Destruction on Display: The Politics of Preservation

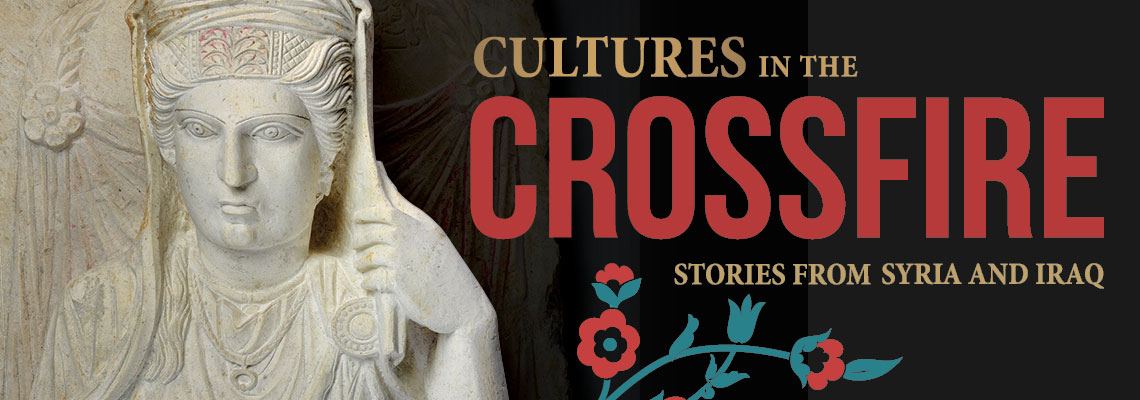

A review of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology's exhibition, “Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Syria and Iraq"

Review of “Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Syria and Iraq,” University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, April 8, 2017 through Nov. 25, 2018

The last few years have seen a remarkable increase in public activism in decolonizing the museum, especially in critiquing Western museums and their claims to ownership of artifacts from non-European cultures. As a result, some museums have planned nominal repatriation or return of some objects, while others publicly doubled down on their collections. However, the disruptive nature of questioning claims to museum collections—not to mention their financial impact—has elicited a variety of unsatisfactory responses from museums unwilling to consider them.

One of the main justifications for Western museums’ continued ownership of non-European collections, besides mostly unsubstantiated claims to legitimate provenance, has been the Western museum’s role as custodian of artifacts that would have been threatened or destroyed in their countries of origin due to instability or war. When it came to collections from Syria and Iraq, the once highly-publicized destruction wrought by ISIS provided additional justification for such ownership, now euphemistically integrated into the notion of “preservation of cultural heritage.” Thus, rather than acting as a timely response to the then-ongoing threat of ISIS, such framing enlisted ISIS’ destructive spectacle in the service of the claims of museums and other institutes to their collections.

This was the framing which fundamentally shaped the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s exhibit “Cultures in the Crossfire,” which closed in November of last year in anticipation of the Museum’s official opening of its Middle East Galleries on April 21, 2019. However, the uncritical praise of “Cultures in the Crossfire” has allowed the continuation of some of its problematic elements into the Middle East Galleries, where the narrative is essentially an uncritical love letter to the Penn archaeologists who acquired its artifacts from the so-called “Middle East,” including Syria and Iraq. It is thus crucial to revisit “Cultures in the Crossfire” to understand the heart of the Penn Museum’s narrative of its role in preserving antiquities in and from conflict areas.

***

A museum exhibit can be a place of tension, a suspension bridge for the many ideologies at work in choosing what to display and how. And it is very evident that multiple hands were at work in presenting their respective views regarding Syria and Iraq’s cultural heritage for the 2017-2018 exhibition, “Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Syria and Iraq” at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, billed as a collaboration “between the Penn Museum, the Penn Cultural Heritage Center, and artist Issam Kourbaj.”

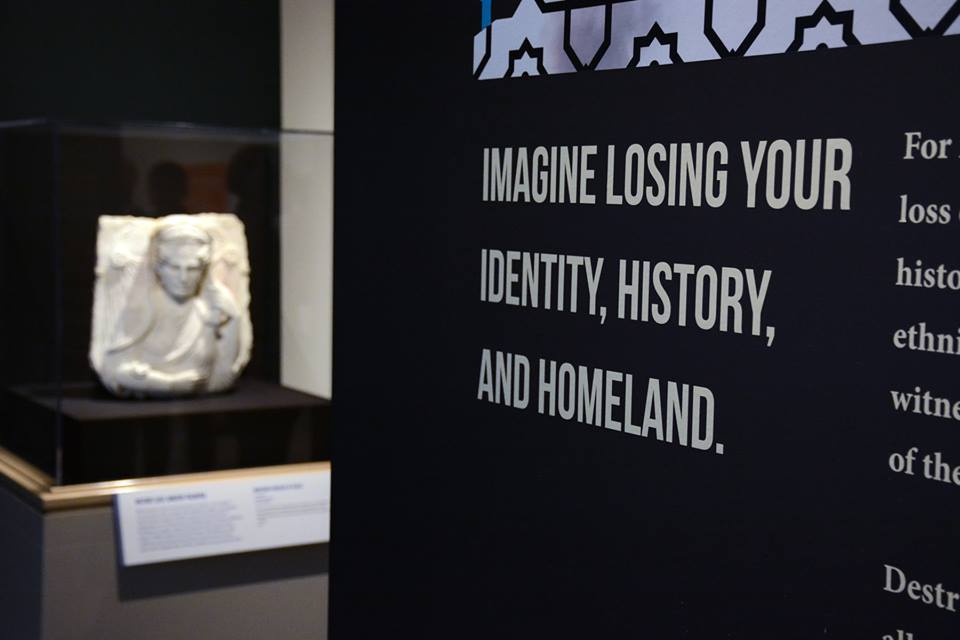

However, the exhibit’s overarching theme was evident right from its point of entry. As soon as you entered “Cultures in the Crossfire,” after having passed by the giant standing replica of the Hammurabi code stone monument and struggled with the rather heavy glass doors leading to the exhibit, the first thing you were greeted with were images of destruction – a mosque blown up, an ancient Assyrian palace ruined, a shrine destroyed – all on video loop so that they were destroyed before you over and over again.

A blurb that accompanied this display informed you that you were viewing the results of ISIS’s activities; however, larger text, elaborating on “The Conflict in Syria and Iraq,” noted that the destruction of historic sites in Syria was the responsibility of both ISIS and Bashar al-Asad’s campaign to re-assert his control as ISIS spilled over into an Iraq “destabilized by the Second Gulf War.” Despite this lonely nod to the multiplicity of actors involved in cultural destruction, the exhibit had already established its narrative that ISIS, destroyer of societies, histories, and civilizations, was an arch-villain, alone in its cruelty, and that it is from here that this museum—all museums—must pick up the pieces.

From that entry point, the exhibit directed you to the left, where another video installation, this time by contemporary Syrian-British artist Issam Kourbaj, was playing. It was a close-up of his hand lighting matches, reaching across the video screens to leave the tiny flames to die in an ashen pile on the floor. Opposite the installation hung a placard that listed the co-curators and sponsors of emergency preservation: private institutions, charitable foundations, individual archaeologists, and of course, the Penn Museum and Penn Cultural Heritage Center. It also contained a long column of acknowledgments filled with the various cultural and government agencies of the US government and the coalition forces that had been fighting against ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

As you continued walking, you would have passed white mortuary statues from Palmyra dated to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Across from them, an accompanying BBC documentary, “Ancient Worlds,” patiently waited to inform you of the historic import of these artifacts for “world civilization.” Beside it was a mural-size photo of Syrians in the bustling Damascus market of Souq al-Hamidiyyeh, next to the exhibit’s text proclaiming the rich religious and ethnic diversity of Syria: “Arabs, Kurds, Arameans, Assyrians, Armenians, Circassians, Turkmens, Sunnis, Shias, Druze, Ismailis, Christians, Jews, and Yazidis. All call Iraq and Syria home.” (You might have chosen to ignore the bizarre distinction between Ismailis and “Shias.”) But even this placard’s small attempt at moving beyond orientalist notions of religion in the Middle East being particularly entrenched in violence—a thinly veiled allusion to Islam—was contradicted by the next placard, which grandly proclaimed orientalist truisms such as “Religion occupies a prominent position in Middle Eastern societies. It has been a socio-political force deeply rooted in history,” as if this somehow set apart Middle Eastern societies from any other society in the history of the world. What this statement did, however, was set up the “Middle East”—itself an amorphous concept that the exhibit never problematizes—as the polar opposite of Western secularism and “modernity,” a typical orientalist trope that has historically justified colonialist expansion into these areas, and more recently, military invasion and “rebuilding.”

While the exhibit noted that “every individual, family, tribe, community, and nation claims a multi-layered identity from this diverse heritage,” it provided little context as to the overlap between ethnic and religious identities—let alone political and historical affiliations—that would have given visitors a more thorough understanding of the impact of war and the subsequent exacerbation of its violence in these two countries. The disjointedness of what the thematic placards proclaimed and what was actually on display was consistent throughout the exhibit.

***

University museums should be at the forefront of questioning the orientalist histories of their collections, not reinforcing them. In addition to rethinking the museum’s relationship to orientalism, colonialism, and neo-imperialism in light of the context of preservation work, we must also ask: What kind of history is the “West” preserving, and why?

Although this exhibit took great pains to show a different side of the Middle East to American audiences, brief references to the diversity of cultural traditions and their historical coexistence still strained against an insistence on religion as the sole or primary marker of identity.

On the one hand, the curators emphasized the nature of war and its effect on the vulnerable populations of these two countries, their living memories as well as their cultural heritage. There were placards throughout showing how Syrians and Iraqis, including children, were proudly and actively engaged in preserving, restoring, and maintaining their historical sites.

On the other hand, these images did not disrupt the persistent Western gaze which has regarded such areas as places merely waiting to relinquish their ancient artifacts to safekeeping by Western guardians. This tension was most evident in the Daily Life portion of the exhibit, which purported to show how “cultural traditions span generations” and domestic objects “tell the story of how people live every day,” even as its placard euphemistically noted that such activities were disrupted when “families separate or people are removed from their homelands.”

The exhibit then presented a few artifacts—a calligraphic serving bowl, a ladle, and a copper frying pan—whose periods of production ranged from 2400 BCE to the 9th century CE, a thematic grouping that only drove home the orientalist image of an unevolving Middle East. Another case contained toys and amulets dating from before 200 CE, as well as another lamp, a sandstone mold for spearheads and chisels, and decorative wall tiles that together covered a range from 2400 BCE to the 16th century CE, a span of nearly 4000 years. What we were meant to understand from this in the context of displacement and war was hard to assess—People have used cookware and lamps throughout history? The Middle East is an unchanging place?—other than the fact that the Penn Museum owns these objects.

The artifacts themselves were also presented in a vacuum: the object, its provenance, and its estimated period of production were briefly described, without any attempt at contextualizing a modern collective Iraqi or Syrian understanding of their place in cultural memory. Barring the photo of the crowds in the Damascus market, there was no real indication of what daily life in Syria was like before the war.

It was clear through the objects on display that the exhibit found itself most comfortable at the points most distant from the daily realities of colonialism and neo-imperialism, such as its presentation of ancient Hellenic and Byzantine artifacts and medieval Arabic manuscripts on science, philosophy, and music. At these points the exhibit provided brief glimpses into ongoing local efforts in the preservation of historic sites in Syria and Iraq. Kourbaj’s art—such as the plaster casts of refugee children’s clothes overlooking an Iraqi tombstone on display, dated between the 1st and 5th centuries CE—was interspersed throughout to remind attendees of the current violence and egregious loss of life.

However, no amount of inclusion of Kourbaj’s art throughout the exhibit mitigated the fact that it seemed to sit on top of, rather than inform, the rest of the exhibit. Kourbaj’s “Dark Water, Burning World,” a modern recreation of 5th century BCE Syrian sea vessels made from matchsticks and recycled bicycle parts, served as a powerful commentary on the changed relationship of Syrians to the Mediterranean as refugees. However, the artifacts used as the point of reference, held by the Fitzwilliam Museum at the University of Cambridge, provided their own irony: Kourbaj’s access to his cultural heritage is mediated through a European museum and its own claim over them.

Dark Water, Burning World (Issam Kourbaj’s, 2016)

The “Cultures in the Crossfire” exhibit, furthermore, was severely restricted by its own collection on display, which asserted the value of Syrian and Iraqi artifacts only to the extent that they conformed to the idea of contributing to “Western civilization.” This persistent idea places Westerners as the natural and exclusive heirs to “classical” civilization, and posits a linear progression from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to Greece and Rome, whose ideas were then filtered through the Christian elites of northwest Europe (known generically as the “Medieval” period). Islamic civilization is thus understood as only a brief interlude in this trajectory, in which, as historian of Islam Marshall Hodgson put it, it was “permitted to hold the torch of science, which properly belonged to the West, until the West was ready to take it over and carry it forward.”

The exhibit ultimately reflected the unexamined notion of the universalism of “world civilizations,” justifying Western claims on pre-Islamic Middle Eastern heritage: if certain cultural artifacts can be said to belong to the world, then anyone has the right to claim them. This depiction is most explicitly reflected at the very beginning of the exhibit where Andre Parrot, French archaeologist and former director of the Louvre, was quoted as saying “Every person has two homelands…His own, and Syria.” What the exhibit presented as a love paean to Syria belied the imperialist claim to the dismemberment and appropriation of pre-Islamic Middle Eastern history, even as its current populations are patronizingly allowed to be associated with their cultural artifacts kept abroad. It was also here where we come across the problem of the museum itself: the irony of an exhibit that lamented physical destruction without questioning the framework of antiquities dealing and museum collection that fuels looting, another major form of cultural destruction, or the ongoing US and coalition military strikes that regularly destroyed historical sites in Syria and Iraq.

Between the emphases on ancient history, modern artistic interpretation, and occasional reference to the humanitarian crisis, at no point did the exhibit make reference to any of the history leading up to the creation of ISIS. There was no reference to the periods of British and French colonialism that led to the rise of mandates (later to be carved out as nation-states), of expedient boundaries drawn and rulers appointed as well as overthrown, military coups, or dictatorships. While it is true that an exhibit cannot be all things to all people, the lack of historical context remained a glaring omission that reinforced the notion of the Middle East as a monolithic, unchanging, and especially violent place.

In many ways, the problems that underlay this exhibit can be traced back to its funding through the US government, whereby critique—or even mention—of US military aggressions in the region ostensibly could have no place. Taken together, the art installations and the exhibit’s collection created an abrupt before-and-after panorama in which the destruction unleashed by ISIS was the climax, and in which US aggression, as well as civil war, were conspicuously absent. This type of presentation engaged in a malicious type of politics, depicting ongoing wars as taking place solely between Good Muslims and Bad Muslims, in which Good Muslims are represented by those who participate in the projects of preservation (as prioritized by coalition forces), and Bad Muslims by ISIS.

Even as the exhibit’s text claimed that “this war is a blip in the history of the Middle East,” the almost complete absence of any reference to war waged by external forces, and in the case of Iraq, actual foreign invasion, promoted the idea that ISIS spontaneously emerged as a symptom of the violence inherent to the Middle East.

This depiction is further problematic because ISIS was not the only or even primary force involved in the destruction of Syria and Iraq’s cultural heritage, although it was the one most adept at shaping its propaganda through visual imagery and media. The museum’s laser focus on ISIS as the end-all and be-all of destruction of cultural heritage worked to not only render US military intervention as non-destructive, but to further vindicate it, since US military assaults since 2014 had been justified by the threat of ISIS. This concentration on ISIS was complicit in the very narrative that ISIS itself propagated through its videos of destruction, like the ones on loop at the beginning of the exhibit.

As Syria not only continues to suffer from violence, the question is not one of outside military intervention, but rather, of how the realities of such intervention become obscured regarding basic facts about who the US is fighting and what kinds of destruction the US military, its allies, and its enemies, are perpetrating —both in terms of human lives as well as physical sites.

It may seem harsh to derive such an analysis from what is otherwise a lofty goal—sponsoring emergency preservation work in Syria and Iraq through collaboration between American and local teams, and educating the American public through an exhibit. Indeed, preservation work can be an immediate necessity. But the exhibit made a choice in its depiction of such destruction—a choice that might have been considered prudently neutral, but which was, in fact, deeply political.

***

Much like the act of destruction and rebuilding, it is easier to break down through critique than to build up. The exhibit occasionally put forth balanced counter-responses to their otherwise typical, almost classical selection of manuscripts, mortuary busts, and other ancient archaeological artifacts. The choice to display a beautifully decorated Kurdish doll in “traditional” dress did double duty as representation of women’s handiwork as well as the lives of children. This rare intervention was an important reminder of the prioritization of men’s cultural production in the narrative of history and art, including the exhibit’s own selection of a male contemporary artist.

Another important, more fundamental intervention was a small kiosk of audio recordings, tucked away in a “House of Wisdom” wall panel, which invited you to listen to Syrian and Iraqi songs and poetry, as well as the call to prayer of the now severely-damaged Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Two selections gave a glimpse of modern Syrians’ and Iraqis’ emotional and cultural connections to each other: Syrian Nizar Qabbani’s poem to his Iraqi wife, Bilqis, and Iraqi poet Muzaffar al-Nawwab’s “A Poem to Damascus.” It was a shame that this kiosk was so easily overlooked, as it is the more intangible cultural artifacts, like poetry, that give a stronger sense of modern Syrians and Iraqis as real living, breathing people rather than mere artifacts themselves. At least their humanity is preserved in these selected verses by Amineh Abou Kerech, a Syrian refugee who won the British Betjeman poetry prize as a 13-year-old in 2017:

I am from Syria

From a land where people pick up a discarded piece of bread

So that it does not get trampled on

From a place where a mother teaches her son not to step on an ant at the end of the day.

From a place where a teenager hides his cigarette from his old brother out of respect.

From a place where old ladies would water jasmine trees at dawn.

From the neighbours’ coffee in the morning

From: after you, aunt; as you wish, uncle; with pleasure, sister…

From a place which endured, which waited, which is still waiting for relief.

***

Raha Rafii received her PhD (2019) in medieval Islamic history and law from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Pennsylvania. She is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the University of Exeter.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.