Forbidden Transactions Between Muslims and Hindus in Gujarat, India

A law that restricts Hindus from selling property to Muslims—and what that foretells about India’s future

(Image source/credit: Getty/Dreamstime/Indiamart)

When Onali Ezazuddin Dholkawala and his business partner Iqbal Tinwala tried to purchase a store in the Indian state of Gujarat, he did not anticipate a battle with local authorities that would last more than seven years. Dholkawala had entered a mutual agreement to purchase the shop from Dinesh and Deepak Modi, who are Hindu. But Dholkawala is Muslim. Buying property in Gujarat has never been easy for the state’s nearly 5.8 million Muslims because of long standing prejudice. But now, Muslims like Dholkawala face an even more difficult challenge with a law that restricts the purchase of properties between people of different religious communities.

Titled the “Gujarat Prohibition of Transfer of Immovable Property and Provision for Protection of Tenants from Eviction from Premises in Disturbed Areas Act,” the law is more popularly known as the “Disturbed Areas Act.” The law’s original intent was to prevent the distressed sale of property by those who were vulnerable to eviction after an episode of communal or interreligious violence. In the aftermath of riots in Gujarat in 1985, a growing number of people who were minorities in their neighborhoods started selling their properties so they could go live in neighborhoods where they would be part of a majority. One of the first of its kind in the country, this legislation came about to prevent segregation. But today, legislators use the law to promote segregation by creating a rigid divide between where Hindus and Muslims can purchase property, thereby ghettoizing the region’s Muslim minority.

Under this act, the district collector, a bureaucratic official in each county, has the power to decree a particular area as a “disturbed area,” usually if that neighborhood has had a history of communal violence. Once this classification is in place, people can only sell property to those outside of their religious community if they receive the collector’s approval. To do so, both the buyer and seller must file an application along with the seller’s affidavit stating that they sold the property of their own free will, and received a fair market price. The system leaves mixed-religion buyers and sellers at the mercy of a government official’s approval. And any violations of these stipulations lead to imprisonment and fines.

For people like Dholkawala, the ability to purchase property rests in the hands and whims of district collectors. In 2017, a deputy collector rejected Dholkawala’s purchase and ordered a police inquiry into the matter since the property was in a predominantly Hindu area. The collector ultimately rejected the application on the grounds that it was likely to “affect the balance in the majority Hindu/minority Muslim strength” and could develop into a “law and order problem.”

Not one to be deterred, Dholkawala took the matter to the courts, first appealing before the state’s special secretary of the revenue department (SSRD), and then the high court. In 2020, the Gujarat high court ruled in the favor of Dholkawala and his Muslim business partners. But they soon faced another set of hurdles from right-wing Hindu neighbors in the area adjacent to his shop.

“I bought the property in 2016, but it is only today in 2023 that I can finally use it,” Dholkawala told me during an interview for the Revealer. “The collector hadn’t given permission at first, saying that it would disturb the equilibrium of Hindus and Muslims in the area, that there would be an increase in Muslims in one neighborhood, and the number of Hindus might fall. Finally, we went to the high court, where the verdict was in our favor. But even after the court’s initial verdict, when we decided to work on repairs for this property, the locals of the neighborhood started threatening us, and we even filed a complaint with the police.”

Dholkawala adds, “We were told that Muslims have illegally acquired property amongst Hindus, even though the sellers had sold it to us of their own free volition. This law is such that even if the private parties relevant to a transaction agree, any random third party can complain despite having nothing to do with the sale!”

In February 2023, the high court imposed a fine on the Hindu locals who were harassing Dholkawala. But pervasive discrimination persists elsewhere in the state.

(Gujarat, India. Image source: Wikipedia Commons)

Since 1969, Gujarat has seen rising violence between Hindus and Muslims, culminating with the 2002 riots that disproportionately targeted Muslims across the state. Official estimates claim a death toll of nearly 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus, but unofficial figures from activists, lawyers, and others estimate over 2,000 deaths – Muslims being the most affected, despite accounting for less than 10% of the state’s total population.

Prior to the 2002 riots, however, relatively smaller-scale conflict also existed, including riots in Ahmedabad, the state capital, in 1985. “We do have a sense that Ahmedabad was not as segregated back then until the mid-1980s, when a continuous wave of riots took place, as much as it is now,” says Sharik Laliwala, a Ph.D. student and researcher at UC Berkeley. “I grew up in the older part of Ahmedabad hearing stories from my parents and grandparents about our Hindu neighbors and they still meet at festivals and weddings.”

But the wave of violence from 1985 onwards marked a key change. “Hindu neighbors shifted out to Hindu-dominated parts certainly by the mid-to-late 1980s, while more Muslims took up their residences as they moved from Hindu-dominated localities for safety reasons,” Laliwala noted.

It was during that wave of violence, in 1986, that the government put in place the Disturbed Areas Act to protect individuals from the distressed sale of properties. This law was re-enacted in 1991, in its misused and current form

***

In 2018, far-right Hindu organizations spread rumors throughout Gujarat’s capital city of a purported “Land Jihad.” After a Muslim real estate developer was set to redesign a building where both Hindus and Muslims lived (albeit separately), far-right groups stopped his project, accusing the builder of trying to drive out Hindus from the area and committing “Land Jihad.”

The coinage of “Land Jihad” refers to the Islamophobic theory that Muslims “capture” residential and public properties to bring them under religious control, and to increase the Muslim population of a locality.

Conspiracy and Islamophobic theories such as this have become increasingly popular throughout India as the Hindu nationalist consolidation increases under the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Since 2021, the BJP-led government in the country’s northern state of Uttarakhand has been tracking “illegal land deals,” citing concerns around the “demographic change” in population.

Such a political climate has facilitated the presence of far-right groups like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (literally “World Council of Hindus”) to descend into vigilantism against Muslims and other minorities. These groups have also launched campaigns against interfaith relationships, which they call “Love Jihad,” and have promoted the falsehood that Muslim men can make Hindu women fall in love with them so they can convert them. As recently as February 2023, far-right Hindu groups in India’s cosmopolitan city of Mumbai rallied against Muslims, with slogans against so-called “Land Jihad” and “Love Jihad.”

The country has also witnessed a sharp spike in incidents of mob-lynchings and hate crimes against Muslims, including a wave of hate speeches and calls for the economic boycott of Muslim-owned shops and businesses by political leaders from the ruling party. Despite the Indian Supreme Court’s sharp criticisms, television channels also launch frequent anti-Muslim primetime debates, accusing innocent Muslims of committing various acts of “Jihad,” from spitting in peoples’ foods to molesting women, and more.

Meanwhile, the Disturbed Areas Act has become even more radical. A 2020 amendment allowed collectors to reject applications for property sales if there is any “likelihood of polarization,” “disturbance in demographic equilibrium,” or even the “likelihood of improper clustering,” based on religious or other identities.

(Image source: Getty/Dreamstime/Indiamart)

Lawyer Muhammad Tahir Hakim challenged these amendments as unlawful and finally succeeded after the state’s high court put a stay on them.

Hakim told me, “If you see the earlier, original Act, it is a bona fide piece of legislation. There’s no malafide intention. It was framed because of communal riots in Gujarat from 1985 until the demolition of Babri mosque in 1992. It was so that people do not sell off their properties under duress. If they still needed to sell it off, this helped protect the legitimate market value of their properties. Unfortunately, the act has been distorted to create ghettoization.”

***

Despite Hakim’s few legal wins, most other people are afraid to file discrimination lawsuits and are compelled to make do with the status quo. In Rajkot city, in the southern-central part of Gujarat, Amir Petiwala (name changed on request) has been struggling to buy a house for three years. Petiwala is a Shia Bohra Muslim and made an agreement to purchase land in December 2020. But in January 2021, state authorities added 28 upper-middle class and upscale housing societies in Rajkot under the ambit of the Disturbed Areas Act. This included the place Petiwala was planning to purchase.

“I successfully made an agreement of land purchase with the seller who belonged to an upper-caste Hindu background in December 2020,” Petiwala said. “This area where I intend to buy a piece of land is not even a really posh city area, but more a middle-class area. Now, someone like me needs to take permission from the collector of the city before making the registration of the property. And contrary to the name, this area did not have any disturbance at all and everyone lived in harmony!”

Petiwala’s difficulties to purchase a home reflect a larger problem. He says that even though he could afford to move to a nicer area, “the [Hindu] neighbors can unite and complain against us to any competent authority, which makes it impossible to buy a residence to live with a family with kids.” He adds that, “there are hundreds of other Muslims and some Hindus as well who are struggling to sell their properties from these areas. Hundreds of applications are pending or rejected by local police verification or local bureaucrats or district revenue authorities without any reason.”

Hakim echoes this sentiment. Even though the recent amendments have been stalled, the Act still allows for district authorities to reject property purchases if anyone complains or objects to it – for any reason. “At the ground level, what happens is that people either succumb to such objections raised by neighbors or by any rightwing Hindu third parties who are not privy to the sale, or they try to grease the palms of the persons who object,” he said.

The law mandates that an area can be declared “disturbed” only in cases of continuous riots and violence. In reality, even without such riots or violence, authorities have arbitrarily marked areas as disturbed.

“Today, despite the 2002 communal pogrom [over three days of communal violence in Gujarat, which left over a 1,000 people – primarily Muslims – dead] under then Chief Minister Narendra Modi, people push the image that Gujarat is one of the most peaceful states,” another lawyer told me, speaking on condition of anonymity. “If it is so peaceful then why do they need this law, and in so many places? It’s completely dichotomous! On one hand you say there are no communal tensions or riots, and on the other you go expanding the number of areas held to be ‘disturbed’ by communal violence.”

According to new research by scholar Sheba Tejani, the designated “disturbed areas” in Gujarat’s capital city of Ahmedabad grew by 51% between the period of 2013 to December 2019, now covering nearly 8.4% of the city’s total area. Pointing to the heightened religious segregation, Tejani highlights how the law has allowed for entire villages (and the fields surrounding these villages) to be designated as “disturbed,” without authorities providing any clear justification.

***

Writer and Amnesty International campaigner Aakar Patel draws parallels between Jim Crow-era laws in the United States and the present-day housing segregation in Gujarat. He emphasizes that “When segregation in the United States was legally ended in the 1960s, the government passed laws that sought to integrate the races, like the Fair Housing Act. It prevented discrimination in the buying and selling of properties which was keeping the races separate. All across Gujarat, in all major cities and in several towns, the government has done the opposite. Muslims are deliberately forced into ghettos through a law.”

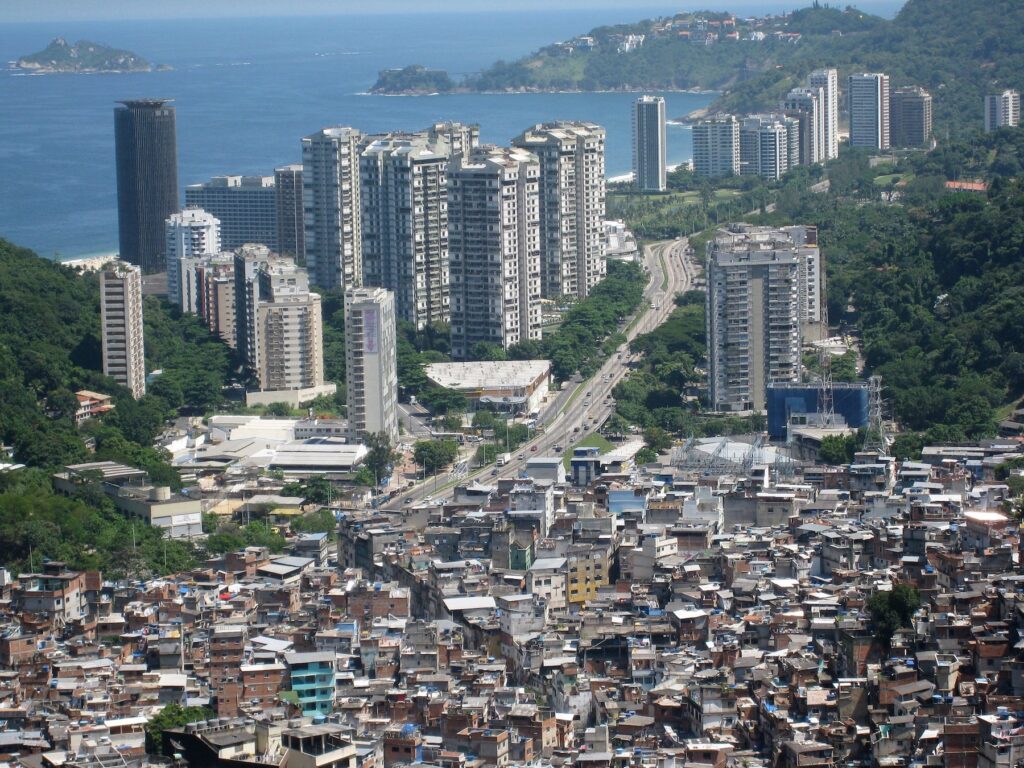

One of the starkest examples of this forced ghettoization is in the neighborhood of Juhapura, often derided as the “mini-Pakistan” of Ahmedabad city because of its significant Muslim population. In reality, the neighborhood reflects the deep segregation of an embattled community, often denied housing and socio-economic upward mobility in the more upscale, largely Hindu-inhabited residential neighborhoods. Researcher Laliwala emphasized this, and pointed out how the Disturbed Areas Act has made Ahmedabad the most segregated city in India on Hindu-Muslim lines. “This is evidenced not only in the creation of a ghetto like Juhapura – perhaps one of the largest concentrations of Muslims in India in a single locality,” Laliwala noted.

It is amidst this climate of segregation that the state recently held elections in December 2022. No mainstream political party in Gujarat prioritized the state’s Muslims or the abject housing discrimination that persists. The lack of adequate political representation of Muslims, both in Gujarat and now increasingly at the national level across India, has compounded the problem. While the political erasure of the country’s Muslims from mainstream and secular political parties looms large, challenges to this law have come from a handful of human-rights activists, lawyers, and Muslim political factions.

But even as the fight against this legislation goes on, today, the situation looks bleak. A weary Amir Petiwala sums it up best: “The bottom line is, Muslims are being completely deprived of buying a place to live with their families in a decent area of mixed religions,” he says. “And the worst part is, there is absolutely no representation of our voice in the local political platform.”

And to many observers, the enforced religious segregation in Gujarat is only likely to expand throughout India.

Today, India’s mainstream news media is amplifying far-right allegations of “Land Jihad” across the country. In the country’s mountainous northern and north-eastern states of Uttarakhand and Assam, political leaders affiliated with the ruling BJP objected to Muslims buying property and accused them of trying to push Hindus out and capturing “their” land. In 2021, the cosmopolitan city of Gurugram, near the country’s capital, saw protests against allowing Muslims to pray in open spaces. Now, there are reportedly only six spots in the city where the prayers can be offered, down from 150 such spaces as of 2018. With this increasing spatial segregation against Muslims, Gujarat’s story may be a bleak sign of things to come throughout India.

Sabah Gurmat is an independent journalist based in Mumbai, India. She writes on issues of human rights, law, tech and culture.