Epidemic Empire: A Conversation with Anjuli Raza Kolb

Contributing Editor Kali Handelman interviews Anjuli Raza Kolb about her upcoming book Epidemic Empire and its connections to today.

As the coronavirus began to take hold of our lives, our news, and became our undeniable, global, shared reality, I kept thinking about Anjuli Raza Kolb’s upcoming book, Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror, 1817-2020. Raza Kolb’s book examines the metaphoric, literary, historical, and political relationships between terrorism and disease by tracing the trope of invasive, contagious violence from colonized India to post-9/11 America. Raza Kolb was generous enough to discuss her work with me in an extended conversation conducted primarily via email over the course of the last month.

***

Kali Handelman: It’s pretty common that published conversations like this take place at a distance, but the coordinates of our respective locations seem particularly poignant right now because, in a strange convergence of coincidences, I am writing to you from London, just a few miles from where the Epidemiological Society of London once convened, not too far from the statue of John Snow’s Broad Street Pump, and also pretty close to Imperial College, which produced the study that many credit with having finally turned the tide toward more extreme measures to protect the public from the coronavirus pandemic in the US and UK. And, even more coincidentally, you are multiple time-zones away from me, but only a few miles from where I grew up, which is, infuriatingly, not far from where one of the first American cases of coronavirus made the news back in early March.

It’s not all serendipity that has brought us “together,” of course. I am surely not even close to the first person to remark on the uncanny prescience and relevance of your work. But that prescience is, of course, not a coincidence, and I wanted to speak with you so that you could help us think through our current moment and — importantly — its history, using what you have learned and the critical lens you are developing.

So, I am hoping that first you can give us a quick introduction to your research subject. The project, of course, predates coronavirus, as it also predates Trump’s election and all of the calamities that have occurred since. How did you first come to this particular study and its convergence of topics?

Anjuli Raza Kolb: In the broadest possible terms, my research subject is colonial science and postcolonial poetics. My book is about how the “epidemic of terrorism” became a kind of common sense after September 11— so much so that I don’t think most people would even think of epidemic here as a metaphor! As an American Muslim, however, the language rang really discordantly for me right from the start. As I began a serious study of colonialism and postcolonial literature, I kept coming back to the many ways the War on Terror looked like a colonial war, and I set out to understand why the epidemic metaphor became such an easy and ready way to talk about relatively isolated acts of violence outside the legal framework of state-on-state violence. What I discovered is that anti-colonial insurgency in India — Britain’s largest and most lucrative colony in the age of high imperialism — was persistently tethered to both the cholera epidemics (which were frequently imagined as purposive violence against British troops or simply “revenge”) and also Muslim “fanaticism.”

“Love in the Time of Corona” in Times Square

It hardly bears repeating here that far before the cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century, European literature, history, and medicine were fond of linking diseases and pestilences to the East and what we now call the global South. I couldn’t compass this whole history in a single book, and many other better scholars (Hans Zinnser is one I particularly adore) have written about these issues in ways I’ve tried to honor and build upon. In a way this was lucky for me, though, because it helped me to focus and see how Islam in particular has been on the receiving end of a really persistent and patterned version of this pathogenic xenophobia in ways that truly have gotten worse over time, not better. I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say that the hatred and fear of Muslims has been the most persistent driver of U.S. foreign policy for the better part of two decades, while anti-Black hatred drives most of our domestic or internal colonial “wars.” With regard to Trump and the coronavirus pandemic—of course I didn’t know of these eventualities when I started researching this book. I will say, however, that the longer you immerse yourself in materials like these, the less shocking these outcomes appear.

KH: Right, that’s a really useful way of thinking about what I was calling “coincidence.” It’s a trained practice of immersion and interpretation. And, in fact, one of the main things I wanted to ask you about was the method of interpretation you developed for thinking about the relationships — historical, political, ideological, literary, discursive — between epidemics and (what is called) terrorism. You do the work of both naming your subject “the epidemic imaginary” and calling for and modeling a method of interpreting epidemiological texts using an “epidemiological mode of reading.” Can you please explain what “the epidemic imaginary” is and about what it means to read epidemiologically?

ARK: You’ve made the work sound smarter than it is here! Let me start by naming what I mean by epidemiology, which is emphatically not a technical or useful definition for practicing epidemiologists. What I mean is the establishment of a self-conscious and institutionalized (societies, journals, meetings) discipline called “epidemiology” in the late-nineteenth century in Britain and France founded in response to the cholera epidemics. Because the discipline was formed in this moment, we have to take seriously that it is a field of study inseparable from the management of empire.

In the writings of early epidemiologists, we can observe a few habits that are salient to the questions I try to pursue: an interest in weather, climate, topography, and ethnic “character;” a style of writing normally seen in colonial travelogues (a lot of personal reflection and description); a heavy borrowing from sensationalist, Gothic, and Orientalist tales; and a synoptic or multi-vocal perspective that posits, or maybe even theorizes, the dispersed nature of epidemic events as requiring synthesis, collation, and interpretation. This last feature — dispersal and the necessity of synthesizing — also produces some consistent metaphorical operations. The most crucial of these is the way epidemiologists imagine the social body as isomorphic with the human body.

Anatomists and pathologists, who shaped Enlightenment medicine, (to borrow Foucault’s important periodization from The Birth of the Clinic) didn’t really consider the health of the social whole — their methods were more focused on the appearances and sensible changes in body tissues. Clinical practice was different from the study of epidemics, which really took off in the middle of the nineteenth century. Think of the difference, for example, between the optic of a surgeon and that of a diarrheal specialist — the latter needs to know so much about farming, water filtration, sewage systems, routes of travel, and so forth, while the surgeon is responsible for solving the local (proximate) problem that may be the consequence of more global (distal) factors. If the epidemic imaginary metaphorizes the social body as a singular body, as it often does, it faces challenges in scalar translation and interpretation. So an epidemiological reading method is one that attends to both the digestive system of the patient and to the digestive system of the town, region, nation, or globe.

I’m trying to be brief, so this is a little loose. Because I am a literature specialist, I have found it productive to think of the distinction between the gaze of the clinic and the view of epidemiology as akin to the difference between close reading on the one hand and literary history or other comparative and synthetic reading practices on the other. If studying historical epidemiology taught me something about my own methods, it’s that postcolonial criticism tends to work similarly, as a mixture of very tight close reading, constellated juxtapositions (this is like anecdotal data in studies of epidemics), and rangy, systemic thinking. This was a tricky discovery to make because, as you may guess, one doesn’t want to find that one is working in a similar mode to a science that was founded to maintain the economic superiority of the colonial centers, and to oppress and abandon one’s ancestors to the ravages of undernourishment, overwork, and disease.

KH: No, I can definitely see that! But, as you said, you’re a literary specialist and, in your work, you primarily focus on interpreting 19th and 20th century literary texts — from Mary Shelley to Salman Rushdie. You also read Supreme Court decisions and state department publications, though. Which makes me wonder, what are you reading right now? And what does — or would — it mean to read news and commentary “epidemiologically”?

ARK: I am aggressively reading the news! As I think we all are! To your second question, what would it mean to read our contemporary media landscape epidemiologically, I’ll try to give a pared-down answer first, and then a more citational one.

First, there are so many reasons to separate literature from normal or popular discourse, but I think there are more reasons not to. So I always try to look at the pathways along which these genres of writing and speech move, permeate, and inflect one another. Simply put: I think reading epidemiologically means reading to solve a problem that is a threat to collective wellbeing. I’m not equipped to have anything useful to say medically — so what I mean by problem is not the virus itself, but rather the hideous racism and xenophobia we’ve seen in the West in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

I’m interested in how mainstream popular literature becomes a kind of hearth around which we gather in these times. So many people, for example, are reading Camus’ The Plague right now — an insanely problematic text that I’ve tried really hard to understand as a “great novel” (I don’t think it’s that great) and also, now, as a feature of our daily news cycle. We have to read the spaces between the two categories. To do this I find myself asking: what are the habits of mind and speech doing harm? How does Camus’ formulation migrate to White House speech writers? How, then, does Trump reorganize this into the hateful discourse that reappears in the mouths and tweets of “minor players”? How have colonized subjects, and now Asian Americans, been forced to weather this storm? How have already abused and marginalized communities suffered not just disproportionately but criminally as a result of the long term and renewed withdrawal of care and social services that is the hallmark of settler colonialism?

To bring things closer to the present, how have incarcerated, unsheltered, and precariously housed people faced levels of danger and harm that are nothing less than immoral? At the same time as we have to continue to do the work and undertake the activism that addresses the blazing inequalities in North American society, we must also be attuned to the rhetoric that normalizes these abuses and perpetuates them in the name of “classical” or American values. Reading this way is a process of compiling data of minor linguistic, behavioral, and discursive racism during a time of heightened ethno-nationalism. Cathy Park Hong (a poet) has published a wonderful essay doing exactly this with regard to the surge of racism against Asian Americans in the last months, as has Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (a scholar) on the long history of anti-Black racism and the current morbidity outcomes of COVID-19. If we agree with the theorists who define disease as a set of biological phenomena responding to social processes[1] (and I do), we have to believe that our actions determine the course of pandemic and define the disease. Action here includes language.

My more citational answer is that reading epidemiologically (this is a quality of practice, not a technical definition!) in the midst of an epidemic also means letting go of the pressure to create new paradigms and theories, new methods and lenses — and instead to strategically pluck what is most useful and most tactical. So thinking with Eve Sedgwick, I’d ask: can we read symptomatically without paranoia? In the very first weeks of the Wuhan outbreak, I picked up Ling Ma’s Severance. A friend left it at my place over winter break. As a kind of object lesson in paranoid vs. rangy epidemic reading: I didn’t know that it was about disease and late capitalism. One lonely day I thought — I need a fun novel to lift my spirits, maybe this pink book is right! After ten pages, I realized this was no random “Oh, thanks for letting me stay in your apartment” gift. My friend gave it to me because it was about everything I care about and study: race, waste, ennui, fevers, cults, suburbia, apocalypse.

My more citational answer is that reading epidemiologically (this is a quality of practice, not a technical definition!) in the midst of an epidemic also means letting go of the pressure to create new paradigms and theories, new methods and lenses — and instead to strategically pluck what is most useful and most tactical. So thinking with Eve Sedgwick, I’d ask: can we read symptomatically without paranoia? In the very first weeks of the Wuhan outbreak, I picked up Ling Ma’s Severance. A friend left it at my place over winter break. As a kind of object lesson in paranoid vs. rangy epidemic reading: I didn’t know that it was about disease and late capitalism. One lonely day I thought — I need a fun novel to lift my spirits, maybe this pink book is right! After ten pages, I realized this was no random “Oh, thanks for letting me stay in your apartment” gift. My friend gave it to me because it was about everything I care about and study: race, waste, ennui, fevers, cults, suburbia, apocalypse.

A paranoid approach to this happenstance might linger with the psycho-social (why did she leave me this book, what’s she trying to tell me about my career, my nation, my personhood?) or with the socio-psychic (oh no, there’s a deeper, different message here, the story about the fevered is actually about reproduction, the plot about bibles is secretly about cults). With this canny book in particular, all those things are there, and none of them are. Ma is so sharp about how we talk about those things, what the news sounds and looks like during a crisis. So I am trying to read with her. Reading symptomatically without paranoia means taking the literary epidemic at face value (it’s not trying to teach us that God hates us, it’s not a fucking metaphor), and to think about how a genre like speculative fiction is just straight up made from language and narrative patterns that reflect the actual events at our doorstep. Literature, in this mode, is not a “what if this insane thing happened,” but a “what if we could see more clearly what already is happening.”

To return to the practical — what I want is for the people who care to pay attention to the literariness of our moment, to poetic device, to the analogies our leaders make between political and “natural” phenomena. I have my own sense of how these work, but this is a project that cannot have too many analysts: I want everyone to have a strong opinion on what it means when Andrew Cuomo says the pandemic is just like 9/11. In my view, naturalizing metaphors almost always depoliticize. In the case of Cuomo’s 9/11-coronavirus analogy, he says the likeness is because they’re both “random.” When we ascribe randomness or non-human agency to events like this, it’s so easy to ignore the ways our political and economic systems have set up and maintained inequality, and how this inequality plays out in a raced, gendered, and classed calculus of harm and death. A sense of “randomness” also maintains heightened panic, which feeds a 24-hour news cycle, incessant surveillance culture, racist policing, borderline fascism, and insane spending on the military. Invoking 9/11 makes great soundbites for a politician in a crisis, but despite the amazing corps of medical workers flooding into New York from around the country to help, we know more (voting) Americans (including members of my own extended family) don’t really care about the residents of New York. They only care about the stories of American exceptionalism the tragedy of 9/11 enables.

To return to the practical — what I want is for the people who care to pay attention to the literariness of our moment, to poetic device, to the analogies our leaders make between political and “natural” phenomena. I have my own sense of how these work, but this is a project that cannot have too many analysts: I want everyone to have a strong opinion on what it means when Andrew Cuomo says the pandemic is just like 9/11. In my view, naturalizing metaphors almost always depoliticize. In the case of Cuomo’s 9/11-coronavirus analogy, he says the likeness is because they’re both “random.” When we ascribe randomness or non-human agency to events like this, it’s so easy to ignore the ways our political and economic systems have set up and maintained inequality, and how this inequality plays out in a raced, gendered, and classed calculus of harm and death. A sense of “randomness” also maintains heightened panic, which feeds a 24-hour news cycle, incessant surveillance culture, racist policing, borderline fascism, and insane spending on the military. Invoking 9/11 makes great soundbites for a politician in a crisis, but despite the amazing corps of medical workers flooding into New York from around the country to help, we know more (voting) Americans (including members of my own extended family) don’t really care about the residents of New York. They only care about the stories of American exceptionalism the tragedy of 9/11 enables.

KH: Which brings me to a question about media itself. In your book you talk about “the efflorescence of the terrorism plot in literature, television, and film.” I wondered about this word, “efflorescence,” which you use pretty often. It’s an interesting sort of biological metaphor in and of itself, and to me, it reads as almost mystical, and maybe even a bit passive. I wondered, though, if we could think more about how epidemiological discourse — such as the terrorism plot itself — “spreads”? What does it mean when we talk about a trend or a trope “catching on” (nevermind “going viral”)? What kind of agency do we see at work?

ARK: You’ve hit on something so important here — it’s incredibly hard to stay away from biological metaphors and the passivity they imply! I won’t make too much of it, because frankly you raise a good critique of my own writing habits, and I want to give it due respect. At the same time, if we want to linger with the metaphor, the etymology of efflorescence links it to plants in bloom, and as even a hobbyist plant lover knows, this can take some coaxing.

With regard to the question of agency, efflorescence “takes place” and is kind of passive, but it can also be enjoined to occur or continue when conditions are made favorable. I think the ground was made fertile for the terrorism plot in literature and film by a president, George W. Bush, who imagined and staged himself like a hero in a thriller. The consequence, culturally, was that it paid to write a sensationalist terror plot. Once a network picks up a show like 24 or Homeland, and the ratings skyrocket in a climate of fear stoked by warmongering leaders, a structure of incentives is installed.

You’re right that “spread” makes us think cultural phenomena like this are passively moving through our minds and laptops. I dispute this vigorously. These stories are opportunistically reproduced by studios, publishing houses, universities, and distributors because they make money. My own career is subject to this kind of critique: I have received fellowships because I work on terrorism and Islam — these resources were made rapidly available after the start of the War on Terror by the State Department and the many educational institutions that are supported by federal funding. A graduate fellowship I was offered (and declined) was funded by the Critical Languages Program. To my dismay, I learned this did not mean languages with a robust tradition of literary criticism, but rather languages critical to national security. The way the culture industry makes money is linked to the incentive to continue the scandalous spending on the military, paramilitary, intelligence services, police forces, and arms manufacturers. The floral metaphor begins to look entirely inappropriate when we dig into the analysis. I am sorry for using it, and sorry to drag plants into this mess!

KH: As you have so thoughtfully demonstrated here, metaphors and questions about what metaphors do are obviously central to your work. In your book, you write about how epidemiological thinking takes a social metaphor, “routes” it through biological and medical thinking, and then re-applies it to the social. A genealogical summary I found incredibly helpful. A recent article in the New Yorker by Paul Elie called “(Against) Coronavirus as Metaphor” draws on Susan Sontag’s seminal work[2] to argue that we need to shift away from the metaphors of virality and speak “literally” about our present moment if we are to have any hope of approaching and understanding it “clearly.” I have to say, it struck me as somewhat ironic that he leaned so heavily on the idea of “literal” language here, as though the colloquial “literally” isn’t one of our most overused examples of figurative speech. But that point aside, what do you make of Elie’s argument given your own thinking about what you call “the metonymic relation between a Western idea of Islam and the terror of a global epidemic.”

ARK: Elie is writing against this stubborn, faux-profound custom, returning, as so many of us have done, to Sontag. Elie explains, “Sontag’s work suggests that metaphors of illness are malign in a double way: they cast opprobrium on sick people and they hinder the rational scientific apprehension that is needed to contain disease and provide care for people.” Speaking in his conclusion of this “hindrance,” Elie points out what is to me the most important insight these early days of COVID-19 have brought, namely that

[O]ur disinclination to see viruses as literal may have kept us from insisting on and observing the standards and practices that would prevent their spread. Enthralled with virus as metaphor and the terms associated with it—spread, growth, reach, connectedness—we ceased to be vigilant. Jetting around the world, we stopped washing our hands.

I agree with the first part of Elie’s claim, but taking a slightly broader view — one that includes the history of the terrorism-as-epidemic metaphor and its future ramifications — I would go farther. This metaphor didn’t just keep us, passively, from observing the practices and standards that would prevent a pandemic; it pointedly suppressed these priorities and concerns by activating the belief that the immense wealth of the new imperium would by some trickle-down method keep “us” safe from the diseases afflicting the poor, the brown and black, the hungry, and the weak.

The lethal machinations of capitalism and liberalism are everywhere tied to racial and religious persecution. These systems are particularly and purposively bad at keeping people alive and healthy, let alone thriving. The withdrawal of communal care (including access to clean water, basic healthcare, and adequate housing) that results in maintaining racial and religious others on the brink of death, in states of profound precarity, is foundational to neoimperial sovereignty, even as neoimperial politics wax ethno-nationalist. This is partly what Achille Mbembe had in mind when he revisited Foucault’s important studies of biopolitics from below and outside, broadening the historical geography of Foucault’s theory of biopolitics to coin the term “necropolitics.”

Mbembe’s necropolitics attempts to “account for the contemporary ways in which the political, under the guise of war, of resistance, or of the fight against terror, makes the murder of the enemy its primary and absolute objective.[3] From rising hate crimes against Asian Americans and immigrants to the criminal abandonment of nearly everyone in America outside of the white, property-owning classes, we are seeing Mbembe’s principle at work daily, before and during the pandemic as surely as we will after. How does the War on Terror intersect with what very quickly became known as the War on the Virus? Does it matter that nearly all of these terms operate metaphorically, and that we nevertheless suffer concrete and irrevocable material harm because of them?

Mbembe’s necropolitics attempts to “account for the contemporary ways in which the political, under the guise of war, of resistance, or of the fight against terror, makes the murder of the enemy its primary and absolute objective.[3] From rising hate crimes against Asian Americans and immigrants to the criminal abandonment of nearly everyone in America outside of the white, property-owning classes, we are seeing Mbembe’s principle at work daily, before and during the pandemic as surely as we will after. How does the War on Terror intersect with what very quickly became known as the War on the Virus? Does it matter that nearly all of these terms operate metaphorically, and that we nevertheless suffer concrete and irrevocable material harm because of them?

KH: I wonder how we can think about these metaphoric failures together with what you’ve said about the epidemiological imagining of the body politic (that is, perhaps one could say, the “public” in “public health ) as isomorphic with the world at large. Because, of course, as you explain, we don’t all imagine ourselves as one united global body, we divide and exclude and draw boundaries along lines of race, gender, class, religion, etc. Which means that the people excluded from “the body politic” of the hegemonic power are dehumanized, and are, in your words, rendered “distinctly at odds with the human” by “the rhetorical effects of imperial disease poetics.” Or, more bluntly to the point, you write simply: “In this scheme, terrorists become subhuman—microbial, cancerous, viral.” How do you see that kind of dehumanization playing out now?

ARK: I’ve been returning to this — one of the earliest snarls I was trying to sort out while writing the book — a lot lately. We are seeing the dehumanization of East Asian people (by accident) and Chinese people (on purpose) play out in many of the same ways as we have seen the dehumanization of black Americans, Caribbean people, and Central and South Americans for centuries, in many of the same ways we have seen indigenous people and Muslims from all around the world — particularly the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa — dehumanized and likened to diseases and contagions, swarms and plagues, in pointed moments of political strife, for centuries. It is no mistake that this vilification is pointed at those who do our dirty work, make our goods, suffer labor conditions fully enfranchised Americans would never accept. It is so easy to paint workers as filthy, guilty, ignorant. Take, just for a small example, the uncensored reflexes of disgust that Western commentators avow when they describe the “teeming cities” and “wet markets” in China, as if global agribusiness and catastrophic monocultures have contributed nothing to the evolution of zoonotic viruses.

This is so depressing it’s hardly worth saying: global capitalism, driven by finance centers in New York and London will come up with any excuse to blame its others for anything it can, anything that will support the perpetuation of profit. It’s a nightmare that the same people who for years have demonized the notion of “martyrdom” as a Muslim pathology are now calling for people to sacrifice themselves to re-open the economy.

To understand how this metaphor keeps on working, despite changes in our conception of the body and the shape of geopolitics, we have to understand what Western — largely English — philosophy has bequeathed to us from Hobbes forward: there is no thinking the global body politic without its internal others, without borders and exclusions.

On the question of internal others, we have also managed ways of thinking about the global body’s malignancies as invaders that nevertheless reside inside the social corpus. This is why the virus is such a good metaphor: sure it starts from outside, but, conveniently, we can also act shocked when it reorganizes our cellular function: we can call it both foreign and self-same; incorporated (literally) and disincorporating, or disintegrating. The figure of the global body politic evolves as our understanding of disease evolves, and as the viruses themselves evolve: it is very good at othering anything that threatens the presumed norm of health, from inside or out.

KH: So far, we’ve been talking about religion a bit obliquely, as something presumably contained in the category of Islam and, much more troublingly, “Islamic terrorism.” One of the threads I found fascinating in your book was the way you trace the twin cholera epidemics to twin mass-movements of religious pilgrims: the first, among Hindu pilgrims in 1817, and the second, among Muslims traveling from India to Mecca on Hajj in 1831. Can you tell us more about how you think about religion in this genealogy of epidemiological thought and politics?

ARK: I want to be super clear that I don’t think religion per se has very much to do with these political ebbs and flows. Our mutual friend Abby Kluchin once blew my mind by explaining in incredibly straightforward terms something I should have realized before: that religion qua religion was, like almost every other divisive category, ossified by the massive knowledge-producing machinery of imperialism to taxonomize and divide people, to set them on courses of political self-sabotage and mutual destruction.

In modern South Asia, where a lot of my research has taken place, more people practiced and still practice daily spiritual lives that cleave to no single book or set of beliefs, that are fulfilling and opportunistic by turns, that change when they have to, and that insist on god as a mobile and flexible presence. This is also to say a lot of Muslims engage in non-Quranic practices of meaningful spirituality and so on and so forth. Likewise with every other “religion” I know.

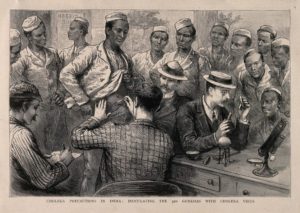

Cholera treatment in British-occupied India

Early epidemic studies looked for causes and sought to make sense of how people lived and moved. They were not really interested in what people worshipped or what they believed. It was politically expedient to displace the very real challenges to managing empire from environmental mistakes (the first cholera epidemic likely exceeded endemicity because of deforestation and military movement by the East India Company) and organized political action to “religious practice.” Turning “religion” into an ethnic and racial category made it easier for the historians and bureaucrats of the British and French empires to exonerate the movements of global trade in the dissemination of disease and to locate “heathen” worship as the source of rampant infection. When colonial officers, politicians, and bureaucrats began to describe religious ideology as “contagious” or “infectious,” they were building on myths they had already peddled about Hindu melas, Muslim hajj, Bedouin nomadism, and Near Eastern “filth and crowds” as permanent features of the “religions” they hated.

We’ve talked a bit about the chromatic racism (colorism) that accompanied the visual culture of Orientalism (there’s much more to say about that than can fit here)–Hindu art especially was ransacked for evidence of how diseased bodies were just like those of the infidel gods — blue, purple, black, incontinent, wasted, inhuman, and more. I’m not sure that the symptomatology of COVID-19 has been racially linked yet to horrible old stereotypes about East Asians, but there’s a deep and influential history in Orientalist discourse about the passivity and fatalism of Asiatics — linked to Buddhism, but also Hinduism and Islam — that I am guessing will become part of the racialized discourse of the pandemic soon. During our discussion, you sent me this article debunking the “Confucian obedience” fallacy with regard to the South Korean response to the pandemic — and I’m glad we have people writing against this kind of silliness with such speed — but I think we’ll see a lot more ethno-determinist takes in the coming months and years.

KH: As obviously relevant as your work is to thinking about Islamophobia and the pandemic, I found it also got me thinking about other recent events and crises. First, you reminded me that the concept of immunity is actually borrowed from the language of sanctuary — that is, a sacred space where one is protected from arrest. Which immediately made me think of the post-2016 election sanctuary movement, mobilized in the face of a president who referred to “migrant caravans,” deploying a rhetoric familiar from your archive in which cholera outbreaks were associated with “the arrival of ships, of caravans, of fugitives or pilgrims, of individuals, and with the progress of armies.” And now, since we began this conversation, Trump has declared the Coronavirus an “Invisible Enemy” that warrants the “signing of an Executive Order to temporarily suspend immigration to the United States! [sic]” Can we use epidemiological interpretation to think about anti-immigrant discourse, broadly speaking?

ARK: Absolutely. I don’t want to belabor the point, but I would say anti-immigrant and also homophobic discourse in the decolonial era is always tethered to and fully burgeons in the light of the epidemic metaphor, if not in the actual study of epidemics, where we also see entrenched racism and heteronormative violence being expressed in study design, outcomes, and pharmaceutical inequities. We have to maintain focus, for example, on the vilification of gay men, Haitians, and Sub-Saharan Africans in the AIDS crisis. It’s hard to talk about a figure used so promiscuously that it almost ceases to have meaning. What the coronavirus pandemic has revealed is that it never entirely ceases to have meaning, even when it almost does. I am thinking here of the way John Roberts, upholding the Trump “Muslim ban,” suggested that if an epidemic were to occur in a region, of course we would bar people from that place from entering the United States. Banning Muslim immigration to the U.S. in 2018 was premised on a not-yet-manifest idea of plague; the pandemic now retroactively ratifies this putatively racial exclusion.

KH: Similarly, citing examples such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s minor poem “Cholera Cured Beforehand,” you write about how:

[M]any scholars of cholera and its cultural history have shown the disorder’s ostensible preference for the lower class—evidence for example in the address of Coleridge’s poem to the ‘Useful Classes’— was only further accentuated by the way in which the disease seemed to inscribe itself of the body as an accelerated impoverishment.

Do we carry this through in our discourse now about “essential workers”?

ARK: I’m not sure we have language yet for identifying the bodily effects of this disease with cultural features we project onto others — Chinese people in particular, who have become the undeserving scapegoat in the worst versions of this story. Certainly there is something like aghastness and shock when people with access to what is supposed to be the most scientifically advanced, if far from the most egalitarian, healthcare system on the planet fall sick, are hooked up to ventilators, and die.

One of the things that I will say has been most infuriating as a sort of hopeful and well-meaning person during this time is seeing how often people revert to the ridiculous pabulum of “diseases know no race or class” — how the COVID-19 pandemic is the “great equalizer.” You certainly don’t need to be a scholar of disease and the history of epidemics to know that this is utter nonsense. The virus has no preference except for what allows it to proliferate, and there is no surer determinant of outcomes than economic privilege. The U.S. has seen — I want to say extraordinary, but the truth is they are utterly ordinary — disparities between the number of cases and deaths among working class people and communities of color and their white bosses, employers, managers, and neighborhood gentrifiers.

NYC subway on March 31, 2020

In New York City, where the pandemic has thus far inflicted the most devastating losses, these disparities are visible neighborhood by neighborhood; they magnify the already-indefensible environmental and economic abuse that maintain the second-class citizenship of Black and brown Americans, not to mention undocumented, detained, and incarcerated people. If we stop personifying disease as a thing that can have or express preference, we will be forced to confront our own social system’s preference for the already well and the already healthy, the total ejection of anyone not capable of or willing to submit their lives wholesale to the enrichment of corporate shareholders. If we do this, we will face the total demise of the economic system in which we are forced to live.

I say this in a hopeful way. I have been trying to come to terms with something I am calling “catastrophe mania” — that is, the weird admixture of sorrow and excitement that comes not only from being a person who thrives under conditions of extremity (good in a crisis, terrible under most other circumstances), but also from an embarrassing place of intellectual prepper’s comeuppance. The more serious writers and theorists I look up to have taught me to see the everyday we lived in before as a total emergency.[4] There is a comfort in feeling that others might finally have to recognize this state of affairs, that it might push us to do something about it. I reject in the strongest possible terms the kind of Zizekian nonsense that all but demands us to collective suffering for the sake of revolution. Fuck that opportunistic noise, even if the money from the book he has apparently already written about COVID-19 is allegedly going to Médicins sans frontières. Now that it is here, though, in spite of our best efforts, I would be lying if I said it hadn’t given me some hope in the last weeks. At the very least, hope that a few students would look at their lives and the choices they might make differently, with more urgency, and more energy toward the responsibility to others’ spiritual and physical wellbeing.

KH: Lastly, a maybe fun question: I want to talk shit. By beginning your study with cholera, we are knee deep in scatology the whole way through this work: from Coleridge’s poetic discharges to the Gates Foundation’s support for the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research. Of course, this shit isn’t funny. It’s based in centuries of racist renderings of Indians, and particularly Muslims, as unclean. But now, I’ve been observing a kind of return of the clean-assed repressed: from toilet paper hoarding, to a rush on bidets, to this quip on Twitter, to the New York City Department of Health’s memo on safe sex in the time of coronavirus, which defined “rimming” to much fanfare. I wonder what you think is going on here?

ARK: HA! Well, you’ve put your finger on it. I feel like a million years ago on the first day of an anthropology class someone said, “The first things we study are death, reproduction, and excrement,” all of which are wrapped up in this current moment’s anxieties. For LGBTQ people, as for racial others, these “concerns” are pernicious, policing, and often inflict further harm. I’m also thinking about the history and the present state of blood donation, nationalism, race, and the continued pathologization of queer sex. On a lighter note, I am obsessed with loosey goosey armchair sociology that posits Iraq’s relatively lesser death toll with Muslims’ obsessive five-daily ablutions, and Italy’s catastrophic outcome with “double cheek kissing.” I mean what unscientific cultural analysis, but also: we Muslims do love to wash! I have recently offered lota tutorials to anyone who will listen, and have been proselytizing about “Muslim showers” or commode-side spritzers for as long as I’ve been out of diapers. The NYC Health Department’s warning against rimming in a time of pandemic is joyfully joyless and anti-social. They also recommend self-pleasuring in the warmest terms. The tone is insane — I love it — it goes right into the canon of bad objects. I can’t wait for some wiser millennial’s take on corona-cooking, social distancing, and ass play. May we all resume rimming as usual in due course!

***

[1] For example: Frantz Fanon, “Medicine and Colonialism;” Francois Delaporte, Disease and Civilization; George Canguilhem, The Normal and the Pathological; Alan Bewell, Romanticism and Colonial Disease; Priscilla Wald, Contagion; Erin O’Connor, Raw Material.

[2] Susan Sontag, Disease as Political Metaphor, New York Review of Books, February 23, 1978 and AIDS and Its Metaphors, New York Review of Books, October 27, 1988.

[3] Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” trans. Libby Meintjes, Public Culture, 15.1 (2003), 11-40. 12.

[4] I’m thinking here of poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Mahmoud Darwish, and also scholars like Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Rob Nixon, Fred Moten, and Vanessa Agard Jones.

***

Kali Handelman is a Contributing Editor for the Revealer. She is also a freelance academic editor and the manager of program development at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.

Anjuli Raza Kolb is Associate Professor of English at the University of Toronto, where she teaches poetry and postcolonial theory and literature. Her scholarly book Epidemic Empire is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press in 2020, and she is completing two collections of poems: Janaab-e Shikva (Watchqueen), after the Pakistani poet Iqbal, and Mantiq al Tayl (Birdbrains). Her poems, essays, and translations from Urdu have appeared or are forthcoming in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Boston Review, Triple Canopy, The Poetry Foundation, FENCE, Critical Quarterly, Guernica, Words Without Borders, The Yale Review, and more.