Ceding Authority: Notes on Identity and Power in the Classroom

How can we support students whose identities and experiences are different from our own?

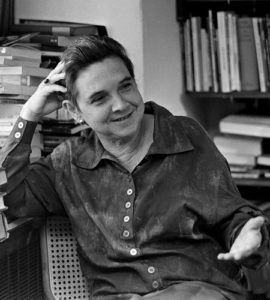

This field note from Abby Kluchin began as a lecture delivered at Ursinus College’s first Pride festival in April 2019. After she delivered the lecture, Kluchin posted the text on Facebook. I asked Kluchin to expand on her original thoughts and submit them as a “field note” for the Revealer. Our Field Notes section is “an ongoing forum where scholars and journalists can share new work as they do it.” In the piece, Kluchin reflects on the work of teaching as she does it. Originally trained in philosophy of religion, for the last seven years Kluchin has taught Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies (GWSS) and Philosophy courses at Ursinus. She also coordinates the college’s GWSS program and co-directs the Teaching and Learning Center. As you can imagine, faculty often go to her for advice, especially around inclusion and equity in the classroom, particularly when they have questions about teaching their LGBTQ+ students. She wrote this lecture in an attempt to codify some of the lessons she has learned. We are publishing it in the Revealer because of the ways Kluchin helps us think through the challenges of adapting pedagogical practices and ways of speaking and writing that seem effective, but that our students and readers may ask us to change. We hope her thoughts will help all of our readers — in classrooms and outside of them, in Religious Studies and other places — to ask similar questions about their own approaches to teaching, learning, and interacting with others.

– Kali Handelman, Contributing Editor

***

Mural of queer artist and healer Kiam Marcelo Junio

Every classroom is a risky space of complicated asymmetries of power and knowledge. I am familiar with the texts I assign and their contexts in ways that my students are not, at least not yet – and that is a position of power. But there is also a profound authority that students wield in asserting their own identities and their own experiences and their own interpretations. And while a classroom isn’t a consciousness-raising group, part of liberal arts education is insisting that we bring our whole selves to the classroom. In such spaces, learning doesn’t happen as a top down experience, but in all sorts of unforeseen and unforeseeable lateral lines, in conversations that begin in class but continue elsewhere where faculty never hear them.

I am a straight, white, cisgender woman who teaches our college’s introduction to Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies. I am regularly in the position of teaching the fundamentals of queer and trans theory to students who have, in many cases, more first-person experience dealing with the issues we discuss than I do. I routinely offer theoretical language and explanatory categories for LGBTQ+ students’ lives, which can be a delicate dance.

Adrienne Rich

On the one hand, these categories and concepts can be empowering for students. They can learn new tools and vocabulary for understanding and naming things they encounter and live every day. They can discover different language to put to experiences and own them, and say, I always felt that way but I didn’t know there was a word for it. The experience can be a revelation – like when they read Adrienne Rich and discover the language of compulsory heterosexuality, or when they study Sara Ahmed and learn to imagine heteronormativity in terms of physicality, as a source of comfort for some bodies and discomfort for others.

But there is a flip side. Learning new conceptual tools and theoretical languages can be alienating for students, especially when the instructor occupies a different position of power and identity than the students do. Teaching such students can easily come across as suggesting that I know, or this academic field understands, more about your identity and your life than you know yourself. Students can experience this as arrogance and even as an assault on their right to interpret themselves as they wish.

As someone who isn’t LGBTQ+ myself, I navigate these double binds day in and day out. Some days I do better than others. As I work to be a source of support for my students, I find myself asking a series of admittedly unanswerable questions.

***

Here are a few of my questions: How can I bring my self – as a Jew on a largely Christian campus, as a woman in the hostile and overwhelmingly male-dominated field of philosophy – to my students without ever conflating my struggles with theirs? How can I make it clear that my own specific experiences of marginalization inform how I teach – but are not some sort of master key to understanding other forms of marginalization, including the ones that may structure my students’ lives? How can I keep myself from falling into the trap of collapsing “difference” into a catch-all term that can’t possibly carry the weight of all that it is asked to bear? How can I refrain from participating in the interpretive violence that is called into being when we wrestle “difference” into a manageable category that surreptitiously flattens out the genuine differences between human beings and the ways in which they live, suffer, name their experiences and identities and desires?

Every year, I teach the essay “Report from the Bahamas,” in which the poet and activist June Jordan meditates on race, class, and gender while on vacation alone in the Bahamas, narrating a series of connections and misrecognitions with the workers she encounters at the Sheraton British Colonial hotel and with her students back in the States. Jordan reminds her readers that connections based on identity—even, or especially, identity forged through oppression—are not automatic: “When we get the monsters off our backs all of us may want to run in very different directions.” How can I refrain from becoming, unwittingly, one of the monsters in my students’ lives?

Pride Flag

How can I honor – in an absolute, unassailable way – my students’ identities and experiences and desires while nonetheless teaching students that identity is not an immutable category and that experience itself is not unassailable? How can I maintain that honor while contextualizing and historicizing categories that make up aspects of my students’ selfhood and are precious and real and essential to them?

What if, as many theorists I teach suggest, we don’t know ourselves as well as we think we do? What if it is structurally possible for other people to know us in ways we can’t know ourselves, including seeing us more clearly in certain ways than we see ourselves? What if the belief that the most intimate knowledge of the self comes from the self is wrong? What if we aren’t the foremost authorities on ourselves?

How can I honor experiences that are different from my own in an absolute way while not assuming that each individual is the best or most reliable narrator of their own lives? While still acknowledging that they are nonetheless the most important narrators of those lives?

In mulling these questions, it helps me to read and to teach Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, one of the founders of queer theory. Sedgwick says that one of the things that makes the word queer different from other LGBTQ+ identity language is its relation to the speaker. She writes in this connection, “A hypothesis worth making explicit: that there are important senses in which queer can signify only when attached to the first person. One possible corollary: that what it takes – all it takes – to make the description ‘queer’ a true one is the impulsion to use it in the first person.” Sedgwick exposes the gulf between a first and third person perspective and point of enunciation, and her insight helps me, at least, make sense of my own simultaneous authority and absolute lack of it.

At some point, though, when you’re running a classroom, you can’t let questions overwhelm you. Theorizing stops, and you have to make some rules. Here are mine.

1) Believe your students.

I have a sign on my office door that says, “I believe you.” It was designed as part of a campus-wide initiative for survivors of sexual assault to know that I’m a safe person to go to, but I’ve come to think it signifies much more than that. It means I will set aside all my theoretical suppositions about knowledge and authority, and trust that my students know more than I do about what they need, and do my best to understand it.

I have a sign on my office door that says, “I believe you.” It was designed as part of a campus-wide initiative for survivors of sexual assault to know that I’m a safe person to go to, but I’ve come to think it signifies much more than that. It means I will set aside all my theoretical suppositions about knowledge and authority, and trust that my students know more than I do about what they need, and do my best to understand it.

2) Trust students when they tell you about the language they want you to use, full stop.

This might be about pronouns or names or it might be about words that you have never thought about before but your students have and they want you to stop using them, and you should do it right away. This will be humbling, and it will never end, and you will never be perfect, but you don’t have a choice. Besides, for anyone in any position of authority, it’s good practice to be humbled on a regular basis.

Your attachment to particular kinds of language does not outweigh your students’ need for you to stop using it.

3) A corollary: find a way to keep talking anyway, using different language.

4) Find a way to short-circuit any defensiveness that arises when students want you to change your language or your classroom practices.

Understand that students wanting you to change isn’t a referendum on you as a person; it’s about your ability to construct a safe classroom space for your LGBTQ+ students, to create the conditions under which genuine learning becomes possible.

5) Trust students when their desired classroom practices are different from what you’re accustomed to or what you think they need, and ask them from day one about what those practices might be, and then listen.

6) Adopt an attitude of profound epistemic humility.

Ask stupid questions and be willing to be laughed at. Trust that the laughter will be mostly kind-hearted.

7) This is the lesson I feel the shakiest about saying in public, but in some real way, a specifically pedagogical way, you have to love your students. You have to love them in and especially because of their alterity and their singularity and vulnerability and because of your own vulnerability before them, in the knowledge that the classroom is a place where we bare our souls and where all of us, faculty and students both, tell each other more than we know.

And finally, 8) Trust that if you do these things, eventually you will get to do all the problematizing and critique and close reading that you want. But the condition of the possibility of all of these things is safety and trust. And you have to be the one to promise this. And then you have to make good on your promise.

Abby Kluchin is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies and Coordinator of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies at Ursinus College. She is also co-founder and Associate Director At-Large of the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. She is currently working on a book project that interrogates contemporary debates over sexual ethics alongside classic philosophical texts in order to propose an intersubjective theory of consent.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.