El Pueblo de Israel: Latino Evangélicos and Christian Zionism

Why have so many evangelical Latinos embraced Jewish rituals and Zionism?

(Photo: Menahem Kahana for Getty Images)

I awoke during the church service, sweaty from the sun that hit the pews at noon every Sunday. My father, full of the spirit, was still singing—with tears in his eyes and sweat on his brow. He had one hand in the air and another on the microphone, leading la congregación in worship. His back was draped with a tallit, a prayer shawl typically worn by Jews, and a kippah that covered the crown of his head.

La Iglesia Evangélica Menonita was one of many Spanish-language evangelical churches in the Washington D.C. area that welcomed the Holy Ghost on a weekly basis. The parishioners not only welcomed it, they asked it to come—and to come in power. This power manifested itself in people’s bodies and in their speech, serving as proof that the spirit was real and working among us. Some congregants believed this power could be amplified through a special connection not only with God, but also through a connection with his chosen people, the Jews.

And so, some in my family’s church embraced a fusion of Judaism and Christianity in the form of Messianic Judaism while others adopted Jewish aesthetics, rituals, and practices. The church incorporated Jewish traditions and objects like the shofar into spirited worship services. Parishioners emphasized how these practices brought them closer to God, the Holy Spirit, and the Jewishness of the historical Jesus. But this Charismatic Jewish cosplay was often accompanied by sermons, videos, and presentations about the modern state of Israel and the end times.

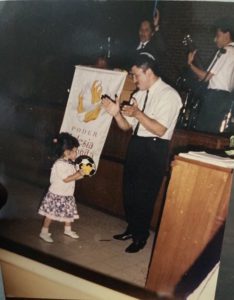

(The author as a child with her father wearing a kippah in church. Photo courtesy of Amy Fallas.)

My own father was captivated by the incorporation of Jewish elements into his Christian worship, and he was equally inspired by the state of Israel. He started to wear a kippah at church and at home when he prayed. He searched for a possible Sephardic Jewish heritage within his ancestry. When I was young and scared at night, I would run to the living room calling for my dad. He told me I shouldn’t be afraid because the God who protected Israel during the Six Day War in 1967 was the same God who would protect me in my room at night. With this proof of divine protection, I learned from an early age to link my own comfort to that of the modern nation-state of Israel.

This is how our Spanish-speaking, Central American evangelical family became Christian Zionists. It happened gradually, without realizing it and without us naming it as such. In fact, my parents did not know the meaning of Christian Zionism as a term until decades after their experiences in La Iglesia Evangélica Menonita. Yet our religious and political commitments made our family but one of millions of Latino evangélicos who embraced Christian Zionist beliefs.

Christian Zionism

Christian Zionists believe that support for the modern state of Israel is a scriptural obligation with ramifications for the end of times. Although Christian Zionism is a political and religious ideology that began during the early nineteenth century, its emphasis on the apocalypse grew in popularity in the United States following the reunification of Jerusalem during the 1967 War. Prominent evangelical figures such as Hal Lindsay, John Hagee, and Pat Robertson preached that a rapture of believers and a reckoning with God’s chosen people will unfold in the state of Israel, the Promised Land. This Christian Zionist vision of the last days, and its attendant reliance on Israel, is most commonly associated today with white evangelicals.

But south of the U.S. border in early 2011, a much different group demonstrated its support and love for Israel at a Messianic evangelical concert. As worshippers enthusiastically welcomed a blast of shofars and fog machines, a heavy-handed percussion provided the baseline for the interweaving sounds of Paul Wilbur’s characteristic Hebraic style. Wilbur, a Jewish-American convert to Messianic Judaism, started his music ministry to reach Jews for Jesus in the United States. By the 1990s he was one of the most popular artists in Spanish-language worship music. Songs such as “El Shaddai,” “Baruch Adonai,” and “Levántate Señor” were in regular rotation in evangelical and Charismatic Latino churches across the hemisphere. With his growing popularity, Wilbur ultimately performed in every Spanish-speaking country from Cuba to Honduras and Mexico to Latino congregations in the United States. His embrace of Judaism and Christianity paired with his public support for Israel relayed social, political, and religious messages that reflected the beliefs and discourses of Latino evangélicos in the United States and abroad.

With increasing popularity since the 1990s, evangelical and spirit congregations in Latin America began adopting Jewish symbols like the menorah and Star of David to brand their churches. They started to conflate modern Israel with Judaism and claim allyship with the biblical ‘Pueblo de Israel’ (the people of Israel). While eschatology was one focal point of these changes, their understanding of Israel and Jews drew from eclectic sources and their reasons for embracing aspects of Christian Zionism were varied. Some Latino evangélicos began to speculate about their possible Jewish roots, while others wanted to satisfy their longing for biblical authenticity by emulating Jesus’ Jewishness. But most of them wanted to tap into the divine power and promised blessings of supporting God’s chosen people.

Although they see themselves as allies, the Christian Zionist support for Jews is often contingent and at times even antisemitic. Many proponents of Christian Zionism simultaneously believe that while Jews will not be spared Hell unless they accept Jesus as the Messiah, a global convergence of Jews in Jerusalem is a pre-requisite to Jesus’s second coming. For centuries before a formalized Christian Zionism took shape, Christians espoused forms of Judeophobia that considered Jews as Christ-killers, heretics to be converted, and as a group Christians had replaced as God’s covenantal people. In recent years, ‘new’ Christian Zionists have tried to distance themselves from these antisemitic origins and theologically self-serving views; yet they continue to prioritize allyship with certain Jewish groups (Messianic and Israeli Jews) over others (Orthodox and anti-Zionist Jews).

Although the adoption of Jewish customs and symbols for Latino evangélicos does not always translate to support of Christian Zionism, the shared aesthetics and tendency to equate Jewish and Israeli identities contributes significantly to how Latino evangélicos understand and articulate their religious and political relationship to Israel, Zionism, Judaism, and Christianity. Organizations like the Latino Coalition for Israel or Philos Latino specifically emphasize these commonalities to marshal Latin American and U.S.-based Latinos toward a pro-Israel position. Collapsed distinctions and reductive assumptions inform what Latino evangélicos believe about Israel and Jews, as they do in the broader U.S. evangelical context: that Judaism and Zionism are synonymous, that Jewish safety can only be guaranteed through the Israeli state, and that Jesus cannot come back unless Jews return to the Promised Land. As Latino evangelical communities continue to grow in size and influence in the United States, so too are these associations between supporting Jews and the state of Israel.

In the Land of Egypt

It wasn’t until I studied abroad in Egypt when I met a Palestinian Christian for the first time that I began to question what my family and so many Latino evangélicos believed was the Christian obligation to support Israel. As I sat in a classroom at the American University in Cairo during the Fall of 2010, a young, impassioned professor told us that the situation in Israel-Palestine was not thousands of years old. She told us that Zionism—the idea of a Jewish homeland, fashioned according to the parameters of a modern and Europe-styled nation-state—was relatively new. The seemingly forever wars in a forever conflict of a biblical Middle Eastern sibling rivalry from time immemorial, as I had been taught, was not the reason for the series of events in Israel and Palestine over the last one hundred years.

As the professor spoke, I uncharacteristically averted my eyes for fear that I would be called on to speak. I wanted to say so much and nothing at all. In earnest, I wanted to challenge her — to tell her that my parents said Isaac and Ishmael’s fight over their divine inheritance was the source of Palestinian-Israeli enmity. That God had promised this land to the Jews. That this promise had future ramifications. That Jesus would return to affirm himself as the Messiah. But more relevant to this academic context, I wanted to tell her that the Israelis in a “realpolitik” sense had legitimacy — that they conducted themselves as “proper” citizens of a nation-state in a world of nation-states.

I believed all of those things because questioning those teachings would bore into the foundation of my beliefs about myself, my faith, and the world. Beyond my own parents’ authority, questioning the Christian support of Israel meant I would have to question our religious exegesis, to consider that we might have misread prophesy or misunderstood God’s promises. I would have to wrestle with a worldview that had been uncontested for twenty years of my life.

It was during these class-time internal struggles that I learned about the rampant antisemitism Jews faced during the nineteenth century that contributed to the formation of Zionism. It had not been the treatment of Jews in the Middle East, but rather antisemitism in Europe that prompted European Jews to respond to their widespread discrimination and persecution with ideas of establishing a Jewish state. I learned that many Christian Europeans who supported a Jewish homeland did so in order to avoid including Jews in European nation-states—a hypocrisy German-Jewish theorist Hannah Arendt critiqued throughout the twentieth century. The United States also restricted Jewish migration, even asylum seekers during World War II as a threat to national security.

I also learned about Palestine for the first time while in Egypt. It was a glaring absence from my homeschooled-to-Christian college education. And it was here that I devoured new information that would transform my worldview. I learned that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians of all faiths — Muslims, Christians, and Jews — had lived and prospered from Haifa to Jerusalem to Ramallah during the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

But during World War I, the British made claims to Palestine, promising a Jewish homeland therein, and secretly agreeing to divide the Middle East into spheres of European control. Under the veneer of the authority of the League of Nations, the British appointed themselves as the legal stewards of Palestine following the war and imposed a system of semi-colonialism known as the Mandate for Palestine. Decades later, their withdrawal from Palestine came in conjunction with the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 that outlined a Palestinian and Israeli state—undermining the sovereignty and self-determination of Palestinians in the interest of Yishuv settlers.

But during World War I, the British made claims to Palestine, promising a Jewish homeland therein, and secretly agreeing to divide the Middle East into spheres of European control. Under the veneer of the authority of the League of Nations, the British appointed themselves as the legal stewards of Palestine following the war and imposed a system of semi-colonialism known as the Mandate for Palestine. Decades later, their withdrawal from Palestine came in conjunction with the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 that outlined a Palestinian and Israeli state—undermining the sovereignty and self-determination of Palestinians in the interest of Yishuv settlers.

When the professor talked about the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, it was like a language I had never before heard. I had previously learned about the Shoah (the Holocaust) during World War II and Hitler’s horrifying genocidal policies towards Jews. I had always assumed the Holocaust ultimately led to Israel’s formation. But I had never learned that when Holocaust survivors arrived in Israel—they were “scorned and laughed at” by Israelis, “seen as weak victims at a time when the state was being led by domineering fighters.”

Palestinians experienced 1948 as “the Nakba” (the catastrophe), an event that initiated an exodus of over 700,000 Palestinians from their homes as a result of Zionist policies. Although the removal of Palestinians started before 1948, the creation of Israel accelerated the depopulation of Palestinian villages as Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) consolidated land and secured mobility within Israel. Among the most notorious incidents included operations Dani and Dekel, which authorized the removal of Palestinians in Lydda and Ramle—two towns that presented logistical barriers to Israeli transportation between their settlements. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and IDF deputy commander Yitzhak Rabin ordered the expulsion of 50,000-70,000 Palestinians in Lydda and Ramle in July 1948.

When I realized that my professor, a Palestinian Christian, did not accept the foundational assumptions of Christian Zionism, I started to question why I felt obligated to accept this ideology. How was I supposed to articulate a Biblical justification for the dispossession and displacement her Christian family experienced? As I started to learn about historic and contemporary Palestinian resistance to Zionism, I discovered it was not only possible to be Christian and reject this ideology—but that Christian communities in the very place where Jesus was born were some of the leaders of this approach. In contrast to what I had been taught in my evangelical Christian upbringing, the establishment of the state of Israel was not an immaculate conception; it was born out of violent displacement.

Christian Zionism between Latin America and the United States

In my mother’s home city of San Salvador, it is nearly impossible to drive anywhere without reading a reference to an Israeli city or to see Stars of David and menorahs with Hebrew letters on Protestant churches and religious complexes. The Tabernáculo Bíblico Bautista, for instance, is one of the dominant evangélico church networks with thousands of churches across the country. They became associated with Israel because of their church-sponsored trips to the Holy Land and the incorporation of “amigos de Israel” or “friends of Israel” as part of their ecclesiastical identity. Some of their religious complexes are huge, often including cafeterias, bookstores, schools, and recreation halls that pay visual homage to this desire to connect Latin America with Israel.

(Jewish iconography spotted in Latin America. Photo courtesy of Amy Fallas.)

Jewish and Israeli iconography is ubiquitous in Latin America and most commonly associated with the spread of evangelicalism. Yet explicitly pro-Israel views in places like El Salvador are most aligned with churches and parishioners of Pentecostal and charismatic traditions, a phenomenon that has grown in recent years. Historian Daniel Hummel notes that while white evangelicals were once the dominant group embracing Christian Zionism, this ideology is growing in popularity on an international scale.

Latino evangélicos have been actively targeted by Zionist organizations in the United States. The largest pro-Israel lobby groups such as Christians United for Israel (CUFI) and American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) have Latino and Hispanic outreach efforts, while more organizations have been established specifically to strengthen the Spanish-speaking community’s support for Israel. In 2019, the Latino Coalition for Israel (LCI) organized a summit in Jerusalem for approximately 200 Latino evangelical leaders. This gathering built on the heels of earlier efforts to bring Latino evangelicals and Israelis together, such as the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference (NHCLC)/Conela’s partnership with the International Christian Embassy Jerusalem (ICEJ).

Another prominent initiative known as “Philos Latino” was established by The Philos Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to “promoting positive Christian engagement in the Near East.” This outreach program targets the Latino community and offers educational resources, programming, and immersion trips to Israel. The most active component of the project is an online Spanish show called ‘Philos Conectam,” wherein the project’s director, Jesse Rojo, invites special guests to discuss issues related to their goals of promoting positive Christian engagement and pluralism in the Middle East.

Yet these seemingly innocuous, and even noble, efforts to educate and connect Latinos on issues related to the Middle East are overshadowed by its clear one-sided stance. Most of the topics of discussion on “Philos Conecta” are almost exclusively about, and in support of, Israel with little representation of alternate viewpoints. Over the course of 2021, the show’s episodes focused heavily on Guatemala’s positive diplomatic relations with Israel and their support of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, featuring conversations with the Guatemalan and Honduran Ambassador to Israel among other delegates and representatives. This programmatic focus is largely connected to the fact that the Philos Project was established with funds from pro-Israel philanthropist Paul Singer— demonstrating a clear set of interests given the organization’s funders, affiliates, and activities.

While these projects and outreach efforts illustrate a trend of Spanish-speaking evangelicals embracing Christian Zionism, this is not a monolithic view. According to a study conducted by Lifeway Research, Latino Christians do not consider Israel a major concern even as they hold generally favorable views of Israel. Also, even as Latino Christians view Israel favorably, a significant number of them “hold somewhat anti-Semitic views” – illustrating a familiar dynamic in which a pro-Israel perspective does not necessarily indicate a positive view or relationship with Jews.

And some Latino Christians, on the other hand, are openly critical of Zionism. In an interview with the current president of the Asociación Salvadoreña Palestina, Don Siman Khoury, said that his own family background as a Protestant and Orthodox Palestinian attests to the fact that Christian support for Israel is not a forgone conclusion. Salvadorans can be Christian, critical of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, and purveyors of peace in the region. After all, Khoury said, “God is more than just a distributer of land.”

***

In May 2021, an unprecedented wave of popular support for Palestine emerged in response to Israeli settler and state violence against Palestinians in Sheikh Jarrah, Gaza, and the West Bank. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in cities across the world to demand Palestinian rights and to call upon foreign governments to stop supporting Israel’s aggression. Even more spoke up online across social media channels, through virtual teach-ins, and in op-eds to engage new and longstanding allies to rally in support of Palestinian sovereignty and lives. Even amid the outrage of witnessing Palestinians being forced from their homes in East Jerusalem and Israeli bombardments in Gaza, people felt things were changing. Moral authority was shifting in favor of Palestine.

As I marched alongside protesters at one of the many rallies in Washington D.C., I spotted a sea of usual suspects: college students, Palestinian activists, and representatives from advocacy organizations. But I also saw young families, interfaith religious leaders, and people of all backgrounds and walks of life. I spotted a sign: “Latinos for Palestine.” Not too far ahead of me, young Jewish students held another sign: “Jews against Zionism.” It was beautiful to march with Jewish, Latinx, Palestinian, Muslim, and Christian protesters. Maybe there were others in the crowd who shared my upbringing— Latino evangelicals taught to support Israel unequivocally — now dressed in the Palestinian keffiyeh with signs raised in solidarity with Palestine.

When I was young, I could not have imagined this kind of solidarity. That was, and is, a central shortcoming of Christian Zionism — its inability to imagine beyond a foretold future. As I marched across downtown D.C., I felt a renewed sense of hope — if I was able to re-evaluate my own position on Israel — surely more Latino evangélicos would find this path too. Maybe it was a renewed sense of hope. Maybe it was the spirit moving among us.

Amy Fallas is a writer, researcher, and Ph.D. Candidate in History from Washington D.C. She writes about religion and tweets @amy_fallas.