Crucifying the Musical Christ

The Politics of Jesus’ Death in "Godspell" and "Jesus Christ Superstar"

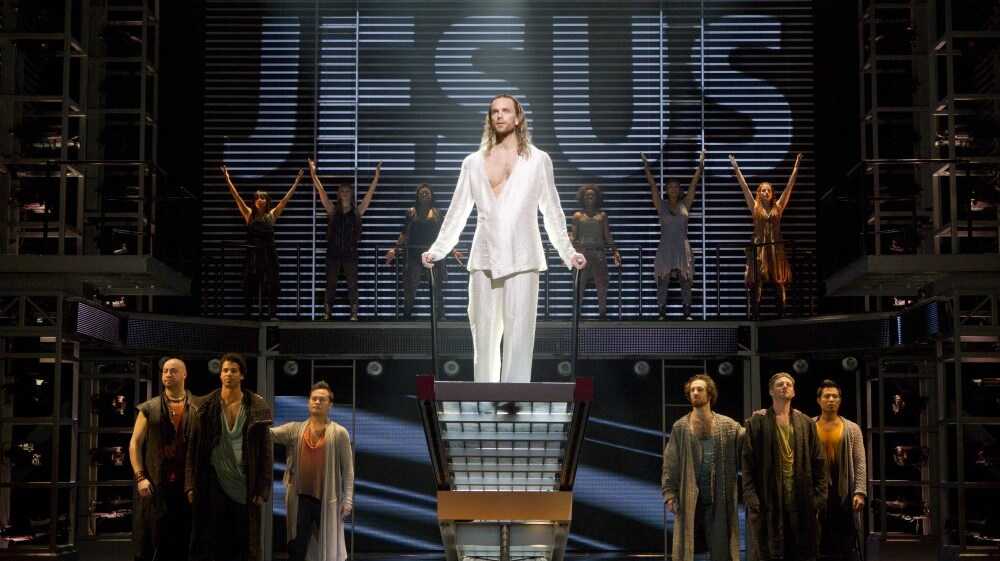

(Scene from Jesus Christ Superstar. Image source: Austin Chronicle)

Who killed Jesus? And why? Whatever historians make of Jesus’ life and however they explain the endurance of a movement bearing his name, one thing seems clear: Jesus was killed. But that passive construction conceals a controversy that began in the first century and continues today. Two millennia after one Jewish author blamed his own people for the crucifixion of Jesus by Roman soldiers (1 Thess 2:15), the question of how best to describe the events precipitating Jesus’ death remains historically, theologically, and ethically controversial.

Two Broadway musicals-turned-Blockbuster films, Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar, represent profoundly different approaches to this problem. In fact, the portraits of Jesus in these musicals reflect two conflicting explanations for Jesus’ execution, each associated with a different school of thought in twentieth-century debates over the historical Jesus. These two schools offer importantly different descriptions of Jesus’ message, his relationship with fellow Jews, and the reasons for his execution. But, as the continued popularity of these musicals illustrates, these contrasting conceptions of Jesus are not confined to the halls of the academy. Godspell and Superstar represent two distinct images of Jesus in the popular imagination.

Dramatizations of Jesus’ death are nothing new. Since antiquity, Christians have recreated scenes from the gospels, freely expanded the dialogue between Biblical characters, and otherwise acted out their sacred history. Unfortunately, these dramatizations have long contributed to Christian anti-Judaism and its racialized derivative, antisemitism. From Syriac Dialogue Poetry to Medieval Mysteries, Christian elaborations of the gospel story have long demonized the Jewish people. Dramatizations of Jesus’ death, often called Passion Plays, incited crowds of European Christians to commit acts of violence against their Jewish neighbors. Hitler himself endorsed the Oberammergau Passion Play specifically for its representation of Jews contriving Jesus’ execution.

Can the story of Jesus be told without perpetuating the same anti-Jewish sentiments that motivated millennia of violence and discrimination? Although neither Godspell nor Superstar represent a solution to this complex conundrum, the differences between their representation of the first century political situation may point us toward more responsible ways of describing Jesus’ death.

Jesus Takes the Stage

Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar are, in many ways, similar. Both musicals made their on-stage debut in 1971. Both are (mostly) sung-through, containing little dialogue that isn’t set to song. Both appeared on film in 1973. Both movies feature color-blind casting. Both were influenced by the “hippie” counter-culture of the ‘60s and ‘70s. And both generated controversy for not clearly depicting Jesus’ resurrection.

Despite these similarities, however, their representations of Jesus could hardly be more different. The Jesus of Superstar is somber, easily angered, and unsure. In the song “Gethsemane,” for instance, Jesus sings,

“I have changed.

I’m not as sure, as when we started.

Then, I was inspired.

Now, I’m sad and tired.”

Jesus in Superstar is a man of sorrows, misunderstood by his closest followers and, by the end, both physically and psychologically tortured.

In contrast, the Jesus of Godspell has a smile plastered across his face for almost the entire musical. He wears literal clown makeup. Jesus is engaged in constant play, and his teachings are littered with laugh lines. For instance, Jesus’ critique of hypocrisy, “how can you take the speck of sawdust out of your brother’s eye, when all the time there’s this great plank in your own?” concludes with a slide-whistle and laughter.

However, the differences between these two portrayals of Jesus are not limited to personality traits. The musicals offer drastically different accounts of Jesus’ teachings, first-century political realities, and the motives of Jesus’ opponents. These choices in adaptation constitute to two different explanations for the execution of Jesus. And although there is plenty to criticize about the representation of Judaism in both musicals, the account of Jesus’ death in Superstar does not depend on the demonization of the Jewish people.

The Philosopher Jesus of Godspell

Godspell, written by John-Michael Tebalak and Stephen Schwartz, begins with a half-sung half-spoken number, “Tower of Babble.” The opening song (cut from the David Greene’s film adaptation) features a series of philosophers—including Socrates, Nietzsche, and Sartre—each espousing their own ideology. These philosophical soliloquies descend into chaotic babble until the Baptist’s clarion “prepare ye the way of the Lord” cuts through the noise. As such, this opening song frames Jesus as an answer to (or, perhaps, the culmination of) the history of philosophy. The Jesus of Godspell is a philosopher —a teacher of wisdom.

But what wisdom does Jesus offer? Godspell samples an array of parables and sermons from throughout the gospels. But its overarching message is clear: “Come sing about love // Come sing about love” runs the refrain of “We Beseech Thee.” The chorus responds, “Love! Love! Love! Love!” Elsewhere, Jesus paraphrases the gospels: “You have learned that they were told, ‘Love your neighbor, hate your enemy.’ But what I tell you is this… Love, love, love, love your enemies.” The stage directions, then, prescribe a “general love fest,” with the disciples jumping up and down repeating “love, love, love, love.”

(Scene from Godspell. Image source: Arts & Faith Magazine)

So too Godspell’s Jesus espouses unflagging joy. John-Michael Tebalak said that reading the gospels helped him find “what [he] wanted to portray on stage… Joy!” Early in the musical, Jesus’ clownish smile spreads to his grinning disciples and each receive some of Jesus’ face paint. In the midst of “All Good Gifts,” Jesus instructs his followers to “rejoice in hope.” Stage directions make repeated reference to the “joy” of Jesus and his followers, including the conclusion that Jesus’ disciples “leave with a joyful determination.”

Who could oppose such a teacher of love and joy? And why? In the film, Jesus’ opposition appears as a giant, robotic caricature of a rabbi. After a brief back-and-forth cribbed from the gospels, Jesus begins to sing “Alas for You.”

“Alas, alas for you,

Lawyers and pharisees

Hypocrites that you be”

According to Godspell, it is sheer hypocrisy that motivates Jewish opposition to Jesus. There is no trace of substantive disagreement or wider political context. This Jewish caricature resists Jesus and his message of love simply because it is vicious.

Following this scene, there is little evidence of Jewish opposition to Jesus until Jesus’ crucifixion. Here, the actor who plays both John the Baptist and Judas hangs Jesus from a chain-link fence in cruciform. As he’s hanging, Jesus quotes an assortment of verses, concluding with a line from the trial before the Jewish High Priest: “I sat teaching in the synagogue and you didn’t come after me then” (John 18:20). Jesus’ reference to the synagogue alongside his direct address, “you didn’t come after me,” suggest that Jesus is literally crucified by his Jewish adversaries. There is no hint of Rome’s involvement.

Elsewhere, the musical contains only one reference to the occupying Roman power. This solitary allusion to the Roman occupation of Judea is Jesus’ approval of paying taxes to Caesar. Apart from this one line, however, Jesus’ ministry takes place in a socio-political vacuum. To the extent that he comments on any social realities, Godspell’s Jesus is decidedly quietist. The song “All for the Best” depicts Jesus consoling the poor and downtrodden because “when you get to heaven you’ll be blessed.” The song acknowledges that some enjoy opulent wealth, while others struggle to get by. But, after repeating the promise of heavenly reward, the number resolves, “someone’s got to be oppressed!”

Similarly, the song “God Save the People” explicitly denies any social or political dimension to God’s promised salvation.

“When wilt thou save the people?

Oh God of mercy when?

The people, Lord, the people,

Not thrones and crowns, but men!”

Jesus’ hope for individual salvation contains nothing to threaten “thrones and crowns.” Absent from Godspell is any apocalyptic proclamation of impending judgment. There is little talk of a coming kingdom. The Jesus of Godspell is decidedly apolitical. Nothing about Godspell’s Jesus would attract Rome’s ire.

But the story needs to end in crucifixion. Tebelak’s apolitical preacher of brotherly love is persecuted, therefore, by a Jewish caricature motivated by nothing more than malice. The Jewish people even replace the Roman soldiers as directly responsible for the crucifixion. As such, Godspell—and especially its film adaptation—continues a long and lamentable Christian tradition of demonizing Jews, amplifying their role in Jesus’ death, and erasing any relevant political context.

The basic contours of Godspell’s Jesus are strikingly similar to one of the two models for understanding the historical Jesus in the late 20th century: the Sapiential (i.e. philosopher) Jesus. Bible scholars, including John Dominic Crossan, Marcus Borg, and members of the Jesus Seminar, popularized an image of Jesus as a teacher of wisdom who, like the cynic philosophers of classical antiquity, dropped out of society to form a community based on radical kindness and generosity. The apocalyptic prophecies attributed to Jesus in the gospels, these scholars concluded, did not reflect the teaching of the historical Jesus. Instead, Jesus espoused a kingdom of loving kindness. Admittedly, the Sapiential Jesus of Crossan and Borg is more socially conscious than the portrayal in Godspell but, like Tebelak’s Jesus, he preaches compassion, communalism, and charity.

Just as the Jesus of Godspell needed a vicious caricature of Judaism to oppose his message of love and joy, so too this portrait of Jesus as a philosopher sets Jewish legalism against Jesus’ politics of compassion. On this model, Jewish law becomes a misogynistic, xenophobic, and oppressive regime to provide a foil for Jesus’ proclamation of acceptance and inclusivity. This account of Jesus’ death does not entirely erase Rome, but reimagines it as an instrument of the Jewish elite to suppress Jesus’ message of love and kindness. There are important differences, but Godspell delivers something meaningfully similar to the Sapiential Jesus of scholarly imagination.

The Apocalyptic Jesus of Jesus Christ Superstar

Jesus Christ Superstar, written by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, offers a very different account of the events leading up to Jesus’ death. The opening number, “Heaven on their Minds,” already establishes a distinct setting for Jesus’ life. Judas, standing apart from the other disciples, sings a warning to Jesus.

“Listen, Jesus, do you care for your race?

Don’t you see we must keep in our place?

We are occupied; have you forgotten how put down we are?

I am frightened by the crowd.

For we are getting much too loud.

And they’ll crush us if we go too far.”

This song introduces Jesus as the source of a conflict. But this conflict is not between Jesus and his fellow Jews; it is between the Jews (including Jesus) and the occupying Roman army. “We are occupied,” says Judas, and our occupiers are liable to respond to crowds with violence. What tension exists between Judas and Jesus is motivated by the former’s care for their shared people.

Norman Jewison’s film adaptation of Superstar, then, cuts away to Roman soldiers patrolling the Judean countryside. Jesus’ disciples, hidden in a cavern beneath the soldiers’ feet, sing, “When do we ride into Jerusalem?” over and over again. A subsequent number, “Simon Zealotes,” also sung by Jesus’ disciples, removes any ambiguity about their meaning.

“Christ, what more do you need to convince you

That you’ve made it, and you’re easily as strong

As the filth from Rome who rape our country,

And who’ve terrorized our people for so long.

[…]

Keep them yelling their devotion,

But add a touch of hate at Rome.

You will rise to a greater power.

We will win ourselves a home.”

These songs make clear what Jesus’ followers expect from him: Judea’s deliverance from Roman occupation.

The musical’s third song, composed especially for the film, offers our first glimpse of Jewish leadership. Two Chief Priests, Caiaphas and Annas, deliberate over how to respond to Jesus. “He doesn’t really matter,” contends Annas. But Caiaphas disagrees: “Jesus is important” and might “start […] a major war.” Caiaphas, then, explains that Jesus is not “just another scripture thumping hack from Galilea.”

“The difference is they call him King,

The difference frightens me!

What about the Romans?

When they see King Jesus crowned,

Do you think they’ll stand around,

Cheering, and applauding?

What about our people?”

Like Judas and the other disciples, Caiaphas sees Jesus and the Roman state on a collision course. Judas, the disciples, and the Jewish leadership all act out of concern for their shared people. Superstar depicts intra-Jewish conflict along multiple axes, but the threat of Rome is its occasion.

(Scene from Jesus Christ Superstar. Image source: NPR)

How does Superstar portray Jesus himself? The musical begins in the final week of Jesus’ life, so the preaching that occupies most of Godspell occurs before the beginning of Superstar’s script. The Jesus who appears on stage/screen reacts to the aftermath of his implied preaching career but says very little of substance. Nevertheless, the three songs already discussed give us a reasonable sense of Jesus’ message. Jesus, these songs report, spoke of a kingdom in a way that his admirers and opponents alike interpreted as implying the liberation of Judea.

Pressed to clarify such statements by Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, in “Pilate and Christ,” Jesus prevaricates.

PILATE

We all know that you are news,

But are you king?

King of the Jews?

JESUS

Your words, not mine.

And again in “Trial before Pilate.”

PILATE

Listen King of the Jews,

Where is your kingdom?

Look at me. Am I a Jew?

JESUS

I have no kingdom.

In this world, I’m through.

There may be a kingdom for me somewhere.

If you only knew.

PILATE

Then you are a king?

JESUS

It’s you that say I am.

Jesus’s statements are ambiguous, but he refuses to mollify the Roman governor’s concerns by disavowing a political interpretation of his message. Jesus claims to be some kind of king.

Among New Testament scholars, the main alternative to the Sapiential portrait of Jesus is the Apocalyptic Jesus. This school of thought—most famously advocated by Albert Schweitzer but championed at the end of the 20th century by the likes of E.P. Sanders and Dale Allison—imagines Jesus as a prophet of God’s impending judgment. Jesus’ talk of a coming kingdom refers to the imminent action of God to set the world right. Jesus, then, claimed for himself and his followers some important role in that kingdom—perhaps the “thrones and crowns” disavowed by the Jesus of Godspell. Superstar presupposes something very much like Schweitzer’s image of Jesus as a prophet of the coming apocalypse.

Importantly, most apocalyptic interpreters don’t believe Jesus was mounting a conventional, armed revolt against Rome. The gospels suggest, rather, non-violent resistance with the expectation (shared by other first century Jews) of divine intervention. The Jesus of Superstar reflects this same commitment to non-violence, responding “Why are you obsessed with fighting?” to his disciples’ call for a march on Jerusalem.

Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Superstar is hardly innocent of anti-Jewish tropes. The original stage production dressed Annas and Caiaphas as gargoyles—a literal demonization of the Jewish leaders. In the film, they don black robes and ostentatious hats. Along similar lines, the diverse Jewish sects with their distinctive ideological positions found in the gospels are collapsed into a single amorphous but markedly Jewish opposition. As reviewers have long noted, Superstar is not a guiding light for responsible depictions of Jews or Judaism.

Where Superstar shines, however, is its depiction of the events precipitating Jesus’ death as arising out of the political realities of first-century Judea. It was, in the end, the Romans who crucified Jesus. One can acknowledge the presence of intra-Jewish conflict surrounding his death without decrying Judaism or demonizing Jewish people. Superstar even gives Judas and the Jewish leaders sympathetic motives —a concern for the safety of the Jewish people— derived from John 11:50. The Apocalyptic Jesus of Superstar is a first-century Jew engaged in controversy with fellow Jews but ultimately executed by their common oppressors, the imperial Roman state.

Jesus Exists Stage Left

The Apocalyptic Jesus of Superstar and the Sapiential Jesus of Godspell represent two different portraits of the preacher from Galilea. Neither musical is above reproach in their portrayals of ancient Jews and Judaism. But while Godspell vilifies the Jewish leaders and amplifies Jewish culpability for Jesus’ death, Superstar depicts Jesus in a way that explains his execution by the Roman state and gives sympathetic motives to his Jewish opposition. Artists as well as historians have an ethical obligation to avoid perpetuating the same anti-Jewish narratives that motivated centuries of very real violence against the Jewish people. Maybe these fifty-year-old musicals are due for a re-write?

Or maybe, even better, the time has come for a new Jesus musical that refuses to reinforce Christian antisemitism.

Ian N Mills is Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics and Religious Studies at Hamilton College. Ian is a scholar of early Christianity and a co-host of the New Testament Review podcast.