Not So Sorry

Fetishizing Forgiveness

Expecting people to forgive in all situations can enable abuse and allow social injustice to continue

(Image source: BBC/Getty Images)

House cats may spend most of their days asleep, but when they’re awake, they’re likely to spend at least some time fighting one another. Competition in the natural world for food and territory may be a far cry from a comfortable life of puffy sofas and regular feedings, but animals still feel a need to battle it out. But no matter the species, even if they bite hard enough to draw blood, animals usually seem to forgive one another.

Anyone who’s watched a nature documentary knows there are exceptions. Sometimes animals fight to the death. More typically, fights end quickly, and the herd goes back to grazing or hunting. Sometimes animals become enemies for life. But they mostly return to being compatible.

This may not be what we think about in the larger scope of conversations about forgiveness. But our hominid ancestors lived in tribes, and we are still animals. Moving quickly past conflict made our survival as a species possible because we learned how to stop fighting before we killed one another. In any competition for survival, a pack is more likely to survive than a solitary animal. It could be argued that forgiveness is hard-wired into our DNA.

Yet the reason we evolved as a species from swimming to crawling to walking is because we were willing to override our genetic code. We learned to forgive to protect the pack, but we also learned when a pack member could not be forgiven. In those same nature documentaries, you might recall the solitary animal, cast out on its own, wandering the wilderness. That is the unforgiven animal. And revenge or retribution might be as deeply embedded in our genes as forgiveness.

But what do we really mean when we talk about forgiveness? The understanding most of us have is that forgiveness is essentially a kind of moral gift, granted to someone who has wronged us. There’s also a common notion that we somehow “forgive and forget,” moving past harm and leaving it behind, which is often far from our lived reality. Forgiveness is often portrayed as something that will help a person turn their life around. Seemingly every religious tradition describes forgiveness as a virtue. Muslims refer to Allah as “Ghafir,” or all-forgiving. In the Dharmic religions of Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism, seeking forgiveness is an important step toward both mental clarity and cultivating compassion. Judaism’s focus on forgiveness is so paramount that many regard Yom Kippur, literally “Day of Atonement,” as the holiest day of the year.

Christianity, however, is what shaped much of Western thinking about forgiveness, and nearly every classic work of literature, film, theater, and music made by Christian or lapsed Christian artists has involved some portrayal of forgiveness. In America in particular, our collective imagination is shaped by the idea that forgiveness is a virtue, and failing to forgive is a vice, sin, and failure.

Up until the 20th century, when psychology evolved into its contemporary form, how people understood forgiveness was rooted in philosophy and religion. And both of those continue to influence how we talk about forgiveness today. In essence, our understanding of forgiveness often lands in the middle of a Venn diagram of philosophy, psychology, and religion. Plato and Aristotle, the founders of Western philosophy, saw controlling anger as important to leading a virtuous life, and understood forgiveness as a route toward freeing a person from anger. But as Christianity evolved and conquered, forgiveness itself became a virtue, and failing to forgive became a vice.

(Scene from Promising Young Woman)

On the opposite hand of forgiveness is revenge. And depictions of revenge can be a highly enjoyable way for us to live out the fantasy that we might get our own retribution instead of being forgiving. In the 2022 film The Banshees of Inisherin, a conflict between old friends escalates to absurdist levels of violence as the two men trade acts of revenge. At the end of the film, Pádraic, whose house has been burned down by his former friend Colm, says “some things there’s no moving on from, and I think that’s a good thing.” In 2020’s Promising Young Woman, a former medical student whose friend was raped by a classmate systematically takes revenge on everyone from the school who colluded to cover it up. In 2002’s Oldboy, a man freed from prison after many years for reasons he doesn’t understand sets out on several acts of revenge. And even 1980’s classic comedy 9 to 5 is about a group of women who get revenge on their misogynistic boss.

These movies are enjoyable because they are a kind of wish fulfillment. Instead of being forgiving, the characters get what most of us really want deep down inside when we have been wronged, which is to hurt the person who did it. Sublimating that instinct for revenge is one of the great battles of our lives. The difference between us and our house pets is that we keep thinking about being wronged long past the event itself, sometimes for years or decades.

Revenge fantasies are an escape from the reality that forgiving is sometimes just more pragmatic. But the fact is that while forgiving one another may be part of what keeps our world from tumbling into violence, it is not always as easy as we are taught. And it is not always possible.

While many portrayals of forgiveness focus on reconciliation, with the offender being welcomed back into a relationship, modern philosophers like Jean Hampton have argued that reconciliation can be “morally unwise.” If the offending party isn’t asking to be forgiven, offering forgiveness can put the victim in a more vulnerable position. This is closely related to cycles of abuse in domestic and institutional relationships. If a victim is always forgiving, the offending person is essentially given permission to keep harming. A tendency to rush to forgiveness can also indicate a lack of self-respect, because the individual who does this may struggle to understand that sometimes forgiveness isn’t actually owed.

Some philosophers also argue that forgiveness cannot work unless it comes with conditions. Charles Griswold writes that it is the wrongdoer who is responsible for fulfilling the conditions for forgiveness. In Griswold’s argument they must acknowledge they’ve done wrong, repudiate what they’ve done, express regret, commit to change, show they understand the damage they’ve done, and explain why behaved poorly in the first place.

But even if reconciliation isn’t always possible, philosophically, “reconciliation is the goal to which forgiveness points.” The animal kingdom example works again here. The pack is stronger when reconciled. It will survive. The same can be argued for nations struggling to move past painful episodes in their histories. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which shed light on the atrocities of apartheid, worked to demonstrate that unless those atrocities were made public, reconciliation would never really be possible, and the nation would never be unified.

For many religious people, divine forgiveness can be difficult to grasp and explain. Who can really know the mind of God? If forgiveness is in God’s hands, as Jesus says on the cross, how does one know when or if God has forgiven? The truth is that one can’t and doesn’t know. We can only assume that some combination of atonement, right behavior, amends, and apology will get us close enough for God to grant us forgiveness. In Catholicism, the priest, acting “in persona Christi,” does the forgiving on God’s behalf in the sacrament of reconciliation, more commonly known as confession. But forgiveness in confession always comes with penance of some sort, or else, the church teaches, it doesn’t work.

There is also a performative kind of forgiveness, where a person asks for forgiveness but is essentially unchanged when granted it. If forgiveness means moving past and letting go of resentment toward someone who’s wronged you, as many philosophers and psychologists agree, that assumes that the person being forgiven is actively working to avoid making the same mistake again. This, of course, is far from reality in many cases.

But who is forgiveness really for? In philosophy and religion, art and literature, forgiveness is often depicted as liberating for the person who has done wrong. But modern psychologists have begun to focus instead on the idea that forgiving is about liberating the person offering the forgiveness from resentment, anger, or a desire for revenge. If holding on to grief or pain can lead to resentment, which can be psychologically damaging, forgiving someone could theoretically be an end to that resentment. In this framing, the person doing the forgiving is who benefits the most.

The psychologist Fred Luskin, who formerly ran Stanford University’s Forgiveness Project, says that learning to grant forgiveness is a way of understanding that being told “no” is a universal experience. According to Luskin, “the essence of forgiveness is being resilient when things don’t go the way you want.” Learning to accept that things are not always as we hoped is a key to moving past resentment and into forgiveness.

But Luskin contends that you cannot forgive someone without grieving. When someone does us wrong, we must recognize that our relationship is forever changed, and we have to grieve that change. Instead of letting go of the experience, Luskin says allowing ourselves to grieve helps us transform our emotional response to it, which can help us to become more resilient and more forgiving. He also maintains that not hiding the process you’re experiencing is crucial. Research has shown that people who experience trauma and don’t share that experience have worse outcomes than those who do. This may be why sexual abuse victims find it so difficult to arrive at forgiveness, since shame and secrecy are inherent to many cases of sexual abuse.

The former pope Benedict XVI died while I was working on this essay, and the knowledge that he had failed to act to end sex abuse by priests in Germany while he was an archbishop overshadowed every word of praise I saw lavished on him in obituaries and on social media. Children were raped while he stood by and did nothing. Why were people so forgiving of a person who’d colluded to allow that to happen?

Because the sexual abuse atrocities were so shameful, they had stayed a secret until Benedict retired from the papacy and were not made public until the same year he died. Among the eulogies praising his theological mind and his love of music and art, the voices of abuse victims were hardly heard at all. It’s likely they had not forgiven him.

If psychologists argue that learning to forgive benefits the person who has been wronged because it allows them to move past resentment and into freedom from mental burdens, the problem is that memories of a traumatic event can last for the rest of a person’s life. Sex abuse victims have talked extensively about this, as have war veterans, and many other people whose bodies and minds have been violated.

When it comes to people who are not able to forgive, some psychologists argue that this may actually be a way of protecting themselves from further harm. Jeanne Safer, author of Forgiving and Not Forgiving, argues that “enshrining universal forgiveness as a panacea, a requirement or the only moral choice, is rigid, simplistic and even pernicious.” Yet, according to Safer, we have come to expect forgiveness to be granted so universally that we demonize anyone unwilling to grant it. The problem here is that we equate forgiveness with a kind of moral purity that few people can live up to. In her reading, there are actually many cases when not forgiving someone is the most appropriate action to take.

Safer describes three types of people who withhold forgiveness. For the first type, “moral unforgivers,” refusing to forgive means telling the truth, asserting fundamental rights, and opposing injustice. “Psychologically detached unforgivers” accept the painful reality that they cannot experience any positive internal connection with a betrayer, which forgiving would require. And “Reformed forgivers” have faced conflicts between feelings, religious principles or ethics, and have come to reject the conventional attitudes they once accepted. But none of these three types of people is vindictive or against forgiveness in principle. They share the capacity to forgive, but have come to a decision that forgiveness, rather than freeing them from patterns of negative thinking, can further damage them psychologically.

In Safer’s telling, the decision not to forgive can sometimes be liberating for the children of abusive parents. This does not mean those people necessarily cut off all communication or refuse to acknowledge a parent, but that they are “outraged but not obsessed” by the harm done to them. When people insist on universal forgiveness, it can blind them to the fact that reconciliation without forgiveness is also a viable possibility.

The pandemic has also revealed fault lines in our understanding of forgiveness. In the most recent season of the podcast Serial, the poet Rachel McKibbens tells the story of how her father and brother both died from Covid just a few weeks apart. Her father, who had been physically abusive to her and her brother throughout their childhood, still displayed qualities that caused both Rachel and her brother Peter to stay in touch with him as adults. Their father took them in when their mother put them in foster care. He supported Rachel’s interest in acting and theater and drove her to rehearsals all over the Los Angeles area. He loved movies and watched them with his kids, and was scrupulous about making sure they were well fed. But he drank, and when he drank, he got violent. Rachel and her brother, like many children of abusive and alcoholic parents, became a team and paired up together against their father’s rage.

When Rachel grew up, she moved across the country. But her brother moved back in with his father, and tried and failed to get him to stop drinking. When Covid arrived, both father and son refused to get vaccinated. They began to tunnel down rabbit holes of conspiracy theories about vaccines and the government, fueled by texts from a cousin. Her father refused to go to the hospital when he got Covid, and he died at home. Shortly after, Peter’s health rapidly declined as well.

As Peter’s own Covid case got worse and he became feverish and short of breath, he called his sister. Rachel told him, “If you don’t go to the E.R. right now, I will not forgive you when you die.” Peter went to the E.R., where he was put on oxygen, but he refused medication because he believed a conspiracy theory that doctors receive money if they give medication to Covid patients. He told his sister he was released because he was getting better, but this was a lie. He had discharged himself against medical advice, went home, and died. He was 44 years old.

Three years into the pandemic, there are millions of stories like this. Rachel says she herself feels like she needs forgiveness for not pushing her father and brother harder to get vaccinated. But at some point, when a person refuses to get help, even to get something as simple as a vaccine, they move past being forgivable and into a messier, greyer area.

During the AIDS epidemic, millions of people were abandoned by their parents and families because they were considered untouchable. But it was the enraged, unrelenting pressure from gay men, at that time the most at risk of contracting the disease, which pushed the American government and pharmaceutical companies into funding medical research to make lifesaving drugs affordable and accessible. Some of those same men who survived AIDS never forgave or reconciled with the families that rejected them.

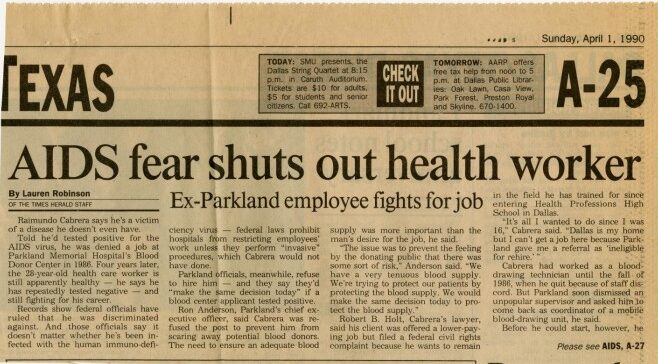

(Dallas Texas Digest headline from April 1990)

Today, untold numbers of queer and trans kids are also rejected by their families of origin, and they, too, struggle to feel forgiving. But if they cannot bring themselves to forgive the parents who rejected them, does that make them bad people? I know far too many people who fit these descriptions, who cannot forgive their parents and have had to self-create families that would be more understanding and supportive. In no cases would I describe them as “bad.” They are, in fact, some of the most empathetic and compassionate people I’ve ever known.

Perhaps, for some people, forgiveness can be freeing. But in cases where it would do further damage, enable abuse, or cause someone to engage in self harm, forgiveness can do the opposite. It can put us into a moral cage of “goodness” where we become trapped by the idea that failing to forgive means we are fundamentally bad people. And this is particularly true among Christians in America. Decades of the rise of fundamentalist thinking about Christianity have led people to believe that Jesus always preached forgiveness, that he demanded it, and that failing to give it makes you a bad Christian and even an apostate.

But American Christian ideas of forgiveness are also shaped by our country’s history of believing in predestination, manifest destiny, slavery, colonialism, misogyny, homophobia, and many other social ills that have become deeply intertwined with Christianity. The idea that forgiveness must be universal is cross denominational, too, impacting every American Christian from Catholics to Protestants, from overwhelmingly white Mormons to Black Christians who belong to churches founded by slaves.

Just as our nation both insists it believes in the separation of church and state and demands lawmakers to take an oath of office with one hand on a holy book, we fetishize forgiveness, but we also have the highest incarceration rate in the world. The death penalty is legal in 27 states. Families trying to cross the border into the United States, often fleeing abuse and violence, are put into cages or detention centers where they lack adequate food, medicine, and water. And a woman seeking an abortion because of an unplanned pregnancy will be unable to get one in thirteen states as of this writing, and likely many more in the future. We are not a forgiving nation.

But it needs to be clear that as the author of this column, I am not against forgiveness. Forgiveness can indeed be liberating. It can mend relationships, heal emotional wounds, and make us feel better about ourselves. But expecting universal forgiveness can also give abusers permission to keep abusing. It can cause self-harm. It can lead to suicidal ideation and addiction. It can also drive people away from religion when religion makes them feel like failures for being unable to forgive. Forgiveness is something that should improve our lives and our society, but America today is a stellar example of why this is very much not the case. We need to see that forgiveness has limits, and that for our own good, we sometimes need to heed them.

Kaya Oakes is the author of five books, most recently including The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life’s In Betweens to Remake the World. She teaches writing at the University of California, Berkeley.