Consuming Religion

George González reviews Kathryn Lofton's new book Consuming Religion

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – MARCH 5: Serena Williams of the United States during the Tie Break Tens Tennis Tournament at Madison Square Garden on March 5, 2018 New York City. (Photo by Tim Clayton/Corbis via Getty Images)

I am a huge tennis fan. Most of all, I prefer to watch long baseline rallies and carefully constructed points. I can also appreciate the work of the net rushers who pounce on balls that land well short of the baseline and put the volley away for a winner. Serena Williams is, without a doubt, the greatest tennis player of all time. I, like many a fan, have experienced the thrill of watching her dominate since she was a kid in the late 90s. Now her devotees get to share in the thrill of watching Williams make her comeback after having given birth to her daughter with Reddit co-founder, Alexis Ohanian, only this past September.

Over the years, the public has taken a constant interest in Williams’ romantic life, following her relationships with famous musicians and sports stars. Now we dutifully attend to her posts about marriage and motherhood.

Truth be known: I personally think Williams doesn’t get enough credit for being the amazing tennis player and athlete that she is. David Foster Wallace famously wrote of “Federer as Religious Experience” and while the eulogized virtues and habits would certainly differ, someone needs to write the same kind of piece about Serena Williams. If they did, they might be wise to use Kathryn Lofton’s new book, Consuming Religion, as their guide.

Given her substantive gifts, it would certainly be tempting to simply condemn the hypermediated interests in Williams’ so-called “private life” as ephemeral, pop culture noise. But, Lofton’s field-defining study might suggest, condemning that noise would just play into the ideology of secular fundamentalism that is convinced of its separation from ‘religion’ and is intent on disavowing the violence it cannot but enact and affect. Most basically, however, pop culture can only be so dismissed if its power to organize and manage experience is not taken seriously enough. As Lofton reminds us, conjuring the ghost of Émile Durkheim, the study of religion is nothing if it is not the study of the ways in which “our socialization is our humanization.”

Departing from a central conviction that, “if we are to understand what religion is, we must understand who we are in relation to it, in relation to what we define as our social life in this time we call secular,” Lofton tightens the assumed gap between religion and pop culture by using treatments of, among other subjects, TV binge watching, office cubicles, Britney Spears, the Kardashians, the corporation as sect, contemporary parenting, and Goldman Sachs. In the age of selfie sticks, Lofton thus brings the study of religion up close and personal with its own ‘othered’ and refracted reflection in the mirror. Agreeing with Durkheim’s assessment that, “religion seems destined to transform itself rather than disappear,” Lofton proceeds to explore the dynamics of secular ritual and religion by way of carefully chosen case studies.

***

Lofton’s first chapter, “Binge Religion—Social Life in Extremity” takes direct analytical aim at a quintessentially 21st century Western bourgeois ritual so many of us now partake in: binge watching.

My partner and I recently binge watched the full seven seasons of Game of Thrones. Doing so became a ritual of sorts. Given the logistics of our schedules this year, we usually don’t get home until 7:30 P.M. At that point, I could have continued to respond to emails but, after the dog was fed and chicken coop door closed, I really looked for a way to separate myself mentally from work (especially since I have found that social networks that include work colleagues can make this a more difficult proposition than it might have been twenty years ago when I graduated from college). My partner had, for months been hearing coworkers rave about the show at work and asked me if I wanted to join him in watching the show. Even though I initially had some moral reservations (I had heard there was gratuitous violence and an unnecessarily gendered expression of violence at that), I thought it would be fun to do something together after our busy work days. The dog would sit on the couch beside us. Over the course of the next several months, we made our way through seven seasons of the show, spending an average of $30-40 to download each season from Amazon.

Since the immersive experience of binge watching is linked to technologies of social organization (scientific, economic, political, domestic), it conjures the ‘religious’ not simply in terms of metaphorical hyperbole but in an analytically precise Durkheimian sense. Generations of moderns (and religious studies readers), of course, have been trained to look for the religious in churches, synagogues, temples and mosques. Lofton shifts our attention to that which has already stealthily captivated it under the guise of consumer freedom and choice. She offers, “the last ten years of scholarship on secularism, however, has worked to show that secularism is not the least bit minimal in its engagements, classifications, bureaucracies, or habits.” It is today a common sight: Americans at the couch, spending time together by binge watching a show. Lofton asks: “Why should we not see ourselves, in these consumer contexts of binging and streaming, fingering and uploading, spending and screening, as sorts of fundamentalist seculars, choosing the dialectic of mechanized intimacy over and above one of interpersonal encounter and intimacy?” Sheesh, here I am constantly pleading with my students to put their phones away and talk to each before class starts—like we would do in the good ol’ days.

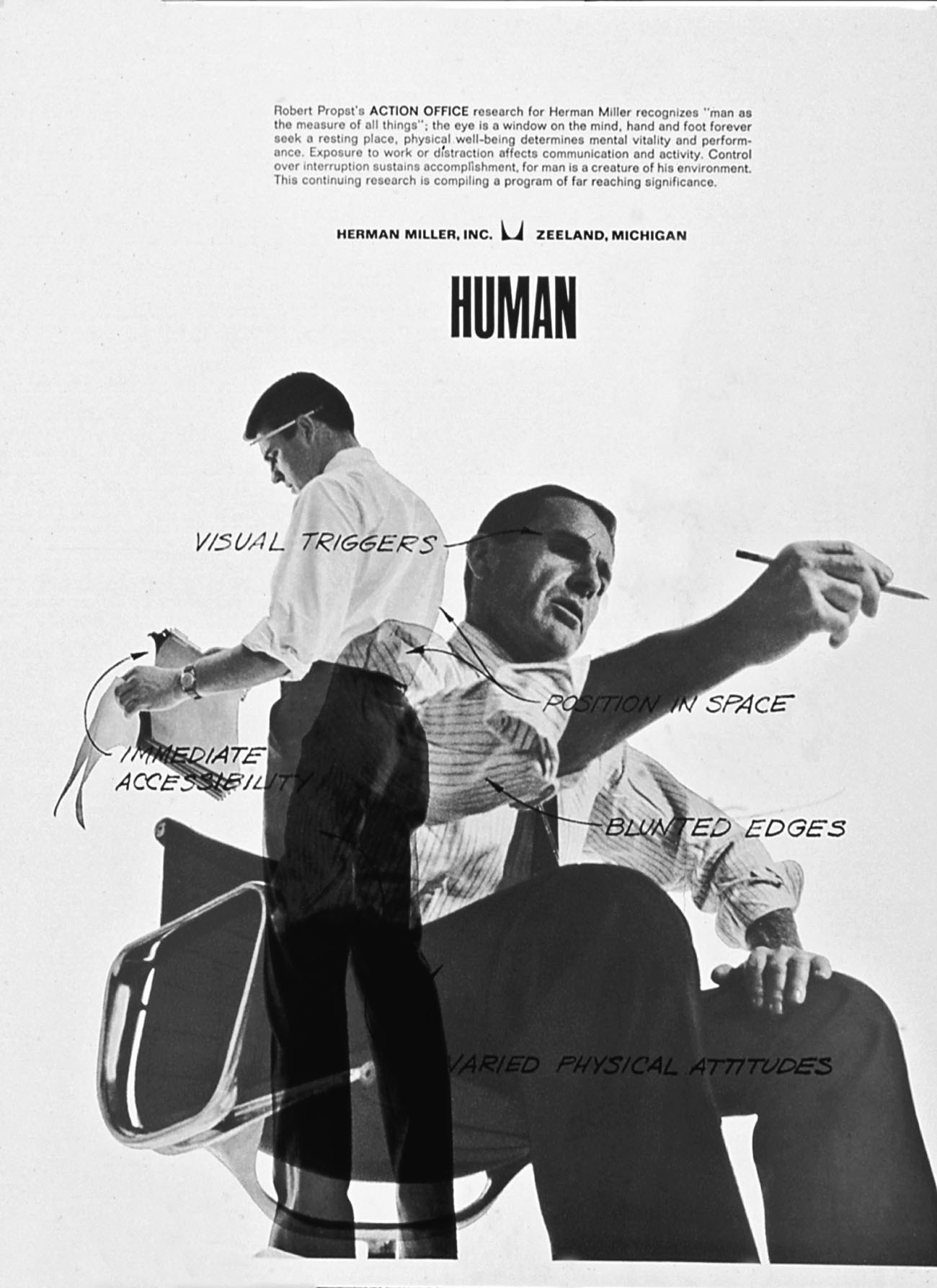

The religious history of the American office Lofton provides in Chapter 2 examines the ‘ontological consequences’ of a “particular product line offered by a specific company in the mid-twentieth century.” In this chapter, Lofton’s attention is on the “hermeneutic abundance” inhered in the history the Herman Miller Research Corporation, which in the mid twentieth-century played “a central role in the popularization of European modernism in America,” especially by way of its Action Office product—otherwise known as the office cubicle. It is perhaps simultaneously the clearest and most surprising example of religious determination Lofton surveys.

Here, Lofton documents the kinds of theological and religious valances Max Weber taught us to attend to. A product rooted in a particular corporate biography tethered to geographical and personal histories, Action Office, we learn, bears the traces of “Neo-Calvinist civility” and a “dissenting Baptist pugnacity.” However, Lofton’s treatment of Action Office is also appropriately mediated and dialectical. At its broadest ebbing, the argument is that secular Capitalism’s most “unspecial” (ubiquitous, neutral and simple) things can serve as secular religion’s most powerful “missionary tool(s)” and can be the most telling symbols of its metaphysical arrangements and commitments. In the case of Action Office, a modernist desire to support, “new connections, new visual landscapes, and new postures,” at work sadly gave way to, “the dream of a comfortable support system for the seated back.”[1] Alas, plenty of Americans still find themselves living that “dream”.

Today, the undoing of the metaphysics of the cubicle also makes the news. As Silicon Valley ritualizes its philosophy of working while you play and sells this dream of ludic labor to elite sectors of the new economy in the name of creativity, comfort, and connection, Lofton’s chapter serves as a historical reminder that what is old is also new again. Capitalism has always attempted to manage the spirit of work and there is little to suggest that the Google playroom jettisons this prime directive.

As Durkheim understood well, all socialization involves the sacrifice of autonomy for the sake of group consciousness.[2] This is an especially hard and fast rule at work. Among many related things, the Cambridge Analytica scandal re-problematizes and re-politicizes the issue of invisible labor. Google wants us to play at work. Facebook makes our leisure work for them. In the information society, our leisure is collected, packaged, sold, and analyzed as ‘data’ that is later redeployed to organize and manage us in turn. The technologies– and therefore the political implications—are certainly new. As we are reminded by Lofton’s cultural history, however, the attendant tensions between structure and agency are not.

***

Despite her phenomenal success, it is simply an ontological fact that Serena Williams has had to embody and navigate a very different reality than any of her male tennis pro counterparts has had to. On her journey to achieving iconicity, Williams, who famously learned to play on the public courts of Compton (the southern California city of Straight Outta Compton fame), has long had to endure racist and heterosexist ambivalence around her muscular physique and has found the still very white and wealthy American tennis scene sometimes openly hostile despite her prodigious talent.[3] At once loved and periodically cut down to size (a measurement specifically contoured to her black, female body), Serena Williams, a fashion forward super athlete who hangs out with celebrity friends like Beyoncé, is, in the terms set forth in Consuming Religion, sacrificed to our ritual consumption of her celebrity. She is sacrificed (where others might not be) because sacrifice is one of secular religion’s fundamental rituals.

An advertisement for Herman Miller’s Action Office

The most arresting and haunting chapter in Consuming Religion is given the title “Sacrificing Britney—Celebrity and Religion in America.” In it, Lofton shines light on the logic of violence which animates the contemporary consumption of celebrity. More than that, however, here she most directly conjures forth to the scene of analysis considerations of gender (and, by extension, difference) that, while I think strategically understated in the monograph, begin to clear paths that the study of religion desperately needs to follow.

Celebrities, Lofton argues, are transfigured into ideas. “Transforming flesh into commodity,” celebrity fetish might evoke the theological procedures whereby a first-century Palestinian Jew became the Christian Christ or bodily suffering has been figured as salvific martyrdom. Through the abstracting process of celebrification, a human being is redrawn as a, “composite sketch, with parts and pieces, and accessories easily redacted and packaged, remembered and satirized.” The alchemized celebrity becomes a kind of mindscape, zeitgeist, discourse, or brand. For its part, as a cultural practice, the worship of celebrity has some mean spirited, even sadistic, registers.

As perhaps as even most people who avoid E! and the supermarket rags still know, once reborn simply as Britney, Britney Jean Spears has endured endless speculation, scrutiny, and gossip with respect to relationship problems, drug problems, mental health challenges, and weight issues. Like Serena, Britney has been raised up and then torn back down according to a formula that just cycles and repeats. What does this mediatized schadenfreude regarding Britney Spears’ personal challenges teach us about the dynamics of secular religion?

Lofton functionally connects the ‘ritualized celebrity stripping’ to which Spears has been periodically subjected to a, “sacrifice made on behalf of a social body, a sacrifice that centralizes communication with, and thinking about, the legitimate social order (or relationship to divinities, to ideals, or higher principles).” Sacrificial logic, she reminds us, “prompts the entire community to select victims outside itself for the sake of itself, to kill someone who isn’t them to keep them going.” Lofton writes, “watching those declines and ascents might be read as a sort of public sacrifice, a Eucharist consumed by a public needful of something as an ironical counterpart of sacral nationhood and moral family making.” That is, Britney is sacrificed and consumed in order to keep the demons of fundamentalist religion at bay. While, as we learn, the religious right prays for her soul, the adherents of consuming religion take pleasure in doing her in so that we might periodically raise her back from the dead. How can we otherwise delight in the ways in which Britney is Stronger if she isn’t made to have to get back up again?

Still from Brtiney Spears’ music video for “Stronger”

In her chapter on the Kardashian family (K-Klan), Lofton asks, “Is the only way to become a woman with corporate power to commodify your capacity to expand your kinship networks, namely your ability to sell products that magnify your physical features?” Her suggestion throughout the monograph as a whole is: as a structural matter, financial and political power remains unevenly distributed across axes of sex, race, gender, and other fields of difference. And we ought not be fooled: women (and poor women and women of color especially so) are still disproportionately burdened with the tasks of material toil. The great Serena Williams rejoining her quest for tennis greatness only months after a delivery which almost cost her life is an almost scripted given. Despite the hollowing claims of corporate feminism, homonationalist discourse, and official multiculturalism, the center is not a rainbow. Difference is consumed to perpetuate the order; we lean into our own consumption.

***

In her discussion of binge watching, Lofton troubles the assumed borders of fundamentalist religion. The men who flew airplanes into the Twin Towers on 9/11, Lofton writes, “identified in those towers the wrong religion.” One of these men, Mohamed Atta, spent September 10, 2001 shopping at Walmart and eating at Pizza Hut. Lofton writes, “the confrontation between Atta and the North Tower is a confrontation of value in which porn, Victoria’s Secret advertisement, and Showtime programming constitute subjects of intense consumer practice equal to the maximal absorption (we assign) to the terrorist. These are two extremities facing off with each other.” Lofton adds, “binaries are not static opposition as much as they are descriptive of a tense purlieu of their differentiation.” Violence is endemic to the logic of secular fundamentalism. Secular fundamentalism demands its own bogymen and sacrificial victims. Lofton’s intellectually dizzying and absolutely brilliant book calls our attention to the fundamentals of our consuming religion. Our commercial temples, celebrated virgin sacrifices, and sacred television dramas are not separate from ‘religion’ but important religious artifacts of, these, our supposedly secular times. As a counterpoint to New Atheism’s bright lines and an escalating Islamophobia, the suggestion is as pressing as it has ever been.

***

[1] Lofton explains that in order to accentuate the hoped for connections of the original design, workers had to “come to terms with modularity” and actively participate in shifting their modules, which they often did not. High real estate costs also led companies to cram cubicles together, a state of affairs that we are today more likely to associate with the office cubicle.

[2] The American anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski, in turn, argued that Durkheim’s account of socialization leaves little room to account for the existential textures and dimensions of social and collective ordering. Although it is without the scope here, I find that Lofton avoids suffocating the livingness of the phenomena that interest her by interjecting her own voice and intersubjective experiences.

[3] For fourteen years, Williams boycotted a major tournament at Indian Wells (California) due to a well-publicized incident involving racially motivated taunting. She announced her return to the event in 2015 with a videogram in which she urged her followers to support the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit that provides legal representation to poor persons of color denied equal treatment by the legal system.

***

George González is currently Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Monmouth University. Beginning August 2018, he will be the Assistant Professor of Sociology and Anthropology (Study of Religion) at Baruch College, CUNY. His research interests lay in the sociocultural legislation of Western metaphysics and the concrete and specific form of power that has attached to liberalism, as a historically specific kind of cosmology. He remains especially interested in approaching the study and criticism of postsecular, neoliberalism through the framework of religious social change. He is the author of Shape-Shifting Capital—Spiritual Management, Critical Theory, and the Ethnographic Project and is currently working on a multi-site ethnography and historiography of the ritualization of consumer capitalism and began fieldwork with the famed radical performance troupe, Rev. Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping in early 2017.