Ecopiety: Green Media and the Dilemma of Environmental Virtue

A book excerpt with an introduction by the author.

Climate change is the biggest existential challenge we as a collective species have ever faced. The planet’s rising temperature and the concurrent severity of worldwide weather patterns are macro problems. So why are we so focused on tiny, individual, voluntary acts of environmental piety to address phenomena on a colossal scale? We are saturated with environmental media messaging―much of it corporate-driven―that reassures us that the most effective way to take environmental action―to make real and effective change―is to buy or consume the right things. There are strong, vested, corporate economic interests in keeping us distracted, complacent, and self-assured that we have done our part in these small, simple acts to “save the planet.” I call these individual practices “ecopiety.” In Ecopiety: Green Media and the Dilemma of Environmental Virtue, I lay bare how discourses of environmental virtue re-direct the global climate crisis from collective politics to the choices of individual consumers. The book aims to change the conversation from what “I” can do as a consumer to save the earth―because the answer is not much, if anything―and shift that question to what “we” can do collectively as engaged citizens to fight climate change in ways that will actually move the needle on global temperature. Ecopiety redirects environmental messaging about climate action away from the dominant narrative of green capitalist consumerism and individual lifestyle choices to messages focused instead on substantial public investment, collective action, broad-scale policy changes, and their widespread implementation.

This excerpt comes from the book’s Introduction.

***

“It’s 3:23 in the morning and I’m awake.” A man sits up on the side of his bed with his head in his hands, running his fingers through his thick brown hair in frustration, and we as the viewers get the sense that he is being haunted by some unseen force. The eerie sounds of Icelandic rock band Sigur Rós front man Josí playing guitar strings with a rosined cello bow evoke the creaks and groans of calving glaciers. The scene shifts to the twinkling lights of the Golden Gate Bridge in the San Francisco night sky, and the man is now up and dressed, soberly staring unblinkingly at us. He explains: “I’m awake because my great-great-grandchildren won’t let me sleep.” Images of children playing on merry-go-rounds and swinging on swings sequence one after another. “My great-great-grandchildren ask me in dreams,” he continues, “what did you do while the planet was plundered? What did you do when the earth was unraveling?” Images flash of power plants, polluted skies, melting arctic ice, seals searching in vain for land, sea birds blackened in crude oil, choked highways, burning oil fields, and bomber jets headed off to war in what appears to be the Middle East. The great-great-grandchildren’s questions fill the man’s head and are unrelenting. They want to know of him, “Surely you did something as the seasons started failing? As the mammals, reptiles, and birds were all dying?” The children press further and demand, “Did you fill the streets with protest when democracy was stolen?” Their final question hangs heavy in the air as a haunting refrain of accusation: “What did you do once you knew?”

“It’s 3:23 in the morning and I’m awake.” A man sits up on the side of his bed with his head in his hands, running his fingers through his thick brown hair in frustration, and we as the viewers get the sense that he is being haunted by some unseen force. The eerie sounds of Icelandic rock band Sigur Rós front man Josí playing guitar strings with a rosined cello bow evoke the creaks and groans of calving glaciers. The scene shifts to the twinkling lights of the Golden Gate Bridge in the San Francisco night sky, and the man is now up and dressed, soberly staring unblinkingly at us. He explains: “I’m awake because my great-great-grandchildren won’t let me sleep.” Images of children playing on merry-go-rounds and swinging on swings sequence one after another. “My great-great-grandchildren ask me in dreams,” he continues, “what did you do while the planet was plundered? What did you do when the earth was unraveling?” Images flash of power plants, polluted skies, melting arctic ice, seals searching in vain for land, sea birds blackened in crude oil, choked highways, burning oil fields, and bomber jets headed off to war in what appears to be the Middle East. The great-great-grandchildren’s questions fill the man’s head and are unrelenting. They want to know of him, “Surely you did something as the seasons started failing? As the mammals, reptiles, and birds were all dying?” The children press further and demand, “Did you fill the streets with protest when democracy was stolen?” Their final question hangs heavy in the air as a haunting refrain of accusation: “What did you do once you knew?”

How many of us imagine that we might adequately answer that weighty last question one day by responding, “Well, I made sure to shop for the right stuff. I bought green products, I shopped organic, I supported green capitalism, purchased ecologically mindful cell phone apps, a nice recycled beverage container, a hybrid vehicle, and generally consumed my way to helping solve global climate change and save the earth.” Would this satisfy the specters of our future offspring who wish to hold us morally accountable for the state of the earth they have inherited? And yet, much of the environmental messaging we encounter on a daily basis through marketing, advertising, and mediated popular culture is simplistically reassuring and absolving. Shop for the right stuff, and it will all be okay.

The voiceover in the video recounted above, which was created by Bay Area–based spoken-word poet and filmmaker Drew Dellinger, features an excerpt from his longer poem, “Hieroglyphic Stairway,” drawn from his award-winning book of environmentally themed poetry, Love Letter to the Milky Way. Dellinger, who also holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and religion, jolts us awake from the complacent fantasy that we can sit back, make minimal changes, and it will all be okay. His video intervenes in these reassurances, telling a different story—one of late-night hauntings and the horror of deep regret as we are called on the carpet by our suffering descendants for failing to act when we might have. Dellinger’s video goes on to show hopeful images of protests filling the streets, of student activists braving pepper spray and police, and of arts and culture leading the way to a vibrant and sustaining ecological human culture. But the haunting question hovers, “What did you do once you knew?” The correlative question once was what will it take to ensure we never face the haunting questions this video conjures? But we are already being asked this question by children, not off in the future, but in the now. And yet, consumer culture repeatedly sets our minds at ease that individual acts of environmental virtue will do the trick. Dellinger’s answer is broader ranging and calls for more—more imagination, more collaboration, more connection, and more coordinated acts of conscious collective social transformation. Borrowing a phrase from the work of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., the final words of the video appear as striking white letters glowing against a black screen: “Planetize the movement.”

The voiceover in the video recounted above, which was created by Bay Area–based spoken-word poet and filmmaker Drew Dellinger, features an excerpt from his longer poem, “Hieroglyphic Stairway,” drawn from his award-winning book of environmentally themed poetry, Love Letter to the Milky Way. Dellinger, who also holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and religion, jolts us awake from the complacent fantasy that we can sit back, make minimal changes, and it will all be okay. His video intervenes in these reassurances, telling a different story—one of late-night hauntings and the horror of deep regret as we are called on the carpet by our suffering descendants for failing to act when we might have. Dellinger’s video goes on to show hopeful images of protests filling the streets, of student activists braving pepper spray and police, and of arts and culture leading the way to a vibrant and sustaining ecological human culture. But the haunting question hovers, “What did you do once you knew?” The correlative question once was what will it take to ensure we never face the haunting questions this video conjures? But we are already being asked this question by children, not off in the future, but in the now. And yet, consumer culture repeatedly sets our minds at ease that individual acts of environmental virtue will do the trick. Dellinger’s answer is broader ranging and calls for more—more imagination, more collaboration, more connection, and more coordinated acts of conscious collective social transformation. Borrowing a phrase from the work of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., the final words of the video appear as striking white letters glowing against a black screen: “Planetize the movement.”

Piety, Virtue, and Saving the Planet

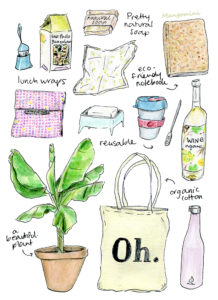

“Eco-friendly,” “green,” “environmentally sustainable,” “ecologically mindful,” “earth-conscious,” “environmentally responsible,” “planet-friendly,” “eco-smart,” and even “eco-elegant” are just some of the sobriquets used in popular parlance and consumer marketing to signal products, services, acts, behaviors, or lifestyles associated with the practice of a kind of environmental virtue, or “ecopiety.” Piety, a complex social, civic, philosophical, and religious designation, is classically considered to be a virtue associated with the practice of appropriate duties or obligations. The Greek term “eusebeia” (“εὐσέβεια”) connotes reverence and respect in engaging in right behavior or service that pleases the gods. In the ancient world, the Roman ideal of pietas was associated with “dutifulness to parents, homeland, and emperor,” and with maintaining good relations with the gods—acts that if performed well were often credited for Roman empiric success. The proper performance and practice of pietas, in Roman terms, also suggestively correlated with the maintenance of order in the universe and the sustaining of the world. Some scholarship on religion in the ancient world has probed the complex sociopolitical and economic transactional value of pietas in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean “ideological marketplace.” This book explores the marketing, representation, and popular mediation of environmental piety in our own contemporary “ideological marketplace,” its contested cultural meanings, and its complex transactional value in the lives of North American consumers.

Eco Consumerism

“Ecopiety” is a shorthand term I use to refer to contemporary practices of environmental (or “green”) virtue, through daily, voluntary works of duty and obligation—from recycling drink containers and reducing packaging to taking shorter showers and purchasing green products. Practices of ecopiety evoke an idyllic harmonial model of proper relations cultivated between humans and the more-than-human earth. Much of the language used in the mediasphere to motivate practices of ecopiety speaks of “doing our part,” “saving the earth,” “shopping for change,” “buying green,” “going green,” “practicing earth care,” and “becoming more sustainable”—with exhortations often promising at the same time that “every little act,” no matter how seemingly insignificant, “all adds up.” Works of popular culture and environmental marketing campaigns are rife with messages that reassure publics that personal, individual, private acts of ecopiety are efficacious remedies to address an overwhelming array of environmental ailments, if only everyone would virtuously do his or her bit.

Like so many other aspects of contemporary social and political activism, stories of ecopiety and how to practice it reflect and perpetuate the logics of global capitalism and market ideology. As marketed in the contemporary US context, the devotional practice of ecopiety most often requires the performance of a correlative “consumopiety,” or acts of “virtuous consumption.” This book is highly attentive to correspondences drawn between ecopiety and consumopiety and probes in depth what role media and culture play in their making. As media scholars Roopali Mukherjee and Sarah Banet-Weiser point out in their research on the mediation of commodity activism, “within contemporary culture it is utterly unsurprising to participate in social activism by buying something.” Ecopiety thus thrives, this book argues, within the hospitable conditions of a depoliticized marketplace environmentalism and mediasphere that generate story after story of privatized, small-scale, voluntary, individualized acts of “green virtue” as being utterly adequate to dealing with our monumental planetary challenges. Whether circulated via the adscape, reality television, popular books, films, games, or social media, these stories explicitly or implicitly promise publics that the practice of an individualized, consumer-based ecopiety holds the key to making things on earth right again. In so doing, these stories market an imagined moral economy, in which tiny acts of voluntary personal piety, such as recycling a plastic water bottle, or purchasing a green consumer item, can be exchanged as an “offset” to justify the continuance of current consumption patterns and volume. No need to make any fundamental structural changes, implement public policy or legislation, or enforce stricter, much less existing, regulations. The trick is simply for the consumer to buy the right things, the eco-piously green things—to engage in individual simple acts to save the earth—and all will be well.

***

In archiving and analyzing sightings of ecopiety, as observed mostly in and through North American consumer marketing and mediated popular culture, this book argues that fundamentally individualized, free-market, privatized, voluntary approaches—promoted as addressing the monumental environmental challenges facing us—are not simply inadequate to the task but in some cases are counterproductive in the worst possible ways. Ecopiety, as marketed, is both too dourly restrictive in some ways and grossly facile in others. It simultaneously asks too much and expects too little, making pious actions taken on behalf of the environment grim, unappealing, onerous duties or obligations, on one hand, while they constitute superficial, perfunctory modes of practice that are by and large insignificant in terms of scale and scope of impact, on the other. In studying the concurrent dynamics of both too strict and too lenient jointly at work within certain religious institutions, sociologist Laurence Iannaccone famously labeled this combination the “worst-of-both-worlds position.” Messaging ecopiety as fun, playful, hip, sexy, and appealing, while also making it more rigorous, potent, systemic, policy linked, and effectual, is challenging but not impossible, as certain ecopiety sightings in this book illustrate. The contradictions and tensions between ideals and practices of ecopiety are explored in each chapter of this book, which also considers proposed alternatives, challenges, and creative cultural paths into the future, as conjured by various media works, practices, and narratives.

In archiving and analyzing sightings of ecopiety, as observed mostly in and through North American consumer marketing and mediated popular culture, this book argues that fundamentally individualized, free-market, privatized, voluntary approaches—promoted as addressing the monumental environmental challenges facing us—are not simply inadequate to the task but in some cases are counterproductive in the worst possible ways. Ecopiety, as marketed, is both too dourly restrictive in some ways and grossly facile in others. It simultaneously asks too much and expects too little, making pious actions taken on behalf of the environment grim, unappealing, onerous duties or obligations, on one hand, while they constitute superficial, perfunctory modes of practice that are by and large insignificant in terms of scale and scope of impact, on the other. In studying the concurrent dynamics of both too strict and too lenient jointly at work within certain religious institutions, sociologist Laurence Iannaccone famously labeled this combination the “worst-of-both-worlds position.” Messaging ecopiety as fun, playful, hip, sexy, and appealing, while also making it more rigorous, potent, systemic, policy linked, and effectual, is challenging but not impossible, as certain ecopiety sightings in this book illustrate. The contradictions and tensions between ideals and practices of ecopiety are explored in each chapter of this book, which also considers proposed alternatives, challenges, and creative cultural paths into the future, as conjured by various media works, practices, and narratives.

Sarah McFarland Taylor is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Environmental Policy and Culture at Northwestern University, where she teaches the seminar, “Media, Earth, and Making a Difference.” She holds advanced degrees in Religious Studies and Media Studies, and is the award-winning author of Ecopiety: Green Media and the Dilemma of Environmental Virtue (2019, NYU Press).