Hate Male

A scholar of Indian history describes the dangers women academics can face when they share their expertise with the public

I have a folder on my laptop titled “Twitter, Facebook, and Gmail hate mail.” That virtual folder bears no measurable weight, but it has exerted demonstrable force in shaping my life as an academic over the last five years. Since the fall of 2015, I have received hate mail in response to my scholarship, which is primarily on sixteenth-century and seventeenth-century India, and my tendency to comment on modern Indian politics based on my knowledge of South Asian history. My insights about India’s diverse, multicultural past have aroused the ire of Hindu nationalists who claim that past to be monolithically Hindu in a brazen attempt to erase India’s rich Muslim heritage. The BJP, a Hindu nationalist party, has controlled India’s central government since May 2014, and they have pursued an aggressive agenda of transforming India from a secular democracy welcoming of all faiths into a fascist state meant for martial-minded Hindus alone. During the last six years, anti-Muslim violence has risen sharply, freedom of the press has declined ruinously, and universities have been subjected to relentless assaults. History is a primary battleground for Hindu nationalists who want to rewrite India’s diverse past to justify their present-day oppression and violence, and historians like me get in their way.

I have a folder on my laptop titled “Twitter, Facebook, and Gmail hate mail.” That virtual folder bears no measurable weight, but it has exerted demonstrable force in shaping my life as an academic over the last five years. Since the fall of 2015, I have received hate mail in response to my scholarship, which is primarily on sixteenth-century and seventeenth-century India, and my tendency to comment on modern Indian politics based on my knowledge of South Asian history. My insights about India’s diverse, multicultural past have aroused the ire of Hindu nationalists who claim that past to be monolithically Hindu in a brazen attempt to erase India’s rich Muslim heritage. The BJP, a Hindu nationalist party, has controlled India’s central government since May 2014, and they have pursued an aggressive agenda of transforming India from a secular democracy welcoming of all faiths into a fascist state meant for martial-minded Hindus alone. During the last six years, anti-Muslim violence has risen sharply, freedom of the press has declined ruinously, and universities have been subjected to relentless assaults. History is a primary battleground for Hindu nationalists who want to rewrite India’s diverse past to justify their present-day oppression and violence, and historians like me get in their way.

The vitriol directed at me has been amplified by my pursuit of public-facing intellectual work and my robust social media presence, two things many historians have pursued—and, often, have been encouraged by our mentors to pursue—with vigor over the last decade. My own experiences have resulted in three related sets of experiences as I navigate life as a public intellectual, manage relationships with colleagues, and produce scholarship. First, I am hated by a small but vocal group of Hindu nationalists, primarily based in India but also including a number of Indian Americans. This group attempts to marginalize my voice by subjecting me to a continuous stream of online harassment and threats. Second, as a result of these ad hominem attacks, many of my colleagues associate me with public controversy, and I must now contend with my reputation as a troublemaker. Third, the hate directed at me has changed my scholarship by constricting what I can and cannot say about premodern Indian history and to whom I might speak. In all three arenas, many people treat me poorly because I am a woman, and this gender bias has proved an intractable feature of my scholarly life over the past five years.

My story of being hated, known for being hated, and the pressures of dealing with that hate is unique in certain ways, as all stories must be, but layered sexism is something experienced to varying degrees by most female academics. Gendered hate harms not only the women targeted but the academy as a whole. If historians, religious studies scholars, and other humanities professors are going to share their expertise with the public in the social media age—and I think we should—then we need to talk about the hate that this earns some women and how it echoes through the sexism that continues to pervade the academy.

In addition to gender bias, we also need to talk about race and how many scholars of color are attacked and discriminated against in 2020. Women scholars of color often confront especially hateful opposition, in both the public sphere and academic circles, as they face racial and gender prejudices. I listen to the experiences of women professors of color. I try to put myself in their shoes while simultaneously acknowledging that I can never fully understand their position. I take active steps to contribute to the ongoing project of dismantling racial inequality on systemic and personal levels. I recognize that I need to do better.

For myself, I acknowledge that, no matter how virtuous my intentions, I operate as part of a racist world and benefit from white privilege, even while I face misogyny. This mix of privilege and disprivilege is one of many fraught factors that comprise my own experience of hate, which centers largely on gender. I share some of my experiences here as a way to explore one major problem in academic life, misogyny, with the goal of beginning to change the currently isolating experience of being a hated (female) historian.

Panoply of Hate

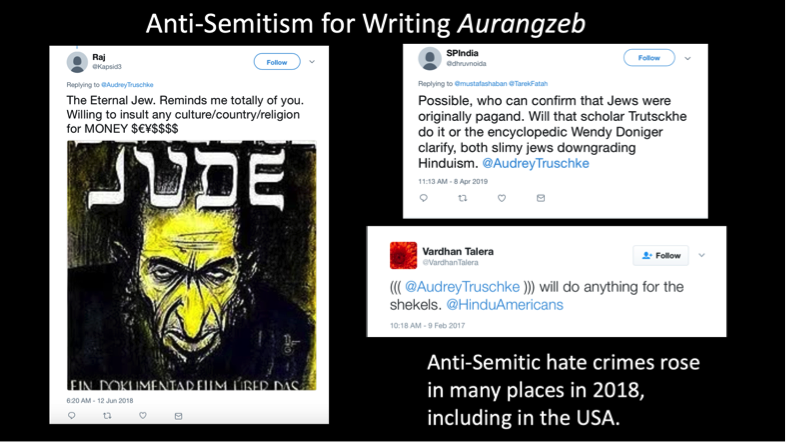

I received my first piece of hate mail in the fall of 2015 when I gave an interview about my book, Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court, to an English-medium Indian newspaper. This was one of my first attempts to speak to a non-academic audience. Shortly after the interview ran, I awoke to a tweet featuring a 1945 photo of Holocaust victims accompanied by the wish: “I hope another Hitler comes back and finishes off your people.” A web of alarming links bind together Nazism and Hindu nationalism, a political ideology that is separate from the broad-based religious tradition of Hinduism. Nazism served as an inspiration for early Hindu nationalists who saw Hitler’s treatment of the Jews as a useful model for how to treat India’s Muslim population. Even today, many Hindu nationalists remain unrepentant admirers of Adolf Hitler. That tweet in the fall of 2015 proved a harsh introduction to what can happen when women academics share their expertise with the public. A slew of vile tweets, Facebook messages, and emails soon followed, attacking me in gendered, racial, ethnic, and religious terms. At the time, I thought of that first wave of hate mail as an avalanche that could bury me alive. But compared to what I receive these days, I would describe those first messages as a trickle.

I currently receive hate mail, in descending order of frequency, via Twitter, Facebook, email, snail mail, and phone calls. Something comes in most days, and when I come out with new scholarship the hate mail can crescendo to hundreds of messages daily. Other people also receive malicious messages about me. I have had detractors email every colleague in my department to spread slanderous falsehoods. Both my graduate and undergraduate academic advisors have received rancorous notes about me. Groups have led coordinated attempts to pressure my university administration to retaliate against me and have called for my arrest upon arrival in India, where I travel for lectures and research. There is unflattering chatter about me most days on social media as well as appalling messages on WhatsApp, blog posts, and articles on Indian right-wing propaganda websites. At times, the assaults show clear marks of coordinated attacks that use paid troll accounts, bots, and right-wing networks to spread defaming claims on behalf of the BJP, India’s ruling party, and a dense web of Hindu nationalist organization.

I currently receive hate mail, in descending order of frequency, via Twitter, Facebook, email, snail mail, and phone calls. Something comes in most days, and when I come out with new scholarship the hate mail can crescendo to hundreds of messages daily. Other people also receive malicious messages about me. I have had detractors email every colleague in my department to spread slanderous falsehoods. Both my graduate and undergraduate academic advisors have received rancorous notes about me. Groups have led coordinated attempts to pressure my university administration to retaliate against me and have called for my arrest upon arrival in India, where I travel for lectures and research. There is unflattering chatter about me most days on social media as well as appalling messages on WhatsApp, blog posts, and articles on Indian right-wing propaganda websites. At times, the assaults show clear marks of coordinated attacks that use paid troll accounts, bots, and right-wing networks to spread defaming claims on behalf of the BJP, India’s ruling party, and a dense web of Hindu nationalist organization.

I was never trained to address anything approaching the savage animosity that is now directed at me in my daily life. I have written elsewhere about the larger political and social contexts, much of its concerning Hindu nationalism, in which I am subjected to vitriol. Here I reflect on the following questions that have occupied me for the last five years: How should academics deal with extreme levels of hate? What are the repercussions of being infamous for being hated, both in the public sphere and in the academic world? And, how does facing such hostility change one’s pursuit of scholarly knowledge? With few resources to traverse these frightening waters, I have cultivated a host of methods, to varying degrees of success, so I can share my expertise with the public while also dealing with a barrage of hate.

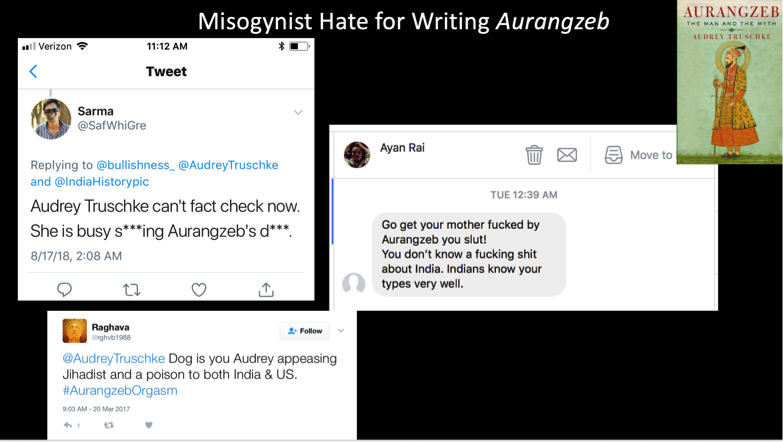

Object of Hatred

In what is the most quintessentially academic way to handle any problem, I analyze the hate I receive. I am targeted with anti-Semitic and anti-Christian messages, Islamophobic attacks, racially charged language, slander, and more. But, in my case, having a female voice seems to overshadow all other features, and so misogynist attacks constitute the most frequent genre of hate mail directed my way. I am regularly called a bitch, whore, prostitute, and presstitute (an Indian English term that combines “press” and “prostitute”). Some people revel in imagining me in sexually compromising positions, usually with Indian emperors who have been dead for centuries (yes, it is weird). Others prefer to belittle my intelligence in gendered language. I am commonly reduced to “woman,” my proper title of Professor or Dr. elided. When I point out the error, it usually has the effect of doubling or tripling the misogynist rhetoric in response.

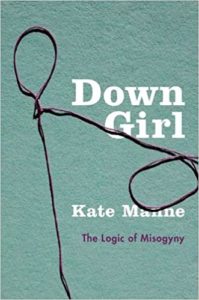

In making sense of this outpour of female-specific antipathy, I have found helpful Kate Manne’s insight in her book Down Girl that misogyny is not about hating all women but rather a set of attempts to control and punish outspoken women who challenge male dominance. My gender unlocks a range of deeply rooted, anti-woman attacks for those reacting to my audacity to speak-up. Such unrelenting attempts to compel female submission seek to tame me. Simultaneously, they work to dissuade other female academics from acting like me in the future. What woman wants to see vile comments about herself splashed all over social media? What woman wants her parents and children to see that?

Part of the cruelty of misogyny is that it dictates that women ought to feel embarrassed by being singled out for character smears. Writing this article is, among other things, an attempt to push back against this gendered way of feeling misogynist insults. It is the attackers who should feel shame, not the attacked.

Where possible, I use my own experiences to alert others about the dangers women face when we speak publicly. I regularly talk about hate mail in my academic lectures. In 2018, I was one of nine women interviewed in Amnesty India’s Campaign to address Online Violence Against Women. Disproportionate targeting of women is an appalling, well-documented aspect of social media, especially Twitter (here, here, and here). For the record, I have blocked over 4,000 Twitter accounts to date, but that still does not stem the tide of people insulting me with misogynistic language, threatening to rape me (and, occasionally, my daughters), and rooting for or promising to bring about my death. Twitter’s tolerance of misogyny has led to the deserved hashtag #ToxicTwitter and was one catalyst in the late 2019 experimental migration of many Indian Twitter users to Mastodon, a social media platform with a robust moderation system intolerant of hate speech.

Where possible, I use my own experiences to alert others about the dangers women face when we speak publicly. I regularly talk about hate mail in my academic lectures. In 2018, I was one of nine women interviewed in Amnesty India’s Campaign to address Online Violence Against Women. Disproportionate targeting of women is an appalling, well-documented aspect of social media, especially Twitter (here, here, and here). For the record, I have blocked over 4,000 Twitter accounts to date, but that still does not stem the tide of people insulting me with misogynistic language, threatening to rape me (and, occasionally, my daughters), and rooting for or promising to bring about my death. Twitter’s tolerance of misogyny has led to the deserved hashtag #ToxicTwitter and was one catalyst in the late 2019 experimental migration of many Indian Twitter users to Mastodon, a social media platform with a robust moderation system intolerant of hate speech.

There have been few upsides to being bombarded with hateful rhetoric, but one possible silver lining is that being a target of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim sentiments have, collectively, enabled me to gain deeper empathy for marginalized communities in India and elsewhere. Before 2015, I had never faced anti-Semitism for the basic reason that I am not Jewish. In the last five years I have been repeatedly misidentified as a member of a marginalized community subjected to alarmingly high levels of hate crimes in America, and, in the process, I have been thrown into a role I never expected to play. I am only thought to be Jewish on social media, which is markedly different from the lived experiences of many Jews. But even this highly limited environment in which people draw from the deep well of anti-Semitism in order to attack me in the most vicious possible terms has given me more robust awareness of the struggles many communities constantly face.

My empathy for Muslim communities, both in India’s past and present, has been enhanced by my experiences with Islamophobia. Because I analyze Indo-Muslim history, many see me as fair game for Islamophobic attacks. The rhetoric is appalling, often crossing over into dehumanization. Perhaps the most frequent accusation against me in the Islamophobic department is, simply, that I sympathize with Muslims. My bigoted detractors condemn compassion for any Muslim, but, as Professor Elya Jun Zhang recently wrote in a discussion of teaching premodern China, historical empathy is “one of the most important competencies our discipline can impart” that can serve “to bridge the gap between then and now.” I agree, and so, far beyond sympathy, I actively attempt to relate to Muslim communities, among other groups, in Indian history. I try to educate myself and others about the stomach-churning stream of anti-Muslim hate directed at modern-day Muslims, including Indian Muslims who comprise about 14% of India’s population.

I also extend empathy to the most unlikely candidates in this story: the haters. I view this, too, as an extension of historical empathy that, in this case, serves to diffuse my understandable anger and lends me insight into some key contours of the modern politics of Indian history. Many of my attackers believe that I am twisting their history, stripping away virtuous Hindu achievements and whitewashing demonic Muslim invaders. This perverse storyline of the Indian past (and my treatment thereof) is factually wrong, but many people genuinely believe it.

Two further facets make this modern emotional investment in a mythical, Hindu majoritarian-defined past something with which I can empathize. First, the West has a dark history of deliberately misrepresenting Indian history in order to promote the racist underpinnings of British colonialism. Given this, I can understand why some might be skeptical of a European-descent scholar who advances historical arguments that cut against the popular beliefs of many Indians. Two, few to none of my haters have anything approaching my level of academic training in South Asian history and in multiple premodern Indian languages. Among other things, this means that those who feel I am skewing their history lack the basic skills required to check my work or to formulate compelling counter arguments. The inability to engage on academic grounds is a major reason that political opposition to my scholarship takes the form of hate-filled attacks. Beyond the explanatory value of empathy, it is important to see the larger social inequalities and unequal access to education that, frustratingly, characterize our world.

Infamy Among Colleagues

Most of my colleagues—in the field of South Asian history and in South Asian studies more broadly—are aware that I face hate in the public sphere. When I meet colleagues for the first time, more often than not, they have already heard my name in connection with my reputation in this regard. Sometimes, this leads to good things. I probably receive more invitations to give lectures than I would otherwise. Many graduate students, especially young women, seem to find my experiences useful to reflect upon in the contexts of formulating their own career goals. But there are serious professional risks to my infamy in a male-dominated academic world that operates on personal connections and opinions.

Some of my well-meaning colleagues suggest that I and other targeted women should end the hate by going silent in the public arena. In fact, when I shared a draft of this article with colleagues, one responded by advising me to renounce social media to avoid further unpleasantness. Attacked women could, of course, retreat into the ivory tower by deleting our social media accounts, ceasing to write for popular publications, and only speaking to fellow scholars through paywalled academic articles. Taking these actions would reduce the venom significantly, or at least prevent me and other women from seeing much of it. But if we were to step back from the public sphere, we would do so at enormous cost to both ourselves and to the discipline of history.

Many historians use social media, especially Twitter, to speak to each other and wider audiences. Princeton professor Kevin Kruse, the most famous historian on social media, explained in a 2019 interview why he is active on Twitter: “Historians have a special expertise, a special knowledge about our past. And there are a lot of mistruths being spun about that in both the popular media and on social media. We have a duty to step in and correct those.” Kruse went on to say that he generally limits his fact-checking tweets to his areas of expertise, which is fine, because “there are lots of other historians on Twitter who are doing exactly what I am doing.” Kruse gave this interview at the annual meeting of the American Historian Association, the major U.S.-based professional organization in the discipline, which itself signals the importance of being on Twitter. The AHA regularly publishes Twitter handles in the bylines of articles in Perspectives on History, a monthly magazine sent to all AHA members. At its annual conference, the AHA offers to print four pieces of information on your badge: name, affiliation, pronouns, and Twitter handle. Asking women who face online harassment to walk away from Twitter is tantamount to asking us to forgo what has become, like it or not, an important medium in our discipline.

In the suggestion, no matter how well intentioned, that women ought to step back from social media when they are attacked, sexism is at work. The logic dictates that when a woman acts in a way that discomforts other people, she must change her behavior by going mute. As Kate Manne put it in Down Girl: “Silence is golden for the men who smother and intimidate women into not talking, or have them change their tune to maintain harmony. Silence isolates his victims; and it enables misogyny.” The result of a female retreat from social media would be to cede much public-facing history and its associated professional visibility to men, especially white men, who do not face similar threats and so have no reason to step back.

In the suggestion, no matter how well intentioned, that women ought to step back from social media when they are attacked, sexism is at work. The logic dictates that when a woman acts in a way that discomforts other people, she must change her behavior by going mute. As Kate Manne put it in Down Girl: “Silence is golden for the men who smother and intimidate women into not talking, or have them change their tune to maintain harmony. Silence isolates his victims; and it enables misogyny.” The result of a female retreat from social media would be to cede much public-facing history and its associated professional visibility to men, especially white men, who do not face similar threats and so have no reason to step back.

It is worth emphasizing that, in our society, men cannot be attacked in the same way as women. When you call a woman a slut, it carries a great amount of cultural baggage that evaporates when you apply the same term to a man. When you threaten to throw acid on a woman’s face (a threat I have faced), it is gendered; it is not similar to threaten a man using the same language. Unless we are resigned to declaring popular discussions about history and religion, once again, an old boys’ club, we must confront public hate against women as a problem impacting these disciplines as a whole.

Many of my male colleagues treat misogynist hate as a women’s problem, by which I do not mean a problem that disproportionately impacts women (which is true) but rather a problem about which only women need care (which is false). When I bring up my own tribulations on this score in conversation, some of my male colleagues look embarrassed, stare at their shoes, or squirm. It is as if I have just shared with them that I recently began my period, had a miscarriage, awoke drenched in perimenopausal night sweats, or some other comparable piece of female-specific information about which women whisper amongst ourselves as the need arises but is decidedly unwelcome in mixed company. What is rightly considered a field-wide issue—namely ferocious public pushback against female scholars—is reduced to being impolite talk, fit for women’s ears only.

Other colleagues blame me for inviting hate. They say I am too abrasive, too humorless, too self-righteous, or otherwise unfeminine in descriptions that, more than anything else, signal that many men still claim the right to dictate how a woman ought to speak. Pointing out the gendered, misogynist nature of such attacks risks igniting male resentment and anger. More than a few of my colleagues are willing to go to great lengths to deny the obvious: sexism persists in the academy, and women, especially outspoken ones, pay the price.

When there is a flare-up and I suddenly face an onslaught of public vitriol and hate, most of my colleagues remain silent. Many men and quite a few women fall into this category. Some watch the attacks online (many colleagues follow me on social media), but few publicly say anything about the waves of misogyny, bigotry, and ad hominem insults that crash into me. Perhaps many of my colleagues, men and women, forget that not speaking is also a form of communication. When you mutely watch a woman being relentlessly attacked with hate speech, your silence allows misogyny to do its dirty work of detaching and gagging female voices. I wonder sometimes if my quiet colleagues realize this, or if leaving the loud-mouthed woman out to dry is so deeply ingrained in our society that they do not even see their own complicity in isolating a woman as a means to discipline her into more demure behavior.

When I describe to my colleagues the hate that I face, some express sympathy. They tell me how horrible it is, or how sorry they feel for me. Some colleagues urge me to contact the police about the death threats, a perhaps well-intentioned show of interest in my physical safety that, at the same time, absolves them of any responsibility of further action. What is needed, however, is for scholars to transform their emotions of pity into an attempt to imagine walking in my shoes and, then, to analyze and discuss this horrifying, untenable situation that threatens key humanities disciplines. Humanities scholars are trained to extend empathy to people radically different from themselves (for historians, this is part of historical method), and so it is quite possible for my colleagues of all genders to exert energy imagining what it would be like to face unceasing misogynist vitriol. It is both callous and irresponsible to breezily dismiss blowback as the price that some women must pay. Instead, historians ought to talk, frankly and frequently, about how scholars experience attempts to present history to the public differently based on their gender, and then work to transform our misogynistic world.

Scholarly Risks

Being a target of contempt has changed my scholarship, sometimes in good ways. I find myself well positioned to write about a range of issues beyond premodern Indian history, including censorship, threats to academic freedom, sexism and misogyny, and current Indian politics. I also find that my reputation secures a relatively wide readership, both within and beyond the academy. I have many fans within this broad audience from whom I receive notes of encouragement and thanks. If only it was all so rosy.

Being subjected to ceaseless hate has also constricted aspects of my scholarship, both in public speaking and in print. This is painful for me to admit because this sort of influence—the ability of hate to shut down reasoned academic discourse—is, above all else, what I wish to prevent. To date, I have had one public lecture cancelled (in Hyderabad in 2018) because the organizers felt that a talk on premodern Indian history would be unsafe, for them and me.

Because people threaten me with violence, I am sometimes accompanied by armed security when I give public lectures about Indian history. When I spoke in New York City in April 2018, the hate mail had crossed into death threats and so an armed security officer stood outside of the room while I spoke about a twelfth-century Sanskrit text. In Chennai in January 2019, following an outburst by a visibly upset man regarding my scholarship on a seventeenth-century Indian king, I was again provided with an armed guard outside the lecture hall. The most extensive protection occurred in August of 2018 in Delhi. The venue provided airport-style security with a metal detector to screen those entering the auditorium and had plain clothed policemen scattered throughout the hall, “just in case,” I was told. A few days later there was an unsuccessful assassination attempt on a humanities graduate student in Delhi not far from where I had lectured.

There are practical questions about what risks are acceptable in order to speak about Indian history. Scholars must consider employment stability and the physical safety of themselves and their families. There is also the increasing risk of legal challenges within India, where Hindu nationalists seek to limit the circulation of scholarship. Wendy Doniger is a prime example; she faced a lawsuit for years over her book The Hindus: An Alternative History, which was dropped when her publisher, Penguin, agreed to withdraw the book from the Indian market and pulp all remaining copies. For women especially, the threat of sexual violence is also present. Cynthia Mahmood has written about her experience being gang raped in retaliation for pursuing a controversial subject while conducting research in northern India in 1992.

There are practical questions about what risks are acceptable in order to speak about Indian history. Scholars must consider employment stability and the physical safety of themselves and their families. There is also the increasing risk of legal challenges within India, where Hindu nationalists seek to limit the circulation of scholarship. Wendy Doniger is a prime example; she faced a lawsuit for years over her book The Hindus: An Alternative History, which was dropped when her publisher, Penguin, agreed to withdraw the book from the Indian market and pulp all remaining copies. For women especially, the threat of sexual violence is also present. Cynthia Mahmood has written about her experience being gang raped in retaliation for pursuing a controversial subject while conducting research in northern India in 1992.

I remain fuzzy about my own acceptable level of risk, and the limits are bound to be different for everyone. But I wonder if, by virtue of being a public intellectual, I have already ceded the ability to determine what chances I am willing to take. After all, I also exist outside of lecture halls and the classroom, and I am sometimes recognized in public. In 2018, I had a few young women approach me in Delhi and ask for a selfie. At the time, I viewed the incident as contingent on being in India, where I stand out because I am white. But then, in August of 2019, I spent a week hiking with my family in Acadia National Park in Maine. Acadia is so remote that I did not have cell phone service much of the time, but that did not prevent a gentleman from approaching me to ask if I was, indeed, Audrey Truschke. This time, too, it was someone who supported my work. While appreciative, I could not help but wonder: What if it had been a foe?

Sometimes I know that something I plan to say or publish will bring antagonists out of the woodwork. More often than not, I proceed anyway, in pursuit of public-facing history and with a desire to live an ethical life in which I use my platform and privilege to advance values in which I believe, such as human rights and widespread knowledge for all. But, other times, I too cave, and one such instance involves my second book, a biography of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir who died in 1707. I knew I was stepping into hot water when I decided to write about Aurangzeb, a historical Indian Muslim many love to hate. Aurangzeb serves as a dog whistle for Hindu nationalists who invoke him to rile up anti-Muslim sentiments and violence. I have detailed elsewhere how, acting on legal advice, I lightly censored the Indian edition of Aurangzeb in order to comply with Indian laws that restrict freedom of expression. I also cut all named acknowledgments and the dedication from the Indian edition out of a fear of reprisals and violence.

I chose not to name colleagues or family in the Indian edition of Aurangzeb because I thought that doing so might make those individuals targets of hate. This is a legitimate concern. In 2003 and 2004, vigilantes used the acknowledgements of Professor James Laine’s book Shivaji as a roadmap for people and institutions to attack. They literally blackened the face of one Sanskrit scholar whom Laine thanked in his book. A mob vandalized the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, one of Laine’s archives for the book and one of India’s great manuscript repositories. When I wrote Aurangzeb, I wanted to avoid repeating the targeting of helpful people and institutions that characterized the Laine affair. And, so, I scrubbed any trace of my support networks from the Indian edition of Aurangzeb.

I was never happy to erase my academic and personal contexts from Aurangzeb, but I recently experienced renewed outrage about the circumstances that made this a reasonable decision when I read Professor Emily Callaci’s article “On Acknowledgements.” In the piece, Callaci calls attention to how acknowledgements chronicle the exclusions and hierarchies that keep certain types of people out of the discipline of history. I agree with her arguments. But one line hit me in the gut in a way I do not think she intended: “Writing righteous, comradely acknowledgments is a great thing to do, but it also costs nothing.” I take Callaci at her word that this is true in her field of modern African history and probably in most fields. But acknowledgments are not always risk free for scholars of South Asia. Have I spent so long in a field crisscrossed by odious politics and looming violence that I have forgotten the normalcy enjoyed by my colleagues in adjacent fields, who can write acknowledgements in their books without thinking about who might be assaulted?

Reflecting anew on my decision to omit named acknowledgements and the dedication from the Indian edition of Aurangzeb, I was struck by how the harsh realities of my scholarly-cum-political world render isolation an outcome at multiple junctures. It is not reasonable, healthy, or sustainable to expect women to stand alone as they are bombarded by hate and threats in the course of sharing their expertise with the public.

Can we find a better, more supportive way for female scholars? I think we can, but it requires academics, especially men, to call out misogyny in the public sphere, in academic circles and in themselves. The three are connected since the gendered hate that other women and I face publicly is rooted in the desire to control outspoken women and maintain male dominance, which underlay our society, including academic contexts. Admitting the pervasiveness of anti-woman sentiments—and one’s own complicity in a sexist society—is the first step down the long road of dismantling misogyny, both in public and scholarly circles.

Audrey Truschke is Associate Professor of South Asian History at Rutgers University in Newark, NJ. She tweets at @audreytruschke. (For comments on earlier drafts of this essay, she would like to thank Dick Eaton, Simran Jeet Singh, Ananya Vajpeyi, and Taymiya Zaman.)