Grief Reconfigured: Mourning Rituals and Interreligious Community Online

A virtual network for mourners in their 20s and 30s who are confronting grief in the pandemic

(Image source/creator: Jamie Edler)

Like so many others, Rachel Joseph said goodbye to a parent dying of Covid-19 through a screen. Her father, Sauveur, a pastor and retired plumber, fell sick during the pandemic’s first surge through New Jersey. He was admitted to the same hospital where Rachel’s older sister worked; he was intubated soon after he arrived.

“Going through this felt like a nightmare,” Rachel said. “There was literally nothing I could do to help him or see him in person.” She likened the experience to a horror movie. A boogeyman hides behind a door; their victim approaches impending doom, opening the door despite your vocal protests from the other side of the screen. “Of course they can’t hear you.”

Sauveur Joseph died of Covid-19 on April 12, 2020: Easter Sunday. Rachel heard the news over the phone, and then dropped it.

A thirty-three-year-old Black woman from Livingston, New Jersey, who works as an administrative director for Cornell University, Rachel Joseph describes church and family as her most trusted networks. She attends Hope Church Jersey City—its 90-minute services are a welcome reprieve from her father’s hours-long sermons at Grace Ebenezer Baptist Church, a Haitian Baptist Church in East Orange, New Jersey. Rachel plays the bass guitar as part of the Hope Church worship band.

With places of worship closed throughout the first months of the pandemic, and with a pell-mell patchwork of technologies rushing to fill the gaps, Rachel was left to grieve without the communities and religious traditions that would have otherwise buoyed and held her through the loss of her father.

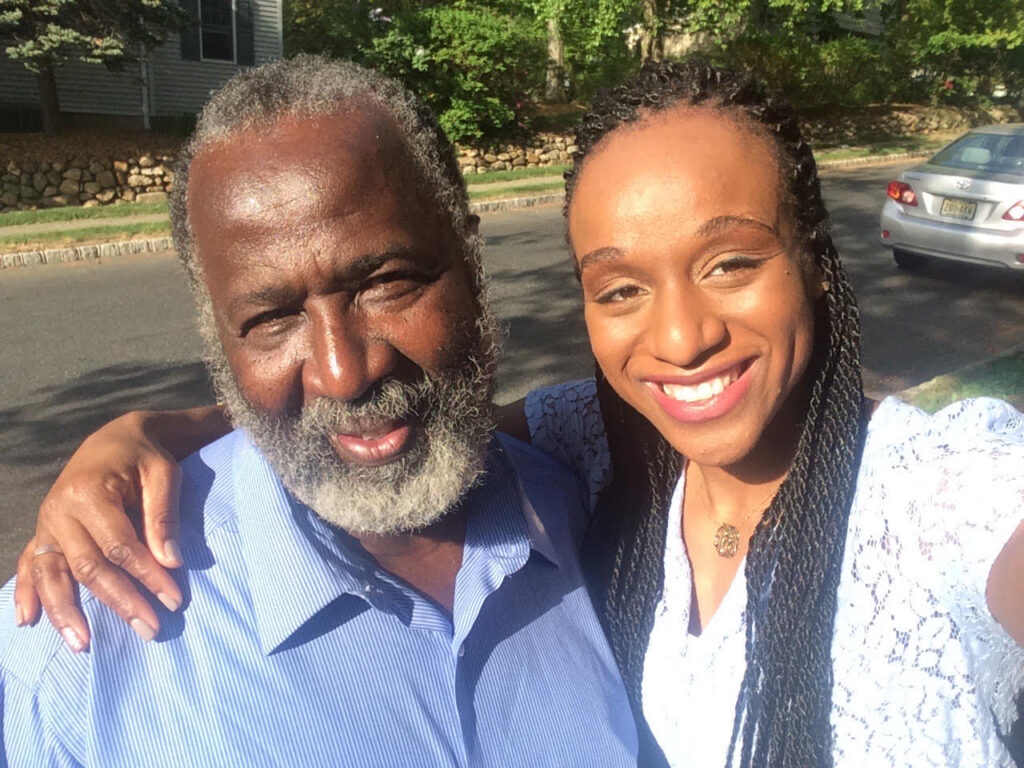

(Sauveur Joseph with his daughter Rachel Joseph. Image source: Rachel Joseph)

The pandemic forced people like Rachel to mourn not only the dead, but also the mourning rituals familiar to them. In turn, new models for mourning emerged as hundreds of thousands of people across the country confronted grief.

The Covid Grief Network, which integrates community organizers, spiritual care providers, and mental health professionals into a volunteer service for adults in their twenties and thirties who have experienced loss in the face of Covid-19, was a pivotal source of support for Rachel. Recognizing the racist and lethal effects of the pandemic, including unequal access to mental healthcare, the Covid Grief Network became an interreligious incubator for new and updated mourning rituals for grieving, marginalized people. Its members developed practices together, finding solace in cybernetic remembrance—sharing memories of a loved one with other pixelated, bereaved figures; noting the (liturgical) passage of time without the deceased; and silently meditating or praying before a Zoom room went dark.

***

At Sauveur Joseph’s service, Rachel and her relatives were forced to conduct a triage of their own. New Jersey public health officials capped funerals, even ones held outdoors, to ten attendees. Regulations also limited services to twenty minutes. Hugs were forbidden.

The family had to decide which relatives would attend Sauveur’s funeral in person. Rachel’s fiancé, Armando Sultan, a graphic designer, had developed a strong bond with Sauveur over hours-long theological conversations. He had to wait in the parking lot to make space for other family members at the funeral.

The funeral home lacked a WiFi connection, so the Josephs relied on a mobile hotspot for a Zoom-based funeral service. But cell-phone signal was spotty. The pastor for the funeral—who Zoomed in—delivered his remarks in patches. The audience witnessed a garbled, blurred funeral, while the Joseph family wrangled a frustrated, confused mass of spectators who sat on a screen. And then the Zoom room reached capacity, shipping scores of mourners to a purgatorial, virtual waiting room.

“I do not wish this on anyone who has a loss in their family,” Rachel said. “We had to rush through our grief.”

***

The notion of an exclusively virtual funeral is a “myth,” according to Dr. Tamara Kneese, a scholar of technology and mourning. The mortuary process doesn’t become more convenient through digital forms; family members and traditional figures still have to negotiate with a real-life corpse, regardless of the funeral’s ultimate venue. Yet, with the pandemic, crucial ancillary moments died off as physical grieving spaces closed and loved ones could no longer share food or hugs.

Kneese identified the technological management of Zoom funerals as a relatively new, and therefore potentially alienating, grief ritual. “These are not things that we’re used to having a strong attachment to,” she said.

Ylisse Bess, a chaplain at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center of Boston, believes the pandemic-induced interruption of mourning rituals has complicated survivors’ access to familiar forms of grief, while their age, identities, and class further determine their capacity for catharsis.

Within a racist medical system, and given astronomically higher Covid-19 death rates for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, many grieving people of color may question whether their loved one’s death was preventable, Bess said. She noted that people of color face systemic barriers to mental healthcare, and that employer-provided white therapists may dismiss the loss of chosen family or the rupture of kinship networks unfamiliar to them. To Bess, who is Black, grief work is justice work.

The algorithmic racism of life insurance can further upend the grieving process, says LaShaya Howie, who studies Black funeral homes. Racial capitalism means life insurance access mirrors more than income; policy rates vary by ZIP code, transmuting redlining into ostensibly neutral variables. While FEMA offers financial assistance for the funerals of people who have died from Covid-19, funerary expenses and attendant debts can aggrieve survivors by turning a funeral into a financial crisis. This pattern has spawned a tedious post-mortem ritual now all too common: GoFundMe campaigns for funerals, which, Kneese argues, allows “disparately located family and friends, as well as acquaintances or Internet strangers, to contribute to a person’s memorial fund, facilitating widespread, public participation.” The creators of these campaigns also leverage “practical knowledge of social media practices and other forms of online or marketing savvy” to convert digital compassion into sufficient funds. The latter imperative can shape imagined communities, connecting the deceased to similar victims—who died due to the pandemic, police violence, or environmental racism—as well as linking benefactors to one another, thereby channeling mourning into a movement.

(Image source: Matt Rourke for the Associated Press)

Experiences of grief care also vary by age. Most services are designed for older adults and young children as the primary mourners, with few tailored to those in between. Even in non-pandemic contexts, since few of their same-age peers have experienced the death of an immediate family member, adults in their twenties and thirties confront a distinctly isolated grieving process. Rising rates of depression, the fastest-growing health condition among millennials, further compound mental health issues within this age demographic, as do spiking healthcare costs, relatively low rates of insurance coverage, and stagnant wages.

With an especial lack of resources and outlets for processing grief, young adults are at risk of suffering long-term psychological and psychiatric effects, including depression, paranoia, and suicidal ideation. “It’s a lonely place to be: to have no one who’s able to just sit with you,” Bess said.

***

Few could sit with Rachel as she grieved. She faced pixelated, disconnected heads on a screen during Sauveur’s funeral, exacerbating a grief process that was already lacking in touch and tradition.

Compounded by the isolation and sedentary nature of a stay-at-home order, Rachel felt confined, locked into the same space where she first heard of her father’s death. Reflecting on the Christian hymn “It Is Well with My Soul,” she thought, “Well, it’s not well with me.” She spent several Sundays in a fetal position, reminded of losing her father on Easter Sunday. She described her distress like clockwork or a switch: Midnight would strike, and she could no longer leave her bed.

In May 2020 Rachel described her paralyzing grief to a close friend, who referred her to the Covid Grief Network. The Network’s first members, like Rachel, joined through word of mouth. They received six hour-long, one-on-one sessions with a volunteer grief worker over Zoom, and gained access to the Network’s Facebook group, through which they could share experiences and process their grief. To date, it has served 650 young adults from 44 states and 22 countries.

The Network’s co-founders—Noah Cochran, a clinical social worker, Ari Eisen, a non-profit manager, and Chloe Zelkha, a rabbinical student—offered in-person grief retreats in the Bay Area before the pandemic and realized days into lockdown that their former work would be on hold indefinitely. Many young people were about to move through grief in ways both familiar and wildly divergent from their own travails: Cochran and Zelkha both experienced the loss of parents when they were younger and encountered age-related gaps in grief care. With places of worship closed and hospitals overwhelmed, they sought to provide a place where others “joining the club” could commune and sit with their grief.

“My Judaism taught me the power of ritual,” Zelkha said. In grieving her father, she found solace in what she dubbed the “spiritual technologies” of her religion: the rhythms of sitting shiva, immersing in the mikvah, and saying the Mourner’s Kaddish, which offered “a road map” to express pain in grief, and to do so “without apology.” While all three co-founders are Jewish, they are careful to note that the Network is not a Jewish organization and is open to all.

(Image source: Covid Grief Network)

The first months of the pandemic involved mourning loved ones, daily life as we once knew it, and forms of grieving previously familiar to the living, said Cochran, who works as a therapist at Smith College. “People’s religious and spiritual practices, communities and lineages, traditions and rituals have been inaccessible or changed,” they said. With that shared understanding, the Network’s volunteers, who come from diverse religious backgrounds, often foreground the healing place of ritual in the grieving process. And, recognizing mental health care’s long history of racism, homophobia, sexism, and transphobia, the Network’s organizers connect members to volunteers who share their identities upon request.

Ylisse Bess, the Boston-based chaplain, volunteered for the Covid Grief Network and conducted one-on-one sessions with grieving people of color. She started each session with ritual: Deep breathing demarcated the beginning of their hour together, which was the grieving person’s to steer. In their first session, Bess would ask each person about their loved one: what their name was and who they were. She found that her grieving peers had acutely pent-up emotions; they negotiated mounting pressure to compartmentalize and, without irony, “live their lives” once the rest of the world reopened. The recognition of Covid-related deaths, and subsequent mourning, waned as conspiracies and vaccine determinism grew.

Bess believes the Network has been successful because it does not try to fix mourners’ grief. Such spiritual care diverged from her accustomed site of concern: the hospital. She witnessed a different life cycle to grief, meeting someone weeks or months into their processing, unlike her regular witness to grief’s genesis after a diagnosis or death.

“The Network has been an experiment in how to extend chaplaincy beyond the walls of the hospital, the military, the university, or the prison, where it usually lives,” said Zelkha. “We also decided to bring in a wide range of caregivers: not just chaplains or spiritual caregivers, but also therapists and coaches and beyond, so it’s also an experiment in expanding what chaplaincy is.”

Grieving people can largely choose from two options: clinical therapeutic help or nothing, argues Dr. Hannah Zeavin, author of The Distance Cure: A History of Teletherapy. Hybridized and adjunctive techniques like the Network’s fulfill a crucial niche. Its blend of pastoral care, mutual aid, and social work render it a religious and mediated cousin to the crisis hotline.

Bernard Duncan Mayes, who identified as a “queer Anglican priest,” founded San Francisco Suicide Prevention in 1961, the second hotline in the U.S. He looked to Samaritans, the world’s first crisis hotline, founded in 1953 by a British Anglican vicar, for inspiration, but Mayes consciously obfuscated his church affiliation so as to avoid excluding potential careseekers. The hotline sought to serve two marginalized groups: people struggling with suicidal thoughts as well as lesbian and gay people. Borrowing methodologies from both pastoral care and psychotherapy, Mayes derided churches and licensed psychiatrists alike for their forms of proselytizing—of the soul or wallet, respectively—as well as their pathologization of people in need through doctrine and diagnostic manuals.

The Covid Grief Network does not label itself as teletherapy, but the pandemic has shifted how mediated care work is approached, in part due to an exodus of in-person therapeutic care toward digital fora. “Teletherapy has been making its eventual grand debut for over 100 years now,” Zeavin said, framing Freud’s treatments by mail as the medium’s root.

***

In her Zoom-based sessions with a volunteer, Rachel Joseph started to approach her father’s loss and her own recovery from new angles. She learned to lean into healthy coping mechanisms: running, journaling, talking through her feelings with her fiancé Armando. She now treats Sundays as a day to remember Sauveur, though her grief isn’t complete or gone.

“He’s still with me in the spiritual sense, where even though his body isn’t here, I can still remember him,” she said. “He’s still in my heart, and he walks with me every day.”

She’s also invented rituals of remembrance. Her father used to drive the Joseph family around to look at Christmas lights; Rachel and her mother retraced those routes in December. Sauveur enjoyed Sunday meals at a Chinese buffet. Rachel and Armando revived that tradition, too, recalling his favorite dishes and classic Sunday outfit (a tie patterned with an American flag and eagle, and always the same hat). She found solace in going back to the times and places they shared.

The biggest milestone came when Rachel and Armando married without her father there. Armando had surprised her with a proposal in February 2020. The Joseph family—Rachel’s parents, two sisters, and brother—celebrated with the newly engaged couple over a loud, festive lunch. Armando notified Rachel’s notoriously loose-lipped relatives of the plan in advance. “They managed to keep it hush-hush,” she joked.

Sauveur remained a centerpiece of their wedding in August 2021. Armando assembled a remembrance table, which featured portraits of Rachel’s father, her brother, who passed away in 2011, as well as deceased grandparents from both Rachel’s and Armando’s sides of the family. Instead of the traditional father-daughter dance, Rachel danced with her surviving brother and cradled a framed picture of Sauveur.

And finally, with a slide show of family memories in the background, Rachel’s younger sister Anne performed “Peace,” an original song that had been part of her own grieving process.

“It is well with my soul,” she sang.

***

As the coronavirus mutates, defeating immunities and techno-fixes alike, leaving more dead and forcing countless others to say their goodbyes through a device and navigate a dissonant public, so too has the Covid Grief Network been reconfigured. In response to feedback from its members and volunteers, it has stopped offering one-on-one support and instead meets through 12-person cohorts.

The U.S. collectively lives (and dies) in what Hannah Zeavin, the teletherapy scholar, dubs a “state of suspended disbelief about death.” Many who survived pandemic-related deaths have seen public spaces, social networks, and economies drive themselves brutally toward “normalcy.” In the turmoil of wanting to sit with grief while the world “moves on,” and with most religious spaces reopened in some form, the Network’s organizers have found young adults most in need of solidarity and long-term community.

“I hope our world continues to move towards more community and collective holding of grief,” said Noah Cochran.

The Covid Grief Network continues to welcome new members and new rituals. In December 2021, Ylisse Bess, the chaplain, facilitated a group session over Zoom to mark Hanukkah. For many, this was their first winter holiday season without a loved one. Though many attendees came from backgrounds that varied from her own, Bess said that successful interreligious support involves showing up and letting others draw from their truths, including thousands-year-old traditions that connect individuals to their ancestors. “If that could get them through the Hebrew Bible, then maybe that can get them through 2021,” she said.

The Network looks to get through 2022 and other turmoil without losing sight of its main focus. “We orient towards Covid grief and loss in young adults in particular because we wanted to offer something particular and unique in this moment,” Cochran said. “We can’t do it all but we wanted to do one specific thing well, and that’s why we chose this particular niche.” It will live as long as it’s needed.

Adam Willems (@functionaladam) is a Seattle-based researcher and reporter. They write Divine Innovation, a newsletter on religion and technology.