Fate on Hold: Jewish Collectors at War

What do we save? And for whom?

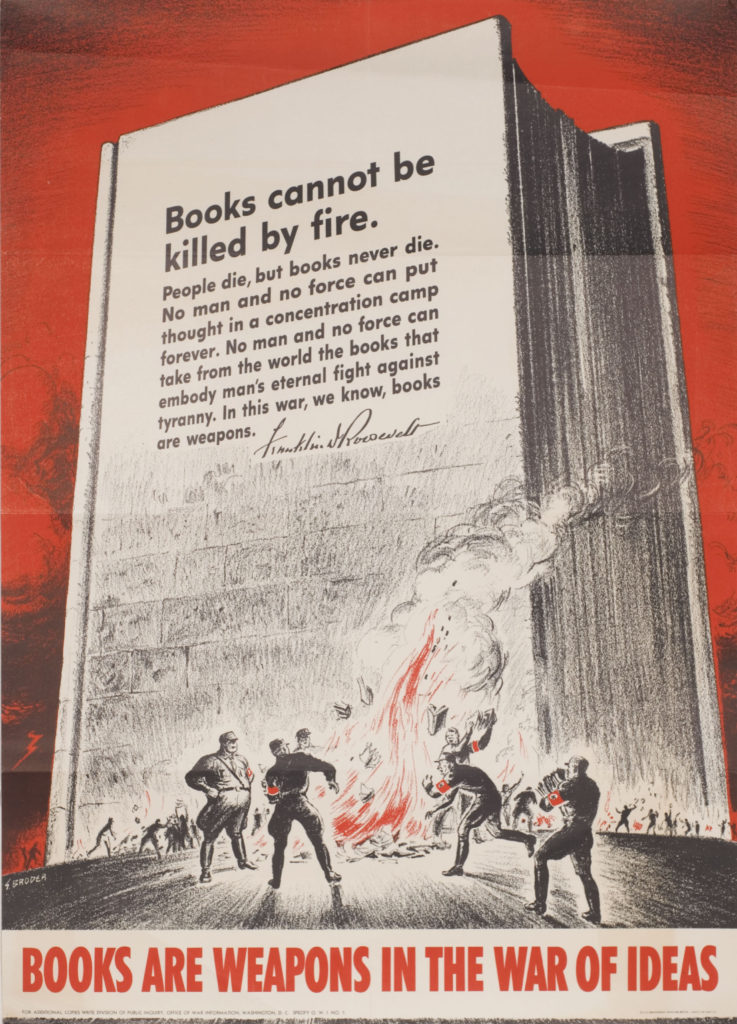

Books are Weapons in the War of Ideas, Steven Broder, 1942.

The library is burning. What do you save? It isn’t just a parlor game for classicists showing off their erudition (a game that has been played since the classics themselves, like Athenaeaus of Naucratis c. 200 C.E., who peppered his learned banquet-scenes with lost books from the Library of Alexandria).[1] It figures in ancient cultures’ founding myths. From Aeneas bearing Troy’s gods out of her burning ruins to the inflammable books of Irish saints,[2] the trial by fire purifies, elevates, sets us apart. What do you save? Tell me your answer, the myth murmurs, and I’ll tell you who you really are.

In Jewish culture, the question has a particularly resonant and painful ring. Jews have long been called a “people of the Book,” but one could just as easily say that Jewish books are people. Authors dissolve into their books: rabbis are often renamed after their best-known title, and Yiddish authors play with meta-pen-names like “Mendele the Book-Monger” or “A. Pen.”[3] Scrolls, like bodies, circulate in the symbolic system of purity.[4] So early rabbis weren’t playing a parlor game when they first posed our question around the same time as Athenaeaus’ banquet. “All sacred writings are to be saved from a fire,” they answered. But this raised new problems. What makes a book sacred? Is it the book’s language? Its contents, ink, pages? How it is used? How should we weigh sacred books against other things worth preserving (like studying Oral Torah or keeping the Sabbath)?[5] As the argument continued, it took on a more heated tone: whose books do we save? Books of Jewish heretics (later read as “gospels”)? Hell no, let them burn. But they contain names of God; aren’t they sacred too? Fine, cut out the names and leave the rest… Rather than a founding myth, the question started an argument about the canon and the limits of community. The library is burning. What do you save–or whom?

If canon and community are defined by what we preserve, not only by what we create, then we should give more credit to the role of the collector: keeping chaos at bay, reigning in entropy, digging the wells of collective memory. For the most part, their genius lingers in the halls of museums and libraries, absorbed in labors—gray, meticulous, detailed—known only to their peers. As custodians of the past, sweeping away their own fingerprints is part of the job. In a crisis, however, the ancient question weighs heavily on their shoulders. What, whom do we save? And for whom? The latter is the question at the center of two recent histories of Jewish collectors of the Holocaust era. Like early rabbis, these collectors ended up arguing not about the flames, but about the ashes; they asked not whether to save the past, but which Jewish community should rise, Phoenix-like, from its remains.

***

At first, that question did not preoccupy the “paper brigade,” heroes and heroines of David E. Fishman’s new book on cultural preservation in the Vilna ghetto (The Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the Nazis). They were well aware that they might not survive, so they decided to save as many Jewish items as possible, at any risk and many costs (like smuggling less food for themselves and their families). In sensitive and thrilling detail, Fishman describes how they stopped the Nazis from looting all of their community’s heritage: distracting a guard by giving him free tutoring, or schmoozing their way through the ghetto gate arm-in-arm with an oversize Talmud folio. Under a regime that sought to reduce Jewish people to bodies, Fishman shows how effectively ghetto collectors turned the book into a symbol of their people’s spiritual survival.

There is nothing obvious about this. Yes, Vilna, the “Jerusalem of Lithuania,” was a bookish city, one of the most culturally important Jewish centers in the world. Yes, many peoples have struggled for their literary heritage in extreme conditions (The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu under ISIS, for example). But it is one thing to value books and quite another to make them a measure of human value: to say, as one member of the paper brigade to another, that the better poet should keep the gun. Nor were books given such value only by the Jewish elite. The prewar efforts of Jewish historians and ethnographers had already produced the figure of the zamler (“collector”), a scholar or person of any education level who gathered raw materials for Jewish research. Zamlers kept up their work during the Shoah, with no tangible incentives, helping to build Vilna’s great institutions like the Jewish Scientific Institute (YIVO). Why? If a 1929 YIVO handbook for zamlers is any indication, they couldn’t quite say.[6] “What is the point of all this foolishness?” the zamlers ask, even as they bend down to pick up another book.

Such is often the case with any culture’s totems, its most intensely compressed symbols. If you ask someone in the culture why they are so important, they shrug: “Because it’s what we do.” Yet this just-so sense of things is usually the first victim of a crisis. For Vilna’s collectors, then, books became a way to preserve not only the past but also the everyday order of the universe. Like the sign on the ghetto library wall (Books are our greatest comfort in the ghetto!); like the ghetto militia awaiting their last stand and reading aloud from a novel of the Armenian genocide; like the Jewish library worker to whom a Haggadah’s illustrations of slavery so powerfully echoed the Nazi project that he tried to destroy it; and like the father who hid his daughter’s body underground until he could bury her among Torah scrolls, we come to see the book as a symbol that points beyond itself: into a future where continuity with the past, and thus a vital Jewish community, will return. Sutzkever, a great Yiddish poet and a member of the paper brigade, captured this vision in an image from his beloved natural world, the “seed of wheat”:

And as the primordial seed

Outstripped its hull, became an ear

So shall they nourish and endure

Forever in the people’s feet

The words, immortal words, are ours

Yet no vision of community is natural. In the ghetto, books became a source of resolve, dignity, or escape: an “oasis of freedom” in the words of anthropologist Daniel Feinshtein (who did research on books in the ghetto as a real-time participant-observer and lectured in its library). Already, however, cracks were starting to appear in and around the paper brigade. They agreed on what or whom to save: as much Jewish material, as quickly as possible, especially unique artifacts or papers like Theodor Herzl’s diary. But for whom? Whose Jewish community?

Fishman shows the very different responses of four figures: the prophet, the academician, the Zionist, and the communist. Kalmanovitch, the “prophet of the ghetto,” put his faith in the future. The Nazis were bound to lose the war, so it was just a matter of time until the books were returned. Meanwhile, the safest place for them was Germany. This view led him to waver in his support for smuggling and drew criticism from others in the paper brigade. Kalmanovitch turned out to be right (although the Nazis destroyed upwards of 70% of the materials), but he was no pragmatist. He simply held onto his faith that the apocalyptic “War of Gog and Magog” would pass, and fueled resistance by creating a symbolic outside to the ghetto: a better time, a better place (“I have a son in the Land of Israel”), and a sense of hope (“sadness is the nullification of existence”).

The academician, Max Weinreich, lived another story. First of all, he lived; in New York, where he relocated YIVO and the fallen sparks of its Vilna collection after the war. But rather than prophetic faith, Weinreich responded with historicist fervor. He kept hunting for the rest of YIVO’s looted collection. As he did so, he wrote a landmark book where he broke with his native German language and its scholarly tradition (Wissenschaft).[7] Weinreich emphasized how many German academics had been co-opted by the Nazi regime. But Fishman, without further ado, expands Weinreich’s claim into a claim about the essence of modern German scholarship (“Wissenschaft had betrayed him”). Many German Jewish scholars and their non-Jewish colleagues drew just the opposite conclusion. For them, the Nazis had soiled the bathwater, but the baby of Wissenschaft was alive and kicking.[8] By throwing both out together, Weinreich was not only rescuing Jewish books from German scholarship; he was building a new community around a new kind of Yiddish scholarship.

Zionists fought alongside socialists and Communists in the Vilna ghetto. The leader of the partisan militia, Aba Kovner, collaborated with the paper brigade to get a bomb-building manual. But after the war, Kovner had his own idea about who deserved the books that they had saved. He lifted materials for Israel, eyes set on the crown jewel of Vilna’s book collectors: Herzl’s diary. When fellow partisan Shmerke Kaczerginski found out, he told the occupying Soviet authorities. Kovner narrowly escaped arrest without the diary, which ended up in New York (where it proved too un-Zionist for the Forverts editor to publish). Fishman moves quickly to absolve Kaczerginski, but this ugly chapter should give us pause. To see men fighting together for Jewish books and lives, only to apparently threaten each other’s lives over books, points to deep divisions between them—and their communities—that war had merely papered over. Whose books are they, really?

As a communist, Kaczerginski was in for his own rude awakening. He stayed in Vilna and started a museum to rebuild Jewish culture, despite constant Soviet and Lithuanian harassment. But when tons of Jewish books and documents that he had saved were sent off to the paper mill, and his desperate rescue efforts were chided by a bureaucrat for not following proper procedure, his communist spirit broke. Re-traumatized by what he called a second “crematorium,” he chose to move the surviving materials to YIVO in New York. He succeeded–Fishman’s book, full of unforgettable images, has a photo of YIVO scholars unpacking the crates in a Manischewitz Matzo warehouse–but Jewish communists saw him and Sutzkever as traitors. They accused Sutzkever of being “a thief, not a rescuer”; at his Paris apartment, he feared break-ins, while at YIVO in New York, Weinreich worried about demands to extradite the materials. Even Nazis had agreed that some Jewish books were worth saving; the fight, as ever, was about who deserved to be their readers.

***

A thief and a rescuer are also the main characters of another recent book on Jewish collecting in this period, by Lisa Moses Leff (The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust). The trouble is, they’re the same person. By focusing on the Janus-faced figure of Zosa Szajkowski, a man who was equally prolific at saving, cataloguing, and then redistributing the sources of French Jewish history, Leff tells a less unambiguously heroic story than Fishman’s about the same fundamental question.

The question is not why Szajkowski stole so much from European archives after the war and sold his contraband to U.S. libraries. It boosted his fragile ego; besides, he needed the money. Force of habit also played a part: after earning kudos from famous historians like Elias Tcherikower and Weinreich as a wartime zamler, Szajkowski had a hard time getting out of character. Storming Berlin in U.S. uniform, he fell into a collector’s bloodlust; sending letters in Yiddish on Hitler’s stationery, pilfering antlers from Goering’s hunting lodge, and keeping a mummified woman’s head for himself. This, too, makes weird psychological sense. Never really part of the Jewish scholarly elite, full of rage at what was taken from him, Szajkowski became a sympathetic thief, but a thief all the same, who drowned himself in a hotel bathtub when the shame of exposure proved too much to bear.

As a historian, Leff deftly turns her own biographical answers into an open question. Who really owns the Jewish past? For whom is it worth saving? Like Fishman, she studies the line between thief and rescuer, looter and zamler, as it was smudged and redrawn in this chaotic era. In the process, everyone staked a claim to the kind of community that the Jews should become. Yet those claims shook out differently in Szajkowski’s context, that is, the Jews of modern France. In France, more than in Eastern Europe, a secular national vision of Jewish community continued to compete with others (Zionism, Marxist internationalisms, and diaspora nationalism). Even as they stared Vichy collaboration and anti-Semitism in the face, a generation of French Jews stayed in limbo. Did they belong to France, to Israel, to the workers of the world, or to Jewish culture?

This oversimplified form of the question brings out the major argument in Leff’s narrative. Despite all the chaos and entropy behind the scenes, the French national archive, with its “façade of completeness and order,” has a powerful grip on other ways of defining Jewish community. In this postwar context, Szajkowski becomes a canary in the mine of secular nationalism, a tragic symptom of its dominant order who shows the limits of the kind of Jewish history that it supports. The book smugglers are to Nazi dehumanization as the archive thief is to French assimilation.

Leff’s antihero exposes a hole behind the archival façade: the very idea of a secular nation relies on the fiction of historical continuity with fellow citizens and a shared past. Yet in order to enforce this continuity, the state cuts the ties that bind minority groups. For French Jews, struggling to document their persecution and rebuild their institutions after the war, that cut could be brutal. Between 1944 and 1947, French state agencies were ordered to destroy all records identifying citizens by race. Officially, this was in order to roll back the unpatriotic effects of wartime racial laws on the nation. But in the name of protecting Jews from more persecution, the state used archives to cover its tracks. Many documents of French Jewish history were destroyed–documents that could have been used to punish collaborators, seek reparations, and offer evidence for Jews’ own internal courts. Similarly, France and other Allies chose not to label former concentration camp inmates as Jews. Due to this “race-blind” intake policy in occupied Germany, Holocaust survivors were denied recognition that might have saved them from dire conditions. The insight of Tcherikower (Szajkowski’s mentor) about Jews in post-revolutionary France still held true in the post-Holocaust era: so-called emancipation mainly benefited the secular state, at the cost of Jews’ ability to claim rights as a community. Ironically, the state’s fiction of continuity made it easier for Szajkowski to pillage its archives. For decades, archivists hardly took stock of what had been lost. Nor were they able to notice his theft. Blinded by nationalist codes of classification, they were unable to see any pattern among the papers that he plucked out one by one: a (Jewish) debt record here, a decree on (Jewish) usury there… No wonder that when he was finally convicted, a French court portrayed him as a “wandering Jew”; this archive thief embodied the return of everything that the secular nation had repressed.

But what did Szajkowski stand for? For whom, other than himself, did he save or steal so much French Jewish history? A relentless eccentric autodidact born poor in Poland, who served in both the French and the U.S. armies, who never held an academic position for long, who was not a religious man, he seemed to love only a few women, teachers and colleagues, and his books. Again, Leff rightly goes beyond his biography to consider the implicit ideals of Jewish community guiding his decisions. Her arguments, however, lead in two contradictory directions. The stronger direction is diaspora. In diaspora, defined as a positive identity rather than merely as a temporary exile, Jewish community does not need the state. Jews are bound together by being Jews; a moral community that is as hard to pin down as the Yiddish word yidishkeyt (“Jewishness”) is to translate. Historically, its privileged form has been the book, or what Heinrich Heine called a “portable homeland.”[9] In the book, unlike the state archive, a diaspora community arranges and rearranges its own past. Leff sees this diaspora ideal in Szajkowski, who himself compared Tcherikower’s notes for the massive documentary project Jews in France to the Mishnah that early rabbis took from the Land of Israel to Babylonia.[10] By this logic, the books and documents that Szajkowski collected were also a portable homeland: a “weapon of the weak” to preserve Jewish history where the archives saw only French subjects.

In the other direction, Leff occasionally lets the logic of modern nationalism obscure the idea of diaspora, as if she does not quite believe that Jewish history can be written without the state. Of Jewish historians in the 1930s–like Tcherikower, and Kalmanovitch of the paper brigade—she claims that their “commitment to study as a way to solve Jews’ present problems had led them to a deeply problematic stance.”[11] For Leff, the problem is that they were too traditional to adopt modern political ideals, yet too modern to return to the traditional life that they studied. Having imposed this dichotomy on the sources, she reads their credo (Return to the ghetto!) as a “tragedy” due to “nostalgia” for the “enchanted worldview” of Jews in the traditional past, one that they lost “in spite of themselves” out of their modern commitment to “reasoned debate [,] scholarly inquiry [and] the power of the individual.”[12] Yet Jews valued all those things long before modernity. Nor has the ghetto been only a negative space of Jewish exclusion from modernity.[13] The choice that these scholars faced was not between modern nationalism and a self-defeating individualism. They chose a portable homeland and a space outside the state—a cultural diaspora.

Like his angel of history gazing down at the rubble of civilization, Walter Benjamin’s spirit hovers over Leff’s story of the archive thief and this larger story of Jewish collectors in the Shoah. She ends by alluding to Benjamin’s vision of history, not as a well-ordered archive, but as a “salvage heap.” This is a valuable corrective to the violent fiction of continuity that sustains modern nationalism, reminding us that forms of the Jewish nation are constantly made and unmade without the state.

But, Leff knows, there is more to Benjamin than this. She begins her story with his essay “Unpacking My Library,” where each title opens onto a vast storehouse of jumbled memory. “Books have their fates,”[14] Benjamin remarks, in a carefully fractured allusion to The Anatomy of Melancholy (“Books, according to their readers’ capacities, have their fates”). Whose fate: the book’s or the reader’s? The essay works to negate any distinction: it ends with his collector vanishing into the last half-empty shelf. Books are political but, Benjamin seems to be saying, they are people too, and their meaning is personal or it is nothing. Perhaps this is why it shines brightest at dusk, at a historical moment when the truly personal collector is replaced by the engines and fires of the state. “Only in extinction can a collector be comprehended,” he concludes, not long before the books begin to burn.

Is collecting, under these conditions, a tragic and nostalgic form of modern Jewish culture; a merely personal assertion of “meaning” in a world that no longer knows or cares what it means? Or is it a political project, forcing order on chaos to trumpet one definitive vision for the nation? It’s hard to hold a space between the future and the past, but that’s what the Vilna ghetto library, like Benjamin’s library, became: spaces where personal and political drives were ever present, yet restrained by a hushed concentration that borders on the sacred.

Although he crossed them out and they would not appear in the second German printing or subsequent translations, Benjamin evoked this more directly in the final lines of his manuscript to “Unpacking My Library”:

O bliss of a collector, bliss of being left alone! Is that not the consolation which governs all memories? In our memories, to be left alone with existence, still and silent, watching over us. To know of everyone who surfaces here that they, too, will accept this crisp and reliable silence. A collector puts his fate on hold…[15]

The silence is worth keeping too.

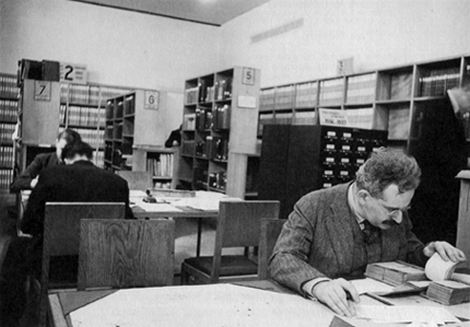

Walter Benjamin in Paris, 1937. Image © Gisèle Freund

***

[1] See Lucien X. Polastron, “A Short History of the Census of Lost Books,” in his Books on Fire, trans. Jon E. Graham. Vermont, 2007: 316-21. For Jewish books lost during the Holocaust, see Joy E. Kingsolver and Andrew B. Wertheimer, “Jewish Print Culture and the Holocaust: A Bibliographic Survey,” in Jonathan Rose ed., The Holocaust and the Book: Destruction and Preservation. Amherst, 2001: 295-310. I thank Brad Sabin Hill for the latter reference.

[2] Sources at Tom Peete Cross, Motif-Index of Early Irish Literature. Bloomington, 1952: 335.

[3] S.J. Abramovich (d. 1917) and Joseph Opatoshu (d. 1954), respectively. For research tools on Hebrew and Yiddish pen names, see Zachary Baker.

[4] See Florence Heymann and Danielle Storper Perez, eds., Le corps du texte: pour une anthropologie des textes de la tradition juive. Paris, 1997.

[5] See Marc-Alain Ouaknin, The Burnt Book: Reading the Talmud, trans. Llewellyn Brown. Princeton, 1995 [1986] and this study by Shamma Friedman. (All translations mine).

[6] See Naftoli Vaynig and Khayim Khayes, “What is Jewish Ethnography? (Handbook for Fieldworkers),” trans. Jordan Finkin. In Andreas Kilcher and Gabriella Safran eds., Writing Jewish Culture: Paradoxes in Ethnography. Bloomington, 2016: 349-80.

[7] In Weinreich’s footsteps, Fishman writes several German words as if they were Yiddish: the Reichsstelle für Sippenforschung becomes “Reichstelle fun Sipenforschung” (p. 108), Deutschland über alles becomes “Deutschland uber Ales” (p. 28) and is characterized by Fishman as a “Nazi song,” though it dates back to Weimar and is still the national anthem.

[8] Weinreich, as Fishman notes, earned a doctorate at Marburg; in 1923, two years before Jewish literary scholar Leo Spitzer joined the faculty. Yet for Spitzer and other Jews at Marburg, especially Erich Auerbach, wartime persecution only intensified their faith in the Wissenschaft ideal. Non-Jews at Marburg rose to its defense as well: E.R. Curtius published anti-Nazi polemic, Traugott Fuchs supported Spitzer and had to go to Turkey, Werner Krauss was sentenced to death for treason. Another good contrast to Weinreich is Victor Klemperer, who barely survived the war and, like him, wrote a searing critique of language in the Third Reich—in German.

[9] Daniel Boyarin, A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora. Philadelphia, 2015.

[10] Leff, Archive Thief, 55: ” ‘Our dear friends left France by foot, with a small package in their arms–a few draft pages of our planned Paris YIVO writings. This is how our forefathers left for Galut [exile].’ ” By this analogy, New York is not “Yavneh” as Leff says (the city where rabbis regrouped in the Land of Israel), but rather Sura, in Babylonia.

[11] Leff, Archive Thief, 43.

[12] Leff, Archive Thief, 45.

[13] Daniel B. Schwartz is completing a history of the term “ghetto”; for now, see his talk here. For a classic study of its complex social role see Louis Wirth, The Ghetto, Chicago 1928.

[14] Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften IV (2 vols. in 1), ed. Tillman Rexroth (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1972), 389.

[15] Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, 998.

***

James Adam Redfield is Assistant Professor of Biblical and Talmudic Literatures in the Department of Theological Studies at St. Louis University. His research focuses on ethnography in rabbinic literature, including the study of ancient rabbis as collectors. He teaches graduate/undergraduate courses on premodern ethnography and travel; the Hebrew Bible; and comparative courses on premodern Judaism and Christianity. James has also published several translations from German, French, and Yiddish. He is currently translating a volume from Yiddish by Micah Josef Berdyczewski (to be entitled Letters from a Distant Relation and supported by the Yiddish Book Center).

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.