Evangelicals Make Themselves Essential to the Next Insurrection

What the documentary “The Essential Church” reveals about evangelical hostility toward the government

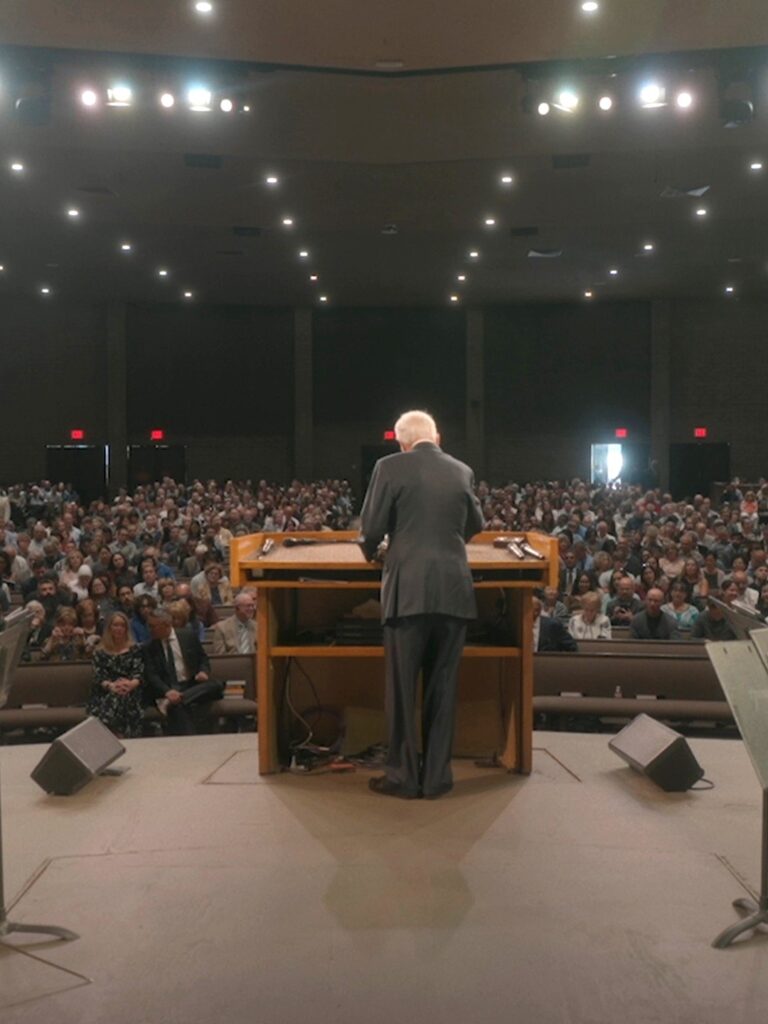

(Image from The Essential Church documentary)

We are now familiar with the images of the Capitol rioters on January 6, 2021, praying on the floor of the Senate, claiming the mantle of God’s approval for their insurrection. The entire violent episode was bathed in Christian imagery. As one banner proclaimed: “Trump is president, Christ is King.”

Yet some evangelical Christians had a trial run at defying the government the summer before January 6, during the height of the second wave of the Covid pandemic.

On July 13, 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom declared the closure of venues and sectors that “promote the mixing of populations beyond households.” These included indoor dining, movie theaters, gyms, salons, museums, malls, and places of worship. A short while later, the state issued more specific limits that restricted indoor attendance “to 25% of building capacity or a maximum of 100 attendees, whichever is lower.” Grace Community Church in Los Angeles, with an average weekend attendance near 3,000 people and led by Pastor John MacArthur—one of Donald Trump’s most vocal evangelical supporters—made headlines for their refusal to abide by California’s restrictions on large indoor gatherings.

On July 24, the elders of Grace Church published an essay in response to the July 13 order titled, “Christ, not Caesar, Is Head of the Church,” which presented their case for “the biblical mandate to gather for corporate worship.” Two days later, on July 26, they met for their Sunday service in defiance of the state mandate to remain closed. This action prompted a legal standoff between the church and L.A. County. The case for Grace Church did not seem strong. The same day the church’s elders published their essay, the U.S. Supreme Court issued their second ruling of the year denying a church’s request for religious exemption from a state’s public health restriction on religious services.

That all changed on September 18, 2020, with the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. With the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett, the Court began issuing a string of decisions against state health mandates, declaring that they violated the Free Exercise clause of the First Amendment. On February 5, 2021, the Court decided South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, which directly pertained to Grace Community Church. The decision enjoined the state of California from enforcing its protocols on places of worship—namely, limiting attendance to 25% of building capacity and placing bans on singing. On August 31 that year, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to settle with Grace. Both the county and the state paid the church $400,000.

From the perspective of political pundits and everyday observers, the legal battles involving Grace and other churches were a minor storyline compared to the scale of the crisis posed by Covid and the presidential election.

But things look starkly different from within the world of American evangelicalism. For communities like Grace, their legal victory over L.A. County and Governor Newsom was nothing less than a divine vindication of their fidelity to Christ. In their minds, they were on the front lines in the war against Satan.

***

For evangelicals like Pastor John MacArthur, the battle between good and evil is waged in small, seemingly insignificant moments. As depicted in the recent documentary, The Essential Church, currently available on several streaming services, the gathering of Grace’s elders on July 23, 2020, was one such moment.

The film, created by Grace Productions, the video production ministry of Grace Community Church, documents efforts made by Reverend MacArthur and the church’s elders to gather regularly for in-person worship in violation of public health measures. The film also profiles two other ministers, James Coates (pastor of GraceLife Church of Edmonton) and Tim Stephens (senior pastor of Fairview Baptist Church in Calgary), who faced legal consequences and brief imprisonment for their attempts to do the same in Canada. These stories appear alongside historical references to the Scottish Covenanters’ opposition to the forced use of the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer in the seventeenth century, weaving together a historically oriented thesis: “Satan has always used the power of governments to control the church. Nothing has changed, except his strategies.”

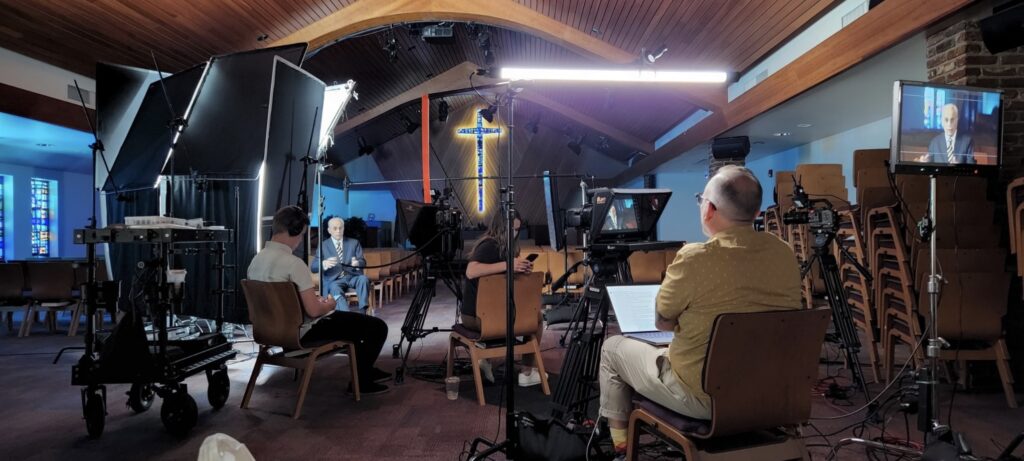

(Promotional material for The Essential Church)

In support of this thesis, the film highlights a key instigating moment for the Scottish Covenanters: when street vendor Jenny Geddes threw her stool at the Dean of St Giles Kirk in Edinburgh for reading out of the Anglican prayer book. The Scottish Covenanters resisted attempts to regulate worship by the King of England, Charles I—disputes that contributed to the First and Second English Civil Wars in the seventeenth century. The film plays up the fact that Geddes’s act of resistance occurred on July 23, 1637—the same date, separated by 383 years, as the gathering of Grace Church’s elders. The filmmakers are counting on viewers to see this as a sign of Satan’s repeated attacks on the church throughout history, as well as the enduring spiritual continuity of authentic Christians amidst oppression and persecution.

Watching this documentary will not give viewers an informed understanding of the legal and political conflicts of 2020 and 2021. The film almost completely ignores the details recounted above, such as the other churches who filed the original lawsuits and the importance of Justice Barrett’s appointment for the final outcome. The Essential Church, which so far has grossed over $400,000 according to IMDB, is not an educational film. It is a work of evangelical propaganda, a highly polished tract designed to convert viewers into cobelligerents.

Conversion is not too strong a word for it. In the final half-hour of the two-hour documentary, the interviewees—notably Ian Hamilton, president of Westminster Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Newcastle, England, Calvinist author and missionary Voddie T. Baucham, Jr. and MacArthur himself—begin preaching their understanding of the Christian gospel, according to the strict tenets of Calvinist doctrine. It is no accident that the beliefs of many Christian nationalists today are rooted in a narrow sectarian theology from the seventeenth century, which pictures God as absolutely sovereign over every domain, controlling every sphere of life in the fulfillment of God’s plan. For this reason, the filmmakers include explanations of several points of doctrine, including divine punishment, a hell of eternal conscious torment, and the authority of the Bible—all couched within the context of a cosmic war between Good and Evil. The film revels in the difficulty of their teachings, as if to show how seriously they take their faith in contrast to others.

These theological matters may seem obscure and disconnected from the topic of Covid health restrictions, but within the mindset of conservative American evangelicalism, everything is part of God’s grand strategy. What outsiders might see as conspiracy thinking is, for some evangelicals, simply a logical entailment of divine revelation.

***

The Essential Church places opposition to Covid-era mandates within an apocalyptic battle in which a righteous remnant of the ostensibly true church, as represented by Grace and the aforementioned Canadian pastors, has alone remained faithful to God, meaning that they see themselves as set apart from even other American evangelicals who adhered to government-issued orders against indoor worship.

For Grace, the application of public health measures to churches is an illegitimate government incursion into the life of the church. They believe their opposition to those ordinances is one of faithful Christians being sincerely obedient to Christ, who alone can be head of the church. The government should have no say in how Christians worship, and any attempt to do so reveals itself to be, according to Pastor Coates, the “spirit of Antichrist at work in the government.”

(Promotional material for The Essential Church)

It is worth noting that the “true church,” according to this film, is not just any church affected by Covid mandates or even any church that stands up to the government. The Essential Church is conspicuously uninterested in ecumenism. For the documentary’s creators, the true church requires true doctrine, hence the extensive discussion of Calvinist theology, as well as true practice, which in the documentary is limited to the practice of gathering weekly as a congregation to hear the preaching of the gospel.

For this reason, the documentary expresses no alliance or solidarity with the other churches involved in lawsuits against California, most of them Pentecostal, many with women in leadership roles. It matters not that they share a political agenda. Harvest Rock Church in nearby Pasadena is co-pastored by Ché Ahn (along with his wife Sue), a prominent member of the New Apostolic Reformation movement, who spoke at one of the “Stop the Steal” rallies shortly before the January 6 storming of the Capitol. You would never know from the film that Harvest Rock was one of the principal churches that sued California in the summer of 2020.

South Bay United Pentecostal Church in Chula Vista—which was involved in two Supreme Court decisions, one before Justice Barrett joined the Court and the other after—is particularly notable because they were represented by the same law firm as Grace Community Church: the Thomas More Society, a conservative Roman Catholic public interest firm, showing that they are not above ecumenical alliances when it supports their cause. Even though South Bay’s decision was the one that paved the way for Grace’s final settlement, and despite sharing legal representation, The Essential Church acts as if they were nearly nonexistent, or of very little importance.

The documentary instead features Coates and Stephens because they share the same theological views as MacArthur: Coates earned both his master’s and doctoral degrees from MacArthur’s The Master’s Seminary, while Stephens is currently working on his doctoral degree at Master’s. Solidarity presupposes doctrinal uniformity.

In this respect, the film is a throwback to 1920s Scopes Trial–era fundamentalism, when believing in the right doctrine was what mattered. But the prominent role of the Thomas More Society in the documentary is a sign that we are very much in the 2020s.

The Thomas More Society gained notoriety later in 2020 for its role in filing lawsuits in several states challenging the presidential election results. Jenna Ellis, a special counsel for the Thomas More Society, not only represented MacArthur’s church but subsequently served as the senior legal adviser for Trump’s effort to overturn the election. The Essential Church was released in theaters on July 28, 2023. On August 14, Ellis and 18 other people were indicted by a Fulton County, Georgia grand jury, and on August 23 Ellis turned herself in at the Fulton County jail.

Ellis is a major presence in the film and is one of the main talking heads regarding the legal details of the Grace Church case, but her connection to Trump casts the rest of the documentary in a different light. The Essential Church studiously avoids references to January 6, but the links are impossible to ignore.

***

Those profiled in the documentary appeal to “King Jesus” as the source and defender of their position. Heard against the backdrop of Scottish Covenanters’ opposition to the English crown, the language of “Christ as King” intentionally implies the illegitimacy of foreign power. Viewers are encouraged to draw the implications concerning state and federal governments in the United States. It becomes clear that while people within the documentary attempt to use the phrase to connote a sense that their faith is pure and apolitical, it is instead woven into the politics of the past and present. King Jesus here stands in opposition to CDC guidelines, as well as to the legitimacy of the 2020 election.

Another example of the film’s connection to today’s right-wing politics is found in the documentary’s discussion of public health. When profiling Deena Hinshaw, who served as Chief Medical Officer of Health for the province of Alberta, Canada, the film insinuates that her training in public health means that she is not a real medical expert. The filmmakers interview Baucham, the evangelical author and missionary, who dismisses public health as a “neo-Marxist” field of study, along with women’s studies, Black studies, queer studies, and cultural studies—all of which are seen as part of a cultural (and spiritual) revolution waged by the forces of evil. Baucham is well known for his attacks on critical race theory in his book, Fault Lines. He was the featured speaker at a Heritage Foundation event in 2021 on the topic. While he may not be interested in partnering with those outside of his narrow Christian circle, Baucham’s rhetoric is strikingly similar to that of Christopher Rufo, the right-wing activist who has targeted university leaders over their antiracist policies.

The Essential Church casts a group of sectarian Calvinists as warriors in a timeless spiritual battle against government, secularism, and Satan. In the film, MacArthur declares, “The church has become the main enemy of the government.” It’s an odd story at best, given that their victory is ultimately achieved by the same government institutions they claim are being used by the Antichrist. The narrative is riddled with contradictions and logical gaps.

Like any piece of propaganda, the documentarians’ message is based more on affect than reason. The film’s affect is one of conspiracist anxiety: the government is a Marxist cabal used by the Antichrist to persecute the truly faithful. The takeaway is that Christians must be prepared to resist the government—even to die trying. The film devotes several minutes to the Killing Time, when the Scottish Covenanters were executed for their rebellion. The filmmakers draw an explicit connection to the arrest of Pastors Coates and Stephens, comparing them not only to the Covenanters but also to John Bunyan, the persecuted Protestant writer who was arrested for preaching outside of a church in seventeenth-century England.

The film’s ultimate goal, and one that represents a broader trend within white American evangelicalism, is merely to confirm what its viewers likely already believe: if they feel “persecuted” for any reason, which now includes having to wear a mask, then they are authorized by God to resist.

The film closes by reminding viewers that what U.S. state and federal governments did during Covid amounted to a “battle against God.” It is a call to discern Satan’s shifting tactics within the state and to make a stand in public opposition.

In the case of these three churches, that meant attending Sunday worship against government orders. But on January 6, 2021, some took that lesson to mean storming the United States Capitol.

We do not know exactly what King Jesus’ vigilant defenders might see next, but it is clear that they are looking.

David Congdon is Senior Editor at the University Press of Kansas. He is the author most recently of Who Is a True Christian? Contesting Religious Identity in American Culture (Cambridge, 2024).

Jason Bruner is Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University. He is author of Imagining Persecution: Why American Christians Believe There is a Global War against Their Faith (Rutgers, 2021) and co-editor of Global Visions of Violence: Agency and Persecution in World Christianity (Rutgers, 2022).