From Scrolling to The Scroll: A Model for Learning about Crises that Demand Our Attention

Slow learning, based on Jewish textual study and open to everyone, to counter hot-takes and better understand today’s world

(Image source: CC Adobe)

The current situation in Israel and Palestine is profoundly complicated. And yet, countless people and pundits portray the solution as a simple one. As someone who has been invested in the region for decades, the one thing I know is that if someone says something is simple, whatever comes next is likely to be wrong. I am so frustrated by faulty analogies and pieties proclaimed with astonishing and unearned confidence.

We can agree (I hope) on a few basic truths: human life is sacred. Torture is unacceptable. We want the violence to end safely and as quickly as possible. That is the starting point. I suggest we take time to consider what we say next.

Part of the problem is that when it comes to being updated on world events, too many of us feel like we don’t have time to take. That’s a specific statement about the current set of global crises, and a general one about how we come to know things. We can always access the latest news, and we feel that, as engaged citizens and responsible people, we ought to do our best to stay abreast. We scroll, sometimes desperately, sometimes mindlessly. We think we know something. And we move on.

Scrolling has become the 21st century way of knowing. Or, in reality, the illusion of knowing. There are many different ways to scroll. We scroll through social media feeds, consuming news, entertainment, and advertisements indistinguishably, and maybe thoughtlessly. It’s a verb: to scroll.

But it is also a noun and a textual medium: the scroll.

In an age of corporate media insta-expertise and social media hot-take influencers, using “the scroll” as a text encompasses an entirely different way of consuming information: a process of ending only to always, and by design, begin again.

At this time of unimaginable tragedy and widespread war, famine, and needless death, I offer as an antidote to screen-scrolling this much older model of the scroll. I offer the benefits of cyclicality and repetition as a technology for taking time. I offer, based on my experiences working with Jewish texts and sacred scrolls, slow learning as a way to counter the shallow, sometimes incorrect, and often dangerous assumptions of knowledge about the incredibly complicated conflict in the Middle East that has migrated from the online sphere to everyday life. I personally feel differently about the conflict than I did in those terrible, heartbreaking days after October 7th. My heart is still broken. It is all still terrible, even more so. But many things have changed.

For millennia, Jewish communities have turned to a rich corpus of texts for legal guidance, ritual practice, community-building, and moral clarity. For some, the texts themselves are sacred, a direct connection to the word of God. For others, the process of studying the texts itself is sacred, a connection to Jews of the past, present, and future. Some find only pain in these patriarchal writings, feeling isolated and abandoned by a religion that is built around these historical documents. Some find solace and wisdom in the flexibility of Jewish texts, building upon them to create and excavate new communal meanings.

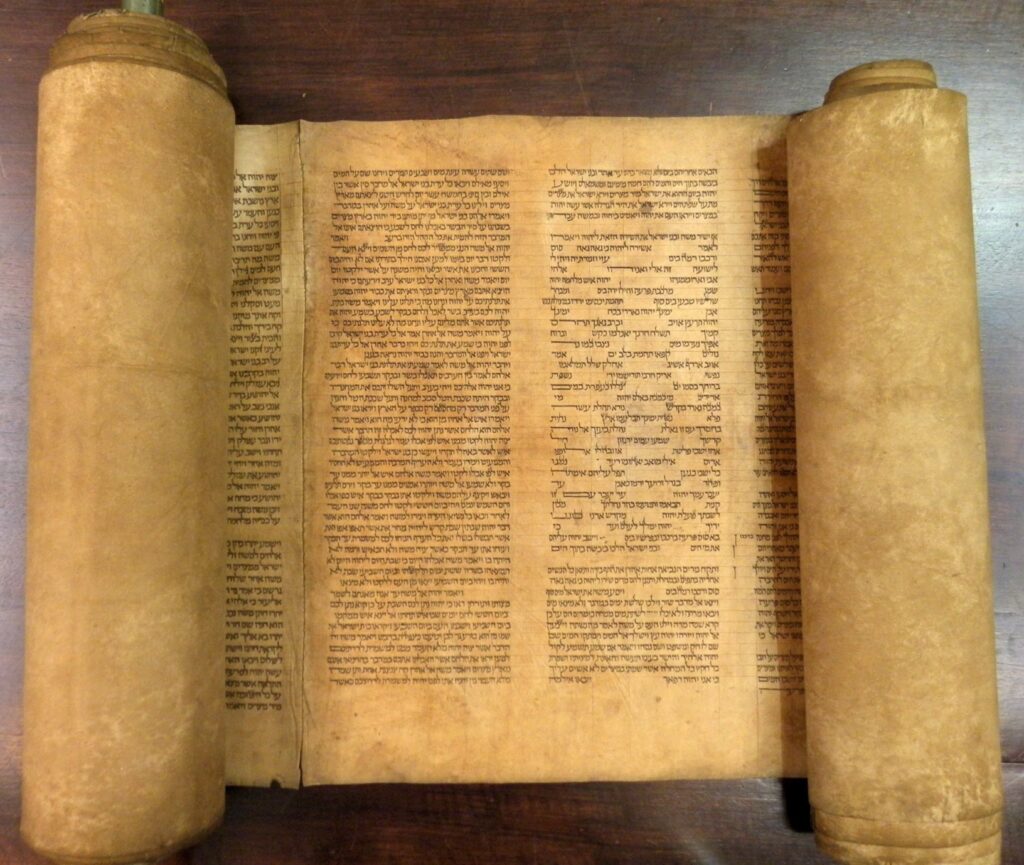

Listening, pausing, reflecting, repeating: these are structural ways to deepen our relationship to texts, to knowledge, to ideas. And they are built directly into the Jewish calendar, starting with the Saturday synagogue service. Each week, Jews gather in sacred space to pray together, chanting and singing the liturgy and listening to the cantillation of the weekly Torah portion. This happens on a yearly cycle, in which a chapter of the scroll, comprised of the five books of Moses, is sequentially chanted aloud each week. The ba’al koreh, or designated reader (or readers), stands in front of the scroll that is placed on a special table amid the congregation and, publicly and clearly, recites a portion of the Torah to a community that, if they were there for that section the prior year, has heard it all before.

(Torah scroll. Image source: National Geographic)

It’s a deeply sensual process: before the reading begins, someone carries the Torah, covered in fine dressings, through the congregation where people touch it, symbolically bringing the text’s teachings into their lives. Then there is another sensory experience: the sound and sight of the scroll being opened and rolled as the reading progresses, starting with the bulk on one side until, by the end of the Jewish year, it has shifted entirely to the other. Only, at that point, to be “refreshed” as it is manually rolled to the start to begin again.

The Torah is one kind of scroll, read weekly; there are 5 other scroll texts, or “megillot” we read once a year at set times of the Jewish calendar. We read them again the following year. And the year after that. The words don’t change, though our relationship to them does as over time as we – and the world around us – change. These are communal reading practices, designed not only to build relationships to texts but to build relationships with each other.

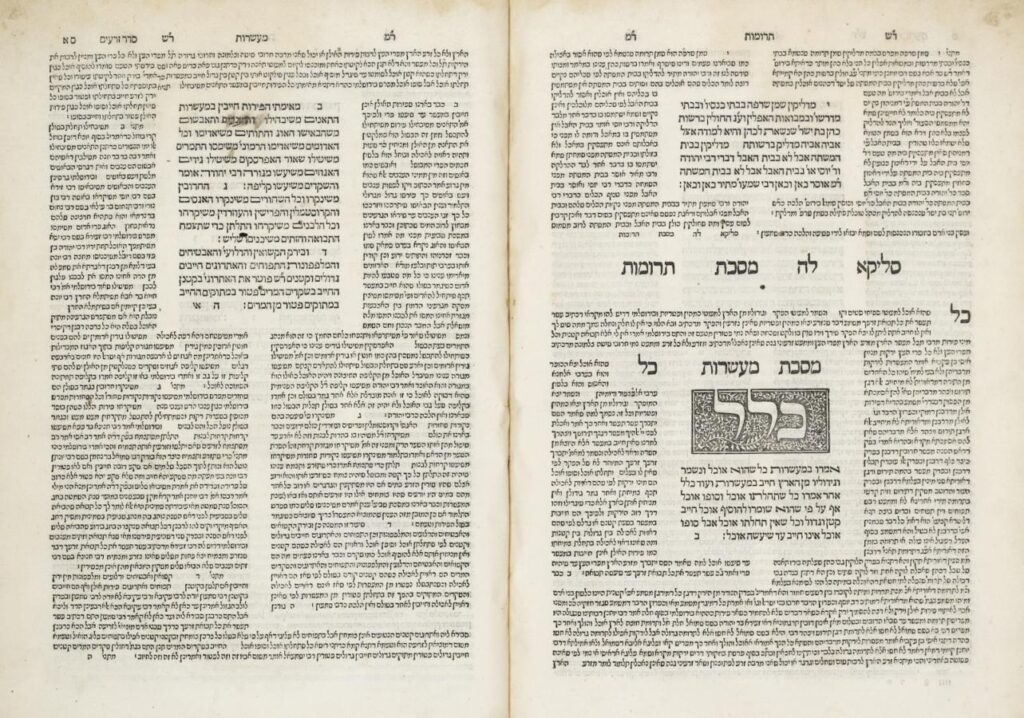

The Jewish tradition contains additional models of slow learning that are useful today, including the practice of Daf Yomi, the daily page of Talmud study done by Jews around the globe in continual synchronized cycles every 7.5 (!) years. The Talmud is a written collection of Jewish law and tradition dating from the fifth century CE that serves as the foundation of Jewish practices and ethics for daily and communal living. It’s a process that may seem simply unfathomable in our content-obsessed culture.

Founded in the early 20th century as a way to connect diasporic people in a project of communal learning, Daf Yomi has extended across denominational and observance divides. There are multiple ways of “doing the Daf,” from group shiurim (traditional Jewish learning classes) to chevruta (learning partnerships) to podcasts to blogs to just opening the book (or screen – there’s an app for that!) and reading. If you regularly ride the Brooklyn subway, there’s a good chance you are familiar with the sight of someone hunched over a page of Talmud studying the day’s daf. People do it at different times of the day and via multiple media, but all participants are literally on the same page across the world for 7.5 years. At the end of the cycle, various communities throw a big party. And the next day, if they choose to keep going, they start back again on page 1. For another 7.5 years. It never ends. It’s not supposed to.

(Pages of Talmud. Image source: Jewish Learning Today)

Daf Yomi has a lesson for all of us. No matter how many times you read something, no matter how often you review the same set of words, and no matter how close to mastery you have achieved in a set of ideas, there is still more to learn. There is always more to learn. It’s a deeply humbling approach to knowledge and expertise. In contrast to the Google-on-demand environment, where new information updates every second, these ancient texts serve as the beginning rather than the end of how we know. Even still, the Daf is amongst the shallower types of textual encounters within the Jewish tradition; a page a day doesn’t allow the space to truly cultivate the deep, slow approach to ideas that characterizes intensive Jewish learning found in yeshivot, or seminaries devoted to full-time Jewish textual studies. But that’s not the point of the Daf. Instead of textual mastery, the process cultivates a habit of mind and practice: learning is daily, dynamic, and goes the distance. And, again: it’s repeated, over and over and over. There is always something new to learn.

Our access today to on-demand information, accurate or otherwise, has changed not just what but how we read, and how we come to know things, and how we make ethical, emotional, and practical decisions about what it is we believe we know. As someone who teaches ethics, I worry about the ramifications of this approach to making judgments about complicated issues. Our responses ought to emerge from thoughtful consideration and, if not personal expertise, then assessments based on trusted interlocutors, leaders, and thinkers. But the world and its crises move so fast, it seems challenging to develop any kind of depth of knowledge. It’s not just tempting to opt for the screen scroll, and it’s not that we’ve almost forgotten there are other ways to know; it’s that we think they are worse. What’s the point of repetition and depth when, in the blink of an eye, everything has changed? But most of the urgent things about which we need to know: war, famine, structural oppression, violence, poverty, and disease are a long time in the making. And that’s exactly the point of the cyclical scroll: we return to stable texts, repeating words precisely as a way to reflect on all that has, in the intervening time, changed. We learn new things from that which is the same.

I want to pause on the term “taking time.” It’s one of those phrases that has become so common that we don’t consider the language itself, which implies a process, an action, even a transaction: something is actively taken. We take time to: make sense; do work; rest; and we take time for: a project; a process; ourselves. It is both a demand and a gift. And it can – and perhaps uniquely at this moment ought to be – a scared duty. In the era of content consumption and scrolling through headlines and hot-takes, when it comes to how we know, we have stopped taking time.

Social media is one way to know things, and has its advantages alongside myriad and ever-increasing problems. One of these problems is that, for so many people, it is the only imaginable way to know about the world, especially in times of crisis. And I get it: there is so much out there, and things move so quickly, and most of us just want to be responsible citizens on the right side of history. Social media can be the quickest way to access information on the ground, sometimes showing us images and events we wouldn’t otherwise see. It can bypass gatekeepers, challenge censorship, and give access to non-traditional voices and makers. If we want to stay on top of emergent situations and be able to form opinions and exchange ideas, we start scrolling. It makes sense and it can be a double-edged sword: gatekeepers ideally serve to verify and vet information, place events in context, and offer depth and expertise. But of course, sometimes they fail. How do we balance direct access to, say, the voices of the minoritized, oppressed, and persecuted with a growing (and necessary!) distrust of what we see online?

I suggest, we pause. We use the model of cyclical learning to reframe our relationship to on-demand information. We look at our screens and we sit with what we see. We take time to reflect, using social media as the beginning rather than the end of the learning process. Instead of scrolling on our screens, we reimagine our screens as scrolls, with texts that serve as the basis of investigation, learning, and understanding. Instead of virtually forwarding and sharing at the click of a button, we discuss – in real-time, and real space – what we’ve read and what we imagine we know. We return, revisit, repeat. It works. I know that in those heartrending days after October 7th, everything I read was filtered through grief, horror, and fear. I still grieve; I’m still horrified; I am still afraid. But with time, with intervening events, I can know things differently. The moral clarity of David Myers’ plea for empathy has compounded over time; the gaping hole left by Mehdi Hasan’s show’s cancellation, following Hasan’s criticisms of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, grows ever-wider.

Instead of scrolling past Palestinian writer Heba Abu Nada’s final Facebook post from 8 October, we can revisit her words: “Gaza’s night is dark apart from the glow of rockets, quiet apart from the sound of the bombs, terrifying apart from the comfort of prayer, black apart from the light of the martyrs. Good night, Gaza.” And we can sit with the 2018 words of murdered peace activist Vivian Silver, who asked the Israeli government to “Show the required courage that will bring changes of policy that will bring us quiet and security,” even as she insisted “terror does not make anything better for anyone.” Let these words be our texts. Let us study them, learn from them, and live with them. Let them form our scrolls rather than scroll past them forever.

Alongside the fast, let us embrace the slow. The infinite scroll of the screen with its disappearing feed may be our current default, but we can turn to another infinite scroll as we remind ourselves that there are words that do come back. We can – and should – see knowledge as a process. We can – and should – reach for expertise that is not just wide but deep. We can embrace slow learning and repetition and communality and the taking of time, turning to texts that refresh by saying the same thing again and in so doing, allow us to learn something new. We can – and we should – insist on the sacred within the scroll.

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Medical Ethics and History at Drexel University. Her most recent book is Do I Know You? From Face Blindness to Super Recognition (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), and her book Mask is forthcoming in May 2024 with Bloomsbury Academic. She has written for The Washington Post, The Conversation, Real Life, Aeon, Tablet, Lilith, Kveller, and other places available on sharronapearl.com.