Catholic Gothic Horror and the Monsters in Our Midst

The final installment in our three-part series comparing Catholic horror films and novels to actual horrors committed by the Catholic Church

(Image source: Poster for the film The Devil’s Doorway)

About the Catholic Horrors Series: For the past two centuries, Catholicism has played a special role in American horror stories. During that time, the Catholic Church has been complicit in real-life horrors. In this three-part series, three scholars of American Catholicism – Jack Lee Downey, Matthew Cressler, and Kathleen Holscher – consider Catholic horror as a cinematic and literary genre alongside horrors committed by the Catholic Church and its leaders. In so doing, they explore horror as an aesthetic and as a way to analyze and confront the shadow side of Catholicism in North America. Read part one here and part two here.

***

“The gruesome discovery took decades and for some survivors of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada, the confirmation that children as young as 3 were buried on school grounds crystallizes the sorrow they have carried all their lives.” (CNN, June 1, 2021)

“You ever see that hill up close? They cook Indian kids up there for that zombie priest! Normal zombies just eat anyone, but these religiofied zombies, they throw the kids down this hole to the cooker [..]. Why do you think so many kids go missing at St. D’s?” (Rhymes for Young Ghouls, 2013).

“The colonial world, as an offspring of democracy, was not the antithesis of the democratic order. It has always been [..] its nocturnal face.” (Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics)

I.

In October 1968, six months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., a former Catholic school kid from the Bronx premiered a low budget film that changed American horror forever. With its apocalyptic legion of cannibalistic reanimated corpses, George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead redefined the zombie flic. And with its protagonist Ben, a Black man who is murdered by police officers in a case of mistaken-for-a-zombie identity, Night of the Living Dead also became a template for generations of “social thrillers,” including Jordan Peele’s 2017 hit Get Out.

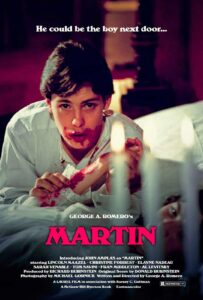

In the lull between Night of the Living Dead and its sequel Dawn of the Dead (1978), George Romero retired to his new hometown of Pittsburgh to make a film about a vampire. While the inspiration for the Night of the Living Dead’s ghouls might have sprung from the director’s Catholic imagination, his 1977 film Martin clearly did so. In Martin, the factories and midcentury-modern houses of Pittsburgh play backdrop for a story about an awkward youth who lives with his devoutly Catholic and ethnically Lithuanian uncle, Tateh Cuda. The young Martin understands himself to be an ancient Nosferatu, or vampire. He drugs and kills women, and drinks their blood. Part of the terror of Martin lies in the quiet sociopathy – and misogyny – of the title character’s acts. But Martin’s terror also comes from Romero’s decision to disrupt the declining industrial landscape of 1970s Pittsburgh with jarring black-and-white sequences and “old world” Catholic motifs to depict Martin’s vampiric memories (or are they only fantasies?). Although Romero is best-known for Night of the Living Dead, the director insisted that Martin was his favorite work.

The Catholic interludes that raise the vital question of Martin. – is he a vampire, or isn’t he? – are classic episodes of gothic horror. “We [..] know the Gothic when we see it,” writes media studies scholar Misha Kavka. In Martin, the gothic appears in dripping candle wax, fog, statues of the Virgin Mary, and in Uncle Cuda’s insistence that his soft-spoken nephew is a demon. “An old person needs a priest who [..] believes in the old ways,” Cuda tells a cleric visiting the family home one evening. “If our priests cannot save us from such things, [..] who can?”

In Martin and other movies, the gothic is a trick of time; it injects an often unspecified but affectively medieval past into the ordinariness of life: both the fictional “here and now” in film and the here-and-now of audiences who watch it. In American film, the Catholic-as-gothic shows up on screen as a courier of “the old ways,” with its weird aesthetics (blood and statues and veiled people), its differently ordered human relations (autocratic clerics and rule-bound nuns), and its porosity between natural and supernatural worlds. If a filmmaker does a good job, like Romero does in Martin, Catholic gothic interpolations sow doubts for film audiences—however half-formed, however nervously laughed off—about things that comprise the realities of our modern world.

In Martin and other movies, the gothic is a trick of time; it injects an often unspecified but affectively medieval past into the ordinariness of life: both the fictional “here and now” in film and the here-and-now of audiences who watch it. In American film, the Catholic-as-gothic shows up on screen as a courier of “the old ways,” with its weird aesthetics (blood and statues and veiled people), its differently ordered human relations (autocratic clerics and rule-bound nuns), and its porosity between natural and supernatural worlds. If a filmmaker does a good job, like Romero does in Martin, Catholic gothic interpolations sow doubts for film audiences—however half-formed, however nervously laughed off—about things that comprise the realities of our modern world.

When horror films go gothic like this, they riff on a way Americans parse time and tell stories about themselves. Americans enjoy stories that affirm their collective “here and now” – their government, their economy, their scientific achievements – by raising the specter of outmoded societies. From The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk (1836) through Black Legend tales that circulated during the Mexican-American and Spanish-American wars, Catholic pasts—as conjured through American storytelling—have played a special role in this work. Set in the “old world” and stalled in the Middle Ages, these Catholic pasts bring hair-raising qualities—including brutality, authoritarianism, and superstition—that make them go-to resources for the “we are not them” and “they are not now” American brand of patriotic storytelling.

In American horror, the Catholic gothic works similarly. It haunts from faraway places and hearkens to bygone times that are stranger and scarier than the United States. Its terror is about its otherness – its spaces are never quite our spaces, its time is never our time, its subjects are never ourselves.

But what if the Catholic gothic haunted from within actual American space and time? What if its horrors were also problems of American history? Films from other parts of the world suggest that Catholicism haunts precisely like this. Both 2018’s The Devil’s Doorway from Ireland and 2013’s Rhymes for Young Ghouls from First Nations-Canada locate the gothic not in old world, pre-modern times, but in Catholic institutions that functioned recently – within the last century – in tandem with modern governments. In these films, the Catholic gothic haunts not as a ghost of difference (or at least not only as that), but to portray gruesome abuses that happened at Catholic-run institutions, and to explore the nature of their atrocities.

II.

The Devil’s Doorway is the debut of writer-director Aislinn Clarke, the first Irish woman to direct a feature-length horror film. The film takes place in 1960. Its setting is an unnamed Magdalene asylum (sometimes called a Magdalene laundry), one of the Catholic institutions that, in real life and with support from the Irish government, housed, confined, and extracted unpaid labor from approximately 10,000 women – including unwed mothers, sex workers, orphans, the mentally disabled, and other “socially unfit” females – across Ireland throughout most of the twentieth century. Employing the found footage technique popularized by horror films like The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Cloverfield (2008), The Devil’s Doorway follows two priests – one with a 16 mm movie camera in tow – who enter the asylum to investigate reports of a miracle.

Once inside the building, Fathers Thomas Riley (an old priest) and John Thorton (a young priest) are confronted with accumulating horrors. Children’s disembodied chatter echoes through the mildewed halls of the asylum at midnight, religious statues hemorrhage blood, and the clerics discover a young, pregnant woman named Kathleen chained in a basement room with a dirt floor. Kathleen is diabolically possessed or psychologically damaged or both. As the asylum consumes the priests – and as they scramble to rescue Kathleen’s newborn – the clerics retreat further into its cellars and become lost in crumbling catacombs strewn with the skeletons of children. The film ends with the elder priest’s last confession, confided to the camera, and the climatic revelation of a “Satanic sanctuary,” deep in the bowels of the Earth. The Catholic sisters who run the asylum tend the Satanic shrine, and through it they have unleashed the demonic forces gripping the place.

(A scene from The Devil’s Doorway)

In The Devil’s Doorway, the gothic, animated by motifs of creaky architecture, ghostly hauntings, and female captivity, exposes viewers to the horrors of an actual twentieth-century Irish Catholic institution. “You send all the country’s dirty secrets here, here to my home,” the asylum’s mother superior snarls to the visiting priests. “Leave us to hide all the messes, and cover it all up. [..] Do you know how many of the babies born here had fathers who were fathers, Father?”

The historical abuses the movie confronts – from the lifelong confinement of women in asylums, to the physical beatings and sexual assaults that happened there – are palpable.

The film’s terror, however, curdles in the space between these human cruelties and the supernatural evil unleashed by the humans who commit them. For most of the movie, the elder Fr. Thomas doubts the asylum’s horrors exceed the work of human beings. “The evil I’ve seen has always been the human kind,” he tells his partner. “There’s no evil in the world that can surpass that done by human hand.” In the film’s final moments, however, Fr. Thomas stands face-to-face with the devil. At last, the magnitude of the asylum’s cruelty renders it incomprehensible, and – so Clarke suggests – the supernatural steps in as its new register.

The Devil’s Doorway self-consciously references American films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Exorcist (1973). Aislinn Clarke was raised Catholic and remembers watching The Exorcist as a seven-year-old alongside her devout father (who was also a horror fan). Like both Martin and The Exorcist, The Devil’s Doorway invokes the “hero priests” that Matthew Cressler describes as central to Catholic horror as a genre. “This is the logic that propels Catholic horror,” Cressler writes, “that the church and its clerics are the only forces with the power to go toe to toe with true Evil.” It feels familiar when, in The Devil’s Doorway, an intergenerational pair of clergy confront the devil. In Clarke’s Irish version of this contest, however, there is no Regan in her prim coat, kissing a priest’s collar at the film’s end. In the depths of the Magdalene asylum, it is the devil who wins the day.

***

The 2013 film Rhymes for Young Ghouls, by Listuguj Mi’gmaq (First Nations) writer-director Jeff Barnaby, draws on similar gothic motifs to depict a Canadian residential school. Like Magdalene asylums in Ireland, residential schools for First Nations children in Canada were predominantly Catholic institutions, managed and staffed by priests and sisters, and supported by the government. Like Magdalene asylums, the historical horrors of these schools—which include the forced removal of at least 150,000 children from their families, as well as endemic emotional, physical, sexual, and cultural abuse – lasted through most of the twentieth century.

While Barnaby has legitimate horror chops (see his 2019 zombie uprising film Blood Quantum), Rhymes for Young Ghouls is less horror flick and more residential school revenge fantasy. The film is set in 1976 on the fictional Red Crow Mi’kmaq Reserve, and its plot moves between the gothic tropes of St. Dymphna’s school, perched castle-like upon a nearby hill, and the drug addiction, imprisonment, and suicide wrought on the Mi’kmaq people living on the reservation below.

The film is “highly stylized with a dystopian tint,” and its protagonist Aila (played by Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs of Reservation Dogs) is a survivor but not a hero. Aila lost her mother to suicide and her father to prison. She sells drugs to fund bribe payments to the local Indian agent, Popper, that keep her out of St. Dymphna’s. When her scheme fails though, Aila is abducted and brought to the institution. A pair of nuns strip her naked. A priest shears her hair. Aila finds herself imprisoned in an underground cell (“the darkest deepest hole we’ve got,” Popper taunts her).

Unlike children who disappeared into St. Dymphna’s before her, however, Aila escapes, and back on the outside, she plots revenge. Outfitted in Halloween masks—including one in the likeness of a plague doctor—Aila and her friends sneak back into St. Dymphna’s at night. Like the priests in The Devils Doorway, the youth make their way through shadowy passages and descend to the dank recesses of the building’s basement. Rather than succumb to St. Dymphna’s evil, however, the kids use its subterranean chambers to exact their retribution. They pour feces into the building’s ancient pipes, and Popper gets a sickening surprise as he showers on a floor above.

(A scene from Rhymes for Young Ghouls)

Like The Devil’s Doorway, Rhymes for Young Ghouls relishes the gothic; both films lead viewers down spiral staircases and through underground tunnels, both include girls in dark cells, both depict the following-orders cruelty of Catholic nuns. And like The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, published nearly two centuries earlier, both give viewers earthen tombs strewn with the remains of children. As Aila sleeps in her cell, she dreams of the nearby cemetery, where her mother is buried in an unmarked grave. She watches the ground of the cemetery rupture to expose a yawning pit, filled with small bodies. “I wonder how many ghosts wander around down in this hole,” Aila narrates. “How the devil doesn’t let them go. Or how many got out that were ruined all the same.”

Beyond these similarities, however, the films diverge sharply. While the horrors of the Magdalene asylum destroy Fathers Thomas and John, Jeff Barnaby conjures St. Dymphna’s horrors in the service of imagining what it looks like for First Nations youth to survive on the other side of monstrosity. St. Dymphna’s is scary, yes, but its frayed seams also show. Its gothic verges on caricature; if it haunts residents of the reserve in 1976, it does so like a ghost who doesn’t know it is dead. And Aila is already over it, even as it tries to ruin her. She wears a gas mask throughout the film, both while she sits on couches in trailers dense with marijuana smoke, and while she raids St. Dymphna’s. “She’s gonna be eating people after the apocalypse,” Aila’s uncle muses.

III.

Both Jeff Barnaby and Aislinn Clarke use the gothic to show how the past haunts the present. But unlike Martin and other American horror films, Rhymes for Young Ghouls and The Devil’s Doorway conjure pasts that are still close-at-hand—that carry stories not of medieval terrors, but of twentieth century institutions that did gruesome things in consort with contemporary governments. The power of their unnerving subjects to haunt comes not only, or even mainly, from their strangeness. Rather, it extends from the trauma those subjects unleashed near to home, and the intergenerational scars their survivors carry.

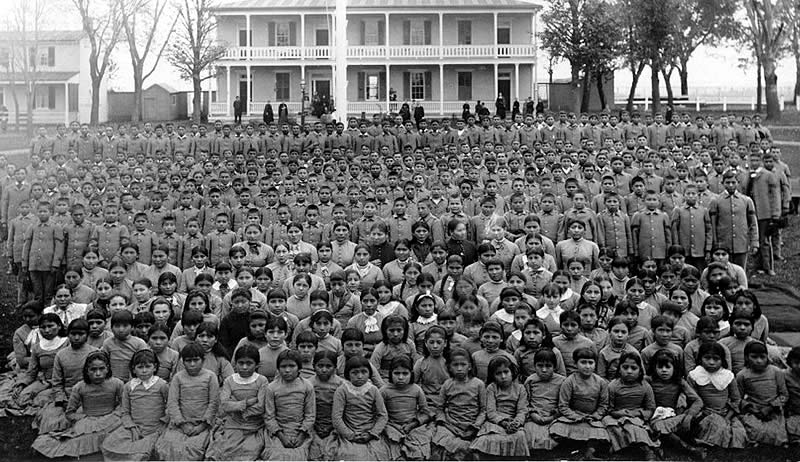

Here in the United States, many types of Catholic institutions, including hospitals, orphanages, and schools, operated in the twentieth century with support from the government, and many performed work that aligned with state interests. Like their counterparts in Ireland and Canada, some of these American Catholic institutions had monstrous underbellies. For example, a U.S. order of Catholic women religious called the Sisters of the Good Shepherd ran “reformation houses.” These houses functioned as part of a “bifurcated system,” alongside women’s prisons, and involuntarily housed residents convicted by U.S. courts of sexual misconduct. We also know that Catholic religious orders ran dozens of U.S. boarding schools for Native children, partly funded by the federal government, and that abuse was rampant in those schools.

(American Indian boarding school. Image source: Wikipedia)

We need look no further than survivor accounts from American Indian boarding schools to find the gothic at work in the real and modern world. Barbara Charbonneau-Dahlen, a woman from the Yankton Sioux reservation who attended St. Paul’s Catholic boarding school during the 1950s, remembers a priest forcing her to perform oral sex in the basement of the church. “He would lift me up and set me in the coffins,” Charbonneau-Dahlen told a reporter. “It would always be, ‘if you ever tell, I’ll put you in here.’” Another abuse survivor at St. Paul’s recalls being beaten and stripped by nuns, and locked in an attic. A third describes being thrown down a “laundry chute, stuffed in a trash can and locked in an incinerator” for not speaking English.

Here in the United States gothic horror also exceeds Catholicism. Neither women’s prisons nor Native boarding schools are exclusively religious projects, and these institutions are also full of non-Catholic brutality. In the recently published first volume of its Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, the U.S. Department of the Interior identified more than four hundred federal Indian boarding schools, and noted that they regularly inflicted corporal punishments, including “withholding food; whipping; slapping; and cuffing.” The Department’s investigation has also begun identifying burial sites at those schools. These government-run institutions exude the gothic; they captured children and buried them in unmarked graves too.

***

“Catholicism has proven and enduring wellspring of dread in American culture,” Jack Lee Downey reminds us. The catch is that, too often, Catholicism’s threats of authoritarianism, captivity, and blood – as well as its open channels to the supernatural – have been presented in U.S. culture as episodes of dreadful difference, as shadowy places we peek into with bated breath, and from which we exit into daylight, relieved they are not our own. At their best, these invocations of Catholicism leave us uneasy, haunted by new nightmares about what might dwell under the surface of things we know. But here is the rub: the Catholic gothic is already among us, a monster in our midst, embedded in American space and American time. This is a matter of history and not simply nightmarish wondering.

Kathleen Holscher is associate professor of religious studies and American studies, and holds the endowed chair in Roman Catholic studies, at the University of New Mexico. Among her other publications, she is the author of the Revealer article “Priests That Moved: Catholicism, Colonized Peoples, and Sex Abuse in the U.S. Southwest.”