In the News: Heavenly Bodies, Robot Funerals, and Kanye

A roundup of recent religion writing

First up this month, don’t miss, Randy R. Potts‘ What So Proudly We Hailed: A lens on the 147th annual NRA meeting for The Baffler

First up this month, don’t miss, Randy R. Potts‘ What So Proudly We Hailed: A lens on the 147th annual NRA meeting for The Baffler

Finally, after a short speech, and while he still stood at the podium, beaming, that song came on. You know the one. That Rolling Stones song that after two years has everybody trying to figure out why he plays it. Why would he not? Listen to the first two minutes on high volume. Imagine you’re standing in front of an audience who believes you are the Son of God incarnate. Angels, almost unintelligible at first, begin to sing. Then: “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, well you might find, you get what you need.” And then: a slow, mournful guitar. A funeral scene. It’s the last days. It’s a new era. Whatever pain you felt, well get over it. It’s not that your pain will go away. It’s that it doesn’t matter anymore. You’re going to keep hurting — a lot! — but it doesn’t matter anymore. Your pain is what you needed all along. Trump will make us all hurt, and he’ll laugh while he does it, and we’re in on the joke.

Next, let’s check in with some of our favorite other religion-related publications, Sacred Matters published an interview with Jennifer Garber about Colonial Violence, Sacred Power, and Gods of Indian Country

Next, let’s check in with some of our favorite other religion-related publications, Sacred Matters published an interview with Jennifer Garber about Colonial Violence, Sacred Power, and Gods of Indian Country

Broadly speaking, this book is situated within recent work about the cultural history of the concept of religion. The Americans in this book, which include Catholic and Protestant missionaries and reformers, invoked the word “religion” constantly, however their uses were slippery. Sometimes they meant a universal human impulse to connect with the supernatural. More often, “religion” served as a placeholder for their own particular traditions. Protestants, especially, talked about Indians’ need for “religion,” but meant a sort of generic Protestantism that Tracy Fessenden has so helpfully delineated. Every once in a while, some Christians living in Indian Country referred to Kiowa “religion.” Work by David Chidester reminds us to pay attention to such references. When did Americans call Native ritual activity “religious” and when did they withhold that descriptor? I track these usages (and their impacts) in the book.

And Mayanthi Fernando is guest curating a forum on Sex, secularism, and “femonationalism” at The Immanent Frame.

In their important new books, Sara Farris and Joan Wallach Scott examine how and why gender equality has become the basis for claims that Europe and North America are distinct from—and superior to—the rest of the world, and especially the Islamic world.

While Laura Kipnis also wrote about Joan Wallach Scott’s new book, this time alongside R. Marie Griffith’s new book, Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics in Letting Their Hair Down for The New York Review of Books.

While Laura Kipnis also wrote about Joan Wallach Scott’s new book, this time alongside R. Marie Griffith’s new book, Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics in Letting Their Hair Down for The New York Review of Books.

Whereas Scott faults secularism for not achieving racial and gender equality, R. Marie Griffith leaves you doubting that the United States ever achieved secularism. In Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics, she shows that at every turn in the culture wars of the last century or so, religious leaders have battled to obstruct gender, sexual, and racial equality, frequently with the cooperation of elected officials and the judiciary. Warring over birth control, censorship, sex education, interracial sex, abortion, and same-sex marriage, tearing their ranks and the country apart in the process, the antisecular factions clearly believed that the moral life of every American—and the body of every woman—was in their divinely ordained purview.

While we’re on the subject of gender, sex and religion, Kaya Oakes wrote about Forgiveness in the Epoch of Me Too for Killing the Buddha

We are in a peak moment right now when it comes to men asking women for forgiveness. And in each case, before any of the violations make it to court–which they rarely do–the forgiveness is meted out not by the judicial system, with its mythologies of checks and balances, but by the person who was violated. The onus for forgiving, over and over again, is laid at the feet of the victim. What are these men really asking women to do? To absolve them and clear their consciences, so they can move on. Meanwhile, the women are left behind to grapple with the repercussions of the abuse.

Ed Kilgore reported on #MeToo in the Pews: A Backlash to the Southern Baptist Patriarchy for The Daily Intelligencer

Tendrils of the #MeToo movement are reaching into unexpected corners of the patriarchal rock garden of American society. Most notably, a series of sexist and even violence-excusing remarks from Southern Baptist Convention theologian and former SBC president Paige Patterson is creating an unprecedented backlash in that famously conservative and politically incorrect faith community, the largest among American conservative evangelicals. Notably 2,500 Baptist women signed an open letter asking the overseers of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, where Patterson serves as president, to “take a strong stand against [his] unbiblical teaching regarding womanhood, sexuality, and domestic violence.”

And Sarah Seltzer wrote about Birthright Israel and #MeToo for Jewish Currents

As the #MeToo movement unfolded, Jewish Currents spoke with more than 50 Birthright Israel participants and staffers about their experiences with the often-fraught sexual and gender dynamics on the trips, uncovering the case above along with eight other alleged incidents of sexual misconduct ranging from verbal harassment to assault. The participants and staffers told us about a volatile mix of sex and alcohol that, as on college campuses, has the potential to turn toxic. In the cases of some incidents recounted to us, it did.

But many spoke of something more: a pervasive environment of sexual pressure that encourages Jews to meet, marry, and, someday, procreate with other Jews while being awed by the beauty and culture of Israel. This expectation is communicated before the trip even begins via official Birthright social media, and on the trips is expressed most directly around encounters between American women and Israeli soldiers.

Speaking of Israel, Nathan J. Robinson wrote about Israel and the Passive Voice for Current Affairs

In the United States, news reports from Israel often have something strange about them: People seem to die violently, but nobody ever seems to kill them. In 2014, when an Israeli missile destroyed a cafe in Gaza, blowing eight patrons to pieces as they watched a soccer game, the headlines in the New York Times were: “Missile at Beachside Gaza Cafe Finds Patrons Poised for World Cup” and “In Rubble of Gaza Seaside Cafe, Hunt for Victims Who Had Come for Soccer.” No word of whose missile it might have been; the missile seemed to have acted spontaneously of its own volition, and the hunt through the rubble seemed to be happening without anything even precipitating it. Just as reports on killings by police will claim that “A man died yesterday in an officer-involved shooting,” when the Israeli army kills Palestinians (as it often does), we read that “protesters have died.” The passive voice is the favorite rhetorical tool of propagandists worldwide, who “regret the mistakes that were made” without having to admit who made them.

Also on the subject, don’t miss this CBS News interview with Noura Erakat

And speaking of the passive voice, Blain Roberts and Ethan J. Kytle wrote about The Historian Behind Slavery Apologists Like Kanye West in The New York Times

According to a new Southern Poverty Law Center report on how slavery is taught in public schools, current pedagogy continues to focus on slavery from the perspective of whites, not the enslaved, while failing to connect the institution to the white supremacist beliefs that supported it. Textbooks often ignore slaveholders’ desire to make money and too easily slip into grammatical constructions — Africans “were brought” to America — that absolve enslavers of their actions.

While Ta-Nehisi Coates responded with I’m Not Black, I’m Kanye: Kanye West wants freedom—white freedom. for The Atlantic

It is the young people among the despised classes of America who will pay a price for this—the children parted from their parents at the border, the women warring to control the reproductive organs of their own bodies, the transgender soldier fighting for his job, the students who dare not return home for fear of a “travel ban,” which West is free to have never heard of. West, in his own way, will likely pay also for his thin definition of freedom, as opposed to one that experiences history, traditions, and struggle not as a burden, but as an anchor in a chaotic world.

It is often easier to choose the path of self-destruction when you don’t consider who you are taking along for the ride, to die drunk in the street if you experience the deprivation as your own, and not the deprivation of family, friends, and community. And maybe this, too, is naive, but I wonder how different his life might have been if Michael Jackson knew how much his truly black face was tied to all of our black faces, if he knew that when he destroyed himself, he was destroying part of us, too. I wonder if his life would have been different, would have been longer. And so for Kanye West, I wonder what he might be, if he could find himself back into connection, back to that place where he sought not a disconnected freedom of “I,” but a black freedom that called him back—back to the bone and drum, back to Chicago, back to Home.

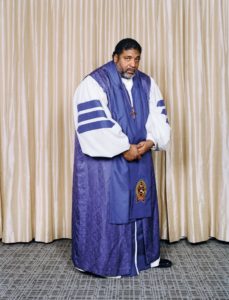

And one of our favorite historians, Jelani Cobb wrote a much more inspiring profile in William Barber Takes on Poverty and Race in the Age of Trump for The New Yorker

Barber speaks in a resonant baritone, with precise phrasing, but he is a true thespian of the pulpit: his eyes widen in mock surprise or squint in faux confusion at an act of outrage or injustice. Sometimes, after making a point, he whirls around, looking over his shoulder as if to see whether anyone has overheard him. From the balcony, he boomed, “We don’t need a commemoration, we need a reconsecration.” He had blown past the five-minute mark, but the crowd was with him. He warned, “The Bible says woe unto those who love the tombs of the prophets.” The duty of the living, he said, is not simply to recall the martyrs of the movement but to continue their work. “We’ve got to hold up the banner until every person has health care, we’ve got to hold it up until every child is lifted in love, we’ve got to hold it up until every job is a living-wage job, until every person in poverty has guaranteed subsistence.” He finished to loud and sustained applause. Shortly afterward, at a minute past six, the time that King was shot, an enormous bell in the motel courtyard rang thirty-nine times—once for each year of King’s life—and the crowd on Mulberry Street began to disperse.

Eboni Marshall Turman wrote, in memoriam, ‘If God Is White, Kill God’: Why Dr. James Cone Was Once the Most Hated Theologian in America for The Root.

Nevertheless, his fiery rhetoric and scathing critique of church, academy and society was a wake-up call to the entire Christian community. While some continue to disingenuously characterize his critique as angry, hostile and excessively harsh, what must never be forgotten is the depth of his love for black people.

Cone’s profound love and abiding joy for black life surfaced every time he stood in front of a classroom or put pen to paper or heard the spirituals and the blues. His love surfaced in his passion for black art and black dance, and his celebration of black excellence lived out loud in the face of white supremacy and its goons.

The most hated theologian in America built an entire disciplinary field. He authored more than 12 books and over 150 articles. He trained, chided and developed more generations of black theologians and black pastors than any other systematic theologian in the contemporary world. He taught us that God is black and that black is beautiful, baby. He did all of this because he loved us so.

And Churches make a drastic pledge in the name of social justice: To stop calling the police reports Julie Zauzmer for The Washington Post

And in far, far fluffier and more superficial church news (really, pretty much as far in the direction of fluff and superficial as we can get) the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute once again teamed up with Vogue magazine to host a giant party. But this year, the Vatican was on board and the outfits were, well, have a look for yourself here.

Rihanna at the 2018 Met Gala

For some background, Jason Horowitz explains How the Met Got the Vatican’s Vestments for The New York Times

Still, in a church where Pope Francis’s dressing down has made dressing up out of style, questions remain about how a lush exhibit and its related gala, organized by Ms. Wintour, squares with the pope’s desire for a less ostentatious, poorer church.

“Francis with his simple clothes expresses another concept. It’s not combative with the others,” said Cardinal Ravasi, who said he considered fashion a critical cultural language and the lent vestments expressions of the church’s power, beauty and splendor through the centuries.

Lilah Ramzi wrote about The Divine Inspiration Behind the Met Gala’s Floral Centerpiece for the gala’s host publication Vogue

“The tiara is the most striking component of the Pope’s ensemble,” Avila explained. “I wanted to depict a religious garment, given the theme of the exhibition.” The result of the laborious undertaking was resplendent, made up of 80,000 roses, color-matched to evoke the papal headpiece’s luminous gilt metal work with blooms in gold and silvery-white. Avila rendered the triple-tier tiara’s emeralds, diamonds, pearls, semi-precious stones with convex circles of jewel-toned plexiglass, “to capture the radiance of real jewels,” he explained.

And according to Kristi Upson-Saia at HyperAllergic, Early Christians Would Have Found the Met Gala Gaudy.

Were early Christians tapped to curate the fashion for the Met exhibition, they would showcase painfully coarse tunics that inspired reflection on and penitence for the sinful state of humanity; they would cover every inch of their model’s body to inhibit viewers’ sexual arousal; and they would highlight menswear. Were they asked to style celebrities for the Gala, they would likely advise them to skip the red carpet, trading the fame to be gleaned from appearances alone for merit earned through mundane acts of charity. Such piety would surely amount to sacrilege in the eyes of fashion critics and paparazzi.

But probably our favorite piece of writing about the Met Gala so far was Patricia Lockwood (and Her Mom) Talk Jesus, Fashion, and Who Wore It Best at the Met Gala over at The Cut

ME: Madonna?

MOM (in a snake voice): Madonna.

Meanwhile, Andrew Bui reports that Pope Francis Calls Pappy Van Winkle a ‘Very Good Bourbon‘ over at Tasting Table

And in other fashion, news, Ramadan Mubarak: “Black Panther” Has Inspired a New Trend in Ramadan Attire in Indonesia reports Steve Mollman for Quartz

Predictably, entrepreneurs have been selling versions of the shirt to Indonesians eager for their own. Vendor stalls in Tanah Abang, a sprawling market in Jakarta known for clothes and textiles, report high demand, and say they continually sell out of the shirts, especially since Ramadan began fueling demand. Even before Ramadan, which began last week, the shirts had been selling strong in Indonesia, appearing around the time of the film’s debut in February.

Lastly, how about a few notes on religion and technology?

According to Yomi Kazeem and Abdi Latif Dahir at QZ African cities are battling escalating noise pollution—but religion stands in the way

The pollution problem in many African cities goes beyond just the air quality.

Over the years, governments across the continent have attempted to tackle the noise pollution problem in major cities. In addition to the daily bustle and commercial activities, much of the noise comes from the thousands of religious places of worship that dot these cities.

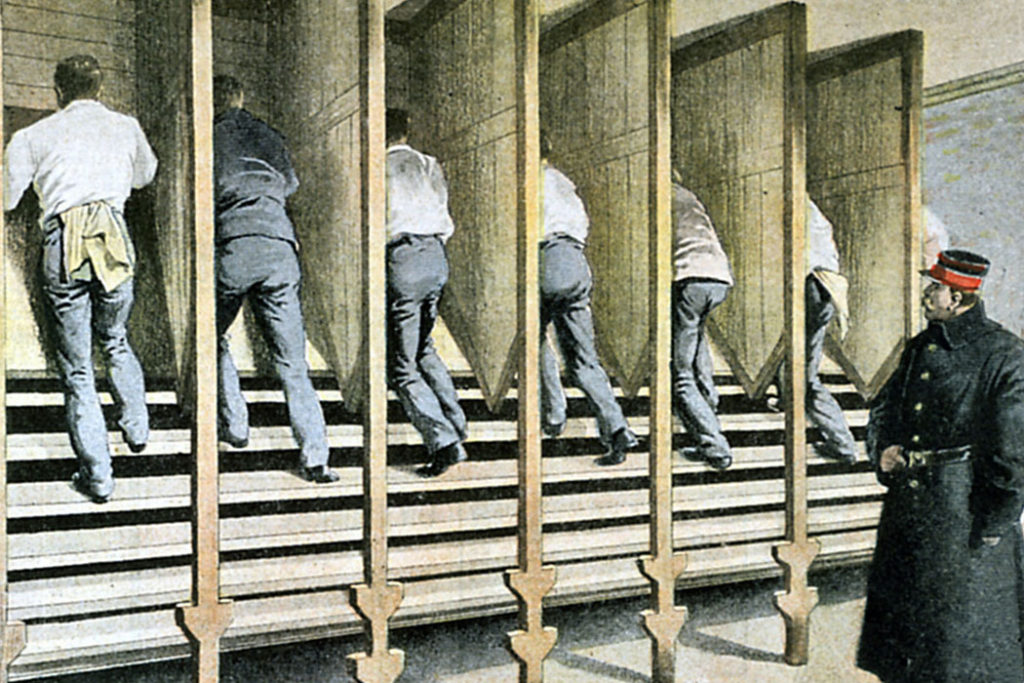

Also, apparently Treadmills Were Meant to Be Atonement Machines explains Diane Peters for JSTOR Daily

Inside of a century, the once-popular prison treadmill proved too cruel and pointless for its home nation, but that did not stop it from being imported to the U.S. The treadmill came to America in 1822, and was set up in four different prisons. It was briefly popular at the prison on East 26th Street in New York City. The first one installed there, which cost $3,050.99 to build, busied 16 prisoners at a time, who ground 40-60 bushels of corn a day. Within two years, the prison had built three more, two of them used by women. But, by 1827, the mills had fallen into only sporadic use and then were abandoned when the prison relocated. In Newgate, Charleston, and Philadelphia, treadmills were installed, used sparingly, and given up on in short order.

And finally, Japan: robot dogs get solemn Buddhist send-off at funerals reports Justin McCurry for the Guardian

Bungen Oi, one of the temple’s priests, said he did not see anything wrong with giving four-legged friends, albeit of the robotic variety, a proper send-off . “All things have a bit of soul,” he said.

And that’s all for this month. See you again soon!