Christian Nationalists and Climate Skepticism

How outrage media stokes Christian nationalists’ climate change denial

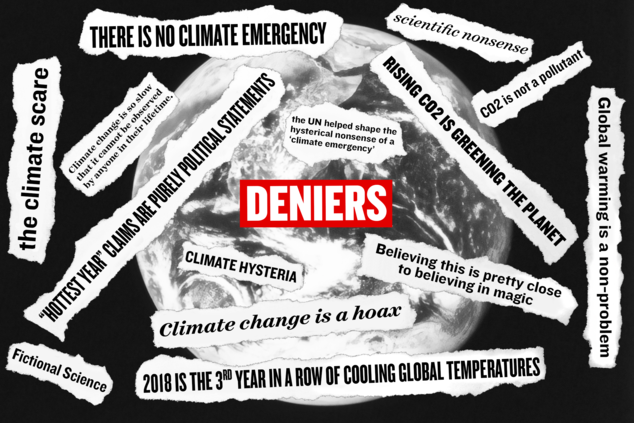

(Image courtesy of the National Resource Defense Council.)

I fumbled with my phone, one hand on the steering wheel, trying to get a video titled “Faith, Family and Freedom” to play. The video was a recording of a Christian nationalist event, and in an hour, I was set to interview the speaker, John (a pseudonym). I had reached out to John because he was the leader of a group with roots in the Tea Party, which interested me for reasons I’ll soon explain. But his house was 60 miles away, and so I planned to use the drive to listen to videos on his website. Finally, the video loaded, and I pulled out onto the road, volume turned up.

“We live in perilous times,” John began as the video started. “Today good is called evil, and evil is called good. Our faith, families and God-given freedoms are under relentless attack. We can and must do something, or everything we hold dear will be lost forever.” He painted a dark vision of America, in which liberals were destroying its foundations and the country itself. The once great nation was now “damned, not praised.” Critical race theory was destroying schools, followers of “Judeo-Christian” traditions were being “demonized,” and Marxists were serving up history in bowdlerized forms. My pulse quickened as I listened. Was it safe to be alone with this man? As an academic, I get to choose my research topics. Did I really need to do this?

My reasons for planning the interview began with a book I wrote about the phenomenon of climate skepticism—not accepting that climate change is real, serious, or caused primarily by human activities—within America’s white evangelical community. Many observers of evangelicalism have suggested that their high levels of climate skepticism are simply a side effect of conservative politics. But a survey from 2013 found that 31 percent of evangelicals mentioned religion to explain why they did not believe the climate was changing. I soon discovered that evangelicals were not the only group to justify their climate skepticism with religion. Between 2011 and 2013, 17 percent of skeptics who gave religious reasons were Catholic. Curiously, Catholics explained their skepticism in ways that mirrored evangelicals. One white Catholic from Florida explained that she didn’t believe the climate was changing because “Only God controls the weather.” Similarly, a white evangelical Protestant from Michigan insisted, “God controls everything.”

My reasons for planning the interview began with a book I wrote about the phenomenon of climate skepticism—not accepting that climate change is real, serious, or caused primarily by human activities—within America’s white evangelical community. Many observers of evangelicalism have suggested that their high levels of climate skepticism are simply a side effect of conservative politics. But a survey from 2013 found that 31 percent of evangelicals mentioned religion to explain why they did not believe the climate was changing. I soon discovered that evangelicals were not the only group to justify their climate skepticism with religion. Between 2011 and 2013, 17 percent of skeptics who gave religious reasons were Catholic. Curiously, Catholics explained their skepticism in ways that mirrored evangelicals. One white Catholic from Florida explained that she didn’t believe the climate was changing because “Only God controls the weather.” Similarly, a white evangelical Protestant from Michigan insisted, “God controls everything.”

The curiously matching responses of white Catholics and white evangelical Protestants became a footnote in my book, but I kept wondering about their connections given that these traditions have such different histories. Several years later, when sociologists Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead published a book about an ideology they called Christian nationalism, I began to wonder if I had finally found the answer.

A core belief of Christian nationalists, who comprise about 20 percent of the American populace, is that America was founded as a Christian nation. This view has long been popular among white evangelicals. But what Perry and Whitehead showed was that people in other religious traditions also shared this view. Indeed, almost 19 percent of Christian nationalists were Catholic. For Perry and Whitehead, Christian nationalism helped explain why so many Americans (not only evangelicals) supported President Trump. But intriguingly to me, Christian nationalism was also associated with climate skepticism, suggesting an underlying explanation for the matching survey responses I had observed years earlier.

I wanted to better understand the nature of this connection, but there was a problem. Christian nationalism is a term used to describe survey results; few people self-identify as a Christian nationalist. How could I identify them, other than by going back to the same evangelical churches I had already visited? (About 55 percent of Christian nationalists are evangelical Protestants). Eventually I settled on the Tea Party, which has been linked to both anti-environmentalism and to Christian nationalism. Intriguingly, a 2016 survey by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that 38% of Tea Party members agreed with the statement that, “God controls the climate, therefore people can’t be causing global warming.” Surprisingly, this was 8 percentage points higher than the percentage of evangelicals and born-again Christians who also agreed with that statement. Hence the Tea Party movement and its successors seemed like a useful place to begin my inquiry about the connection between Christian nationalism and climate skepticism.

***

John, a white, retired educator in his seventies, has strong opinions about climate change, but less important than these views are the underlying connections to his two primary concerns: “free and fair elections” and “no vaccine mandates.” Notably, in all three cases, John held views that had been debunked by experts. John thought the 2020 election was riddled with voter fraud (it wasn’t); he thought the COVID-19 vaccine was more dangerous than COVID-19 (it’s not); and, regarding climate change, he argued that “the climate is changing, always has been changing. But man doesn’t affect it much.” (It has been clear for decades that human activities are the primary cause of climate change.) How did he end up on the opposite side of experts in all three cases? What was the common thread?

Before I consider the answer, I should clarify why it matters. John is only one person, to be sure, and the Tea Party may only have had, at its strongest, 200,000 active members. But if scientists have known for decades that human activities are causing climate change, why hasn’t the U.S. (as of this writing) passed national-level climate legislation? Why did the U.S. exit the Paris Climate Agreement in 2020? (We rejoined in 2021). The delays in action on climate change are not rooted in science. And the Tea Party’s remaking of the Republican Party, with its activism against taxes and disparaging view of the role of government, has had tremendous implications for the climate movement in the U.S. More broadly, Christian nationalism seems increasingly to be uniting disparate segments of the political right, in ways that have unclear, but inauspicious, implications for our nation’s ability to deal with climate change.

(Tea Party Protest. Photo credit: JEWEL SAMAD for Getty Images.)

Based on my earlier observations among evangelicals and my new work among Tea Partiers, I am convinced that one angle we should examine closely to explain the connection between Christian nationalism and climate change skepticism is media, especially conservative media. Through television, radio, magazines, websites, and podcasts, conservative media has grown tremendously since its origins in the mid-twentieth century. Without media to convey misinformation (misinformation refers to false information that is unintentionally spread, while disinformation is intentionally spread), only small segments of the population would be able to hear these ideas, much less take them as fact.

As historian Nicole Hemmer explains in her book Messengers of the Right, the individuals who first laid the groundwork for today’s conservative media, beginning in the 1950s, did so not simply for commercial reasons, but as part of an ambitious, culture-shaping agenda. Up through the 1970s conservatives believed that liberals “controlled the institutions that disseminated ideas and shaped public opinion: the schools, the media, the publishing industry. And the people who controlled those institutions controlled the culture. . . If conservatives wanted a better America, they would have to invest in better media.”

In the early days, conservative media often represented the interests of its funders by disparaging union leaders whose activism threatened to reduce owners’ profits. But in order to succeed in remaking American culture, conservative activists needed to get large numbers of Americans whose interests were not served by conservative media to consume it. A strategy they eventually came up with—which is still in use today—was to charge the media establishment with liberal bias. This tactic had the benefit of playing to the public’s instinctual desire to hear “both sides of the issue,” while also flattering the common man’s belief that he was smart enough to judge for himself which argument was most convincing.

It was not until the elimination of the Fairness Doctrine, and two of its corollary rules that prohibited personal attacks and political editorials, that the “outrage media” we know today began to flourish (the Fairness Doctrine was repealed in 1987, while the corollary rules were eliminated in 2000). In the post-Fairness Doctrine world, broadcasters no longer had to devote programming time to both sides of an issue, and on-air personalities could make outlandish personal attacks without facing legal repercussions. Both changes incentivized broadcasters to produce outrageous, inflammatory content, which attracted listeners and advertising dollars. Hence, what the political scientist Jeffrey Berry and sociologist Sarah Sobieraj call “the outrage industry”—media that is consistently offensive, hyperbolic and controversial—was born.

These changes transformed the media landscape. But the alterations were not politically neutral. Rather, the new format was vastly more favorable to conservative media, which soon outstripped its mainstream counterpart. One study from 2007 found that 91 percent of total weekday talk radio programing in the U.S. was conservative.

Media deregulation also enabled misinformation to proliferate. A 2011 Pew Research Center study reported that nearly half of regular Fox News viewers wrongly believed that Affordable Care Act legislation would include “death panels.” More recently, a study published in the Canadian Journal of Political Science found that right-leaning media viewers were “more than twice as likely to endorse COVID-related misinformation.”

Climate change, I believe, belongs in this history as well. One study on conservative media’s impact on climate change attitudes found that Fox News chose to interview a greater proportion of climate change deniers than CNN and MSNBC, giving Fox viewers the false impression that denialist views were mainstream. Not coincidentally, even after controlling for other possible influences, Fox News viewers were less likely to accept the scientific consensus on global warming. Another study found that when conservative political commentator Rush Limbaugh spent more time disparaging climate change on his show, Republican concern about climate change declined. Limbaugh was actually named “Climate Misinformer of the Year” in 2011 by Media Matters for his dismissive, misinformation-ridden coverage.

(Fox News coverage of climate change denial)

Sure, conservative media may spread misinformation, but what of critical thinking, one might ask? What keeps people like John convinced of alternative facts, especially when there is so much counterevidence available? Curious, I asked John about how he decided which sources to trust. “I don’t like to turn on the radio or the TV to be propagandized,” he told me. “Give me facts, give me something interesting, but . . . don’t pretend I’m stupid.” He named Whistleblower magazine as a valued source. (Whistleblower is published by the far-right publisher WorldNetDaily and ran a July-August cover story that boasted, “Yes, the 2020 election was stolen”). He also positively assessed Epoch Times, a far-right religiously-affiliated newspaper, saying it was “like a very good version of the Wall Street Journal . . . They have good reporters. They have to verify their sources.”

A few days after interviewing John, I met an associate of his who led a different Tea Party group, whom I’ll call Patrick. Still curious about media consumption, I posed some of the same questions. Patrick had different preferences, but a similar attitude toward mainstream sources. He named Newsmax (whose CEO, Chris Reddy, is a fervent Trump supporter) as trustworthy, while he disparaged CNN as “Constantly Negative News,” NPR as “National Propaganda Radio” and MSNBC as “off the wall.” He noted matter-of-factly that there was “a night and day difference” between what he was hearing from the sources he trusted and what was appearing in mainstream news. But what I found fascinating was that he interpreted this as evidence that consumers of mainstream news were the ones being misled. Like John, he was worried about consuming mis- or disinformation. But he had latched onto both in the process of trying to avoid them.

While perhaps surprising, John and Patrick’s sentiments were exactly what we should expect from consumers of outrage media. As Berry and Sobieraj note in The Outrage Industry, debunking mainstream media stories is a core strategy in conservative media, given the many opportunities it offers for crafting dramatic, emotionally-engaging storylines. In fact, outrage media addresses most social and political subjects “not as serious issues in need of examination but as golden opportunities to gain footing in the ongoing contest to re-inscribe the sense of political superiority and aggrieved solidarity that proves effective in validating audience preferences and winning the ratings game.” Bad for society, but good for the bottom line.

If media and misinformation were relevant to the climate attitudes of my Tea Party interviewees, one might wonder where, if at all, religion enters the picture. Both men were serious about their faith (John was Catholic and Patrick was a non-denominational Protestant). But there were not any teachings specific to their faiths that seemed to influence their attitudes toward climate change. Rather, it was the kinds of outlandish persecution narratives that thrive in outrage media, especially the idea that environmental policymaking might become a pretext for religious persecution. For example, John had argued in his “Faith, Family and Freedom” video that, “Our children are being terrified, traumatized and propagandized [by climate activists] to do the Left’s bidding.” Similarly, in explaining how people of different religious backgrounds felt comfortable attending his Tea Party meetings, he underlined that they all faced a common threat: “It’s not going to matter if you’re a Baptist, evangelical or Catholic . . . when they decide to do away with religion in America, they’re going to put us all in the same gulag.” Patrick told me he believed that the U.S. was entering an era of religious persecution that mirrored what had happened in Germany in the 1920s through the 1940s (incredibly, though somewhat predictably, he was thinking of the persecution of Christians, rather than Jews, during this period). Some of this persecution had environmental ties, he added, mentioning a controversy in Maryland where, he said, churches had been forced to preach “green sermons” to avoid paying a “rain tax” (“rain tax” is a term critics coined to refer to an unpopular storm water run-off fee implemented in Maryland in 2013, which applied to private properties, including churches).

Overall, John and Patrick’s comments suggested that climate change and environmental issues served primarily as additional grist for their mill of grievances. Ultimately, that means we are unlikely to see substantive discussions of climate change, or see climate policy initiatives replace inflammatory and misleading diatribes, anytime soon—unless something changes.

But what, then, should we do about this situation? In the short term, we may be able to convince more people in our communities that climate change is a real and serious problem by focusing less on the science and more on shared values, as climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe argues. But in the long term, this kind of one-on-one approach is futile. We cannot address the climate crisis—not to mention vaccine hesitancy and claims of election fraud—until we can have a substantive debate about them. And we can’t have a substantive debate about them until our citizens have accurate information.

At the root of this problem, then, are the incentives of commercial media, which are misaligned with the public’s need for high quality information. As media scholar Victor Pickard argues, the best way to fix our “misinformation society” is to dispense with the notion that the marketplace will deliver us the news we need. Good information is not a commodity; it is a public service—and an essential one in a democracy. To get back on track, we urgently need a well-funded public media system.

***

Other than the misinformation he preached, John seemed like a kind man who had devoted his career to special education, and choked up when he talked about hoping for a better life for his grandkids. Sitting with him at his cluttered table, with board games stashed in a corner by the window, and the Virgin Mary looking down on us, my pulse slowed. The problem is not bad people, but inaccurate information. The solution is neither to demonize nor to proselytize its victims. The solution is to fix the system.

Robin Veldman is an assistant professor of Religious Studies at Texas A&M University and the author of The Gospel of Climate Skepticism: Why Evangelical Christians Oppose Action on Climate Change. As part of her broader interest in how religions shape perceptions of the natural world, she is working on a book on the environmental politics of Christian nationalism.