Elisabeth Elliot, Flawed Queen of Purity Culture, and Her Disturbing Third Marriage

Was the famous evangelical woman in a manipulative marriage?

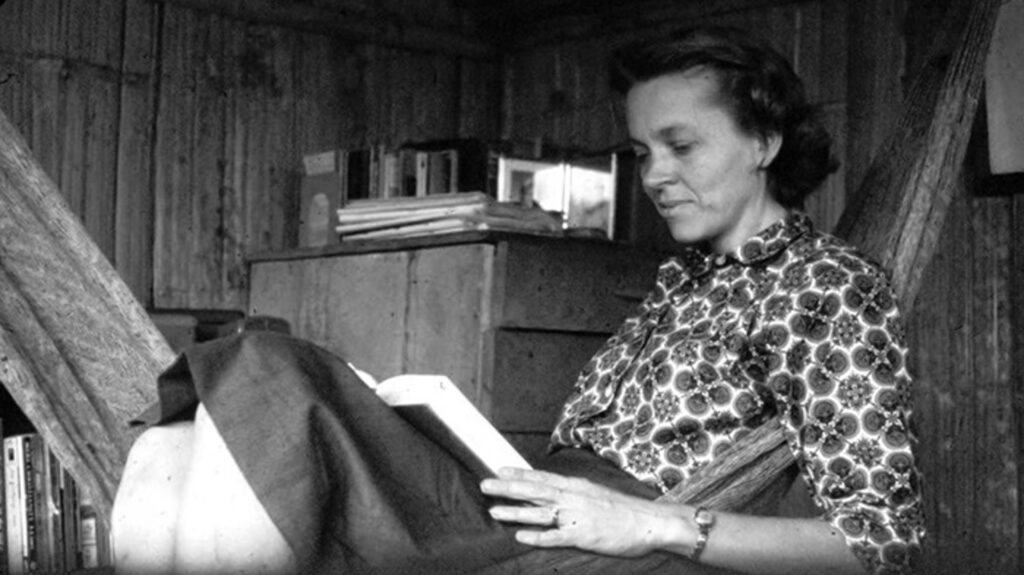

(Illustration of Elisabeth Elliot. Image source: East West Ministry)

Like many millennial evangelical women of the 2000s, I read Passion and Purity as a teenager, the memoir and advice book by purity culture pioneer, Elisabeth Elliot. Elliot’s 1984 epistolary account offers dating tips and tells the story of her courtship with Jim Elliot, her famed martyr husband who died of impalement at the hands of the “unreached” Waodani tribe in the jungles of Ecuador in 1956, while making passing references to the two husbands who followed him (she was widowed twice).

At 18, I consumed her words eagerly, hungry for romance, though I myself was single with no marriage prospects in sight. I loved her example of courtship, of “saving yourself” for ecstatic marital sex, of the hand of God directing a humble woman’s love life. But as much as I prayed to follow her example, it never worked for me.

Now, at age 36 and in a happy egalitarian marriage, I see her words differently. Today, I lean decidedly progressive in my politics and Christian beliefs, and so Elliot’s words seem not just dated or fantastical, but misogynistic.

I’m not the only one to find Elliot’s words polarizing. During her five-decades-long writing career—she published 48 books, spoke internationally at Christian churches and conferences, and gained household recognition through the 13-year run of her daily radio show—where she stoutly defended marital “complementarianism” as fundamental to the Christian faith. Complementarianism is a theological justification for patriarchal gender roles; it is the ideological underpinning of “purity culture,” a movement that taught teenagers that pre-marital sex will harm themselves and their future relationships and encouraged sexual repression (especially for queer and female teenagers). Like other purity culture leaders, Elliot emphasized marriage as the “penultimate human experience,” only topped by pregnancy for women or a life devoted to the church for men (even better: martyrdom for God). Elliot’s triangle of authority—God on top, then man, then woman—has resonated for decades within evangelical communities, influencing at least three generations toward conservative views on gender roles and sexuality.

Certainly, Elliot’s views have harmed women. Enforcing a culture of male dominance has consequences. Some of my friends have experienced marital rape and domestic violence in their evangelical marriages. Another friend found that her father expected her to become a “stay-at-home daughter,” and received limited education and even more limited freedom as a teenager. Others only recognized they were queer after they finally became sexually active in their heterosexual marriages.

Personally, Elliot’s teachings did not harm my sexuality as much as my sense of self. She taught that God was male. I took this to mean that men were holier and more like God, that I could never come close to the life demanded of me within the Scriptures, that I myself—my body, my femaleness—was inherently bad. As a result, I developed a binge eating disorder to hide myself, a disorder that I still struggle with to this day.

Because of Elliot’s prominence and ties to influential organizations and leaders, such as Bill Gothard of Shiny Happy People fame and James Dobson of Focus on the Family, Elliot became a controversial figure. Both conservative and liberal Christians made her a symbol of what’s right (or wrong) with Christianity’s relationship to women.

Yet as I read two recent Elliot biographies published in 2023, I did not see a symbol or figurehead, but a real live breathing woman. Lucy R.S. Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life (Crossway) released in June, and Ellen Vaughn’s Being Elisabeth Elliot (B&H Books), the second installment in a series on Elliot, came out in September. Elliot’s foundation and family commissioned Vaughn’s biographies and gained praise in conservative evangelical circles. Austen, on the other hand, undertook the task independently and earned praise from both the author of Jesus and John Wayne, Kristin Kobez Dumez, a respected feminist historian of evangelicalism, and The Gospel Coalition, a conservative evangelical online magazine known for its support of traditional gender roles.

To my surprise, after spending nearly 900 pages absorbed in the life of Elisabeth Elliot, I found myself less disturbed by her ideas and more disturbed by the trajectory of her life. Widowed twice, a wife of three husbands in all, her marital relationships appeared to become more dysfunctional the older she got, culminating in a third marriage both biographers describe circumspectly as loveless, disappointing, and manipulative, to put it mildly. In fact, one question still haunts me about the life of Elliot, the woman so enamored with love as to make it her career: was Elisabeth Elliot abused by her third husband? And if so, how should we evaluate her life and work?

Who was Elisabeth Elliot?

Elisabeth Elliot (Betty to her family) rose to prominence after her husband Jim was murdered in 1956. The couple had been serving as Brethren missionaries in Ecuador, translating the New Testament for Indigenous tribes when Jim and a group of other young missionary men undertook a dangerous mission to meet with the Waodani tribe, an uncontacted and war-torn Amazonian tribe. The men were killed within days of landing in the tribe’s territory, each speared through with a lance. Though Elisabeth and Jim had “courted” for years, they had only been married for three; their daughter was barely ten-months-old at Jim’s death.

Suddenly, alongside managing her grief, Elisabeth needed to decide whether to stay or leave the region (to her family’s astonishment, she chose to stay to try and reach the tribe that had murdered her husband). She had to adjust to single parenting while responding to dozens of interview requests. The deaths of five American missionary men in South America made headlines, including as a feature story in Time magazine. The other widows elected Elliot as their spokesperson. Over the next decade, Elliot published several books about her husband Jim and their missionary team and became a sought-after speaker.

(Elisabeth Elliot. Image source: International Mission Board)

This Elliot was not the “toe the party line” Elisabeth Elliot of purity culture fame. No, this intellectual widow in her thirties taught the Bible to both men and women (though it was controversial for women to teach the Bible to men), left her daughter at home with a friend to travel for her career, moved freely amongst the New York City literati (she shared a literary agent with Robert Frost and Madeline L’Engle), and openly expressed disdain at Christian publishing for habitually making stories “neat and tidy.” This Elliot courted the ideas of feminism and gained a reputation as being argumentative and opinionated. In fact, during this period, Elliot even published a controversial novel, No Graven Image, that, in no uncertain terms, criticized the church’s idolization of missionaries. (She received very mixed reviews.)

So, how did this woman become the female figurehead of the complementarian evangelical movement of the 1970s to 2000s, warning against the influence of feminism on the church?

Becoming an Advocate for Traditional Gender Roles

The answer to Elliot’s transformation can be found in examining her love life. Each of her three marriages led Elliot toward increasingly conservative ideas about the role and function of women within the home and church.

First, Jim Elliot: his journals inspired her own work for decades, and their relationship came to serve as an example she held out for others to follow in the coming years.

Then, Addison Leitch: an older conservative Presbyterian seminary professor who the biographer Austen describes as “tradition[al],…against questioning, an institutionalist to the core” who once wrote that “the conversation around women’s liberation is ‘stupid.’” Before her second marriage, Elliot had openly expressed disgust at the way Christian institutions adopted legalistic rules and expectations, such as advocating temperance despite Jesus turning water to wine. She had also conversed curiously with feminist Christians. However, after marrying Leitch, friends and family noticed that her views rapidly shifted to match her new husband’s, taking on an institutional bent, and arguing alongside her husband for the “unconditional obedience” of wives.

Last, Lars Gren: here lies Elliot’s most disturbing theological turn. When cancer overtook Leitch in 1973, Elliot was again widowed. She remained unattached for five years even as Gren, a seminarian who had rented a room from the middle-aged author, pursued her. Eventually, he proposed, telling Elliot, “I want to build…fences around you, and I want to stand on all sides.” The fifty-year-old woman often felt overwhelmed by the demands of her career and interpreted Gren’s words as protective and supportive. Unfortunately, Elliot misunderstood the intention behind these words. Gren meant his words literally: he wanted to fence her in.

Biographer Ellen Vaughn describes the logic of Elliot’s third marriage like this: “I could see… Elisabeth’s understandable loneliness, deep need for affirmation, physical hunger, weariness, and desire to be ‘protected’ [that] gradually, insidiously, led her, step by cajoling step, into a difficult third marriage that confined and controlled her for the rest of her long life.” Elliot “exchange[d]…freedom for security. She became a person whose highest value was the desire to feel secure.” Unfortunately, Gren had no safety to offer, and his presence only exacerbated Elliot’s pain.

His intentions became clear immediately, and Elliot later admitted to close friends that within hours of their wedding ceremony she realized she’d made a mistake in marrying Gren. According to Austen’s biography, when Elliot and Gren returned to their home to pick up their luggage, Gren refused to leave for their honeymoon, “until he was good and ready.” Apparently, earlier that day, Elliot had guided the couple as they left the church sanctuary (she steered them the opposite direction that Gren was walking), causing their friends to chuckle. This supposed humiliation made Gren furious, and he reasserted his control. Gren’s anger would define their thirty-eight-year relationship.

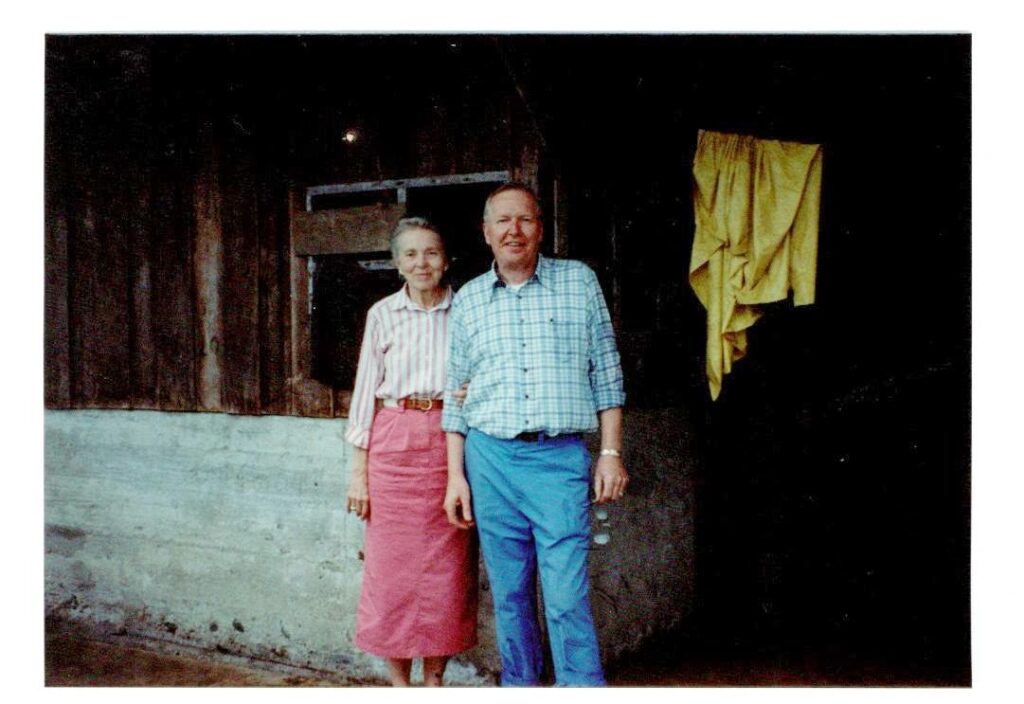

(Elisabeth Elliot with her husband Lars Gren. Image source: Family Life Today)

Both biographers describe a dramatic curtailing of Elliot’s freedom after her third marriage. Gren decided when she drank a cup of tea, took a bath, and when she slept. He frequently checked her car’s odometer, double-checking that she hadn’t made any unplanned stops. He controlled the house thermostat. He listened in on her phone conversations and had the final say on whether she visited her friends, often declining invitations for her at the last minute. When he grew angry with his wife, he would refuse to speak to her for days. And most painful for Elliot, Gren “unpredictably denied her access to the daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren she loved,” Vaughn writes.

The manipulations worsened as Elliot’s husband took over management of “the Elisabeth Elliot industry,” as Austen termed it in an interview. Austen writes, “He introduced her at the podium, adjusted her microphone, managed the book table, and made sure she ate. He decided when she rested and when she worked and when she socialized…he berated her for errors in speaking…even critiquing her posture.” Gren kept up a grueling speaking schedule for the introverted Elliot, who often experienced nightmares about public speaking and would have preferred to retreat from public life in her later years. However, she submitted to Gren’s relentless expectations, and so her influence continued to grow (to her chagrin).

Elliot maintained a whirlwind of speaking engagements long after her Alzheimer’s diagnosis in the 1990s because of Gren—even after she’d lost the ability to speak. At least once, Gren had her sit on stage smiling while Gren played a tape of a speech she’d recorded years earlier. Only when a doctor ordered the end of her travel did she find relief from her husband’s demands.

“Obey Regardless of Your Feelings”

Elliot’s later theology reflected the authoritarianism of her third marriage. Both Gren and Elliot shared the conviction that a wife should subordinate herself to her husband. And so, a new theme emerged in Elliot’s writings: obey God regardless of your feelings. Elliot seemed to apply this statute liberally, seemingly substituting “Gren” for “God.”

For example, she attached significance to a moment when a friend told her to work harder at accepting her husband, sinner and all, after Elliot obliquely mentioned some marital troubles. “That instance was so sad,” Austen told me in an interview, “[That advice] would [have been] fine if the problem Elisabeth was dealing with in her marriage to Lars is that he loads the dishwasher differently. But it wasn’t.”

In fact, Elliot recounted the story of her friend’s advice to her newsletter readers, writing that her role was to “accept the divine order” and practice selfless love toward her husband, even when he had sinned against her. When women readers wrote her letters asking for advice about their abusive or dysfunctional relationships, Elliot wrote back, “Examine your own heart to see if there is ‘any way in which you are pushing your husband, challenging or aggravating him.” Austen elaborates, “[This] advice [offered by Elliot]…reinforces the misconception that the victim is doing something to deserve abuse and the abuser is justified in lashing out.”

While records do exist of Elliot writing against abuse (“There are things which must be changed, such as the abuse of persons…,” and “I do not want to be understood as recommending a woman’s surrender to evils such as coercion…”), it’s hard to ignore the disturbing theme between her patriarchal theology and the facts of her abusive third marriage. Gren was a younger man who manipulated his famous, successful, and powerful wife until he controlled every minute of her time, attention, and work.

Domestic abuse addles the brain. A victim may begin to believe she deserves this kind of treatment, that she could perhaps stop the abuse by her own efforts—if only she were better, prettier, smarter, holier. Through this lens, I have begun to understand the complexity of this elderly woman whose livelihood depended on her teachings about marriage and whose theology shifted so that it matched her reality of suffering, obedience, and surrender. Perhaps she feared the consequences of divorce on her career or reputation.

An interview with Elliot in Christianity Today, the conservative Christian magazine founded by Billy Graham, just months after marrying Gren, sheds a light on this shift in her theology. She criticizes high American divorce rates, blaming couples for confusing the feelings of infatuation with the committed love of marriage, writing, “At a feminist convention I heard a woman say that marriage and motherhood are like deaths. She deplored this. But that’s exactly what it’s supposed to be. When a woman marries, she dies to her past, her name, her other commitments, her identity, and herself.” And why? Because, “Jesus says he that loseth his life, shall find it.”

“Marriage as a death” gives us one explanation for Elliot’s troubling marriage to Gren. But why did she stay married for thirty-eight years? Those who knew her best undoubtedly asked themselves the same questions. Vaughn describes the mounting concern of friends and family about Gren, especially after her dementia diagnosis: “[They] worried that Elisabeth’s once-strong spirit had been crushed. [So,] the family staged an intervention, removing Elisabeth, who had agreed, to an undisclosed location outside the United States.” During that time, they asked Gren to change, to repent, to soften. To back off her speaking schedule. To give his wife rest. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that he listened, and the standoff only ended when “Elisabeth herself begged to go back to Lars. ‘He is my husband,’ she said, ‘He is my head.’”

Perhaps it would have been more accurate for Elliot to explain that without her husband, she had no identity, no purpose, no past. Because, to Elliot, marriage became a means of martyrdom. And submission—the total death of the self for the sake of God—became her life work.

The Truth Comes Out

For decades, my own grandmother, who I called Meema, was abused by her second husband, whom she married after the love of her life unexpectedly died of a heart attack at age 40. Weary of parenting twin girls alone, uncomfortable with her singleness, hopeful for companionship and needing help to pay her bills, she married a charming man in the 1960s. He met none of her expectations, and at seventy, she was hiding bruises on her arms under long sleeves. She refused to leave him or tell the other members of her church choir about the tumult of her home life. Only one dear friend knew the truth. Eventually, my grandmother was freed from her marriage when her husband entered a nursing home and passed away, leaving her decades of unhindered life to heal.

Why mention my grandmother’s story? Because she has helped me to understand Elisabeth Elliot. Elliot was not as lucky as my Meema. Elliot died first, in 2015, before her abuser. And lest we ask Elliot to speak from the grave, Gren burned many of the journals she’d filled during their years of marriage, leaving us with few records to decipher her last decades. As Alzheimer’s stripped language from the prolific author, Gren also erased her private voice, too: the final indignity for a writer.

I still disagree emphatically with Elliot’s conclusions about womanhood, yet Austen and Vaughn’s biographies offer a rare glimpse behind the curtain. There, we see a woman who, in seeking to offer healing and direction to readers, instead enabled perpetrators to thrive and upheld a culture that ignored the suffering and abuse of women. She was a woman seemingly unaware of the harm her words caused, unaware of the dissonance between the advice she upheld as the “ideal” and of the life she herself had lived, and unaware of the freedom that would have lain on the other side of a divorce.

In fact, she did not understand her own worth; she saw herself as a slave of men and God alike, subservient to their whims and feelings even as she suppressed her own.

My ambivalence became stronger, however, after talking with Lucy R.S. Austen about the woman in question. Austen told me that she began to see Elliot’s career as responsive. “She was always responding to what other people were asking of her,” she told me, “To some extent, I think she got backed into being ‘the Evangelical voice’ because people kept looking to her for answers…People were writing to her and she was getting 500, 1,000 letters a week asking, what do I do about my love life? What do I do about this difficult relationship? So, she was writing books to answer those questions. And she kept trying to say, Elisabeth Elliot isn’t the Bible and you should read your Bible instead of asking Elisabeth Elliot…but people just kept asking Elisabeth Elliot [anyway].” White American evangelicalism needed a symbol, a meek female voice seated at the patriarch’s table — and Elliot complied.

Now, I’m left pondering Elliot’s legacy. Consider how different her legacy would have been had she divorced her abusive husband. How would a celebrity divorce like Elliot’s have changed evangelicalism? How might Elliot herself have changed? In fact, how might evangelicalism be changed now by this revelation about Elliot? That is, if the public hears the truth at all.

As I read reviews of Austen’s and Vaughn’s biographies and interviews with the authors, I discovered a troubling trend: evangelical publications who reviewed the books—such as Christianity Today, The Gospel Coalition, and World’s podcast and magazine—leave off mentioning Lars Gren. They never address the dissonance between Elliot’s teachings and her third marriage. Not one review uses the word “abuse.” In fact, both Elliot biographies omit the word, too.

What do evangelical institutions today gain by obscuring the truth about Elliot’s third marriage? What makes them so hesitant to admit the failures of their leaders when doing so might offer healing to their victims?

Perhaps they find the truth threatening. In her best moments, Elliot didn’t. She once wrote, “It is truth alone which liberates.”

I suggest we follow her advice.

Liz Charlotte Grant (on Threads, Instagram and Facebook @LizCharlotteGrant) is an award-winning freelance writer in Denver, Colorado whose newsletter, the Empathy List, has twice been nominated for a Webby Award. She’s published essays and op-eds at Religion News Service, Huffington Post, Sojourners, and elsewhere, and her debut book, Knock at the Sky: Seeking God in Genesis after Losing Faith in the Bible, releases in 2024 with Eerdmans publishing.