Greg Bourke, Gay Catholic Activist, on Why It’s More Important to Stay and Fight

“If everybody just walks away, then the bullies are gonna win, the injustice is gonna remain, and nothing’s gonna get changed.”

(Image source: University of Notre Dame)

Greg Bourke claims he is just a “suburban dad, with a husband, two kids and a car.” But that’s his humble, soft-spoken Southern way of downplaying that he was involved in several important developments in the arc of 21st Century gay history. First, he took on the Boy Scouts of America and their policies after he was dismissed as a troop leader in 2012 for being openly gay. Then he was one of the plaintiffs in Obergefell v. Hodges, arguably one of the most important Supreme Court cases of our lifetime, since it radically changed the idea of marriage in the United States.

“I didn’t expect to be any kind of an activist. All I wanted to do was live my life quietly here in Louisville,” he explains. “But when you have a family, life gets complicated. Then you also realize you have an obligation to your children, and to the next generation.”

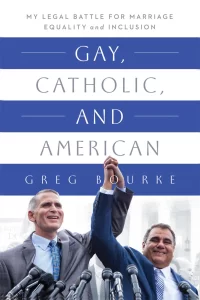

In his 2021 memoir, Gay, Catholic, and American, Bourke gives a heartfelt account of what it took to grow up in working-class Kentucky and what propelled him to fight for marriage equality and LGBTQ inclusion. Yet, despite being a trailblazer who has helped shape policy, he maintains that his domestic achievements are the ones that truly matter.

“Trying to raise a family as a gay couple in the Catholic Church was probably one of the hardest things that we did. The Supreme Court case played itself out over a little more than two years. But when you have a family, it’s a lifetime commitment.”

As the United States approaches the 10-year anniversary of the Obergefell decision in June—and with many anxious that it could be overturned—Greg Bourke spoke with us about the current state of LGBTQ equality, the battles that remain to be fought, and his hopes for the future.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Jerry Portwood: Your book is obviously an important historical archive. What compelled you to write it?

Greg Bourke: I had a bit of an awakening, or a calling, that occurred while I was at church. It just kind of compelled me to take a look at what had been going on and transpiring in my life and to really reflect, analyze, and then record it. Because I think that a lot of that wouldn’t have been available to people. A lot of that history has just been lost.

Another thing that I think is important is, you know, my husband Michael and I, when we got together in 1982 in Kentucky, the world was a very different place; the odds were very much stacked against us. I think it’s important to capture for people what the world was like when we made that commitment to each other and how remarkable it is that we’re still together today in 2025. We were the exception.

JP: Plus, your book details how many logistics go into doing advocacy or activism.

GB: Absolutely. I really don’t think people appreciate that. We didn’t have a lot of downtime during those years. If you have a family, where both parents are working full-time corporate jobs that are very demanding, and you’ve got children in high school, and you’re trying to help ’em, support ’em, and get ‘em moving in the right direction, it takes a tremendous amount of time to just keep up with those things. So, if you add on trying to take on the Boy Scouts of America and then take on the federal court system—it was pretty overwhelming at times. But we lived to tell the tale and, through all that, Michael and I are still together as a couple, and I think we’re probably happier now than we ever have been in our lives.

JP: People don’t always remember that you were among many other plaintiffs in Obergefell v. Hodges because Jim Obergefell was the named plaintiff. Can you explain how that happened and what it’s like for his name being the one front and center?

GB: Obergefell v .Hodges filed first. [Our lawyers] filed six minutes later. So, if a couple things went different ways, that case could have been named Bourke v. Beshear. I’ll tell you what I’ve told Jim Obergefell many times: I was glad that it was his name on the case instead of mine.

I’m sure there are a lot of great advantages and perks to it, but I’m glad it was him instead of me. And I still feel that way. From my perspective, it’s been difficult at times. Michael and I have had to endure a lot of pushback, a lot of criticism. So I’m really grateful that it was not my name on that case.

JP: I know it can be quite difficult being Catholic in some parts of the South. How was it in Kentucky? Did you ever feel othered?

GB: Speaking about Catholicism in general, I am an Irish American. My great-grandfather came from Ireland, so I grew up in this big Irish Catholic family. Every weekend, we would go and have dinner at my grandparents’ houses, hang out with my cousins. Every weekend we had a family reunion! Everybody was Catholic. And I went to Catholic school, right? So my whole world revolved around this Catholic community in Louisville. So let me talk about Louisville: we have more Catholics than we do Baptists or Presbyterians, so there’s a huge population of Catholics here.

GB: Speaking about Catholicism in general, I am an Irish American. My great-grandfather came from Ireland, so I grew up in this big Irish Catholic family. Every weekend, we would go and have dinner at my grandparents’ houses, hang out with my cousins. Every weekend we had a family reunion! Everybody was Catholic. And I went to Catholic school, right? So my whole world revolved around this Catholic community in Louisville. So let me talk about Louisville: we have more Catholics than we do Baptists or Presbyterians, so there’s a huge population of Catholics here.

So that was the world that I grew up in, and I really didn’t feel othered; I kind of felt more like I was in the majority. In that respect, I was comfortable and happy with that—just because I got so much good reinforcement from my family, from my friends, who I am still in contact with.

JP: You’re highly active in your church; you’re highly active in the Boy Scouts of America; then you’re highly active in all these legal cases. Yet, your mission was to have a family before you took on these powerful institutions. What kept you going through all of this? Because it seemed like a ton of work!

GB: I think a lot of that drive comes from my background and my family. My siblings—I have three brothers—they’ve all been extremely successful in their lives. We came from a family where that was kind of expected. We grew up in a Catholic community that expected you to excel. We went to very challenging schools that compelled us to not only achieve academically but also to be of service to our fellow men, to be faithful stewards as best we can.

My faith has driven so much of what I have done in life. The fact that I wanted to get involved in sustaining a relationship over a long period of time—like my parents who were married for 67 years when my father passed—I wanted to have that relationship. I wanted to have a family at some point. I don’t think either of those things are outrageous asks. There are so many millions of Americans who seek and achieve the same thing.

Now, as an openly gay man—I’ve been out since I was 19 years old, and I’m 67 now—I never really had to deal with discrimination. Nothing that I couldn’t handle, nothing that really motivated me to get extremely active until I got ousted from my position in the Boy Scouts as a Scoutmaster. When they said I was not competent to do a job that I’d been doing for 10 years, that was the last straw. Prior to that, I was just so fortunate in terms of being able to be openly gay at my place of work; I never got turned away from a school, or a job, or any kind of a social group because I was openly gay. It was only when the Boy Scouts said, “You have to leave,” that I knew how wrong that was. I knew that was happening with other people, but it wasn’t happening to me.

I think it’s what many people have to experience: you have to have that personal experience of discrimination to really get motivated. Now, I appreciate all the people—and there are plenty of folks—who get out there and get active just because it’s the right thing to do. But for the first big majority of my life, you know, what was important to me was having a job, having a relationship, having a family. And that was a lot to do as a gay man. So I didn’t really feel like I had a whole lot left to give until something happened to me. Then some opportunities presented themselves to me, and I acted on it.

JP: I think many people would be angry. Instead, you said, “I love the Boy Scouts and I wanna change it.” The same with the Catholic Church. You don’t exhibit that sort of animus. Instead, you decided: I love this thing, and I’m going to make it better.

GB: Well, I wish more people would do that. Yes, you’re right. Sometimes the easier thing to do is just to pack your bags, shake the dust off your feet, and walk away and say, “I’m not welcome here; I’m leaving.” I never really felt that. I’ve never had a break with the Catholic Church. I’ve never had that moment where I said, “I can’t go back, or they don’t want me to come back.” So I’ve been able to sustain that over a period of my whole lifetime. And it’s so important that I had that continuity in my life to be able to just have it going and going and going. I get frustrated with the church but never to the point where I get really angry or want to leave.

To get back to your question, I think it’s harder to stay and try to fight things and make things better. But as I have seen personally, if you stay, then people have to continue to deal with you. You know, then the opposition is gone.

As my husband says all the time, “If we leave, they win.” If everybody just walks away, then the bullies are gonna win, the injustice is gonna remain, and nothing’s gonna get changed. But if you stay, and you’re reasonable and you explain why you should be included, why this shouldn’t have happened, why it should change, you know, people kinda have to listen to you. I mean, they can tune you out to a certain extent, but if you get enough people together—and you’re putting the messages out there in the right way—they have to acknowledge that and deal with it.

JP: Right now, issues around masculinity are swirling, and you’ve been involved in organizations that deal with a version of masculinity. When JD Vance says something like, “We’re gonna get the normal gay guy’s vote” or the “acceptable gay,” what’s your reaction to that?

GB: I don’t know what he’d consider a “normal gay” anyway. Because I don’t know who he knows or who he doesn’t know. But I just thought that was out of line. I don’t think there’s a thing as “normal gays”—there’s just gays! I mean, we’re a broad range; there’s a spectrum. You’ve got the boring ones—like Michael and me—who are perfectly satisfied to wrap our lives together and live ’em for 43 years and just deal with whatever comes up. Then, you have other people who have a variety of different lifestyles and attitudes and things that they are seeking out of life, and I respect them all.

JP: What about Pope Francis? By the time this piece publishes, we don’t know if he’ll be with us since he has serious health issues. But I wonder what you think about his legacy. At one point, he appeared inclusive toward LGBTQ people—now gay people can be baptized and can be a godparent—then he said other negative comments about “gender ideology” and trans people. How has all of that affected you?

GB: I’m coming from that progressive wing of the Catholic Church, and I’m confused by it. I think people on the more conservative side of the Catholic Church are just as confused, just as frustrated. So I have some sympathy for them. We’re all in the same place. He has not had a consistent message; he’s reversed course a couple of times; he’s been caught using gay slurs. It’s frustrating, and I think the whole church would like more clarity.

We recently, at the Pope’s direction, went through this Synod project for a couple years where we listened to people at a very grassroots level, and it was all supposed to flow up. There was optimism that there would be some great changes that came out of that, whether it was going to be women deacons or better inclusion of LGBTQ people. And practically none of it happened.

That’s what’s frustrating to me: that we have a Pope who is so often criticized for being “too progressive,” and too “soft on gays,” and all this, and from my perspective, things haven’t really changed that much. I don’t know what people are complaining about; church doctrine has not changed.

So yeah, I get frustrated with the Catholic Church, but I also know it’s my home. And I don’t know who I would be without my experience in the church. It’s been so integral to my whole life—from baptism to right now. I’ve always been active in the church.

It’s the same way I can’t envision not being an American. I know people who expatriate and retire and move to other places. But I can’t imagine not being an American. It’s still my church, the same way that this is still my country—with all its flaws.

I don’t like what’s going on with the country, but I’m not gonna disown my country, and I’m not gonna disown my church. They’re just too important to me, so I will take those to the grave with me and do it gladly.

JP: Speaking of, in your book you describe a recent battle to get your joint tombstones into a Catholic cemetery. That was shocking!

GB: I didn’t realize we were gonna get that much pushback. Michael and I were planning to do this anyway—we wanna get buried in the Catholic cemetery. We didn’t realize this was gonna turn into, like, a nine-month process of getting the archdiocese to approve our tombstone. It was frustrating; it was everything.

I got a little angry over that, but it was a situation where it was good news, bad news. We kind of took the archdiocese on, and they said, “OK, we’re not gonna give you everything you want. We’re gonna allow you two to be buried together, in a Catholic cemetery, so we’ll allow you to have a joint headstone. But, we will not allow you to have certain elements on that headstone.”

This was a very public battle. We had the local media covering this, and the archdiocese was forced to make a decision, and it set a precedent: Yes, two same-sex people can be buried together, in a grave like this, we just can’t have the interlocking rings. So, you know, we got most of what we wanted, and we think it was an important fight that we took on.

JP: How do you feel that, since your case, the Supreme Court has gotten more Catholic and more conservative?

GB: It doesn’t bother me that it’s so Catholic, but it does bother me that it’s so conservative Catholic. The three that were appointed by President Trump really shifted the nature of the court. They were brought in, in my opinion, specifically to target Roe v. Wade and, in fact, they did. I’m not sure what will happen beyond that. I think it’s possible that they could pivot and target Obergefell. It hasn’t happened yet, but it could.

For years, people would come to me and ask, “Are you concerned with what they might do with Obergefell? Are you concerned with what they might do with Roe v. Wade?” My response was always: “That is settled. I’m not worried about it. Listen to what they said in their testimony when they were being vetted in the Senate. That’s finished law, and we’re not gonna revisit that. They don’t overturn stuff like that!”

Then what happened?

So now I have an ultra-cautious approach, and I feel like it could happen; it might happen. Yes, we have the Respect for Marriage Act, and I think that’s great. We were there when it was signed, and I thought that was fabulous! I think it’s a very good protection. But I think what a lot of Americans are starting to feel is that anything that’s been done in the past can get undone very, very quickly these days—if people don’t stand up and fight for it and try to stop it from happening.

You know, I’m willing to do my part, but there’s going to have to be a whole lot of other people who stand up, too.

JP: I appreciated that you wrote about how you got very frustrated with people saying, “We have to wait until you change hearts and minds before we can get this form of equality.” It reminded me that this is a euphemism for how the minority must try to change the ideas of the majority, which in fact is why we have democracy. Because the majority isn’t supposed to crush the minority, and it isn’t actually the minority’s job to change hearts and minds—it’s the job of a representational democracy to protect everyone. Right?

GB: I felt like we had been waiting long enough. If it was simple, it would have happened more rapidly than it did. At a certain point, you realize some people’s hearts are so rotten, you can’t change ’em, and their minds are so bad, they’re unwilling to listen to arguments for reason or to think empathetically. It’s a small number of people who are willing to dig in and do whatever they can or whatever they have to keep from having to change or think about change.

JP: Well, change is scary.

GB: Right, the change part is what people are resistant to; some people don’t want to change. They learned something when they were very young, and it’s really hard to change the way they think, the way they feel, and what they believe when they learned it so early in life. They got it time and time again, and it’s been reinforced for so long.

Our only hope is the next generation that comes up after is gonna be a little more open. I think that’s proving to be the case.

Jerry Portwood is the founder of The Queer Love Project and was a top editor at Rolling Stone, Out magazine, and New York Press. He’s a long-time instructor at the New School, where he teaches essay writing and arts criticism.