Hammams Then & Now: Changing Sites of Healing, Gathering, and Vulnerability

A critical historicization of bathhouse cultures

You may have many reasons for visiting a bathhouse in New York. Maybe you used to visit one in your home country. Or perhaps you visited a hammam on a vacation to Morocco, Turkey, or Spain, or heard a friend’s stories about their visit to one. Maybe you bought a Groupon for the Korean spa, or you go to the mikveh on Fridays. It’s possible you have a chronic pain or some other persistent physical discomfort, and some people in your family swear by a long sweat in intense heat, or rapid alternation between hot and cold temperatures. No matter what path or advice you’ve followed, here you are now, sweating and, perhaps, wondering about who is sitting next to you and why.

Hammams, bathhouses with rooms for heating, cooling and washing the body, have existed in much of the Middle East and North Africa since Roman times. After the advent and spread of Islam, the hammam, became something of a public resource, often built through charitable endowments by rulers or noblewomen in cities. It was – and remains – a place for people to bathe, get their hair cut, and achieve ritual purity according to the laws of Islam and Judaism.

Groupon image for a discount ticket to The Old Hammam and Spa in London

Bathhouses have been places of healing, gathering, and vulnerability for far longer than Groupon has been around. But, as many businesses continue to gentrify and whitewash the hammams for a new Euro-American clientele, this is a critical moment to step back and historicize them.

Most importantly, we should think about the norms and rules that have (explicitly and implicitly) governed bathhouse access and conduct. Those wishing to use these social, medical and religious spaces have been restricted – at different times and in different ways – based on gender, health, and sexuality. Thus, the bathhouse is a crucial site of sociality, and a key to understanding the shifting puzzles of power and culture over time.

The following vignettes take us through a range of notable moments in this long and complex history. From the concerns of Muslim jurists about forbidden erotic gazes and acts, to the imposition of French penal codes in the Middle East, to 20th century police raids. Hopefully, learning about these moments may help us think more deeply about how and why we enjoy bathhouses today. What our presence in these places means, and how it affects others.

***

Beginning in at least the 12th century, Muslim jurists wrote about the hammam as a place to be avoided when possible, where someone was always sure to catch sight of something or someone they shouldn’t, as a den of (potential) sin.[1]

The hammam in the Middle East was a place available to a broader public than most urban spaces, a place of work for many laborers with religious, medical and social functions. People visited the hammam for ritual baths after sex, menstruation, and birth, as well as for grooming, massages, routine bloodletting, or medically prescribed heating or cooling of the body. The jurists feared that the potential these uses presented for nudity and touching could incite the desire for sinful acts – between people of different genders and the same. But they also recognized that people needed a place where they could achieve the ritual purity necessary to perform their daily prayers. Thus, in their books, they made provisions for people of all genders (including those with nonbinary genders, khunthā) to enter the hammam, sometimes in groups or only at certain hours.

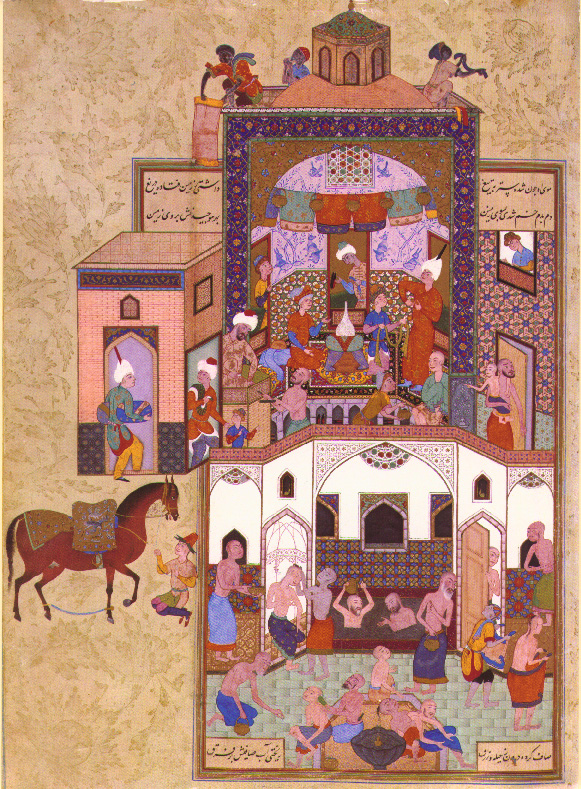

“Bath Scene from the Haft Awrang of Jami. Iran, Mid-16th Century (1556-65) 46. 12 FOL. 59. Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C.”

It is unclear if these jurists or their writings actually had much power to change the way that hammams were run, but we do have some evidence of ways that the government exerted its influence on hammams at the time. In one documented instance of the government attempting to regulate the behavior of hammam patrons from 18th century Aleppo, Ottoman officials attempted to ban Muslim and non-Muslim (dhimmī) women from bathing together. This attempt to exert control over their behavior and sexuality effectively rendered the Christian woman’s gaze upon Muslim women “male” – using pre-existing gendered distinctions to enforce religious distinctions. Such a division was clearly not common among users of bathhouses at that time, and as Elyse Semerdjian has observed, “the repetition of such policies also suggests that authorities may have had difficulty enforcing them.”[2]

The books written about the hammam that survive from the medieval period give us a sense of the concerns of certain groups in society, and how they may have attempted to change the social realities of patrons. Desire, passionate and sexual, was seen as a real possibility between people of all ages, genders, and religious identities, and the hammam was one of the few places where all of these people could mix.

***

The medieval jurists’ anxieties were not totally unfounded: within Islamicate[3] poetry, and Persian poetry especially, there was a general idea of the hammam as a site of erotic desire between men. It was a rare public space where people of all ages and classes could meet, from kings to barbers.

Stories set in the hammam usually ended up with someone in love, someone dead, or both. A lesson on love from the famous Conference of the Birds by twelfth-century poet Farīd al-Dīn al-‘Aṭṭār includes the following story: A great king, heart heavy with worry, left his palace to wander one night, when he came upon a man stoking a hammam’s furnace. He entered the man’s smoky hovel, and the man rushed to bring the king some old bread he had kept aside for himself. The king told him of his worries, and the man’s words impressed him so much that he returned seven times. During his last visit, the king cried out, “Stop your shoveling! You have no need of this. I am the king; ask of me what you desire.” The man said, “I have no desire to leave this place, because this place brought you to me. Rather than riches, or a place in your palace, my sole desire is that you visit me here, again.” The man stoking the fire (intended to represent the lowest of the low in society) held a love so pure that he did not want to dilute the pleasure of his beloved traversing distances both literal and social to see him. The story is also meant to illustrate that spiritual elevation can exist among the lowest classes of society, that social location matters little — but it is no coincidence that this unlikely attachment was formed in the hammam. The hammam was a place where the heart, and perhaps also the moral compass, was vulnerable.

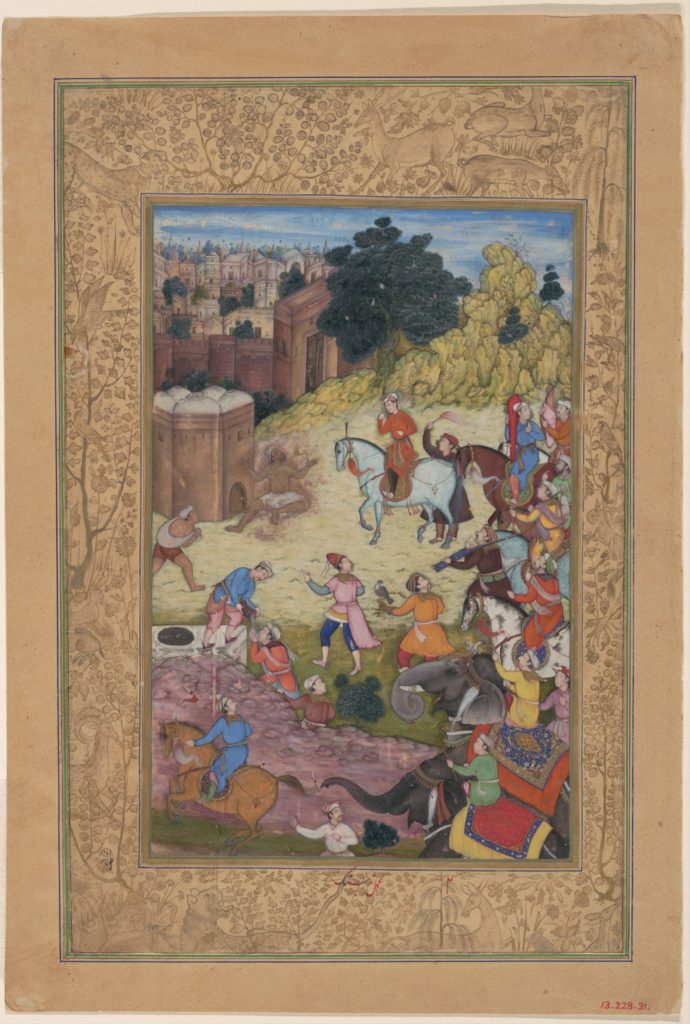

“A Bathhouse Keeper is Consumed by Passion for his Beloved”, Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

A century later, Al-‘Aṭṭār’s story about the wandering king was reworked by a poet, Amīr Khusro, in his Khamsa. In it, a beautiful prince passed by a man stoking the hammam, and their eyes met: the man fell in love. The prince turned away, but something in the worker’s eyes drew him back. Day after day, he rode by again, and the man’s love grew. One day, when the prince passed by and locked eyes with him, he burst into flames. Unlike the story in al-‘Aṭṭār, the love of the worker for the nobleman is not held up as an ideal, but as a warning — yet in both poems, it is taken for granted that the love is between men, at the hammam.

As hinted at in the Persian poems, the potential for the mixing of social classes at the hammam created an idea of it as a space for transgression, which coexisted alongside the reality of its boring, daily functionality for those living in the region itself.

***

Europeans coming into contact with the hammam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries focused on the erotic “homosociality” of the space and eroticized the image of the “harem” in the palace bathhouse. Though the average hammam in the Middle East was a place of work for many laborers, and a place with religious, medical and social functions, these hammams tended not to be the focus of European writers and painters. Rather, like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, they were more interested in places where royal or noblewomen went to bathe. She wrote:

If the painter “Gervase” (jervas) could look upon the bath, it would have very much improv’d his art to see so many fine Women naked in different postures, some in conversation, some working, others drinking Coffee or sherbet, and many negligently lying on their Cushions while their slaves (generally pritty Girls of 17 or 18) were employ’d in braiding their hair in several Fritty manners. In short, tis the Women’s coffee house, where the news of the Town is told, Scandal invented, etc.[4]

Montagu felt that the homosociality of the scene, which she likened to the almost exclusively male “coffee houses” of Europe, was worth emphasizing — even more so because of the ease with which patrons (if not their slaves or attendants) existed together in the nude. She focused on these elements knowing that readers would be most interested in seeing a room full of naked women lounging and drinking. These patrons are passive and idle — a scene closer to the idea of the hammam as “relaxation” we see marketed by businesses today than to the social, medical, and religious reasons that most patrons actually visited hammams at the time.

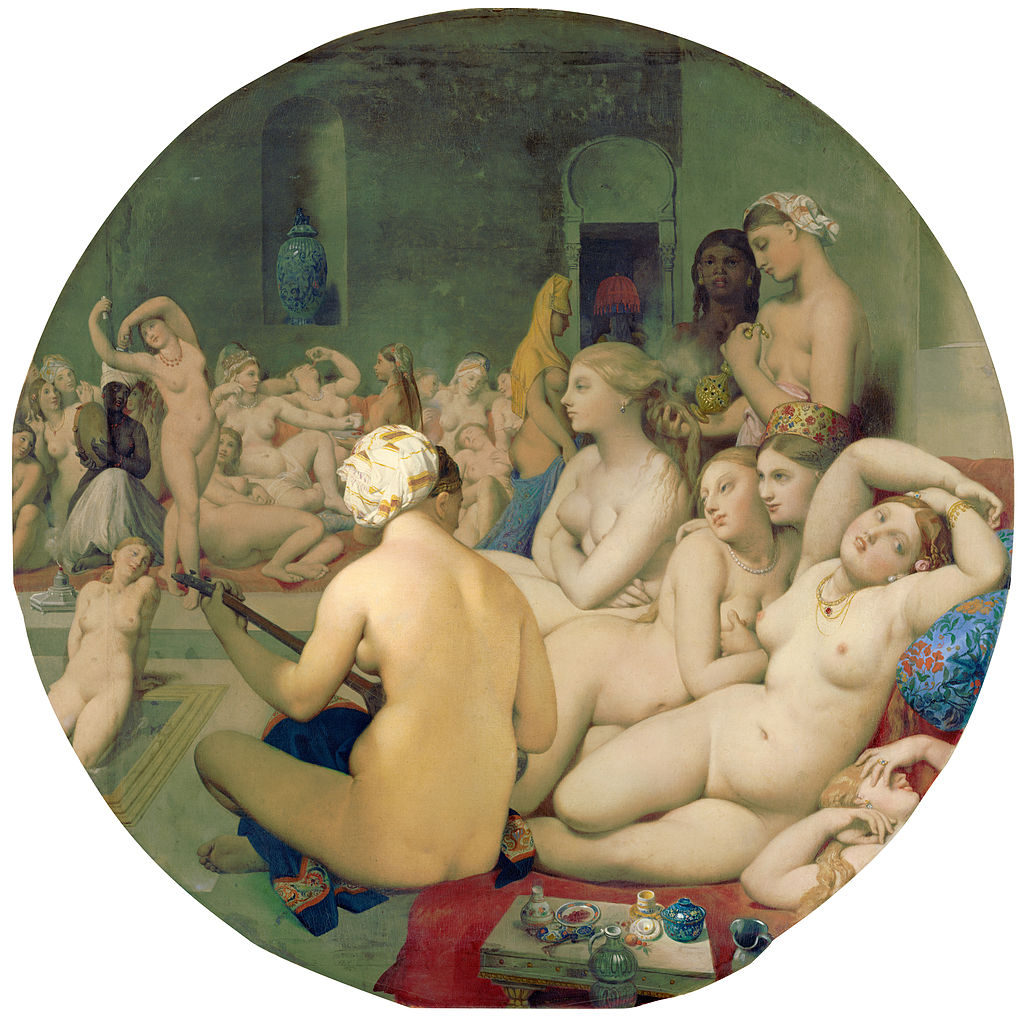

“Le Bain Turc” by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1862–63. Louvre, Paris

For hundreds of years, painter-adventurers depicted scenes inspired by passages like Montagu’s. Many painters, like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in his 1862 painting, “Le bain turc,” depicted his subjects with an erotic, voyeuristic and racializing male gaze. Things that usually appear in medieval paintings of the hammam are absent, like towels, pools of water, massages, haircuts and people washing themselves with buckets of water. Instead the women are all lounging totally or nearly nude, playing music, chatting or gazing into the distance. It is no wonder that Euro-American tourists today might find a neighborhood hammam, the kind used daily by people of all ages and body types, disappointing or unpleasant.

Orientalist depictions such as Montagu’s and Ingres’ tell us much more about what European travelers wanted from the hammam than they do about the bathhouses themselves. Yet it is these ideas that have gone on to shape the history invoked by businesses catering to Euro-Americans today. Thus, the hint at the erotic/exotic, offered by ancient massages in dim, steamy rooms is still tantalizing to their wealthy, cis-gendered target audience.

***

In the last century and a half some of the most prominent institutions of public bathing in North America have been gay bathhouses: both institutions founded for the gay community as well as some older institutions that started out as community establishments, often in Jewish and Eastern European enclaves, and then became known as openly welcoming to gay men. Public bathhouses were frequented for many reasons, though some like the Palace Baths or Jack’s Baths in 1920-30s San Francisco were known as gay cruising grounds. Many public baths at this time made reference to Eastern European cultures of bathing, including the Jewish schvitz or the mikveh. One of the first institutions to cater specifically to a homosexual clientele was called the Club Turkish Baths, which opened in the 1950s, in San Francisco. Though bathhouses did not always make reference to the hammam or Turkish bath, I’m sure that connection merits further investigation. In the 50s and 60s many such institutions opened in major cities in the U.S. and Canada.

We have record of police raids and attempts to close bathhouses from the 1890s onward. However, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 80s, the police, local governments, health departments, and citizens groups waged a large-scale homophobic campaign to close gay bathhouses. The gay bathhouse was transformed in academic discourse and public policy into an “epidemiological landmark for the transmission of HIV,” with recent public health literature debating whether they should be closed down or utilized as a site for HIV- and STD-prevention education. [5] Through the medicalized attention on these institutions, those few gay bathhouses that survive are now too-often sites of observation and regulation because of this history. And those bathhouses offering “treatments” or relaxation are shaped by this too – many make explicit in their rules that sexual activity is forbidden, and that patrons wear a specified amount of clothing during co-ed hours.

***

The hammam gained its reputation as a place for the low, dispossessed and/or depraved of society in the mid-twentieth century, as the wealthy gained access to indoor plumbing and in the wake of Egyptian films such as “Hammam al-Malatily.”[6] The film follows the moral and sexual corruption of a young Egyptian man from the countryside who comes to Cairo, and ends up living for free at a hammam with a sex worker and other supposedly disreputable characters. The idea of hammams as places of forbidden and socially threatening behavior remains relevant for those who still frequent them in the Middle East and North Africa today. Just a few years ago, police raided a hammam in Cairo and arrested 33 people, and the same year, 27 men were arrested at Agha Hammam in Beirut. In both cases, the police suspected the men of homosexual activity, which the colonial French legal codes established in both Egypt and Lebanon in the 19th and 20th centuries respectively had made illegal and punishable.

So, now perhaps you can see now how odd it might be to come across a Groupon offering “traditional hammam luxury.” Histories of exoticizing and othering, of eroticism and repression, have joined (ironically) uncomfortable forces in bringing such open access to these spaces for only certain people here in New York, today.

The “deviant” all-male sociality of the bathhouse, had to be suppressed or replaced in mainstream institutions. This older, taboo reputation has been white-washed and commodified. Now it is a product of the wellness industry leveraging its “ancient and authentic” past. The longer history of the hammam has been stripped of its medieval poetic resonances and any association with Islamic ritual, and has been repackaged for popular consumption.

The use of promotional websites like Groupon have encouraged some to experience new cultures of bathing, as at the famed Korean Spa Castle, and have created a new clientele for an older set of establishments, even when the facilities have barely changed. But with the exception of some single-gender hours once a week, all of these places are open to men and women. The image of the bathhouse as a neighborhood hangout for older men or a cruising spot for gay men of many ages has been pushed, once more, out of sight.

Despite the shifting gender dynamics of bathhouses, trans people are not explicitly welcomed in the policies of most institutions. Trans folks may have to spend hours on the Internet reading reviews, in hopes of finding a place to heat, bathe and cool their bodies comfortably, without fear of being asked to leave. Even at places in gayborhoods which have policies inclusive of all women, like HotHouse in Seattle’s Capitol Hill, some trans women have been turned away. Those who remember the bathhouse’s LGBTQ history in North America may feel excluded from the way businesses today are marketing themselves to straight, middle-class urban customers. And, one can imagine, that perhaps the business owners fear trans customers, and thus, intentionally exclude them.

As I visited bathhouses myself for my research, I often have had the urge to educate and remind those sweating around me about the long history that led to their moment of relaxation. It is not a linear narrative of progress that has led to the proliferation of gorgeous, expensive hammams in New York and many cities in Europe and North America. Let us not forget that non-binary people were able to enter hammams historically in the Middle East and North Africa, on the authority of Muslim jurists. Let us not forget that poets frequently imagined the hammam as the site of homoerotic love, across social classes. And when we picture the hammam today, rather the young, light-skinned women usually depicted in advertisements, let us remember the many people of all ages, genders and races who have and continue to visit hammams in and outside the West. Many of these people are going to hang out with their friends, or have pious motivations, and are visiting in preparation for prayer or holy days. Remembering these histories destabilizes the hammam’s increasingly prominent form as an increasingly exclusive and expensive commodity predicated on the absence of LGBTQ people and others who a white middle-class customer base could view as a sexual threat. It prevents the normalization of these curated absences and inaccessibilities, and the whitewashing of yet another history.

***

Author’s note: If you do support and enjoy modern bathhouses, then you should also consider supporting LGBTQ organizations that protect the vulnerable from being targeted in these spaces, both those in the Middle East like Helem, and those in North America.

***

[1] This was not true of all jurists, though. Al-Munāwī, a Muslim jurist who lived in Cairo at the turn of the seventeenth century, wanted to give the hammam a better image. Al-Munāwī thought that the hammam could be a place where Muslims strengthened their faith. He recommended that, when entering, visitors should let the heat remind them of the fires of hell, and the dim lighting of the darkness of the grave.

[2] Elyse Semerdjian, “Naked Anxiety: Bathhouses, Nudity, and the Dhimmi Woman in 18th-Century Aleppo.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 45, no. 4 (2013): 653.

[3] Marshall Hodgson used this term in 1974 in his famous book, The Venture of Islam, to describe things within the social and cultural world in which Muslims are a majority and/or politically dominant, but which are not necessarily related to Islam as a religion. The term is best used here because Christians, Jews and other non-Muslims also wrote Arabic and Persian poetry featuring the hammam.

[4] Srinivas Aravamudan. “Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in the Hammam: Masquerade, Womanliness, and Levantinization.” ELH, Vol. 62/1 (1995): 80-81.

[5] William J. Woods, Daniel Tracy, and Diane Binson. “Number and Distribution of Gay Bathhouses in the United States and Canada.” Journal of Homosexuality 44, no. 3-4 (2003): 55-70.

[6] See Mary Talmissany’s book on Cairene Hammams for more examples of the hammam in modern Arab cultural production.

***

Shireen Hamza is a PhD student in the History of Science at Harvard University. She completed her undergraduate degrees in English, Cognitive Science and Middle Eastern Languages and Literature at Rutgers University, after spending five years at an Islamic seminary in Karachi. Shireen is interested in the social and intellectual history of medicine in the medieval Islamicate world. Particularly, she is focused on travel and medical exchange between the Middle East and South Asia after the eleventh century, in Arabic and Persian.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.