Evangelical Women Leaders as LGBTQ Allies

The ramifications of evangelical women leaders publicly supporting LGBTQ Christians

(Image by Temi Oyelola)

When I was getting ready to graduate from high school, my parents gave me a ring with a beautiful pearl to wear on my left hand. They said it was important to “promise yourself to God,” and “be pure and holy,” clearly anxious about me leaving for college and what happens to many hormonal teenagers when they are crammed together in a small space. The moment wasn’t overtly ceremonial, but it stayed with me, even after I failed to keep the promise my first year in college. I kept the ring, but I never wore it.

My immigrant Korean parents were not technically evangelical, but our Protestant church mirrored the evangelical culture that surrounded us in Colorado Springs. The ring they gave me was an expression of both American evangelicalism and a purity culture that dictates the rules around gender and sex, a way of seeing the world that permeates the air, like a region’s climate — we breathe it, we consume it, and it dictates how we live and whose lives are worthy. In college, I joined several evangelical Christian groups even as I attended a less conservative local Presbyterian church. Each group had its own flavor, but they all touted similar ideas about sexual behavior: we must remain abstinent until marriage to stay pure.

But I began to see how purity wasn’t only about virginity. It was also about gender — men being “men” and women being “women,” with certain masculinities and femininities lifted up, each undergirding particular roles. Other sexual identities or orientations were not part of the equation because it was so far out of the realm of social or moral possibility. Although some Christian groups were more explicit in their teachings on the sin of homosexuality, others tried to soften the blow with a cliché of dubious origins that I eventually internalized: “Love the sinner, hate the sin.”

“Love the sinner, hate the sin” became a kind of mantra at the center of evangelical organizations when dealing with the “problem of homosexuality” as a deviant form of sexual behavior. The phrase addressed all manner of sins – gambling, lying, cheating – and emphasized that, like any other sin, homosexuality was simply a behavior that could be eliminated with intention and effort. But homosexuality, they warned, was a particularly pernicious sin and required special attention. Eternal salvation, as Sara Moslener explores in her book Virgin Nation, was tied to a person’s sexuality

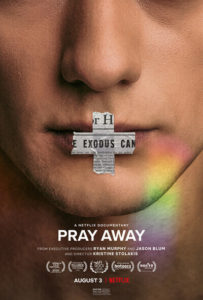

The recently released Netflix documentary Pray Away shows us the violent consequences of this “love the sinner, hate the sin” perspective, and the years of trauma induced by people who insisted that one could literally “pray away the gay.” As the documentary highlights, evangelicals embraced conversion therapy — a “gay-cure therapy” that uses talk therapy and negative reinforcements to remove a person’s feelings of same-sex attraction and, hopefully, to force an attraction to the opposite sex. For transgender evangelicals, the goal of conversion therapy was to help people identify with their assigned birth sex.

Pray Away focuses on several former leaders of Exodus International, the once-largest ex-gay organization in the world. Julie Rodgers, one such leader, left the organization after recognizing the harm it caused so many people, including herself. She explains that she initially had a happy childhood. “I wanted to be good,” she said. But the messages about sexuality started early. “Everything in our life was conservative Christianity…My mom listened to all of [the main leaders] on the radio…the main messages I heard were ‘gays are really, really bad’—dirty, scary, bad.”

Pray Away focuses on several former leaders of Exodus International, the once-largest ex-gay organization in the world. Julie Rodgers, one such leader, left the organization after recognizing the harm it caused so many people, including herself. She explains that she initially had a happy childhood. “I wanted to be good,” she said. But the messages about sexuality started early. “Everything in our life was conservative Christianity…My mom listened to all of [the main leaders] on the radio…the main messages I heard were ‘gays are really, really bad’—dirty, scary, bad.”

Interspersed with Rodgers’ story, the documentary cuts to clips of Focus on the Family founder James Dobson and evangelical leader Jerry Falwell speaking saying, “There’s a secular agenda and it’s coming for your kids…Homosexuality is moral perversion and always wrong. Period. Every scriptural statement on the subject is a statement of condemnation.”

Even as Rodgers struggled with same-sex attraction, she remained convinced that, “God would help me to lead a life of purity and holiness.” For evangelicals, purity is not simply about virginity; it is about upholding heterosexuality. Everything else is not only sinful, but a ticket straight to hell.

In 2012 then-president of Exodus International Alan Chambers renounced conversion therapy, and the following year, he closed the organization and apologized for the “pain and hurt” participants of their programs had experienced. This was a major rupture in the American evangelical world. It compounded the unraveling of a once-solid worldview for evangelicals. Many entered into a process called “deconstruction,” a re-examination of their faith that led them either to leave Christianity completely or to join more progressive Christian communities.

Other events in the last decade contributed to more evangelicals leaving the faith, including the election of Donald Trump, the #ChurchToo movement, which, building on the #MeToo movement, focused on the sexual abuse of minors and women by church leaders (both of these are indebted to sexual harassment survivor and activist Tarana Burke who coined the phrase #MeToo in 2006 and inspired #ChurchToo). All of this produced a kind of reckoning for many evangelicals to reflect on their participation in a tradition that was the cause of much harm and violence, especially toward LGBTQ people and people of color.

Evangelical Women Leaders Becoming LGBTQ Allies

As the reckoning unfolded, some evangelicals started to question the systems of purity that undergirded their “love the sinner, hate the sin” faith. A few evangelical leaders began to speak out – mostly women. Some are ordained clergy, while others have large platforms and substantial audiences of evangelicals who trust their perspectives on marriage, family, and faith. They became public allies for the LGBTQ community, a move that is changing the landscape of American Christianity even as these women have faced financial and professional backlash for their decisions.

One prominent evangelical ally is the highly sought out speaker, writer, and HGTV star, Jen Hatmaker. She came out in support of gay marriage and the inclusion of LGBTQ Christians in evangelical churches in the fall of 2016. She said in an interview, “From a civil rights and civil liberties side and from just a human being side, any two adults have the right to choose who they want to love. And they should be afforded the same legal protections as any of us. I would never wish anything less for my gay friends.” While she emphasized civil rights, Hatmaker had a theological basis for her allyship too, saying, “Not only are these our neighbors and friends, but they are brothers and sisters in Christ. They are adopted into the same family as the rest of us, and the church hasn’t treated the LGBT community like family. We have to do better.”

Hatmaker’s support for the LGBTQ community had immediate consequences. LifeWay Christian Stores, the large Southern Baptist bookseller that published Hatmaker’s 2012 bestseller 7: An Experimental Mutiny Against Excess discontinued the sale of her books. In the evangelical world, this was not only a financial repercussion, but also a flat-out rejection of her as a respected Christian voice from an important evangelical institution.

Other evangelical women leaders came out in solidarity with Hatmaker, including Sarah Bessey, author of Jesus Feminist, Out of Sorts. Bessey, who first emerged during the Christian “Mommy Blogger” phenomenon that started around 2010, wrote a blog entry in support of Hatmaker‘s views. She said, “As someone that is a heterosexual evangelical Christian herself, I think that same-sex marriage should be legal — and I think that Christians, even those that believe homosexuality to be a sin, need to back off the issue.”

Like Hatmaker, Bessey emphasized civil rights. But she took things a step further by asserting her theological convictions: “The point of God, the point of Jesus, the point of the Holy Spirit is not to block same-sex legislation. The point of Christianity is not to create a theocratic Christian society. No one is won to Love by hate or legislation.”

(Christian event with Sarah Bessy on LGBTQ allyship)

In 2019, Bessey announced that she and her family were leaving their local church and no longer connected to one of the largest global evangelical networks, Vineyard Canada, explaining that they made the decision because of differences with the organization on LGBTQ inclusivity. Bessey writes, “GLBTQ disciples are among us — and always have been — as a faithful witness to the resurrection of Jesus Christ. They are the church just as much as the rest of us, each deeply beloved by God and by their community.”

Today, Bessey is co-leader of Evolving Faith, an LGBTQ affirming gathering that makes space for Christians to question what they were taught about sexuality. “It exists to cultivate love and hope in the wilderness, pointing fellow wanderers and misfits to God as we embody resurrection for the sake of the world,” she said. Every year, Evolving Faith brings together thousands of Christians for its conferences and remains a major network for ex-evangelicals and other Christians.

Another high-profile evangelical LGBTQ ally is the Korean-American minister, Reverend Gail Song Bantum, the lead pastor of one of the largest multiethnic evangelical churches in the United States. She explained to me that she did not have a public “coming out” moment as an ally, saying, “I’m someone who names things as I grow and evolve and when the opportunity presents itself. I name what I don’t know, but I also name my convictions. I’ve never really carried things in my lifetime that required a big reveal … you just get what you see.” But she eventually had to clarify her position about LGBTQ Christians when her church put her up for consideration as the next senior pastor of her congregation. Her announcement that she viewed LGBTQ Christians as equal in God’s eyes became a major point of contention for the community. But she insisted she had to be transparent in order to be a different kind of leader for the church. “I’m not about bait and switch,” she said. “I’m also not desperate for power. I’m also not going to lead a church if I can’t operate with full integrity of conviction and action, with authenticity and transparency.”

The stakes are high for women clergy such as Song Bantum who work in denominations like the Evangelical Covenant Church that do not welcome LGBTQ Christians. But Song Bantum believes this is one way to enact change and enable inclusion of LGBTQ people. Such a position is risky because churches can be ejected from denominational membership and clergy can be stripped of their credentials, which is something Song Bantum currently faces. She posted on Instagram, “This time next year, I will most likely have my ordination credentials revoked and our beloved church removed from the denomination we belong to. I do not take the story of our church, the many relationships that have been fostered, the historic nature of my ordination as a Korean American woman and the multiracial church I have the privilege of leading lightly.”

Another prominent evangelical, and New York Times bestselling author, Rachel Held Evans became a public ally for LGBTQ people. She began to question much about her faith on her blog, especially around social justice issues. In 2014 Held Evans led a multi-week “book study” on her blog on Matthew Vines’ God and the Gay Christian, a popular book about what it means to reconcile Christianity and LGBTQ identities. In 2016 she wrote a post that outlined her own journey and clear pro-LGBTQ position. It was eventually published posthumously by her husband, Dan Evans. She announced, “I affirm LGBTQ people because they are human beings, created in the image of God. I affirm their sexual orientations and gender identities because they reflect the diversity of God’s good creation, where little fits into rigid binary categories. They are beloved children of God, just as God made you.”

One other notable evangelical ally is Cindy Wang Brandt. She developed a large following through her blog and social media where she was an outspoken advocate for the LGBTQ community. She says, “Although I was raised a conservative evangelical Christian and was taught traditional views of marriage, my brother came out as trans in 2008. This, as well as public Christian discourse on this issue over the past decade, threw me on the same trajectory as many of the prominent evangelical Christians who have changed their minds.” But the evangelical school where she worked forced her to change her public positions on LGBTQ issues or quit her job. She resigned.

After Wang Brandt quit her job, she spent her extra time writing. She began to invite other parents like herself to join her. All of them were LGBTQ allies, LGBTQ themselves, or parents of gay and transgender children. She eventually created a parenting network and compiled resources for people who want to leave the world of purity culture and “family values.”

Although she faced significant consequences for her allyship, she views it with gratitude, saying “By far the biggest gift I have received by being publicly gay-affirming has been to become a refuge for LGBTQ people, and especially Christians, who consider me a safe person with whom to share their lives.”

***

The presence of LGBTQ people in evangelical communities is undeniable. In 2016, Julie Rodgers shared a story: in 2014 she was surprisingly appointed as the first gay chaplain for Wheaton College, a major evangelical Christian institution. She had hoped this was a sign of meaningful change in the evangelical world. She even signed a pledge to commit to celibacy so that she did not violate the school’s expectations to reserve sex for heterosexual marriage. But the more conversations she had with the administration the more she realized she couldn’t fully be herself in that position, especially when the administration asked her to stop referring to herself as gay. Rodgers resigned a year later, saying, “My experience with the administration confirmed a quiet concern that had grown for years: that traditional views of marriage were often rooted in something other than sincere Christian convictions. If they couldn’t support someone committed to celibacy — someone who abided by their Community Covenant alongside every straight employee — I could only conclude that their anxiety wasn’t about my sex life. Their anxiety was about my existence.”

Following her resignation, many Christians, both LGBTQ and allies, came out in support of not only her existence, but her voice, perspective, and leadership. Eventually she shared her story in her memoir Outlove: A Queer Christian Survival Story. Rodgers continues to speak, write, and teach to evangelical and broader Christian communities.

***

The shift each of these women made to move away from purity culture to affirm LGBTQ people caused shockwaves throughout evangelical Christian communities where many viewed it as a kind of betrayal. But these women leaders have offered a much more expansive view of Christianity. And so we are beginning to see their impact on institutions in helping to change what inclusion looks like in issues ranging from leadership to marriage to family. They are providing space for support and affirmation through the online communities they have developed, conferences they have organized, and they support groups they have sponsored. Slowly, we are seeing how these women are changing the landscape of American Christianity. Hopefully more male evangelical leaders will follow in their footsteps and step our meaningfully as LGBTQ allies soon.

***

I still have the ring my parents gave me – a reminder of the beliefs and stories that helped my family make sense of everything at the time. Might makes right. God helps those who help themselves. Love the sinner, hate the sin. Purity is everything. My parents were first-generation immigrants from a country that was heavily influenced by evangelical American Christianity, and we imbibed these notions as though they were sacraments necessary for our salvation.

I am now an ordained minister in a fairly progressive mainline denomination. And I’m a queer woman of color who is married to a straight man. I can relate to what it takes to let go of deeply held beliefs. I also acknowledge that the stories of these evangelical women leaders are not without flaws and complications. We need to keep pushing the boundaries of “inclusion” because there are still questions about how far their inclusion extends as some of them hold to or remain in traditions that only recognize monogamy as the legitimate form of intimacy — one has gone so far as to publicly affirm it. There is also a continuous need to consider the intersecting vectors of identity that are often overlooked in these conversations — not only gender and sexuality, but race, ability, immigration status, and economic status. But these women are not the only voices, and they are modeling a way to initiate leadership and change by amplifying others. There are so many stories out there, moving the needle within institutions and families, embodying alternative possibilities, and fostering wider, fuller possibilities for queer Christians in America.

Mihee Kim-Kort is a Ph.D. candidate in Religious Studies at Indiana University.