Charcoal in an Empty Room: On Mary Beard’s How We Look Now

Iconoclasm can be a method of radical critique

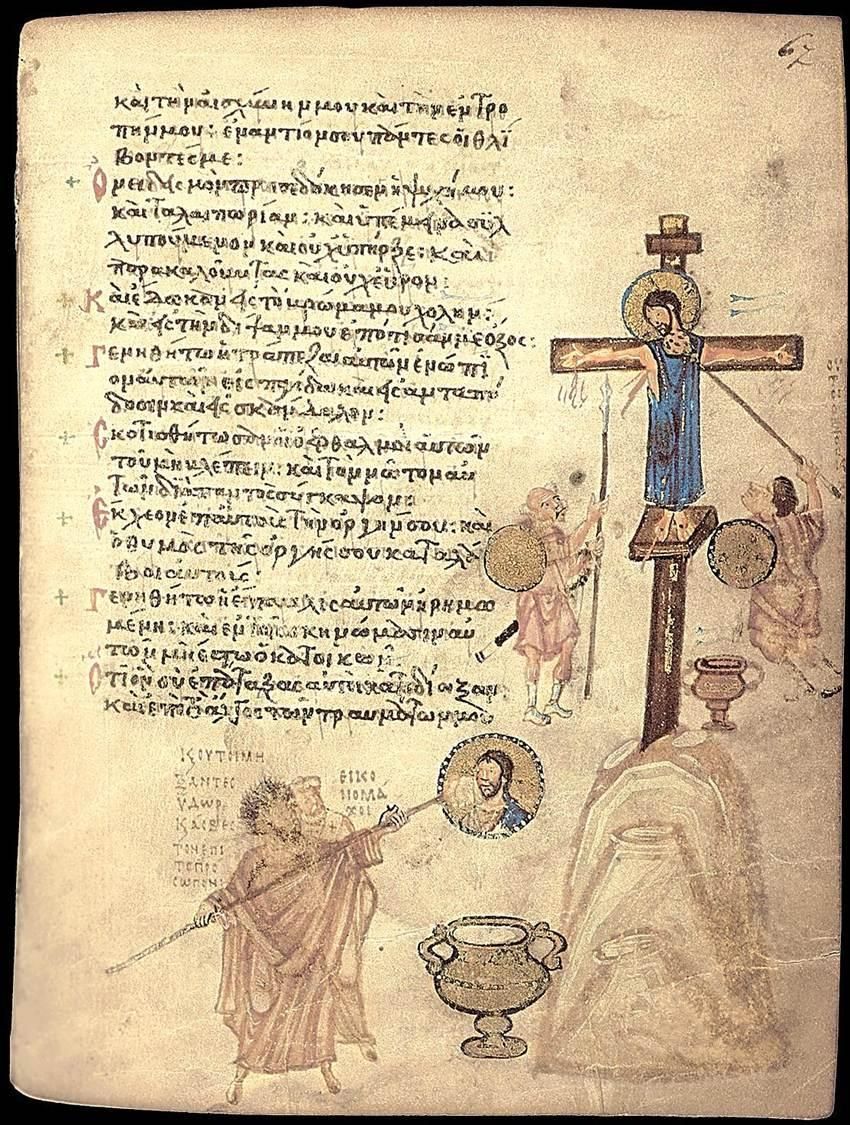

In the ninth-century Byzantine Chludov Psalter, there is an unusual picture of Constantinople’s patriarch, John the Grammarian. Despite his mild-mannered name, The Grammaticus (as the Armenian theologian was titled), is depicted defacing an icon of Jesus Christ — with a long sponge-tipped brush, he wipes away the surprised face of the Son of Man. In order to make their intent explicit, the illustrators of the Chludov Psalter included an inscription from Psalm 69:21: “in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink,” a passage Christians associate with the moment when a Roman centurion hoisted a sponge to the dying Christ.

At the time, possibly inspired by the austerity of their Abbasid rivals to the south, Byzantine emperors and bishops were attacking the validity of images in a fury that wouldn’t be replicated in Christendom until the height of the Protestant Reformation. The Chludov Psalter was one of only three illustrated psalters to survive the iconoclastic period.

Juxtaposing John the Grammarian with Christ’s executioner makes a clear visual argument: iconoclasm is deicide. As classicist Mary Beard observes in her new book, How Do We Look: The Body, the Divine, and the Question of Civilization, “lurid stories were spread about the evil of the iconoclasts, which went so far as to suggest that the wickedness of those who destroyed images of Jesus were second only to those who crucified Jesus in the first place.” One of those wicked iconoclasts was the Grammarian, who in the Chludov Psalter wears a blood-red chiton with his brown hair disheveled. Having found himself the victim of poetic justice, entropy has ironically smudged the bishop’s features over the centuries.

The Chludov Psalter doesn’t appear in How Do We Look, but in many ways it’s a helpful encapsulation of Beard’s revisionist arguments. A gorgeously illustrated, slim volume, How Do We Look marshals Beard’s prodigious learning to derive an implied theory of art; the book being an opportunity for the celebrated classicist to present readings of art, canonical and obscure, ancient and modern, sacred and profane. Beard rejects the tired Great Man Theory, preferring rather to put “viewers of art back into the frame,” emphasizing with crucial ambiguity that the “history of art is about how we look.”

Rather than a predictable litany of (usually male) geniuses, Beard’s approach acknowledges that art is produced in its consumption, that our ways of approaching images are instrumental in interpreting them. Beard’s argument centers on “two of the most intriguing and contested themes… the art of the body… [and] images of Gods and gods.” To that end, Beard is also concerned with presence and absence, seeing in the theological debates between iconodules and iconoclasts an aesthetic dialectic that defines art history. In the Chludov Psalter we see the paradoxical tensions of this dynamic, an image of image destruction made in resistance to those very image destroyers, a claim that “even in the most radical cases of iconoclasm, art lives on – inextricably bound to faith.”

Beard’s book is a companion to the BBC/PBS co-produced documentary update of Kenneth Clarke’s classic 1969 documentary television series Civilization. More popular in Britain than it was in the United States, Clarke’s documentary introduced a generation of viewers to art, performing for the humanities a purpose not dissimilar to what Carl Sagan’s Cosmos did for science. This 2015 sequel, with the more ecumenical title of Civilizations, features Beard, Simon Schama, and David Olusoga attempting to extend the series beyond the patriarchal and patrician perspective of Clarke’s conservative original. They expand their gaze across cultures and feature a diversity of artists, including women, who’d been entirely ignored in the 1969 show. Viewers aren’t limited to the Apollo Belvedere, but we also consider Olmec heads; our conversation doesn’t end at the crucifixions of Tintoretto, but also includes the Hebrew calligraphy of the medieval Spanish Kennicott Bible. A certain type of viewer, with a condescension that often masquerades as rusticity, will label such expansive attempts as “politically correct.” To such anti-humanists, whether they dwell on the Intellectual Dark Web or in a dive bar’s dark booth, one can only respond with Terence’s injunction from the second-century that “I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me.” Civilizations takes part in that venerable, humanistic “art in the dark” method of pedagogy, where thoughtful strolls through the Louvre or Uffizi, contemplating a Michelangelo or Caravaggio, display education and curiosity. In their varying ways, this is the tradition of the tony historian Michael Wood, the delightfully eccentric Sister Wendy Becket, and especially Clarke. But more than any of those personalities, the new Civilizations is indebted to John Berger, and his 1972 series and companion of the same name Ways of Seeing, where he claimed that “Every image embodies a way of seeing.”

Beard is an ideal commentator; a public scholar who remains a scholar, embodying that sadly rare combination of erudition and the phrase finely wrought. For a Cambridge don whose dissertation was on the unsexy topic of Cicero, Beard is the only classicist to ascend to Steven Pinker levels of fame, but she’s deserving of her popularity. Classics are a particularly unlikely field to lend itself to popularization. Yet Beard, along with her upcoming acolyte Sarah Bond, is adept at letting her knowledge of the Greeks and Romans inform contemporary political questions without making the common error of figuring the ancients as “simply like us, but in togas.” Beard’s popularity is in large part due to her SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, which is the best, recent volume on the subject for a general audience, as well as for her incredibly popular blog “A Don’s Life” at The Times Literary Supplement. If you’re anything like me, then SPQR will help you finally keep the Julio-Claudian dynasty separate from the Flavian.

Beard is an ideal commentator; a public scholar who remains a scholar, embodying that sadly rare combination of erudition and the phrase finely wrought. For a Cambridge don whose dissertation was on the unsexy topic of Cicero, Beard is the only classicist to ascend to Steven Pinker levels of fame, but she’s deserving of her popularity. Classics are a particularly unlikely field to lend itself to popularization. Yet Beard, along with her upcoming acolyte Sarah Bond, is adept at letting her knowledge of the Greeks and Romans inform contemporary political questions without making the common error of figuring the ancients as “simply like us, but in togas.” Beard’s popularity is in large part due to her SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, which is the best, recent volume on the subject for a general audience, as well as for her incredibly popular blog “A Don’s Life” at The Times Literary Supplement. If you’re anything like me, then SPQR will help you finally keep the Julio-Claudian dynasty separate from the Flavian.

Beard’s role as a blogger has endeared her to a public fascinated by complex scholarly debates but not content to see them dumbed down. She has been a model of how to stand against online abuse, as well as an advocate for the bullied, particularly when directed against women in academe. Such themes were explored in Beard’s 2017 Women & Power: A Manifesto, and are congruent with the new Civilizations’ canon expansion. But Beard’s argument takes on a more abstract gloss as well, one which owes much to Berger’s aesthetics (though the critic isn’t mentioned in How Do We Look), but departs from his Marxism in favor of an archetypal methodology, one which dwells in immanence and transcendence, embodiment and faith, as a means of critique. As with Berger, Beard focuses “on the people who looked at this art as much as on the artists who made it.” The result is both unconventional and ingenious, and though at times Beard’s treatment isn’t as detailed as it could have been, her analysis is still illuminating.

Some of that focus on looking is literal, since in her short volume Beard gives virtually no detail on artists themselves – that material being abundantly available elsewhere – rather providing brief sketches of exemplary viewers. For example, Beard considers the first-century Roman poet Julia Balbilla, who accompanied Hadrian’s imperial retinue to Thebes. There, Balbilla inscribed verse upon the monumental statue of Amenhotep III, the Romans having misidentified it as the mythic king Memnon. Famed at the time for a structural irregularity which caused a mournful whistle to be emitted every dawn by the statue, Beard examines how Balbilla interacted with the work itself. Still visible upon the base of that statue, Balbilla wrote that “Memnon the Egyptian I learnt, when warmed by the rays of the sun, /speaks from Theban stone. /When he saw Hadrian, the king of all, before rays of the sun, /he greeted him – as far as he was able.” Whatever the statue of Amenhotep “actually” was, it’s in viewing that a meaning for the work emerges. Beard argues that Balbilla’s epigrammata, a type of “extraordinary high-end graffiti,” is a record of interaction with the colossi. The classicist provides similarly adroit accounts of other viewers, such as the Victorian patron Christiana Herringham examining the Buddhist cave murals of Ajanta, and the 18th century German historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann whose influence Beard describes as a “distorting and divisive lens that is hard to escape.”

By refocusing from the viewed onto the viewer, Beard’s readings of those figures render certain conclusions that might be obscured in a more traditional account. Beard hypothesizes that “plenty of ancient Egyptian viewers, or ancient Romans, may have been just as cynical about the colossal statues of their rulers as we now are about the parade of images of modern autocrats.” We assume that monumental architecture implied monumental regard, but Beard convincingly claims that such statuary could equally signal profound insecurity, where the anxious authoritarian becomes “one target audience of these colossal images,” a telling argument when the commercial equivalent of televised state propaganda bases its programing on the president’s reactions. Beard’s point that the “person who needs to be convinced that he or she is preeminent, above the common herd, is none other than the ordinary human being who is masquerading as omnipotent ruler” is well-taken.

Iconoclasm is a method of radical critique; one which Beard says “may indeed reflect an artfulness of its own… [for] images of power are only as powerful as those who view them allow them to be.” Arguments on behalf of iconoclasm, from Plato’s The Republic to the Second Commandment, don’t deny the aura of images. Beard explains how in the third-century BCE rebels destroyed some of the terracotta soldiers of the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang, indicating not simple vandalism, but the “clearest sense of the power of those images.” Examine a chipped mosaic from ninth-century Byzantium, or a decapitated statue from sixteenth-century England, and you’ll notice that for iconoclasts it was often “only heads and hands” marked for removal, “leaving the body in place.” When John the Grammarian makes his argument that an icon is not Christ, it’s not the ass that he’s aiming for. In rupturing the most human aspects of representational art, the iconoclasts are admitting to the enchanted power of the image, for if such enchantment weren’t present there would be no pressing need to disrupt it, because “images often did something.”

It’s easy to figure the iconoclasts as the bad guys (and often fair enough). If you’ve spent Sundays at the Met or the Frick it’s hard to harbor much sympathy for the disheveled Grammaticus, or Oliver Cromwell stabling his horses under the white-washed walls of Ely Cathedral after the stain-glass windows have been struck, much less the Taliban levelling the Buddhas of Bamiyan with dynamite, or ISIS taking sledgehammers to the treasures of Palmyra. But at the risk of overextending my reading of How Do We Look, Beard does seem to be saying something about how a dialectic between iconodules and iconoclasts, between presence and absence, propels the history of images and doesn’t always literally entail stripping altars and smashing reliquaries. Both iconoclasm and iconodulism are intrinsically related, a continual debate over the distinctions between likeness and presence, sometimes a type of deconstruction more than barbarity. As Beard explains, “Civilization is a process of exclusions as well as inclusion.”

Boxer at Rest, c. 330 to 50 BCE

As an example of how iconoclasm can also work as a mode of aesthetic critique (and creation) and not just the taking of a sponge to an icon, consider Beard’s interpretation of Boxer at Rest, a celebrated bronze found in the ruins of Constantine’s Bath, a Greek or Roman sculpture from between the third and first centuries before the Common Era. As with The Dying Gaul from roughly the same period, Boxer at Rest challenges the “cult of youthful athletic prowess” which dominated Hellenistic standards of beauty. Beard writes that there was an “intense investment in the youthful, athletic human body, almost as if that was a physical guarantee of moral and political virtue,” and yet the bruised, battered, and torn body of the flabby middle-aged boxer is an iconoclastic assault on that cult. This is a civilization critiquing itself, the aesthetic dialectic in play. Beard writes that the anonymous caster “focused on a wreck of a human being,” where artistic aptitude has been put into the service not of golden ratios and carved pectorals, but a “broken nose and cauliflower ears,” where the fighter is “still bleeding from fresh wounds.” In a radical victory of brutal realism, whoever created Boxer at Rest was able to depict the fighter’s blood in copper and bruises in bronze alloy, so that what entropy and violence can do to a human body was clear. Boxer at Rest isn’t a depiction of iconoclasm; it’s iconoclasm itself caste in bronze.

Images such as that of the boxer take up full and even double pages in How We Look Now. This is a beautiful book, not unlike an exhibition catalog or artist retrospective that you might see for sale in a museum gift shop. Only a cynic would argue against just a little bit more beauty in our broken and fallen world. But the gorgeousness of the volume can also lend itself to an occasional superficiality. Perhaps a result of How We Look Now being tied to a television show, but sometimes the language can be uncharacteristically cliched for Beard, and exciting concepts are often not fully fleshed out. There’s a disappointment in that, especially since Beard is such an evocative guide. The ideas in How We Look Now – from the desire to move the gaze back to the gazer and placing questions of representation and religion at the center of art history – are novel enough that the brevity of the volume feels like a missed opportunity.

Then again, a collection of beautiful things doesn’t always have to be organized in a comprehensive way. If Beard is anything as a writer, she’s a master of the arresting historical detail, from Balbilla composing on the foot of Amenhotep to Muhammad’s argument with Fahima over a set of tapestries. If How We Look Now is the sort of book sold near the museum cash-register, then reading her book feels like strolling through a great museum. What Beard’s approach lacks in systemization, it makes up for by encouraging the reader to draw their own hypotheses and conclusions. That way Beard’s account does precisely what she says it will do: it puts the focus on the viewer rather than the artist, the reader rather than the writer.

One of such arresting details concerns the legendary first portraitist, Kora of Sicyon, the daughter of the sculptor Butades. According to Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, Kora was in “love with a young man; and she, when he was going abroad, drew in outline on the wall the shadow of his face thrown by a lamp.” Following the lead of his daughter, Butades sculpted a relief of this dark outline, the first portrait inspiring the first sculpture. Beard presents the anecdote as another fascinating fragment, but I think in the account of Kora’s invention of art there is a synthesis of all of How Do We Look Now’s crucial themes. The dark outline of a silhouette marked by charcoal on a wall is both a presence and an absence; the former because it’s literally a representation that had not been there before, the later because nothing is more of a lacuna than the darkness of a shadow. Kora’s sketching of this anonymous lover’s silhouette is the rare ancient account where it’s the man’s name that is unknown, and in his shadow caste by a living human there is evidence of the body, but there is something sacred, holy, and divine about the lack of detail. Kora’s is an iconoclasm of feature, as Beard writes, this is “a story of loss: not in this case of death but of poignant absence of another kind.”

Dibutade ou l’Origine de la peinture, Jean-Baptiste Regnault, 1786

Art is the process of enchanting and disenchanting, of stripping altars and gilding them once more. Aesthetics must always be spoken of in the language of via negativa; its true subject is what Paul in Acts 17:23 called the “Agnostos Theos,” the “Unknown God,” which the Athenians still prayed to, and whom the apostle associated with the one, true God. Such is the nature of divinity, always impossible to depict with any absolute accuracy, that the Athenians in an act of uncharacteristic iconoclasm anticipated the Second Commandment and depicted the Agnostos Theos as an absence, as a nothing. A little less than a century before Paul delivered his sermon at the Areopagus, and the Roman general Pompey completed his siege of the Jewish capital of Jerusalem, and with hubris he stormed into the Temple’s Holy of Holies. There Pompey hoped to find gold and jewels upon the statue of the Jewish God. He found no treasures; rather, Pompey came upon the greatest, holiest, most beautiful representation of divinity ever made, all shadow and darkness like Kora’s charcoal on her father’s wall. Pompey found an empty room.

***

Ed Simon is a staff writer at The Millions and the Editor-at-Large of The Marginalia Review of Books, a channel of The Los Angeles Review of Books. He holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University, and is a frequent contributor at several different sites. His collection America and Other Fictions: On Radical Faith and Post-Religion was published by Zero Books in 2018. He can be followed at his website, on Facebook, or on Twitter @WithEdSimon.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.