them onto garlands for the deity, displaying green American dollars most prominently. Shiny coins in silver and gold adorn Ganesha, the other deities, and the walls surrounding them. While it is customary in Hindu temples for devotees to offer the gods material goods including food, flowers, incense, and money, this kind of ornamentation by cash is highly unusual. Here, the glitz and shine of money creates wonder, eliciting “oohs” and “aahs” from temple visitors and producing a large increase in footfall. Is money being worshipped here? No, Srinivas concludes. She argues, drawing on Joyce Flueckiger’s work on the goddess Gangamma, that an aesthetic of excess demonstrates god’s power. Cash-clad Ganesha, she writes, mirrors the infinite possibilities and mysterious power that devotees want to see in their own lives. Devotees across the class spectrum marvel at the wealth of the gods and it gives them hope that god/s can make them wealthy too. This awe in the power of money along with the desire for more of it is wrapped up in a dharmic philosophy which claims that if you are rich, you must have been blessed by god and if you are poor, it is because of what you did in a previous life. But there is hope. No matter your dharmic past, god can help in the here and now.

Srinivas argues that this novel use of money at the temple is a way of resisting the capitalist order. By taking money out of circulation and using is as an aesthetic and even moral object, money is transformed into something the capitalist order did not intend. Ritual here disrupts the capitalist project not by rejecting it, but by capturing or using the very object to which that project aspires.

But some devotees are suspicious of the priests’ motives as they appear to be caught up in the same neoliberal processes as everyone else in the city. They advertise their temples and resident deities by employing flashy marketing materials – here, in the form of cold hard cash. Elsewhere, they attract devotees to their rituals by creating animatronic gods with glowing eyes and moving weapons, and by hiring flower-discharging helicopters. This is a situation critiqued by many who accuse them of greed and manipulation. Srinivas points out the great irony in such sentiments. The devotees engaging in and experiencing wonder through these rituals are all seeking higher-paying jobs themselves. They all want to live in nicer apartments and vacation abroad. And they all use marketing techniques to sell their IT products. They just don’t want the priests to do the same. They repeat the sentiment we find in American public discourse that wants religion to occupy a realm completely separate from that of economic exchange even though it never has and never can. Srinivas brilliantly uses this discussion to examine the limits of wonder. When devotees distrust the priests, the wonder they produce becomes ineffective. Wonder needs trust to work.

Srinivas’s experienced and eloquent prose gives this book a rare combination of provocativeness and accessibility. As a result, I have been able to share her work with my University of Oklahoma students to very productive effect. They have been enthralled by their exposure to Hinduism as it is lived on the ground in a rapidly changing urban environment. There are many aspects of this environment unfamiliar to my mainly Oklahoman and north-Texan students, provoking some difficult but fruitful conversations. The grihapravesham attendees’ excitement at a pile of cow dung – a sacred substance – on the marble kitchen floor of the penthouse, for example, elicited a long discussion of the differences between Hindu concepts of purity, auspiciousness, and cleanliness. Other aspects of Bangalorean life are familiar to my students. “That sort of development is exactly what is happening in my hometown,” one student from rural Oklahoma averred. “It’s so sad.” Everyone everywhere in our globalized world is familiar with the destruction of old lifeworlds making way for new ones. And the use – the necessity – of wonder in coping with that destruction and the ensuing uncertainty it brings made my students think concretely about what hopes and wonder replace what has been destroyed. Among sleek new megachurches and incense-filled yoga studios is the promise of new jobs and the assurance that one can be “spiritual” and deeply fulfilled by working in them.

The Cow in the Elevator provides an intensely real and nuanced account of urban life in the twenty-first century. It settles for no simple critiques of individuals or classes of people, nor any simple solutions to the difficulties of our times. It will be of great interest to anyone who sees the world changing around them and wants to learn more about how others deal with such change and imagine different futures for themselves. While hope prevails, so do systems that perpetuate individual anxiety and social inequity. The experience of wonder gives us hope, but it does not solve our problems.

Deonnie Moodie is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Oklahoma and a Sacred Writes/Revealer Writing Fellow. She is the author of The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City: Kālīghāṭ and Kolkata (Oxford University Press, 2018). She is currently writing a book about the recent emergence of Hindu ideologies in Indian business schools and corporations.

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.