Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism

Excerpt from Emily Ogden's new book, Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism (Chicago, 2018).

Secularity aspires not to banish enchantment, but to manage it. This managerial effort runs aground, giving rise to a more diverse set of relations between would-be moderns and the people they call credulous. That’s the two-part proposal of Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism.

The book’s particular subject is mesmerism, a precursor to hypnosis that was popular in the US from the 1830s to the 1850s. What interests me about mesmerism is that practitioners used disenchanted means to produce enchanted states. In the careful terms of bureaucratic rationality, mesmerists outlined how to perform mesmerizing gestures. Yet the trance states they induced were, by their own account, exactly the same as the ones priests and magicians had long elicited from their so-called credulous subjects, whether at Delphi, among Lapland shamans, or in Kentucky revivals. Mesmerists hoped that even magic could be tamed and re-deployed for use within a disenchanted framework. But magic exceeded its frame. The book demonstrates how mesmerism’s secular affects and projects both needed enchantment and came to resemble it.

Credulity traces mesmerism’s rise in America, from its introduction by a Guadeloupean slaveholder to its use as a means of personality analysis to its triumph as a mass spectacle.[1] Without dissolving the difference between enchanted and disenchanted attitudes, Credulity shows how much, through long adversarial conversation, they end up taking from each other. As the coda concludes, “there is no special reason why you would be freer from your idol when your idol is your freedom of choice than when it is your little wooden god.”

Excerpted below are the first few pages of the book’s introduction.

–Emily Ogden, introduction to Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism

***

Out on Credulity! ‘t would swallow whole

A rabbit belly’d elephant foal

– Laughton Osborn, The Vision of Rubeta (1838)[2]

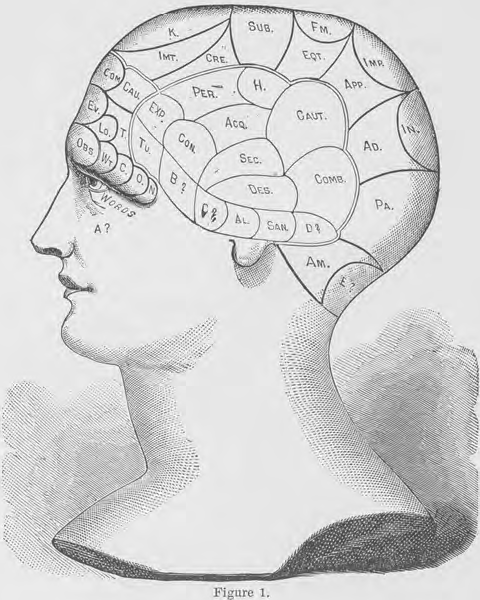

J. Stanley Grimes, an American mesmerist, announced in 1845 that he had discovered the organ of the brain that accounted for enchantment. “Credenciveness” governed religious faith and overall gullibility; it accounted for why one might enter an apparently magical trance, believe in false gods, or fall for a confidence game (Fig. 1). Too much credenciveness meant “superstition, credulity.”[3] Grimes explained that “prophets and seers and soothsayers of ancient times” had possessed a secret technique for heightening the organ’s activity; their knowledge allowed them to propagate such lamentable errors as the Delphic oracles and the Shaker prophecies and gave them “unbounded sway over the minds of the ignorant masses.”[4] His next step was not, however, the one we tend to expect of Enlightenment’s heirs: he had no interest in stamping out either credenciveness or the techniques that had stimulated it. On the contrary, he wanted to perpetuate those techniques. He proposed first to explain the false priests’ chicanery and then to appropriate it, redirecting their occult gestures toward new rational ends. He proposed, in a word, to practice mesmerism.

Fig. 1. Bust showing the organ of Credenciveness. In J. Stanley Grimes, The Mysteries of the Head and Heart Explained (Chicago: W. B. Keen, Cooke, 1875), p. [1]. Credenciveness is marked “eRE’ and appears above the temple, toward the crown of the head. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Mesmerists, who were active in the United States between 1836 and the Civil War (1861–1865), offered an applied science of excessive belief, or credulity. Not all practitioners tied credulity to a phrenological organ, but most shared Grimes’s conviction that when they entranced their subjects with precisely choreographed gestures, thus inducing a suite of phenomena including delusion, thrall, and prophetic knowledge, they were updating false religion for modern use. Employed secretly, the mesmeric gestures abetted Delphic frauds. Employed openly and rationally, the same gestures served enlightened ends. Was the mesmerized subject fantastically obedient? Then mesmerism could help discipline workers. Was the subject clairvoyant? Then he could speedily communicate the price of cotton from north to south. Could the subject read minds? Her insight might aid in educating young people. All of these uses were proposed; the first and last were attempted. If one imagines that a person can be either a debunker or a practitioner of the occult, but not both at once, mesmerism poses a problem. Mesmerists did not believe in magic, but they did believe in the utility of others’ belief. They were not enchanted themselves, but they were eager to use the enchantment of others.

“To enchant” has long been an ambivalent verb in English; it means to delight, and also to delude; to enrapture, and also to rape; to spellbind figuratively, and also to spellbind literally. When disenchantment was used to translate Entzauberung (literally, demagification) in Max Weber’s foundational account, “Science as a Vocation,” enchantment became the term for that state of the world before modernity when one is in awe but in error, like the propitiating savage. Enchantment became a periodizing word, that is: the world used to be enchanted, and now it is not. Whatever the shortcomings of this translation,[5] it does preserve Weber’s own ambivalence about the transition he described. The world is enchanted when “the savage,” deluded about reality, has “recourse to magical means in order to master or implore the spirits.”[6] When the world is disenchanted, by contrast, everything is “in principle” manipulable through “technical means and calculations,” and one can live bravely, honestly, but a little sadly in the face of this knowledge.[7]

In recent years, and to some extent as an attempted correction of Weber, scholars have taken a celebratory attitude toward enchantment. States of awe, and even magical practices, can persist in modernity, despite the best efforts of skeptics and disillusionment artists, and we are lucky—from an ethical, aesthetic, or political standpoint—that they do persist. As philosophers have sought ethical sources in wonder;[8] as literary critics have looked to aesthetic transports for new (or old) ways of reading raptly;[9] and as historians have drawn our serious attention to the occult,[10] the tone has been distinctly optimistic.[11] The darker aspects of enchantment, which have belonged to that term for as long as it has been in use, appear not as its real features but as the paranoid overlay bequeathed to us by some combination of Weber and the Enlightenment. If we want to see enchantment accurately, on this view, we have to stop listening to the shrill warnings against it. Heeding these warnings will hinder us in our efforts; it will distort our understanding of what enchantment is.

I take a different view. Where recent work on enchantment has accentuated the positive, this book accentuates the negative. It recognizes that practitioners of modern enchantment may look like Grimes: contemptuous of the manipulated “masses,” yet more than willing to try a little manipulation themselves. The book’s tendency is not reactionary; the point is not to return to decrying enchantment. The point instead is to ask what those who decried enchantment were actually doing with it in practice. How were they using it? Like New York literatus Laughton Osborn, skeptics exclaimed, “Out on Credulity!”[12] Like David Reese, the author of Humbugs of NewYork (1838), they deplored “such sublimated folly, such double distilled nonsense, as popular credulity is perpetually swallowing.”[13] But meanwhile many of them were busily seeking employment for the very thing they spurned, as Grimes was. This study shows that the skeptic of this period sought to manage enchantment, not to suppress it. To confine, explain, and redeploy primitive religious power: these were the quintessential aspirations not just of mesmerists in particular but also of antebellum secularism in general. Skeptics’ characterization of enchantment as the product of credulity cannot be ruled out of court as a secular prejudice, as recent scholarship has sometimes been inclined to do. Credulity is where critical thought about modern enchantment must begin.

***

[1] If you think that sounds relevant to our present moment, you’re right: “Donald Trump, Mesmerist,” New York Times, August 4, 2018.

[2] Laughton Osborn, The Vision of Rubeta (Boston: Weeks, Jordan, 1838), 68.

[3] J. Stanley Grimes, Etherology; or, The Philosophy of Mesmerism and Phrenology (New

York: Saxton & Miles, 1845), 169.

[4] Ibid., 43.

[5] Jane Bennett, The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 57. On translation questions, see Michael Warner’s review of John Modern’s Secularism in Antebellum America: “Was Antebellum America Secular?” The Immanent Frame (blog), October 2, 2012, http://blogs.ssrc.org/tif/2012/10/02/was-antebellum-america-secular/.

[6] Max Weber, “Science as a Vocation,” in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, trans. and ed. H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (New York: Routledge, 1948), 139.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Bennett, Enchantment of Modern Life, 3–4, 12–13, 131–58.

[9] Michael Saler, As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Real ity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 14, 57; Rita Felski, Uses of Literature (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 51–76.

[10] Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of NineteenthCentury America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008); Alex Owen, The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

[11] On the cleansing of delusion from modern enchantment, see David Walker, “The Humbug in American Religion: Ritual Theories of Nineteenth-Century Spiritualism,” Re ligion and American Culture 23, no. 1 (2013): 30–74, esp. 57n6, and Tracy Fessenden, “The Problem of the Postsecular,” in “American Literatures/American Religions,” ed. Jonathan Ebel and Justine S. Murison, special issue, American Literary History 26, no. 1 (2014): 154.

[12] Osborn, Vision of Rubeta, 68.

[13] David Reese, Humbugs of NewYork: Being a Remonstrance against Popular Delusion (Boston: Weeks, Jordan, 1838), 15.

***

Emily Ogden (@ENOgden) is assistant professor of English at the University of Virginia and the author of Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism (Chicago, 2018). She has written for The New York Times, Critical Inquiry, Lapham’s Quarterly Online, American Literature, J19, Public Books, and Early American Literature. See www.emilyogden.net for most publications.

***

Reprinted with permission from Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism by Emily Ogden, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2018 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.