Hard to Love: A conversation with Briallen Hopper

Revealer Editor, Kali Handelman, interviews Briallen Hopper about her new book Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions

Kali Handelman: I feel like I have been eagerly waiting for this book for a long time — enjoying and commiserating and cheering on updates on social media, excited for a chance to revisit “Spinsters” and revel in deep thoughts on “Cheers” — and the book was all of the things I’d been looking forward to and so much more! I have lots of questions for you, but I’m going to try to keep them within The Revealer’s wheelhouse and ask you about the ways that religion and media figure into your book (goodness knows that both can, at times, be pretty “hard to love” themselves).

First then, as I just mentioned, the book is called Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions (Bloomsbury, 2019). “Confession” is a word that carries a heavy load — religious, legal, emotional. So, maybe this is predictable, but I’d love to know more about how you think of the relationship between essays and confessions. What separates the forms or makes them similar? What makes the book a collection of both?

Briallen Hopper: I love that “confessions” sounds both religious and salacious, like a book by St. Augustine and a scandalous True Confessions magazine. The word adds both gravitas and trashiness! Both these terms are in tension with “essay,” which seems more neutral (it could be the subtitle of practically any book of short nonfiction pieces), and maybe a bit more literary and cerebral.

Briallen Hopper: I love that “confessions” sounds both religious and salacious, like a book by St. Augustine and a scandalous True Confessions magazine. The word adds both gravitas and trashiness! Both these terms are in tension with “essay,” which seems more neutral (it could be the subtitle of practically any book of short nonfiction pieces), and maybe a bit more literary and cerebral.

“Confessional” is often used as an insult, particularly for women who write about themselves on the internet, so I wanted to reclaim it. In Hard to Love, I’m definitely being confessional in that I’m revealing private things that have felt shameful to me, like getting dumped and being a hoarder and losing a pregnancy. But I’m also trying to make something literary out of them–hence “essays.”

In retrospect, I do think writing the book had a personal purpose that might have been something like going to confession. I made myself face some of the hardest things in my relationships, and in the process I sometimes found some kind of absolution or made some kind of amends.

KH: You have more and less direct ways of talking about your own religious life in the essays, at times referring explicitly to your upbringing by “devout Calvinist convert” “religious hippies” and at others, more indirectly talking about prayer, church, and shrines in your adult life. I’m interested in how you chose to include the religious parts of your life, from your childhood to your own practice and religious education (and teaching and leadership) as an adult. There are, of course, shelves of books by people who were raised religious and left, but that’s not really what yours is. Which is all to say, I’m interested in how you choose to write about the role of religion in your life, and how your relationship to religion (belief, practice, community, knowledge, all of it) has and hasn’t changed?

BH: I once taught a class on religious memoir at Yale Divinity School, and I organized the readings by plot: Were they stories about growing up in a religious tradition, or converting to it, or leaving it, or returning to it, or staying in it? Over the course of my life, I’ve done all of the above except convert.

I was baptized in the Presbyterian Church in America, one of the most conservative evangelical Calvinist denominations, and I fled from from it as soon as I could. In my twenties I found a temporary refuge in a black mainline Presbyterian church in Princeton, where I stayed for seven years. It was the religious reeducation I needed. I’m currently a member of the United Church of Christ, colloquially known as “the last stop on the Jesus train,” though most Sundays I’m more likely to attend services at the bilingual Spanish/English Episcopal church in my neighborhood in Jackson Heights, Queens, and pray with my grandma’s Book of Common Prayer.

I think I kept the faith. The people I grew up with would say I left it. But whether I’m preaching Calvinism or ignoring it, it’s who I am. I couldn’t write a book about love without writing about religion, and my religious temperament is Calvinist. And actually I think a lot of the ostensibly non-religious parts of the book are actually a kind of stealth Calvinism!

If I were to phrase the five points of Calvinism in Hard to Love terms, they would be: No one can be or do anything good on their own, so you must find something to lean on. Receiving love does not depend on being worthy of it. Not everyone who wants a partner or children will get to have them. Love is strong enough to overcome our resistance to it. And, to quote the Spice Girls, friendship never ends.

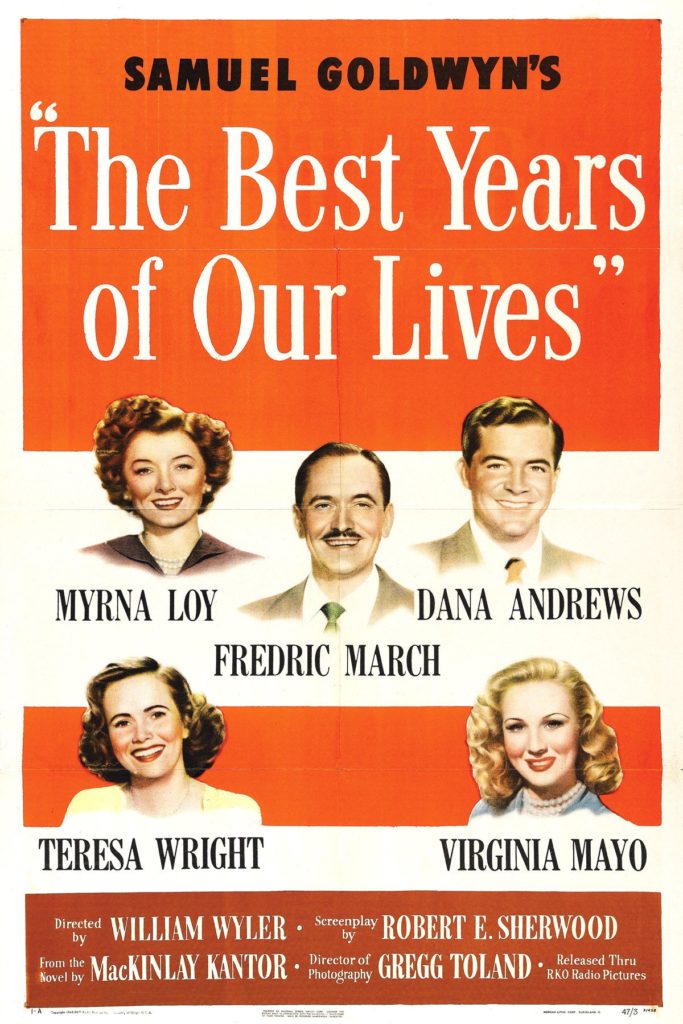

KH:You write in “Coming Home to the Best Years of Our Lives” that “I used to say that The Best Years of Our Lives” was like a religion to me.” Can you say more about what makes a movie, or a show (Cheers?) or actor (James Garfield? Paul Newman?) a religion? How do these forms of media become religion? (That may be the most Revealer question I could ask, I should probably just stop there, but I have so many more questions…)

BH: When I said The Best Years of Our Lives was like a religion to me, I think I meant, among other things, that it was a ritual practice; a source of meaning and identity; a foundation for ethics; a mode of connecting with others; a text I memorized and knew by heart; and also something unattainable, something always out of reach. A movie can be all these things.

And there are so many other ways for forms of media to become religion: ecstatic consumption, collective textual study, cultural edicts about what is or is not permissible to consume, the instinctive clutch of your phone in your pocket as if it were a handful of beads. I am here for them all.

KH: Similarly, perhaps, in many of the essays you have a central text (The Best Years of Our Lives, Hilton Als, a Gordon Parks photo, work by Shirley Jackson, Flannery O’Connor, The Fault in Our Stars, JD Salinger), you’re almost always reading something in your writing, and I wonder how you think about the role of these texts in your writing?

KH: Similarly, perhaps, in many of the essays you have a central text (The Best Years of Our Lives, Hilton Als, a Gordon Parks photo, work by Shirley Jackson, Flannery O’Connor, The Fault in Our Stars, JD Salinger), you’re almost always reading something in your writing, and I wonder how you think about the role of these texts in your writing?

Hopper: Maybe it’s because I’ve always been addicted to reading, or maybe it’s because I was trained as a literary critic and then as a preacher, but I rarely write an essay without depending on another text.

Sometimes my essays are a kind of love letter to the text in question– I think most of the essays fall into that category. Sometimes I’m celebrating or defending it (as with The Best Years of Our Lives), and sometimes I’m revisiting and questioning it (Franny and Zooey). Sometimes I’m rapturously meditating on it as a visual icon (the Gordon Parks photo of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, or the author photo of Grace Metalious on the cover of Peyton Place), and sometimes I’m returning to it as the site of a pilgrimage (the Foundling Museum, the Women’s March).

But sometimes the text is just an excuse. I don’t really care much one way or another about the Fey-Poehler movie Sisters or Kate Bolick’s Spinster. They just offered a timely hook for me to write essays on larger topics I already wanted to write about. I asked to review these texts without knowing anything about them apart from their titles, because knew that whether I liked them or not I could use them as foils for what I wanted to do. I needed to write in relation to something in order to know what I wanted to say.

KH: Another media question, but in a different vein: It’s clear that social media is important to you personally, for relationships and friendships, and also as a place to share feelings and opinions and stories. I’m curious how you think about your relationship to social media — it comes up a few times in the book (contrasting your family of origin’s comments on Facebook with your friends’ and found family’s), or when you talk about “complaining hyperbolically on social media.” Or, in another direction, but back to my first question, is there ever a relationship between posting on social media and confession for you?

BH: Absolutely yes. I share and overshare on social media as a way of dealing with being a social person who often comes home to an empty apartment. There’s a compulsion to tell and the need for a response. I can’t really imagine my life without social media. One Lent I gave up Facebook and it was one of the loneliest times in my life. I went from being in a fairly good place to fending off depression.

I also rely on social media for writing. My writing career literally started on Facebook. The first two pieces I published in HuffPost and the Chronicle started out as confessional Facebook notes which I then revised and expanded. Writing in general is very social to me, whether that means writing in a room with other people or posting paragraphs to social media as I write them– it’s nice to crowdsource ideas and get instant feedback as you put them together, and in the absence of people to write next to and among, social media steps in.

I know social media companies are evil, but I also found my agent and my job on Facebook, or more accurately they found me there, so apparently for me it’s a necessary evil.

Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward photographed by Gordon Parks

KH: Many of your essays are working through different questions about what American-ness is. I wonder if that’s an explicit theme for you and how you think about American-ness vis-à-vis religion and media?

BH: I sold the book in 2016 and was writing it as we made the transition to Trump, so I think it became much more of a meditation on Americanness than I’d originally envisioned it to be. But it became harder and harder to write about love and friendship as separate from national beliefs and calamities.

The first essay, “Lean On,” is a kind of manifesto subtitled “A Declaration of Dependence,” and it’s an attempt to resist the American cult of self-reliance that has done so much damage both to personal relationships and social policy. I do a kind of media analysis of representations of dependence and independence in film, TV, best-selling books, and popular music– from Bill Withers to Depends diapers.

One of the last essays, “Waveforms and the Women’s March,” tells the story of Trump’s Inauguration and the 2017 Women’s March through the lens of the Book of Exodus. There is obviously a long tradition, particularly in African American Christianity, of seeing American history through Exodus, as a story about slavery and freedom. My essay focuses instead on Pharaoh and the plagues, and how no one is coming to part the sea for us. I link media references to the oceanic feeling of the march to an ancient story about drowning and escape.

KH: I was really impressed by your ability to move between introspection and analysis about your own life — your feelings, choices, relationships, values, etc — and systemic social thinking about classism, sexism, racism, homophobia, settler colonialism and more. It’s a tricky thing, to, for lack of a better way of putting it, focus on working through your own shit, while also acknowledging your privilege and representing and reckoning with injustice. Can you say more about how you strike that balance in the book?

BH: I don’t really know how to work through my own personal shit, particularly in relation to love and friendships– which are always shaped by class, gender, race, sexuality, migration– without understanding it in relation to systems and history. For example, as I discuss in my essay on spinsters, in order for me to recover from a breakup in my twenties, it was essential for me to realize that my taken-for-granted ideas about romantic love were limited and distorted by my straightness and whiteness.

To be honest I’m not especially good at being aware of privilege or reckoning with injustice in personal relationships, as my friends and lovers would tell you! That’s what revision is for. Revising my writing, revising myself. I don’t see love as a refuge from these systems, this history. It is a reckoning with it.

KH: I work with a lot of academics who are interested in having public writing careers. You’ve clearly always written (notebooks, letters, academic work, sermons, lists), can you tell me a bit about how you started writing for publication, though?

BH: Honestly I started writing for publication because I first went on the academic job market in 2008, the year of the crash, and it quickly became clear I was not going to get a tenure track job anytime soon, if ever. And I was like, OK, I never especially enjoyed academic writing and now it’s professionally pointless, so why don’t I start writing things I actually want to write? And it turned out what I wanted to write was reviews and essays and listicles and op-eds.

It was very stressful to be a contingent writing instructor for most of a decade, but in retrospect, I feel lucky I didn’t get a tenure-track job in my former field of 19th-century literature, because although I did want to write about that literature, I didn’t really want to write about it in academic article or monograph form. When I was writing Hard to Love, It was a joy to be able to write about Emerson and Melville and Henry James and George Eliot in a totally different way. I always identified with the “scribbling women” of the 19th century who “lived by their pens” and wrote prose for the public, and now, hopefully, I’m becoming one of them!

KH: Lastly, and because I have the chance to ask, I have to ask: Your essay on hoarding may be my favorite in the whole collection (though I really don’t want to have to choose! All those sperm jokes in Moby-Dick! Heaven…), and, of course, as a Person of The Internet, I’ve been surrounded by (hoarding?) the Marie Kondo-ing of America this last month or so. Instagram posts of refreshed closets, thoughtful Facebook posts by scholars worried about the Orientalism and sexism running through the hottakes, hottake pearl-clutching about bookshelf purging, etc. So, basically, I just really want to know what — after doing so much thinking about what you keep and why you keep it — you think of the phenomenon?

BH: I’m so glad you liked the hoarding essay! I actually used it as the job talk for my current job, and I was like, hmm, outing myself as a hoarder to all my potential future colleagues is maybe a bit risky. But it still seemed safer than reading one of the essays about ex-boyfriends or sperm!

Anyway. Though I’ve read Marie Kondo’s first book, I haven’t yet seen the show. But even though I much prefer messy drawers to tidy ones (as you know, there’s a long section in the hoarding essay on chaotic drawers in Joan Didion and Marilynne Robinson!), I appreciate her approach to objects so much more than organization experts who focus on things like sanity, efficiency, and mental health. As someone who identifies as a hoarder, I resonate with Kondo’s unapologetic emphasis on “sparking joy” and on the magic of our relationship to objects, as well as her personification of them– the idea that you can thank them, say goodbye to them. It’s not an approach grounded in shaming or pseudoscience. It’s relational. It’s loving, in fact.

***